|

|

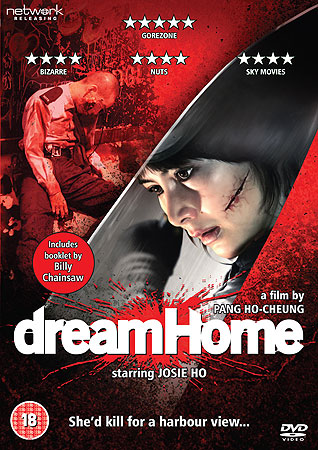

Dream Home AKA Wai dor lei ah yut ho

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (26th March 2011). |

|

The Film

Dream Home (Ho-Cheung Pang, 2010)

Hong Kong cinema attracted much international critical attention in the 1980s, following the success of John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986): as Karen Fang (2004) notes, ‘in the mid-1980s Hong Kong film, despite its innovation and local popularity, still remained largely below the global radar, visible overseas only in Chinatown theatres, occasional cult festivals, and the videocassettes that fans – mostly Asian immigrant viewers – circulated among themselves’ (65). Woo’s film managed a ‘breakout’ success ‘by attracting a flurry of critical and commercial attention on the festival circuit’ (ibid.). Much of this attention was directed towards the action films that Hong Kong was producing (known locally as yingxiong pian/‘hero’ films), such as the pictures of Wong Jing (God of Gamblers, 1989), Johnnie To (The Big Heat, 1988) and Ringo Lam (Full Contact, 1992; City on Fire, 1987); amongst English-speaking fans, this unique genre attracted the label ‘heroic bloodshed’, a phrase coined by Rick Baker in the pages of the magazine Eastern Heroes (ibid.: 62; Logan, 1996: 126). However, at the same time, Hong Kong cinema was also producing a cycle of horror films that found favour with English-speaking fans whose interest in Hong Kong cinema had been piqued by the breakout success of A Better Tomorrow (Gelder, 2000: 365). These films included a range of ‘hopping vampire’ films (Mr Vampire: Ricky Lau, 1985), more traditional ghost stories (Chinese Ghost Story: Siu-Tung Ching, 1987) and more explicit ‘Category III’ horror films such as Dr Lamb (Danny Lee, 1992) and The Untold Story (Herman Yau, 1993). It has been suggested that the ‘Category III’ horror films – which acquired their name due to the adults-only ‘Category III’ classification, created in 1988 and an index of the films’ strong violent and/or sexual content – offered a subversive critique of Hong Kong society: in the words of Tony Williams (2005), films such as Dr Lamb, The Untold Story and The Underground Banker (Bosco Lam, 1994) ‘are all set in a lower-depths environment representing the dark side of the Hong Kong economic miracle’ (205). The majority of these films take place in ‘subsidized housing, much of it in dense, high-rise dwellings that sit alongside production sites and commercial facilities in the New Territories’ where the majority of Hong Kong’s non-affluent population lived ‘in extremely cramped living conditions’ (Stokes & Hoover, quoted in ibid.). The group of Category III films cited above ‘often represents an irrational bloodthirsty revenge by a low-income proletariat against forces they perceive as oppressive. It is unorganized, random, and chaotic, highly-characteristic of a society well known for its political apathy’ (ibid.: 206). The films, many of which foreground the theme of social exclusion, were made for a largely working-class audience ‘who cannot easily afford entry to the latest Hollywood blockbusters’ and ‘appeal to audiences who will never fully achieve the financial rewards of the Hong Kong society by depicting the stressful nature of surviving at the lower depths’ (Stringer, quoted in ibid.). Although made twenty years after the boom of Category III horror films, Dream Home – which has also acquired a Category III classification (in a cut form) in Hong Kong – reflects on the 1980s, the era in which the original Category III films were produced, whilst also offering a view of contemporary Hong Kong society from the perspective of the ‘lower-depths’. Told in a non-linear style from the perspective of its protagonist, Cheng Lai Sheung (Josie Ho), Dream Home opens with a declaration that ‘A 2007 survey listed the average monthly income in Hong Kong as HK$10,100. But 24% of people are below the average income. Since the handover, income in Hong Kong has increased by 1%. But in 2007 alone, house prices shot up by 15% [….] In a crazy city, if one is to survive, one has to be even crazier’.

