|

|

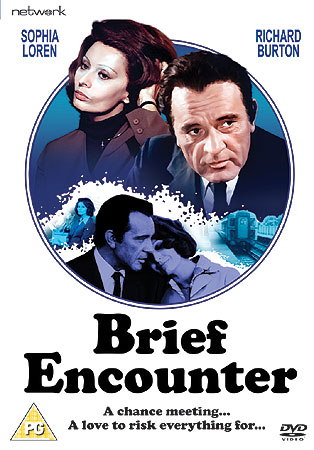

Brief Encounter

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (22nd June 2009). |

|

The Film

Produced almost thirty years after David Lean and Noel Coward’s now classic film Brief Encounter (1945), this 1974 made-for-television remake may at first glance appear to be entirely redundant, doomed to stand in the shadow of Lean’s celebrated picture. However, thanks to the input of director Alan Bridges and screenwriter John Bowen this remake is not entirely without merit, and despite a very ‘flat’ television movie aesthetic (dominated by the use of the economical two-shot) this reworking of Lean’s picture adds some interesting new ‘twists’ to the narrative of the original film.

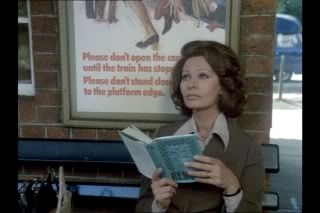

The remake opens with Sophia Loren sitting on a train platform. Loren plays Anna Jesson, who regularly commutes via train into Winchester; through chance Jesson meets fellow commuter Alec Harvey (Richard Burton). Her eye irritated by some grit that is blown into it by a passing train, Jesson seeks solace in the cafeteria of the train station, and seeing Jesson’s distress Harvey helps remove the dust from her eye. Following her encounter with Harvey, Jesson travels home; via a series of brief scenes, her marriage to husband Graham (Jack Hedley), a solicitor, is revealed to the audience. Anna and Graham Jesson have two sons, Alistair (Benjamin Edney) and Dominic (Madeleine Hinde). Jesson and Harvey meet again by chance, in a park in Winchester: Harvey tells Jesson that he is a doctor who lives in Basingstoke but visits Winchester once a week, in order to tend to his patients at the chest clinic. Over lunch in a cafeteria, Jesson informs Harvey that she has lived in England for seventeen years, and that her family in Italy died during the Second World War. Jesson confesses that she met her husband ‘at a time when I was very lonely’. Their conversation is ominously interrupted by the roar of a train as it passes through the station. Anna and Alec’s friendship deepens. When, during a visit to an outdoor mystery play in Winchester, Anna asks Alec if he feels ‘guilty at all’, Alec declares, ‘What’s wrong with a little relaxation? What on earth do you feel guilty about?’ Slowly, Alec and Anna seem to fall in love; ‘We’re in love with each other, you know that […] Whether it goes any further, whether we ever get together, we’re lovers’, Alec declares. In this remake, the focus is largely on Anna Jesson; the film is almost completely focalised through Anna’s perspective, with only a handful of scenes showing Alec on his own. In fact, where Anna’s relationship with her husband Graham and their two sons takes up the majority of the film’s running time, the first glimpse of Alec’s home life takes place more than an hour into the film; played by Burton as a downtrodden and very serious man, Alec’s relationship with his wife Melanie (Ann Firbank) is remote, but his wife is very practical about their relationship – ‘Being in love is not a state that goes on. How could it?’

