|

|

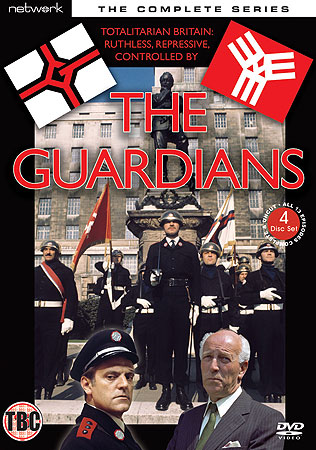

Guardians (TV) (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (1st February 2010). |

|

The Film

The Guardians (LWT, 1971)

Never repeated since its original transmission in 1971, the dystopic science-fiction series The Guardians (LWT, 1971) ran for a single series of thirteen episodes. The series was created by Rex Firkin and Vincent Tilsely; and in its vision of a totalitarian society that allows little room for individualism or free will, The Guardians has some elements in common with The Prisoner (ITC, 1967-8), for which Vincent Tilsley wrote a number of episodes. The Guardians managed to draw upon a number of issues that came to dominate the 1970s (industrial unrest, unemployment, inflation, political violence) but, in the current economic climate, the series also seems strangely timely. At the time of its original broadcast, The Guardians may have appeared to be too closely allegorical of the situation in Northern Ireland and the explosion of political violence that took place in the 1970s, including the Falls Curfew of July 1970 (which is often cited as a major catalyst in Belfast’s Catholic population’s distrust of the British Army). The Guardians depicts a society controlled by the Guardians of the Realm (known simply as ‘The Guardians’ or, more informally, ‘The Gs’) – an unelected police force whose power exceeds that of the politicians and who are presented in the opening credits as similar to an invading army – and their opposition, the loosely-organised ‘Quarmbys’, whose activities mirror those of paramilitary organizations such as the Provisional IRA. (In the episode ‘Appearances’, a group of Quarmbys go so far as to bomb one of the headquarters of the Guardians.) It is likely that these parallels with the Troubles were the reason why The Guardians was never screened in Northern Ireland. However, in truth the conflict between the Guardians and the Quarmbys could be said to parallel much of the political violence that opened the 1970s, from the activities of the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse) in Italy to the Red Army Faction/Baader-Meinhof Group (Rote Armee Faktion) in Germany.

The conflict between the Guardians and the Quarmbys also seems to allude to the conventions of dramas that use as their basis the conflicts between the French resistance and the Nazi occupiers of France during the Second World War; it is probably worth noting that both Tilsley and Firkin had been involved in the production of Manhunt (LWT, 1969), a complex series set in occupied France. The titles sequence to The Guardians certainly depicts the Guardians parading through the streets of London in imagery that seems to allude to the opening sequence of Jean-Pierre Melville’s film about the French resistance, L’armée des ombres (Army of Shadows, 1969), which opens with striking shots of German troops marching along the Champs-Elysées. Each episode opens with the screen divided into nine panels. In the eight panels around the edges of the screen is a montage of images: two flags, both vaguely referential to the Nazi swastika flag (due to its angular design and its use of red, white and black). The panel in the centre of the screen depicts a shot of marching feet: images of marching feet have become metonymic of aggression and totalitarianism thanks to their use in the Odessa Steps sequence of Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1918), just prior to the moment when the Czarist soldiers open fire on the protesting civilians, and Leni Riefenstahl’s Nazi propaganda documentary Triumph des Willens (Triumph of the Will, 1935). This is followed by a mid-shot of a group of the Guardians marching through London whilst holding the flags depicted in the surrounding panels. The men’s uniforms are black, appearing almost like the uniforms of the SS, and their helmets are vaguely futuristic (but resemble the helmets of modern riot police). The music (by Wilfred Josephs) that accompanies this titles sequence is initially sombre and dominated by brass instruments, but it eventually segues into a percussion and brass-dominated militaristic march which is both aggressive and slightly farcical. A title card that begins each episode declares ‘England soon?’, although in the episode ‘The Dirtiest Man in the World’ we are told that the events depicted in the series take place during the 1980s.