Cheng lives a miserable life, working two soul-destroying jobs, taking care of her seriously ill father and conducting an unrewarding affair with a married man (Eason Chen). Through analepses, we are shown glimpses of Cheng’s childhood in one of the cramped high-rise buildings mentioned above, typical of the homes of the working-class citizens of Hong Kong. When Cheng’s father said that the family would move, Cheng prayed for a flat with a view of the sea. Meanwhile, landlords are seen throwing snakes into the flats of the high-rise block in which Cheng’s friend Jimmy lives, presumably to drive them out and make way for redevelopment: after we are shown a banner stating that ‘The government colludes with property tycoons to evict us. The government are a bunch of gangsters’, we see the high-rise flats being demolished.

In the present (identified by an onscreen title as 2007; in other words, pre-recession), Cheng works by day as a telemarketer for Jetway Bank and by night as a saleswoman in a shop; after the opening credits, we see her trying unsuccessfully to sell a new account to customers via telephone. Outside, on their cigarette break, Cheng and her colleagues discuss the loans they are made to sell to customers. One of Cheng’s colleagues declares, ‘If someone wants to borrow money, and someone wants to lend money, then nobody loses’. In response to this, Cheng asserts that ‘If someone can’t pass the TU credit report, it means they can’t pay off the debt. It’s almost like we’re driving people to a kind of hell’. When, in a later sequence, the same group of friends plan a holiday in Japan, telling Cheng that ‘We earn money to spend money’, Cheng asserts that if she went on holiday, ‘It’ll only take a few days to spend all my savings […] I want to save up and buy a flat’. The flat Cheng desires is ‘No 1, Victoria Bay’. Her friend responds, ‘Come on, that one is so far away and expensive, why?’, and another (male) friend asserts, ‘Life is too short. I don’t want to waste my life on a mortgage’. However, for Cheng the luxury flats in Victoria Bay, with their view of Victoria Harbour, represent the fulfilment of her childhood dream.

Cheng has a secret: by night, she stages a series of vicious murders in the Victoria Bay building, in an attempt to drive down the price of the flat that she wants to buy. Cheng is first introduced to us in the pre-credits sequence. The film opens with a series of shots meant to simulate the view from CCTV cameras in the Victoria Bay building; the empty corridors are devoid of human life, and the security guard who is supposed to be watching the monitors is asleep. Cheng enters, surprising the security guard and attacking him with a heavy hammer. She ties a plastic cable tie around his throat and, in desperation, he tries to cut the tie with a utility knife, the blade slicing into his own throat. This is the first of many excessively violent murders that, in their representation of murder-as-spectacle, recall the violent set-pieces associated with the thrilling all’italiana/gialli films of the 1960s and 1970s (for example, Mario Bava’s Sei donne per l’assassino/Blood and Black Lace, 1964; Dario Argento’s Profondo rosso/Deep Red, 1974). In its focus on a series of murders committed over a desirable property, Dream Home is most directly reminiscent of Mario Bava’s Reazione a catena/Bay of Blood (1971), in which a brutal series of murders takes place over a desirable area of land.

Some of the murders in Dream Home are disturbing (in one sequence, Cheng binds a pregnant woman and suffocates her with a vacuum bag) and others are blackly comic (in a later sequence, Cheng disembowels a stoner who then tries to smoke a joint whilst surrounded by his own viscera). They are all inventive and incredibly explicit – which may endear the film to some viewers and alienate others. However, what is arguably the most upsetting sequence is much more subtle: in a heartbreaking scene, Cheng sits on the end of her elderly father’s bed as, dying from asbestos poisoning, he reaches out for her but finds that his daughter simply moves out of his reach and lets him quietly slip away. Unusually told entirely from a female perspective, the film also contains a subtle critique of the chauvinistic culture of Hong Kong. Cheng is conducting a soulless affair with a married man, and she arranges to meet him in a seedy hotel. Arriving at the hotel before her lover, Cheng flicks through the channels on the television set in the hotel room and stumbles across some misogynistic pornography. The atmosphere of male exploitation is consolidated when Cheng’s drunken lover arrives and tells her a ‘joke’ about a Korean man whose girlfriend wanted to break up with him. ‘You know Korean men like to beat women’, he tells her. When the Korean man asks his girlfriend why she wants to break up, ‘She said, if you do care about me, then why don’t you beat me? You’ve never beaten me, not even once […] I’m always out late, but you never beat me’. When Cheng wakes up the next morning, she finds that her lover has gone and she is left to pay for the hotel room. This theme is revisited later when one of the Cheng’s victims is revealed to be a man who lives with two women. In another scene, Cheng’s relationship with her married lover verges on prostitution when, after performing oral sex on her boyfriend, she asks him to lend her some money for an operation that her father needs. Cheng’s lover asks her why she doesn’t use the money she’s saved for her flat, but Cheng responds by protesting that ‘the experts’ think that now is the best time to buy a property: she would rather put the money towards the flat she desires than spend it on the operation that her father needs.

