|

|

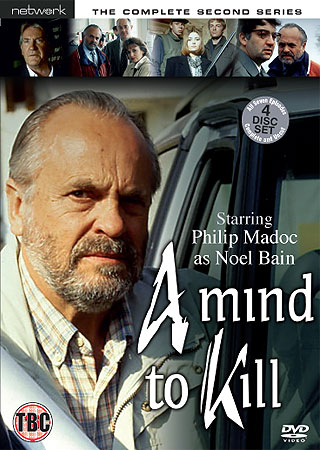

Mind to Kill (A): Series Two (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (23rd March 2010). |

|

The Show

Produced by Lluniau Lliw for broadcast on the Welsh television channel HTV (and, later, S4C), A Mind to Kill (1994-2002) was originally broadcast in England by Sky One and, in 1997, by the then-new terrestrial channel Channel 5. Growing out of a 1991 television film (of the same title), A Mind to Kill featured Philip Madoc as Detective Chief Inspector Noel Bain. Bain is a widower whose wife was killed by a drunk driver, and who has a sometimes rocky relationship with his adolescent daughter Hannah (Ffion Wilkins). The series was known in Wales as (Noson) yr Heliwr (which translates roughly as ‘Evening/Night of the Hunter/Huntsman’), and the majority of the episodes were filmed simultaneously in Welsh and English-language versions: the series was shown in Wales in a Welsh-language version, and the English-language versions were broadcast throughout the rest of the UK (see Price, 2002: en). This second series of A Mind to Kill was produced between 1995 and 1996; a third series was not produced until 2002, although a standalone episode, ‘Shadow Falls’, was made in 1998. ‘Shadow Falls’ was the first episode not to be filmed in a Welsh-language version (see the entry in the BFI’s Film and TV Database). However, ‘Shadow Falls’ was an anomaly: like the episodes from the first and second series, series three (broadcast in 2001/2) was apparently once again filmed back-to-back in both Welsh-language and English-language versions (see MGN, 2002: en). Throughout the 1990s, regional crime dramas became increasingly dominant on British television, largely springing from the popularity of Inspector Morse (Central, 1987-2000), which made prominent use of its Oxford setting. From Wycliffe (HTV, 1994-8), with its Cornish locations, to the Yorkshire-based A Touch of Frost (YTV, 1992- ) and Dalziel and Pascoe (BBC, 1996-2007), these regional crime dramas tended to have a clearly-defined formula, frequently foregrounding the relationship between an older detective with a younger colleague and placing an emphasis on the scenic qualities of the locations in which they are set (see Priestman, 2003: 241). As noted in Anthony Aldgate and Jeffrey Richards’ Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to the Present (1999), the regional crime dramas featured ‘more traditional, civilized, intuitive and reflective senior officers […] all of them provincial rather than metropolitan’ (145). Aldgate and Richards place the regional crime dramas in contrast with ‘social realist police dramas’ such as Cracker (Granada, 1993-2006) and Prime Suspect (Granada, 1991-2006). These social realist police dramas tended to foreground specific social issues and present their narratives with little of the ‘gloss’ associated with the regional crime dramas.

A Mind to Kill arguably straddles these two brands of television crime drama. The series has a strong sense of place, foregrounding its Welsh setting, and is mostly ‘provincial rather than metropolitan’, with most of the crimes taking place in rural settings. However, A Mind to Kill represents Wales as a hotbed of unrest and repressed violence, in contrast with many of the other regional crime dramas – which often go to great lengths to depict the crimes at the centre of their narratives as atypical of the region. Where many of these regional crime dramas feature small communities that are shocked by the crimes investigated by the detectives, in A Mind to Kill the crimes Bain investigates are frequently nothing more than the tip of the proverbial iceberg; as in Cracker, the crimes reveal to Bain the rifts within society. Rather than being a rural idyll, the Wales in A Mind to Kill is a place of casual violence, unemployment and petty crime. In the second episode of this series, ‘Death Watch’ (‘Pengwern’ in Welsh), Bain is forced to investigate the vigilante killing of a man. Bain’s investigation takes him onto a rural estate that is divided by crime and class differences. Timothy Wren (Gareth Lewis), one of the locals apparently associated with a vigilante group working within the area, tells Bain, ‘See that estate up there? Bandit country, that. They’d rob themselves if there wasn’t anybody else to rob, those bastards would’. A local woman tells Bain that the vigilantes ‘deserve a medal’, commenting on the inhabitants of the estate that ‘They’d piss in their own kitchen, some people’. The locals have little faith in the police; Wren tells Bain that ‘you lot couldn’t find Mel Gibson in a bag of chips’. Later, one of Bain’s officers tells Bain that ‘You’re not going to get anything out of them [the people on the estate]: there’s no community here. If I had my way, I’d build a wall around the place and chuck raw meat in every now and then’.