In The Entertainment Functions of Television (1980), Percy Tannenbaum refers to The Guardians as ‘the rather brutal Orwellian-type series shown late at night’ (84). Whilst it is true that the series evidences outbursts of brutality (as in the aforementioned episode ‘Appearances’, which ends with the Guardians shooting two Quarmbys before a third takes her own life), The Guardians is also thoughtful and very well-crafted but perhaps a little too ‘talky’ for some, and there are a couple of episodes (notably, episode two, ‘Pursuit’) which appear to be ‘treading water’: in fact, it could be argued that after a strong first episode, the series only seems to regain its momentum at around episode four or five. Tannenbaum’s description of The Guardians as ‘Orwellian’ is more apt, as the series takes from Orwell’s novel 1984 (1948) the achievement of totalitarianism by what the American political commentator Walter Lippmann referred to as the ‘manufacture of consent’ (in his 1922 book Public Opinion): like in 1984, it’s clear that in the world of The Guardians the powers-that-be use the medium of television as a tool for spreading misinformation and propaganda. To this end, The Guardians also contains brief visions of what series such as Coronation Street or children’s programming may become in a society such as that ruled by ‘the Gs’.

From its first episode, 'The State of England', The Guardians establishes the authorities’ use of television as a means of spreading propraganda and, to use modern parlance, 'spin'. Following the Guardians' breaking-up of a pro-democracy march (in which the Guardians are led by Sergeant Tom Weston, played by John Collin), the Prime Minister, Sir Timothy Hobson (Cyril Luckham), appears on television and suggests that the protesters were mistaken in the general premise underlying the march – that the government was planning to outlaw the right to strike. Hobson’s broadcast rails against 'the subversives of both left and right', with Hobson suggesting that inflation has been stopped 'but we've scarcely begun to repair the damage which that inflation caused before we came to office'. The broadcast refers to 'our new prosperity' but suggests that there is also the existence of 'real poverty' in British society, and Hobson declares that 'all state pensions and all social security benefits will, with one exception, be doubled': no benefits 'will be paid to strikers, or to the families of strikers [….] [E]very worker will continue to have the legal right to strike, but no longer at the expense of the community. He must now pay for it out of his own pocket. Now, if anyone can call such a measure “fascist”, rather than arising from simple logic and, indeed, simple Christianity, I suggest he considers very carefully whether England is the country he should be living in [….] I hope he will join with us in our march towards a more happier, a more prosperous, a more law-abiding, a more secure, and yes, an even greater England'. Watching the broadcast on his television at home, Weston quotes this last sentence as it appears on the screen, signifying his familiarity with it, and then declares to his wife Clare (Gwyneth Powell) that, 'I don't know whether he's the most saintly man in England, or the biggest liar, or both'. Throughout the series, it is clear that the apparently media savvy government have been using the television as a means of social engineering, and that their sound bites are familiar to the populace. The episode ‘This is Quarmby’ depicts the panic that takes place once the Quarmbys seize the ability to interrupt the government’s broadcasts.

In their attempts to defuse any attempts at a coup, the authorities also deploy another familiar strategy, labeling any dissidents as ‘communists’. In the aforementioned opening sequence to the first episode, the Guardians accuse the protesters of being communists; in response, the shop steward (Windsor Davies) angrily asserts to Weston that, 'If they keep putting uniforms on rotters like you, I'll bloody well become a communist'. By labeling anybody opposing their policies as a communist, the authorities use a form of reductive ‘straw man’ argument that allows them to keep a cap on any possible dissent: in fact, the witch-hunt against communists was, it is suggested, responsible for the creation of the Guardians – Weston later tells a potential colleague that the Guardians were created because ‘communists’ were infiltrating the regular army. Later episodes introduce ‘rehabilitation centres’ which have been created to detain those labeled as communists. The inmates of these rehabilitation centres are kept for an indefinite amount of time, and a number of methods are used to ‘re-educate’ them. In the meantime, they are fed cannabis in order to pacify them. Tom Weston disappears, eventually resurfacing in episode six, ‘Appearance’, in which Clare discovers that he has been identified as a subversive and relocated to one of the new rehabilitation centres. There, Tom is manipulated by two scientists, Dr Thorn (Dinsdale Landen) and Dr Banks (Richard Moore). Thorn and Banks attempt to break Tom’s will, which will allow them to ‘rebuild his personality our way’. In order to induce a breakdown in Tom, Thorn and Banks needle the inmate about his relationship with his wife, telling him that in Tom's absence Clare has begun an affair with the Prime Minister’s son, Chris Hobson (Edward Petheridge). At one point, Tom defiantly asks Thorn ‘What’s wrong with me?’ ‘It used to be called communism’, Thorn replies. ‘Well, what do you call it?’, Tom asks. ‘Neurosis, paranoia, psychosis, schizophrenia’, Thorn tells him.