This remake of Brief Encounter was written by John Bowen, who during his long career as a television screenwriter wrote one of strongest stories within Thames’ Armchair Thriller series, the 1978 six-part adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel A Dog’s Ransom. Bowen also delivered the 1973 adaptation of M. R. James’ ‘The Treasure of Abbott Thomas’ for the BBC’s long-running A Ghost Story for Christmas strand, as well as several scripts for LWT’s 1971 dystopic science fiction series The Guardians. Bowen’s reworking of Brief Encounter makes some interesting deviations from the original material. Where the original film is often seen as a picture about ‘Englishness’ (for example, see Cook, 2005: 104), the decision in this remake to give the character of Anna a different cultural background (most likely dictated by the casting of Sophia Loren, wife of the film’s producer, Carlo Ponti) shifts the focus of this remake slightly: rather than focusing on the sexual repression of the English middle class (as represented in the original film by Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard), this remake focuses on the cultural differences between the Italian-born Anna and the very English Alec. Of Anna, Alec observes that ‘You say you try to be very English; you don’t seem to be very English to me’. Likewise, in the same conversation, Anna uses a series of cultural stereotypes to reflect on the qualities of her English husband Graham: ‘He’s very tall, very kind, not emotional; and he’s very intelligent’. Perhaps surprisingly, Anna’s home life is shown as anything other than stifling, characterised simply by her lack of ability to engage with her husband and sons Dominic and Alistair. A loving husband, Graham is shown as a caring father who has a strong relationship with both Dominic and Alistair. However, Anna is on the periphery of the relationship between the three male members of the household, seemingly unable to communicate with them: where Graham is shown playing with his sons, engaging them in bouts of Monopoly and games in the garden at the rear of the Jesson house, Anna’s relationship with her sons is more clumsy. Many scenes show Anna watching Graham, Dominic and Alistair from a distance, and her attempts to engage with her family tend to fail – seemingly largely due to her sense of cultural ‘otherness’. In one scene, Anna is shown watching Graham in the garden, who as he is working chats with Dominic and Alistair. Told by her housekeeper Ilsa that the family’s supper is ready, Anna takes the opportunity to go outside and engage with her sons. Playfully grabbing hold of Alistair as he runs to the house, Anna accidentally knocks him to the ground and appears unsure of how to react; Alistair simply picks himself up and declares, ‘I’m alright’. Throughout the film, Anna seems uncertain of how to relate to Graham, Alistair and Dominic – not out of a lack of emotion but simply because she is a cultural outsider.

Perhaps the key to Anna and Graham’s relationship is suggested in a scene in which Graham enlists the help of Anna in completing a crossword puzzle; Anna provides the answer to a question which uses as its basis a quote from the poet George Herbert, ‘Love bade me welcome but my soul drew back’. In the same scene, Anna takes offence at Graham’s suggestion that she is ‘analytical’: ‘Analytical. It makes me sound cold. I don’t like that: I’m not cold’, she asserts angrily. However, Graham is a loving husband who, in one scene, tucks the children in bed before going to his and Anna’s bedroom, where he and Anna – in a scene shot self-consciously through the doorframe, which acts as a frame within the film frame – kiss passionately. By contrast, Anna’s relationship with Alec is curiously flat and uninspiring, characterised by an almost complete lack of physical intimacy. During a visit to a riverbank, Alec tells Anna, ‘You know what’s happened, don’t you? [….] We’ve fallen in love’. However, during this moment both Alec and Anna are standing apart; even when, later in the scene, Alec takes Anna’s hand there is considerable physical distance between the two characters.