Some of the local youths from the estate attack the shop of Spencer Jones (Wynford Ennis Owen) due to Jones’ association with the vigilantes, after it is discovered that the dead man is a local petty criminal named Wayne Evans (Mark Cass). A small riot takes place outside the shop, and the youths plot to burn Jones’ shop down. When Bain tries to stop them, the youths show no respect for the law. The series offers a snapshot of rural Wales at the ‘fag end’ of the 1980s: the area is shown as ridden with strife, troubled youth and unemployment; the local estate is populated by an underclass with little concern other than for themselves. The subsequent episode, ‘Game Plan’ (‘Peirriant Lladd’) sees Bain sent undercover as a tourist to one of Wales’ seaside resorts, where Bain is ordered to investigate the murder of a young woman. The episode offers a naturalistic, grubby representation of Britain’s declining coastal resorts. In his investigation, Bain uncovers a local pornography racket, with the town’s costumier (Huw Tudor) filming some of the local girls and selling the tapes to tourists and locals. Bain also discovers that the locals have nothing but contempt for the visitors to the town: one of the locals confesses that ‘I shouldn’t speak ill of the dead, but I’m glad to see the back of them’; he claims that the ‘seasonal crowd’ are ‘a bunch of headbangers’, stating that ‘It’s alright for them, but some of us have to live here’. Bain himself provides a contrast to the detectives found in the regional crime dramas popular during the 1990s. Where regional crime dramas such as Wycliffe and Dalziel and Pascoe tended to place the methods of their ‘traditional, civilized, intuitive and reflective senior officers’ in juxtaposition with those of their younger colleagues, in A Mind to Kill Bain mostly works alone, although in many of the episodes he is intermittently shadowed by Detective Sergeants Alison Griffiths (Gillian Elsa) and Carwyn Philips (Geraint Lewis). Bain is also a more morally complex protagonist than Wycliffe, et al. Played with gravitas by the great Philip Madoc, throughout the series Bain struggles to come to terms with the death of his wife at the hands of a drunk driver. In marked contrast with the English regional procedural dramas’ generally more conservative protagonists, Bain also firmly believes in retaliatory violence: in the penultimate episode of this second series, ‘Strange Territory’ (‘Bro Dirgelion’), Bain reflects on the Webb family’s beating of the man (Karl Stranger, played by Ioan Gruffud) suspected of the murder of their daughter. Bain tells a colleague that ‘If someone touched Hannah, I’d do exactly the same. Sometimes putting them in prison just isn’t enough’. Later, discussing the issues of revenge with his daughter Hannah, Bain comments, ‘Revenge. It’s a natural impetus [….] It makes people feel better, and that gives popular support to the rule of law. Retribution; people feel that justice has been done [….] The system of justice. What we have now, nobody feels satisfied. The criminal perhaps; certainly not the victim. And that’s why we have no popular support for the rule of law [….] It [revenge] calms, it purges [….] I would like the man who killed your mother to suffer. Time hasn’t changed that’. The climactic episode of this second series, ‘Green Wounds’ (‘Y Graith’), brings together these two aspects of Bain’s character. In this episode, Bain is forced by Superintendent Bevan (Meic Pover, who also wrote this series’ episode ‘Inheritance’) to undertake counseling. Bevan believes that Bain, who has been suffering flashbacks to the death of his wife, is likely to suffer a breakdown. The doctor who questions Bain advises Bevan that Bain should ‘take a break, a long one’, but Bain protests that ‘Giving me time to dwell on things isn’t going to help. I need to work [….] I’ll get through it’. Bain then goes on to dismiss the therapist’s findings as ‘Psychobabble [….] Bollocks’. After telling Alison that ‘personal vengeance may be all that’s left’, he reminds her that ‘The vandals are at the gates of Rome, Alison, and there’s only us between them and anarchy’.