The Prime Minister himself is conflicted about the role of the Guardians; and it seems that the Guardians’ power has exceeded that of his government. The Guardians are headed by a mysterious figure known as the General, and their representative in parliament is a man named Mr Norman (Derek Smith); Hobson’s conversations with Norman reveal Hobson’s questioning of the Guardians’ level of control. In the first episode, Norman reveals to Hobson that the Guardians have seized Britain’s stockpile of nuclear weapons and moved them to a hidden location. It is at this point that Hobson seems to realise that he is powerless to do anything about the Guardians, and that it is the Guardians who really run the country. In the second episode, ‘Pursuit’, Hobson declares that the Guardians have become ‘too powerful’, and in ‘Head of State’ he proposes to dissolve the Guardians, asserting that most of its members will be ‘absorbed’ into the military and the police. However, Hobson finds that this results in Norman subtly threatening his life and the Guardians arresting Hobson’s son Chris.

The ambivalence of the government towards the Guardians and their methods is matched by their ambivalence towards the concept of democracy. In ‘Head of State’, the Home Secretary Geoffrey Hollis (Peter Howell) reminds Hobson that ‘We’re not a democratic government, not anymore; but we look as if we might be, and that’s reassuring’. Later in the series, in ‘The Logical Approach’, Hobson suggests that 'People often resist what is good for them at first. Later on, they see the good and accept it'. In ‘Appearances’, Hobson’s son Chris tells Clare Weston that although he sympathises with the resistance and dislikes the strict censorship that has been applied to the British media (he tells Clare that ‘I get the facts about England in French and German, and from the Paris edition of the Herald Tribune. The Americans are taking a very pompous line, regarding themselves as the last bastion of democracy. That's a laugh. Look at them, with their riots. Every summer it's a mass murder, and they have to make some great gesture in outer space to bring back world opinion’), he believes that ‘sometimes I think that my father has a point: democracy leads to moral chaos'. Later in the same episode, he returns from visiting various parts of the country and asserts to Clare, 'Do you know what I've discovered? Not only do people need to be told what to do, but they actually enjoy it. Stand there, sign here, do this. As long as everything's arranged for them, there's no anxiety. All over the country, people are willing to obey because it's easier to'. It seems that the Guardians have achieved absolute power through winning the consent of the populace; in a moment that parallels a number of recent debates, Benedict discusses the introduction of identity cards and the storing of individuals’ personal details on centralised computer systems: 'Identity cards we've got already’, he declares to Hobson, ‘and you're right: most people don't mind them because what harm are they? And it's useful to be able to prove your identity and your blood group in case of an accident, and a great deal more medical information; all of it, incidentally, stored away in computers. So, when the government decide that those who are “genetically dangerous” should be sterilised, the computers will already have the information'. In the same exchange, Hobson tellingly asserts to Benedict that ‘Government depends on the consent of the governed’. ‘However obtained’, Benedict adds. ‘By persuasion, example or force, yes’, Hobson responds. However, as Benefict notes, ‘In a democracy, we can always change our bad masters for worse’.

The Quarmbys are not presented as unambiguous heroes either. In ‘Quarmby’, the wife of psychiatrist Tim Benedict (David Burke) hires an inquiry agent, Wilf Benton (David Cook), to follow her husband: she suspects him of an affair. However, Benedict is a member of the Quarmbys, and he also has links with the Guardians. Benton finds out about Benedict’s association with the Quarmbys, and Benedict makes the decision to kill the pitiful private eye. Benedict’s murder of Benton (by breaking his neck) shows that the resistance are as capable of malicious violence as the Guardians themselves. After Benton has been killed, Benedict’s wife Eleanor (Lynn Farley) asks Benedict ‘Why?’ When Benedict weakly asserts, ‘If I said for England [….] for democracy, for freedom’, Eleanor tells him ‘It doesn’t mean anything’. In another plotline that highlights the darker side of the Quarmby's campaign against the Gs, in ‘The Logical Approach’ the Quarmbys recruit Sam Wilson (Ken Jones), whose son has recently been publicly executed by the Guardians. Wilson is used as a patsy: he is ordered to kill the Home Secretary and then shot by another member of the Quarmbys. Wilson’s death effectively makes him a martyr, but his betrayal by the Quarmbys calls into question the Quarmbys’ methods.