Director Alan Bridges was a veteran of the television industry who by the early 1970s had worked on a number of features, including the 1966 science fiction film Invasion. However, Bridges is mostly known for his association with crime pictures, thanks to his work for Merton Park Studios’ ‘B’ feature series The Edgar Wallace Mysteries (1960-5). (The films in this series were screened on US television, in versions edited to under an hour in length, under the title The Edgar Wallace Mystery Theatre.) In the 1970s, Bridges’ work began to develop away from the restrictive confines of the genres of science fiction and crime, and in the 1980s Bridges found himself working on films within the tradition of ‘quality’ British filmmaking, such as The Shooting Party (1985). Set just before the outbreak of the First World War, The Shooting Party at first glance appears to be a nostalgic ‘heritage’ film in the tradition of the then-popular Merchant Ivory pictures, but on closer inspection offers an ironic critique of the class-riddled attitudes of the Edwardian era. According to Contemporary British and Irish Film Directors, Bridges’ work ‘frequently moved between those dominant paradigms of British cinema, realism and the “quality” tradition’ (Shail, 2001: 42). Thanks to its association with both Noel Coward and David Lean, the original Brief Encounter is an iconic film within British cinema’s ‘quality’ tradition. In the context of Bridges’ career, this remake of David Lean’s highly-regarded classic is sandwiched by a couple of features that focus on similar themes: principally the threat of adultery, forbidden desire and repressed love affairs. Brief Encounter was produced a year after Bridges’ ‘most notable critical success’, The Hireling – winner of the 1973 Palme d’Or (ibid.). Adapted from a novel by L. P. Hartley, The Hireling focuses on the theme of repression and taboo love, with its narrative revolving around a forbidden affair between Lady Franklin (Sarah Miles) and Steven Ledbetter (Robert Shaw), a lowly chauffeur. In 1975, Bridges returned to similar thematic territory with the film Out of Season, which finds Joe Tanner (Cliff Robertson) visiting an English seaside resort, where he rekindles an old affair with the owner of a local hotel, Ann (Vanessa Redgrave). The relationship between Ann and Joe becomes even more complicated when Ann’s daughter Joanna (Susan George) also begins a romance with Tanner; it is suggested that Joanna’s affair with Tanner is motivated by Joanna’s desire to spite her mother. However, there is more than a hint of suggestion that, unknown to Tanner, Joanna is in fact the fruit of Tanner and Ann’s earlier forbidden love affair. For his exploration of these themes, Bridges’ work has been cited as possessing a ‘fascination with varying forms of social unease’ and a ‘continuing fascination with the repressive nature of class and the anxieties caused by a submerged sexuality’ (ibid.).

Taken on its own terms, this rethinking of Brief Encounter is interesting in the way that is shifts its focus from the issue of ‘Englishness’ onto the cultural conflict between the Italian Anna and both her husband Graham and her lover Alec, both of whom are stereotypically English. The film is even more interesting when seen as part of a triptych of mid-1970s films that Alan Bridges made about forbidden desires and repressed sexuality, although this film is far less intense than Bridges’ later Out of Season – a film sorely in need of a DVD release. The film runs for 99:11 mins (PAL). Reputedly shown on American television in an abbreviated version, this DVD represents the full-length edit of the film.

Video

Presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1, this remake of Brief Encounter looks very good indeed: colours are rich and vibrant, and the image on this DVD release is very detailed.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track, which is clear and expansive. The film makes very good use of an effective 1970s-era score by Cyril Ornadel. There are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole extra is an image gallery (2:15).

Overall

Whilst not comparable in quality to David Lean’s original film, this remake by Alan Bridges is not without its interesting qualities. The theme of cultural conflict, as exhibited in the relationships between Anna and Graham and between Anna and Alec, is an interesting and valuable addition to the material, shifting the focus of the narrative slightly and ensuring that this remake of David Lean’s 1945 picture has enough unique qualities to make it worth watching – it isn’t simply a retread of the original film. However, for best results, it’s worth watching this film alongside Alan Bridges’ other mid-1970s pictures The Hireling and Out of Season, to see the development of Bridges’ preoccupation with the theme of taboo desires. All said and done, this remake of Brief Encounter is nowhere near as bad as its reputation might suggest, and this DVD contains a handsome presentation of this made-for-television production. References: Cook, Pam, 2005: Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in British Cinema. London: Routledge Shail, Robert, 2001: ‘Alan Bridges’. In: Cullen, Del & Patterson, Hannah (eds), 2001: Contemporary British and Irish Film Directors. Manchester: Wallflower Press For more information, please visit the homepage of .

|

|||||

|