Making use of his time off work, Bain sets out for revenge against the man who he believe killed his wife, David Caulfield (David Warner). Using an assumed identity, Bain inveigles himself into Caulfield’s life. In a plot that draws parallels to Patricia Highsmith’s 1950 novel Strangers on a Train (and Hitchcock’s 1951 film adaptation, which in a postmodern way is directly referenced in this episode), Bain attempts to set a trap for Caulfield, drugging him and persuading him that Caulfield commissioned Noel to kill Caulfield’s estranged wife Melanie (Carol Drinkwater). However, a parallel narrative is developed, in which Paul Tam (Richard Harrington), who blames the death of his criminal brother Matthew (Dorien Thomas) on Noel, seeks revenge against Bain by targeting Hannah. The result is a powerful episode that explores issues of regret and revenge, with Tam‘s desire for revenge against Bain placed in juxtaposition with Bain‘s need to avenge his wife’s senseless death. However, despite the series’ differences from the conservative regional crime dramas that populated British television throughout the 1990s and 2000s, some of the episodes of A Mind to Kill are fairly reactionary. The aforementioned ‘Game Plan’ features a killer whose murders are triggered by video games and pinball machines, with each of the murders being intercut with close-up shots of a pinball machine and an ominous mechanical voice laughing deeply before declaring ‘Off with their heads’. The episode’s original broadcast took place at a time, in the mid-1990s, of a series of high-profile moral panics about violence in films and video games, and the episode takes a fairly technophobic stance towards the issue, playing into mid-1990s paranoia about video games and pornography triggering violent behaviour (see Clarke, 2003: 132). The killer is an otherwise meek man who is addicted to both the costumier’s homegrown pornography and the video games in the local arcade. In a roundabout way, the episode suggests a relationship between pornography, the video games and the murders (Bain is told that ‘there was a link between those [pinball] machines and the murder of those two girls’) but never goes so far to state what exactly this relationship is; the killer’s rambling statement at the end of the film fails to clarify matters (‘Stopped going in the bedroom, stayed downstairs, watched my videos. Friends they are, like the pinball machines, except they let you down, leave you. Whores they are, makes you a bit angry. I expect you want to know about the girls. Dirty, dirty, dirty, dirty’).

The episode ends with Bain visiting the killer’s wife and infant son, who are as obsessed with and hypnotised by video games as the killer was. ‘Do you mind if I switch this off?’, Bain asks the killer’s wife, a look of concern playing across his face as the images from a video game being played by the young boy flicker across the woman’s face. The scene is shot from the point-of-view of the television set in the corner of the room; the woman’s face is passive, and she is transfixed by the screen and the lights and sounds emanating from it. As the screen fades to black, the child can be heard giggling; in the context of the episode, the child’s laughter at the video game is chilling. The implication is clear: the games, which the episode posits can trigger latent psychosis and violence, are seductive and their unquestioning infiltration into everyday life should be questioned. However, coming from a series whose focus is death and murder, the message is more than a little mealy-mouthed. Filled with Celtic angst, A Mind to Kill also has moments of genuine horror, frequently using a Freudian ’primal scene’ as a pivotal narrative device. For Freud, the primal scene took place when the child observed her/his parents involved in the sex act, which the child interprets as an attack by the father on the mother. Memories of this traumatic primal scene cause anxiety in the child (see Freud, 2003: 227-43). The concept of the primal scene has been widely applied to horror films, films noirs and baroque European thrillers, especially in sequences in which the protagonists are haunted by a traumatic half-remembered memory, or in which they are positioned as ‘anonymous spectators’ to something beyond their comprehension. In The Monstrous Feminine, (1993) Barbara Creed suggests that the ‘birthing’ scene in Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) is a classic example of the primal scene: when the crew members watch helplessly as the alien bursts out of Kane’s (John Hurt) chest, they are traumatised and, like the child in Freud’s primal scene, unable to explain or understand what they are witnessing (17-9).

