|

|

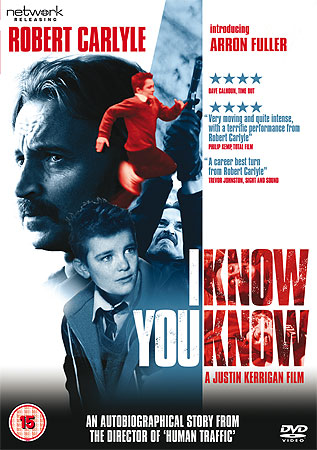

I Know You Know

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th June 2010). |

|

The Film

I Know You Know (Justin Kerrigan, 2008) Directed by Welsh filmmaker Justin Kerrigan, I Know You Know is arguably as radically different from Kerrigan’s debut feature, Human Traffic (1999), as possible. Where Human Traffic offered a fast-paced, bold and brash look at youth culture in the late 1990s, I Know You Know delivers an intimate examination of the relationship between a father and his son, and a sideways glance at the social and economic decline of South Wales in the 1980s.   I Know You Know takes place in South Wales in 1988, and begins with Charlie Callahan (Robert Carlyle) preening in a mirror, the camera positioned where the mirror should be, and addressing the audience directly, his words providing an interior monologue: ‘Everything’s under control’, he says: ‘Just tell me what I need to do to get out of here, and it’s done. Just give me the nod’. The film then offers an extended analepsis that begins with Charlie and his son Jamie (Arron Fuller) returning to Wales by aeroplane, after a trip to Amsterdam. Charlie is met by a man named Fisher (David Bradley), who Charlie states works for ‘the agency’. Soon, Charlie is enlisted by Fisher into committing an act of espionage against Astrosat, a satellite broadcasting company. For this, Charlie tells Jamie, Charlie will be paid ‘two million quid’, allowing Charlie and Jamie to run away to America. Meanwhile, Charlie struggles to fit in at school, finding himself the target of a group of obnoxious bullies. He also comes into conflict with Charlie’s uncle Ernie (Karl Johnson) and aunt Lilly (Valerie Lilley), into whose care Charlie has placed him, finding his father’s life as an undercover operative more exciting. However, after running away from his aunt and uncle’s house and rejoining his father, Jamie begins to see a darker side to his father, and he is eventually forced into the realisation that his father’s work as a secret agent may be nothing more than a complex fantasy.  The revelation that Charlie’s status as a ‘secret agent’ is a fiction created by Charlie himself, comes as no surprise due to Charlie’s reliance on the clichés of the espionage genre: Charlie’s cliché-driven claims about his work (for example, his early assertion that Fisher represents an unnamed organisation known as ‘the agency’) signpost the fact that he is living a life of fantasy. Kerrigan’s coup comes in representing Charlie’s interior narrative, revolving around Astrosat, as frighteningly real: in the film’s early sequences, television adverts for Astrosat are interspersed throughout the narrative (like the propagandistic ‘media breaks’ in Paul Verheoeven’s RoboCop, 1987) and billboard advertisements for the company seem omnipresent; the preponderance of advertising for Astrosat makes the company (and its logo) seem threatening, giving credence to Charlie’s paranoia. When Charlie apparently tells Fisher over the telephone that 'They're everywhere, Mr Fisher. All roads lead to Astrosat', the film has provided us with visual evidence that Astrosat is indeed ‘everywhere’.    Later, as the nature of Charlie’s delusions become apparent to both Jamie and the audience, Charlie tells his son that 'They're [Astrosat] the enemy, Jamie [….] They've got the ultimate weapon now, mind control. They're going to put up satellite dishes in every house in the country. They're going to tell people what to think, what to buy, who to vote for, till they're brainwashed, still thinking that they're free. We've got to stop the signal. Try to explain this to anyone, they'd think you were crazy'. However, there is an element of truth to Charlie’s paranoid ramblings, reflecting concerns during the 1980s about the growth of corporate media (via satellite broadcasting) and, more pertinently, the social and economic power of certain large media corporations. Perhaps not incidentally, the year in which the film is set (1988) was also the year in which Rupert Murdoch declared that Sky Television would begin broadcasting in the UK, further consolidating Murdoch’s hegemonic dominance of the media landscape within the UK (which, when Sky Television began broadcasting in 1989, resulted in the Labour Party calling for a Monopolies and Mergers Commission inquiry into Murdoch’s company’s cross-media interests). Charlie’s grand claims are set against the declining urban landscape of Wales in the 1980s, an environment of pebbledashed terraced houses and run-down comprehensive schools; in the closing sequences, it is revealed that Charlie’s delusions of grandeur, his construction of a secret life in which he is a potent secret operative, are a direct outcome of the socio-economic state of South Wales at the end of the 1980s. His retreat into a fabricated scenario, and his fantasies of empowerment, are revealed to be the outcome of the collapse of Charlie’s business as an independent travel agent when the council kicked Charlie out of his premises in favour of Astrosat, destroying Charlie’s business and leaving Charlie in debt to the council. The film thus pits the individual against the corporate hegemony, offering a representation of the human victims of the increasing power of the corporate worldview during the 1980s: aside from Charlie’s financial decline, the film juxtaposes the social and economic poverty of South Wales during this era with the increasing power of corporate entities such as Astrosat. As Charlie bitterly notes towards the end of the film, 'Worked so hard, so many years. Still got nothing. Stuck in this poxy fucking flat'.  The film is at times frightening, especially when the full extent of Charlie's delusions begin to make themselves clear, and Charlie attempts to persuade Jamie to use a domestic kettle as a means of communicating with 'HQ'. However, it is also very touching, most notably in the final sequence. Both Robert Carlyle and Arron Fuller give excellent performances as Charlie and Jamie. Their relationship, in which Jamie is allowed to address his father by his first name, rings true; although the whereabouts of Jamie’s mother is never mentioned directly, we are led to presume that she has passed away (‘I can’t remember what my mum looks like’, Jamie tells one of the boys at school). The film has a strong sense of place, both in terms of geography and time: the attention to period detail, evidenced in the décor, cars and costumes, is evocative of the era, despite some curious, and forgivable, anachronisms in the film’s representation of youth culture – Jamie’s costume sometimes seems more representative of modern youth culture, and when Jamie is knocked to the floor by the school bully one of the bully’s companions makes a noticeable use of modern slang when he declares ‘Bring the noise. Come on, knock him out, Dean. That was sick’. The film runs for 78:47 mins (PAL) and is uncut.

