|

|

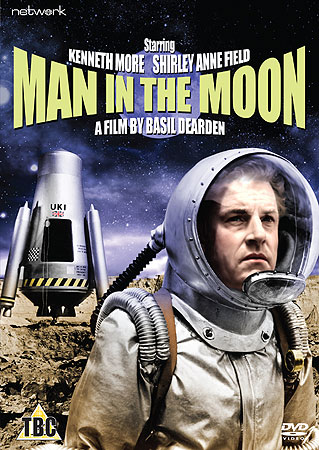

Man in the Moon (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th July 2009). |

|

The Film

During the 1940s and 1950s, the director Basil Dearden became closely associated with the post-war ‘social problem’ film, a movement in British cinema that examined social issues through the gaze of the genre of crime fiction. Many of the films Dearden made during this period were produced by Dearden and Michael Relph. Dearden and Relph worked together for over twenty years: the two men’s partnership began during the Second World War, when Dearden and Relph were brought together by the Ministry of Information to make The Bells Go Down (1943), a propaganda film focusing on the effects of the Blitz on a community in London’s East End. In the mid-1940s, Dearden and Relph collaborated on several films for Ealing Studios. During the post-war period, the pair increasingly focused on making films that examined the cracks underlying the ‘consensus politics’ that followed the Second World War: the films Dearden and Relph made during this period evidence a commitment to realism and a focus on the tensions between communities and those classed as ‘outsiders’. Frieda (Dearden, 1947) focused on the struggles faced by a young German woman (Glynis Johns), the wife of an RAF pilot (David Farrar), when she moves with her husband to an English village; both The Blue Lamp (Dearden, 1950) and Violent Playground (Dearden, 1958) examined the tensions placed on communities by the appearance of youth crime in 1940s and 1950s Britain; Sapphire (Dearden, 1959) focuses on racial prejudice against the backdrop of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots. Dearden carried this tradition of the ‘social problem’ film into the 1960s: his 1961 picture Victim examines the persecution of homosexuals through the framework of a narrative that focuses on the blackmailing of a young gay solicitor (played by Dirk Bogarde).

This 1960 collaboration between Relph and Dearden is an altogether different beast: an eccentric science-fiction comedy, The Man in the Moon stars Kenneth More. as William Blood. The film opens with a bizarre image: a hospital bed in the middle of the English countryside. The occupant of the bed pulls back the covers, revealing himself to be William Blood. Blood takes in the countryside, watching the animals – a squirrel drops its acorn on him from a tree – until a beautiful woman (Shirley Anne Field) in an evening dress approaches but is startled and runs away. A vehicle from the Ministry of Health arrives. Blood is a guinea pig for the Common Cold Research Centre. The scientists complain that they ‘don’t get any results: it’s not healthy for someone to be as healthy as you are’. Soon, Blood is approached by NARSTI, the National Atomic Research Station and Technological Institute. NARSTI want Blood to be the first man on the moon, spearheading an expedition by NARSTI’s ‘proper’ astronauts: the scientists at NARSTI assert that, ‘It was decided that because of public opinion, we wouldn’t risk sending an animal [into space] again. So we have been looking for a human substitute’.

Although on the surface wildly different from Dearden and Relph’s ‘social problem’ films, The Man in the Moon still has its finger on the proverbial cultural pulse. The film satirises the institutionalisation and corporatisation of science and technology: NARSTI’s headquarters is a modernist building dominated by glass and contemporary furniture, something like the scientific institutes in the Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg’s science-fiction nightmares (for example, Biocarbon Alamgamate in Scanners, 1981, or The Somafree Institute in The Brood, 1979). The scientists in charge of the experiment to send Blood into space – Davidson (Michael Horden), Stephens (John Phillips) and Wilmot (John Glyn-Jones) – are clearly working within the framework of government bureaucracy, conducting their research with government money and aware of both public and political opinion: in their first conversation about Blood’s role, they are keen to establish that their new employee is ‘politically neutral’. The scientists, who are rarely seen outside their offices, also have a tiered view of society, at one point Wilmot declares, ‘Terrible thing, truth – particularly if the wrong people get hold of it’. They are keen to get results and show little regard for the dangers that Blood might face: when challenged by the other astronauts about Blood’s role, Wilmot states that Blood is ‘ordinary in the sense that he’s expendable’. In contrast with them, Blood is a warm, human presence, seeing the experiments largely as a source of childish fun and taking delight in the simple pleasures of life: the film’s opening scene finds him enjoying his stay in the countryside, accompanied by his Thermos flask and a newspaper.

The film thus offers an amusing critique of institutions and bureaucracy, a trend within British cinema that Sarah Street (1997) identifies as one of the defining traits of British film comedies of the 1950s, from the Doctor films (beginning with Doctor in the House; Ralph Thomas, 1954) and the Carry On pictures, which parody institutions from schools to the police force (70). As Street notes, many of the British comedies of this era evidence ‘fears about state power and a mistrust of bureaucratic structures in general’, alongside an ongoing preoccupation with the issue of social class (ibid.: 64) – represented in The Man in the Moon through the class-based conflict between Blood and the scientists.

The film runs for 94:34 mins (PAL) and appears to be uncut.

Video

The film is presented in a screen ratio of 4:3. It’s difficult to ascertain if this is the film’s original screen ratio. However, there seems to be some evidence of cropping: for example, the tilt down the sign outside NARSTI’s headquarters suffers from some fairly damaging cropping on the right-hand side of the frame, making the text on the sign barely legible.

Aside from this, the monochrome image is crisp and detailed.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is clear, but there are no accompanying subtitles.

Extras

The DVD contains some contextual material: - an image gallery (2:25); - a portrait image gallery (1:13); - a behind-the-scenes image gallery (3:10).

Packaging

Unset

Overall

UnsetAn eccentric and warm comedy, The Man in the Moon successfully lampoons petty bureaucracy and government institutions. To a large extent, the film’s success in this regard is thanks to Kenneth More’s warm performance as Blood, who provides a very human counterpoint to the cold rationalism of the scientific institutions in which he is placed. This DVD contains a good presentation of the film, although the image seems to suffer from some cropping (as noted above). However, this is to be forgiven considering the film’s rarity on home video. As such, this DVD represents a very worthwhile purchase for fans of More or Dearden, or for admirers of British comedy in general. References Street, Sarah, 1997: British National Cinema. London: Routledge For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|