With its protagonists who are frequently haunted by a past trauma, films noirs contain many examples of the primal scene. One of the most overt examples is Ted Tetzlaff’s 1949 film The Window, in which young Tommy Woodry (Bobby Driscoll), whilst sleeping on the fire escape of his apartment building, glimpses his neighbours attacking and killing an unknown man. Other examples of the primal scene in films noirs can be found in The Locket (John Brahm, 1946), Burt Kennedy’s 1976 adaptation of Jim Thompson’s novel The Killer Inside Me, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers (Lewis Milestone, 1946) and postmodern films noirs such as Blue Velvet (David Lynch, 1985) (see Spicer, 2002: 79, 145; Krutnik, 2007: 9; Creed, 1988: np). The primal scene is also integral to the baroque European thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s (and, in particular, the Italian thrilling all’Italiana, more popularly known by English-speaking fans as gialli). In Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) is an unwitting witness to a murder in which it is unclear who is the aggressor and who is the victim; Argento’s Deep Red (1975) opens with a primal scene in which a child is witness to an act of violence; the narrative of Tenebrae (1982) hinges on the protagonist’s (Anthony Franciosa) half-formed memories of a primal scene of sexual humiliation (see Hunt, 1992: 329; Mullen & O’Beirne, 2000: 30-3). The narratives of these films often hinge on the re-enactment of a specific primal scene (often via on-screen analepses): citing Slavoj Zizek, Xavier Mendik asserts, ‘Following Lacan’s celebrated reading of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Purloined Letter,” the narratives of detective and analyst confirm these clues [the fragments of events that must be pieced together] as pointing to the revisions or repetitions of real or imagined primal trauma’ (2002: np). Modern forensic science-themed television shows such as CSI (CBS, 2000- ) arguably consolidate this tradition of crime cinema’s interest in the primal scene, with their constant re-enactment and fetishisation (in CSI’s case, via computer-generated extreme close-ups) of the crime that the detectives are investigating. As in films noirs and European thrillers, in A Mind to Kill many of the killers are haunted by memories of a ’primal scene’. In ‘Inheritance’ (‘Trefradaeth’), the strange young man Garmon Pritchard (Jeremi Cockram) is haunted by memories of a half-remembered incident from his past. He begins a sexual relationship with an older woman, Ruth Barra (Melanie Walters). Barra is distrusted by the locals because she is an ‘outsider’, an apparently independent, sexually-liberated ‘new’ woman who has moved to the area from England; however, her neighbours go to great lengths to assert that she has ‘learnt Welsh’ and therefore attempted to inveigle herself into their community. Pritchard is seduced by Barra and, in a moment of dissociation, sees himself watching the scene as a third party; the scene is an odd moment that is more than a little suggestive of Freud’s ‘primal scene’. The Freudian overtones of the scene are compounded when, in the morning, Pritchard refers to Barra as ‘Mammy’. In ‘Strange Territory’, Bain is confronted with a school librarian, Myrrdin Greene (Mel Jones), who claims to be psychic. The apparently simple-minded Jones has been experiencing visions since he was four years old. When a young girl is abandoned by her boyfriend near a Welsh castle, she is seen by Jones. He suffers nosebleeds and blacks out, experiencing nightmarish hallucinations of the girl’s murder. The half-repressed memory of the attack on the girl once again calls to mind Freud’s ‘primal scene’. Bain struggles with the case, believing that Jones’ visions are nothing more than ‘mystical nonsense’: as Jones cannot account for his whereabouts during the murder, he becomes a suspect in the case. Some of the episodes have more direct intimations of Freudian themes of incest, in particular Jung’s notion of the Electra complex. In ’Bloodline’ (‘Grym Gwaed’), the elderly Sir Isaac Gwillyn (David Lyn) carries out a sexual relationship with his stepdaughter Catrin (Noni Lewis): ’It’s not much to pay’, she tells him after demanding five hundred pounds; ’Do you want me to call you “daddy”, like I used to?’ The episode juxtaposes Sir Isaac’s relationship with Catrin, with its suggestions of sexual deviance, with Bain’s thorny relationship with Hannah, who during the course of the episode discovers she is pregnant. Meanwhile, in a scene that in the context of any other crime drama would seem fairly incongruous but in the Freudian nightmare presented by A Mind to Kill seems loaded with meaning, in ‘Strange Territory’ Hannah begins a relationship with a sleazy university lecturer, Laurie Bowen (Jeff Thomas) and, during one scene, directly compares Bowen to her father. In its intermittent overtly Freudian content and its concern with the relationships between issues of sexual deviance and murder (frequently tied to ‘primal scenes‘ that are obsessively replayed throughout the narrative), A Mind to Kill shares some of the traits of classic films noirs and European thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s. In discussing Cracker in their book Reading Between Designs (2003), Britton and Barker claim that the series alludes strongly to the conventions of films noirs through its depiction of ‘horrifically violent, often sexually charged cases’ (201); the same is true of A Mind to Kill. Like Fitz (Robbie Coltrane) in Cracker, Bain is depicted as—like the traditional protagonist of film noir, epitomised in the roles associated with actors like Dana Andrews (Where the Sidewalk Ends, Otto Preminger, 1950), Glenn Ford (The Big Heat, Fritz Lang, 1953) or Robert Ryan (On Dangerous Ground, Nicholas Ray, 1952)—walking a fine line between socially-acceptable behaviour and deviance. Like films noirs, the episodes of A Mind to Kill feature characters who are haunted by their pasts - not least of which Bain himself, who is tormented by his wife’s death. Always siding with the underdog, Bain has a thorny relationship with the powerful. He displays thinly-veiled contempt for Superintendent Bevan, his deskbound superior officer who, in ’Game Plan’, continually demonstrates poor judgement. In ‘Bloodline‘, Bevan suggests that Bain should not try to investigate Sir Isaac; Bain replies, matter-of-factly, by telling Bevan that ‘I know he‘s rich and powerful and he‘s got friends in high places, but he‘s not above the law‘.