Video

The film is presented in its original theatrical aspect ratio of 1.85:1, with anamorphic enhancement. The film begins with a vivid colour palette, dominated by lots of golden oranges and yellows, as if tinted by nostalgia and Charlie’s romanticised version of his life; but as the film progresses and the nature of Charlie’s delusions becomes apparent to both Jamie and the audience the film’s aesthetic becomes more drab and dominated by browns and greens. The transfer handles this transition well, and makes effective use of rich, deep blacks in the interior scenes set in Charlie’s flat.

Audio

The DVD contains a two-channel audio track, which includes some surround encoding. There is nothing too ‘showy’ here, though: the sound is crisp and clear, mostly positioned at the front of the soundscape. The score encompasses a subtle pastiche of some recognisable tunes (such as The Shadows’ ‘Apache’). There are no subtitles.

Extras

The DVD contains two features: a trailer (1:22), which places emphasis on the early portion of the film and arguably misrepresents the picture as a movie about a secret agent; and Director's Video Diaries (7:50), in which Kerrigan explores the autobiographical elements of the plot (and its roots in his own relationship with his father) and the reasons why it took him over eight years to make another film after his debut, Human Traffic. There are also a range of bonus trailers, which play on disc start-up and are skippable.

Overall

I Know You Know is in many ways an excellent film, offering a very touching subject in the relationship between Charlie and Jamie, and containing a detailed, human representation of the social landscape of South Wales in the late 1980s. The film offers a subtle challenge to the hyperbole of Hollywood-style espionage blockbusters, exploring the role that these fictions play for men such as Charlie, who has been disenfranchised by the growth of the corporate sensibility during the 1980s. As noted above, Charlie’s paranoid fantasy has an element of truth to it, and is very much rooted in the cultural landscape of the late 1980s; aside from a few minor anachronisms, the film has a very strong sense of time and place. Fans of Kerrigan’s Human Traffic who expect more of the same, may find I Know You Know frustrating due to its more low-key approach to its subject matter. However, I Know You Know is a compelling drama with both a human face and social conscience, and it deserves to be widely-seen. For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|