The film contains equal amounts of gore and social commentary. There were reputedly disagreements between director Pang Ho-Cheung and star Josie Ho, who also produced the film. These disagreements revolved around the final cut of the film, although it has to be said that in the completed version the balance of social commentary and more traditional horror elements is pretty strong. Like the Category III films of the 1980s and 1990s, Dream Home offers a view of Hong Kong society from the bottom up, highlighting the ways in which the working-classes and the lower middle-classes are exploited by unscrupulous landlords and, more generally, the whims of the consumer society. The final scenes offer an ironic sense of closure, contextualising the film within the current global financial crisis. Director Pang Ho-Cheung has a history of offering satirical depictions of Hong Kong culture through genre films: his first feature film, You Shoot, I Shoot (2001), delivered a blackly comic satire of both Hong Kong’s then-current financial crisis and the decline of Hong Kong cinema in its narrative of a hitman, Bart (Eric Kot), who discovers that it’s increasingly hard to find work due to the sagging economy, and accepts an assassination job which the client (Miao Felin) demands be recorded on film – for which Bart hires the services of out-of-work filmmaker Chuen (Cheung Tat-Ming). From You Shoot, I Shoot to Love in a Puff (2010), Pang’s films also deal sympathetically with the lives of Hong Kong’s young adults and the pressures that face them; and in its focus on Cheng, Dream Home is no exception. It is to both Pang Ho-Cheung and Josie Ho’s credit that Cheng is entirely sympathetic throughout the film: the non-linear narrative structure provides a context for her actions, and having seen Cheng’s childhood and her unfulfilling present, including the pressures of family and day-to-day economics, the viewer can sympathise with her desire to improve her life. There are no known cuts in this DVD release (92:16 mins – PAL). The BBFC have perhapse surprisingly passed the film uncut. This is claimed to be the uncut version rather than the (censored) Hong Kong theatrical version.

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1 (with anamorphic enhancement). The intended theatrical aspect ratio seems to have been 2.35:1, so this is clearly a compromised presentation of the film. The film seems to have been shot on digital video; aside from the graphically violent murder set-pieces, the film contains some strong cinematography: in one scene, as Cheng wanders the city before meeting her lover in the hotel, shots are presented partially out of focus, to signify Cheng’s sense of alienation and her loneliness. In another sequence, after Cheng’s initial attempt to buy the flat is turned down by its current owners (who are asking for a much higher price), an expressionistic device is used to signify Cheng’s sense of her dreams collapsing: she wanders the streets, a SnorriCam (the camera mount famously used in John Frankenheimer’s Seconds, 1968, and Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, 1973) is used, mounted to Josie Ho’s body, as Cheng again wanders the streets.

Audio

The film is presented in its original Cantonese, via a two-channel audiotrack which appears to contain some subtle surround encoding. English subtitles are optional and problem-free.

Extras

Josie Ho Interview (9:39). The actress talks about how she was approached to make the film, her character’s motivation, the fact that the narrative is grounded in the reality of the extreme methods that property developers in Hong Kong used in the 1980s, the director’s claim that the narrative is based on a true event, the choice of music for the film and the recording of the song used in the film, and the choreography of the scenes of violence in the film. Image Gallery (2:08). A series of stills from the production of the film. Theatrical Trailer (1:32). This effective trailer offers a juxtaposition of the film’s quietness and moments of violence. Bonus trailers (6:31) (play on disc startup, skippable) for Tony Manero, No-One Knows About Persian Cats and Afterschool.

Overall

A strong horror film with an interesting structure and no small amount of social relevance, Dream Home is worth investigating. However, it is worth noting that some viewers may find the violence a little too extreme. Nevertheless, unlike other contemporary Category III horror films from Hong Kong (for example, Herman Yau’s Gong Tau, 2007), the scenes of violence in Dream Home are given a strong narrative context. Josie Ho’s performance holds the film together, as she makes Cheng simultaneously frightening and sympathetic; and despite the reputed creative conflicts between Josie Ho and Pang Ho-Cheung, the film has a strong sense of identity, offering a fine balance between its elements of social commentary and the demands of the horror genre. References Fang, Karen, 2004: John Woo’s ‘A Better Tomorrow’. Hong Kong University Press Gelder, Ken, 2000: The Horror Reader. London: Routledge Logan, Bey, 1996: Hong Kong Action Cinema. New York: Overlook Press Williams, Tony, 2000: ‘Hong Kong Social Horror: Tragedy and Farce in Category 3’. In: Schneider, Steven Jay & Williams, Tony (eds), 2000: Horror International. Wayne State University Press: 203-19 For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|