‘Head of the Valley’ (‘Y Pris’) focuses in detail on Bains attitudes towards wealth and power. In the episode, Bain investigates the five year old murder of Philip Evan. The wealthy Williams family, consisting of mother Ellen (Margaret John) and her two sons George (Dafydd Hywel) and Ian (Jon Tregenna), commissioned a veteran of the Falklands conflict, Keith Southey (Simon Fisher), to kill Evan. Bain once did a favour for Edward Williams, Ellen’s late husband, letting him off with a caution when Bain was a lowly police sergeant. In Ellen’s words, Bain caught Edward ’with a slut. If it had gone to court, he would have been ruined’. However, Bain goes to great lengths to point out that his reasons for giving Edward a ’pass’ had little to do with Edward’s status: Bain tells Ellen that ’A lot of men would have lost their jobs, Mrs Williams [….] Your husband was a very powerful man; I was a newly-promoted sergeant, keen on natural justice’. As the plot unravels itself, Bain clearly regrets giving Edward a ’pass’ but feels righteous in the knowledge that he did it for the benefit of Edward’s employees. At the end of the episode, Bain angrily tells Ellen, ’Don’t play the wounded innocent with me, for God’s sake. This family has had its grubby little fingers in every profitable pie in South Wales for the last thirty years, from local government fiddles to fly dumping sites. If there was money there, your clan was in there, making sure it got it; and it didn’t care how it did it’. This second series features a couple of ongoing narratives, including Bain’s burgeoning relationship with pathologist Margaret Edwards (Sharon Morgan) and his decision to sell the family’s house, against the wishes of Hannah, and move into a lonely flat. The latter ongoing narrative strand recalls the contemporaneous American television series Millennium (Fox, 1996-9), in which FBI profiler Frank Black’s (Lance Henriksen) house was initially used as a defence from the horrors of his work but gradually came under siege by the dark nature of Frank’s work. Although probably not a big hit with the Welsh tourist board, A Mind to Kill is a fantastically dark television drama, filled with Celtic angst and ritual; although some of the episodes could benefit from some editing and tightening, on the whole the series is densely-plotted, moody and satisfying. Anchored by a consistently strong performance from Philip Madoc, A Mind to Kill is frequently dark and sometimes outright nightmarish. The episodes also eschew the structural conventions of many television crime dramas: for example, ‘Bloodline’ presents its narrative in a largely non-linear manner. Leaving aside Cracker, which rapidly acquired classic status, A Mind to Kill is arguably the best, and most thought-provoking, of the 1990s regional crime dramas. Each episode is a little over ninety minutes long, produced for broadcast in a two hour slot on commercial television. There do not appear to be any edits in the episodes presented here.