Benedict and other members of the Quarmbys seem to be aware of their own motives, and are themselves conflicted about the role that the organisation plays. In ‘Quarmby’, Benedict acknowledges that he is ambivalent about his association with the resistance due to an awareness of his own reasons for being involved in it: 'I know that there's a little boy inside me that just enjoys breaking things up', he tells Eleanor.

Disc One: 1. 'The State of England' (52:13) 2. 'Pursuit' (48:36) 3. 'Head of State' (52:14) Image Gallery (2:39) Disc Two: 4. 'The Logical Approach' (51:58) 5. 'Quarmby' (52:08) 6. 'Appearance' (52:03) Disc Three: 7. 'This is Quarmby' (50:18) 8. 'The Dirtiest Man in the World' (52:41) 9. 'I Want You to Understand Me' Disc Four: 10. ‘The Nature of the Beast’ (53:17) 11. ‘The Roman Empire’ (51:32) 12. ‘The Killing Trade’ (49:46) 13. ‘End in Dust’ (51:21)

Video

Mostly shot on videotape in a studio environment, The Guardians also features some filmed inserts shot on location, using 16mm film. The series looks consistently good, but as with most shows recorded on a combination of VT and film, there is a disjuncture between the visual style of the VT-shot footage (with its flared highlights) and the more gritty aesthetic of the shot-on-film location work (the sequence in which the Guardians chase the Quarmbys, in ‘Appearance’, springs immediately to mind). There is some tape wear evident in a handful of episodes, but on the whole the image is detailed and consistent throughout all thirteen episodes.

The original break bumpers are intact, and the episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3.

Audio

Audio is presented via a serviceable two-channel mono track. This is entirely functional and clear throughout. There are no subtitles.

Extras

Sadly, there is no contextual series.

Overall

A remarkable series that may nevertheless be too ‘talky’ for some viewers, The Guardians demonstrates engagement with a number of major issues of the 1970s, and in fact the series contains many striking parallels with debates in today’s society: Peter Wright (2005) asserts that The Guardians is ‘discomforting in its engagement with contemporary politics’ (296). The series is sharply-written and well-observed; it is also very thoughtful. The first few episodes could be said to ‘tread water’, circumventing a number of issues – hinting at conflicts and situations but not engaging with them fully. These episodes arguably spend a little too much time trying to set the scene for the drama that follows in the latter half of the series. However, the series picks up momentum in its fourth and fifth episodes, with the resurfacing of Tom Weston and the introduction of some fascinating moral dilemmas. (The episode ‘Appearance’, dealing with Weston’s experience in the rehabilitation centre, is arguably the best of the bunch.) It is a series that, as Peter Wright declares, is ‘[i]n hindsight […] remarkably prophetic, anticipating the economic and social upheavals under Jim Callahan’s Labour government and the early Thatcher administration’ (ibid.). The series was prescient in the 1970s, due to the high profile of radical political groups such as the Red Factions, domestic unrest (especially in Northern Ireland) and the problems with unemployment, inflation and industrial action that took place throughout that decade. The series also has striking parallels with today’s society and the fallout from the ‘War on Terror’, including the debates that surround some of the claims that measures have been taken to curb individual freedom (in the name of national security) and the ways in which these have been achieved via the manufacturing of consent. However, the series also seems to look backwards for its inspiration towards the Nazi occupation of France and the rich vein of literature, theatre, cinema and television that has focused on that period of history. With this in mind, The Guardians is a thought-provoking and rewarding series that benefits from repeat viewings. In its dystopic vision of a society dominated by unchallenged authority, The Guardians makes an interesting companion piece with the BBC’s series 1990 (1977-8), which with any luck will find a home video release someday in the future. References Tannenbaum, Percy H., 1980: The Entertainment Functions of Television. London: Routledge Wright, Peter, 2005: ‘British Television Science Fiction’. In: Seed, David (ed), 2005: A Companion to Science Fiction. London: Wiley-Blackwell: 289-305 Wright, Peter, 2009: ‘Film and Television, 1960-1980’. In: Bould, Mark et al (eds), 2009: The Routledge Companion to Science Fiction. London: Routledge: 90-101 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|