Disc One: 'Bloodline' (96:31) 'Death Watch' (96:06) Disc Two: 'Game Plan' (95:03) 'Inheritance' (94:03) Disc Three: 'Head of the Valleys' (93:34) 'Strange Territory' (94:11) Disc Four: ‘Green Wounds’ (94:17)

Video

In our review for Network’s release of the first series, I noted that some of the episodes demonstrated evidence of tight framing, and the first episode in the set (‘White Rocks’) presented its opening and closing credits in a widescreen ratio of around 1.66:1. Other contemporaneous dramas, such as Cracker, were being shot in 1.66:1, and I seem to recall that Channel 5 screened episodes of A Mind to Kill in that ratio too. (Early episodes of Cracker have been released to DVD in non-anamorphic 1.66:1.) The episodes in the second series are presented in 4:3, but once again there is some tight, off-centre framing that might suggest the episodes have been slightly cropped. However, without access to recordings of the original broadcast versions of the episodes it is impossible to assert with any authority whether this is the screen ratio of the original broadcast versions of the series. If there is any cropping, it is only minor and does not impact on the quality of the series.

A Mind to Kill is a visually interesting series, making moody use of its Welsh locations. These DVDs contain an excellent presentation of the series, retaining the show’s gritty (and occasionally grainy) aesthetic. The fact that the episodes are shot on film adds greatly to their noir-ish design.

Audio

The series is presented with a two-channel stereo track, which is well-balanced and clear. The series makes subtle and effective use of atmospheric music, including its main theme - a haunting arrangement that features prominent use of pan pipes. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

There are no extra features. Considering the series was shot simultaneously in Welsh and English, it is a shame that the Welsh-language versions of the episodes (or at least some clips of them) are not contained on this DVD release. Some form of contextualisation would have been enormously helpful too, as very little seems to have been published about the series.

Overall

An excellent series, A Mind to Kill is in marked contrast with many of the ‘cosy’ regional crime dramas of the 1990s. The series is more closely aligned with Cracker, although it is often a little more reactionary than that great series. Madoc delivers a consistently excellent performance as Bain; the series’ treatment of the crimes around which the narratives revolve are frequently nightmarish and highlight relevant social issues - much like Cracker. Again, as like Cracker, A Mind to Kill calls to mind classic films noirs and European thrillers, in its focus on crimes of obsession and its solitary hero. Fans of these dark genres of crime cinema should find much to enjoy here. References: BFI Film and TV Database entry for ‘Shadow Falls’: http://ftvdb.bfi.org.uk/sift/title/611016 Aldgate, Anthony & Richards, Jeffrey, 1999: Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to the Present. London: I. B. Tauris Clarke, David, 2003: Pro-Social and Anti-Social Behaviour. London: Routledge Creed, Barbara, 1988: ‘A Journey Through Blue Velvet’. New Formations (Winter 1988) [Online.] http://www.amielandmelburn.org.uk/collections/newformations/06_97.pdf Creed, Barbara, 1993: The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. London: Routledge Freud, Sigmund, 2003: The ‘Wolfman’ and Other Cases. London: Penguin Hunt, Leon, 1992: ‘A (Sadistic) Night at the Opera: Notes on the Italian Horror Film’. In: Gelder, Ken (ed), 2000: The Horror Reader. London: Routledge: 324-35 Krutnik, Frank, 2007: ‘Un-American’ Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era. Rutgers University Press Mendik, Xavier, 2002: ‘Transgressive drives and traumatic flashbacks’. KinoEye (2:12) [Online] http://www.kinoeye.org/02/12/mendik12.php MGN, 2002: ‘Phil’s the Bain of the murderer’s life’. Wales on Sunday (7 July, 2002): en Mullen, Karen & O’Beirne, Erner, 2000: Crime Scenes: Detective Narratives in European Culture Since 1945. Amsterdam: Nodopi Price, Karen, 2002: ‘Inside the mind of a killer’. Western Mail (13 July, 2002): en Priestman, Martin, 2003: The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction. Cambridge University Press Spicer, Andrew, 2002: Inside Film: Film Noir. London: Pearson Education For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|