|

|

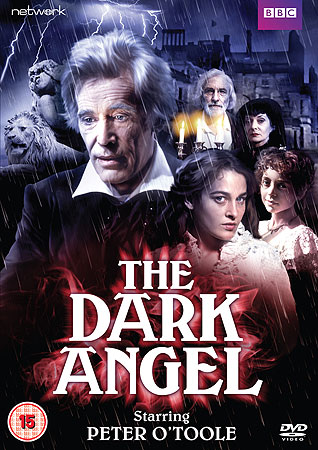

Dark Angel (The) (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (3rd June 2011). |

|

The Show

The Dark Angel (Peter Hammond, 1987)

Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas (1864), originally published in a serial format as ‘Maud Ruthyn and Uncle Silas, A Tale of Bartram-Haugh’, is regarded as one of the best examples of the Victorian Gothic novel. As with several of Le Fanu’s other novels (including Checkmate and The Dark Angel), Uncle Silas derived from an earlier short story, ‘Passage in the Secret History of an Irish Countess’ (1838). In his study of Le Fanu’s work, Michael H Begnal suggests that adapting short stories into novels ‘can occasionally be […] treacherous’, but that ‘extending’ the narrative of Uncle Silas into a novel-length form was ‘instrumental in building the tension’ of the novel (1975: 74). I mention this because this 1987 adaptation of Uncle Silas, produced for television, is the third major adaptation of Le Fanu’s novel, following a 1947 production for Gainsborough, starring Jean Simmons and directed by Charles Frank, and a 1968 adaptation for ITV’s horror-themed anthology series Mystery and Imagination (1966-70). Where the 1947 adaptation took some liberties with the source material, the 1968 version stuck quite faithfully to the novel. This 1987 adaptation retreads pretty much all of the beats of the 1968 version, but with a running time that is almost triple that of the earlier teleplay; despite the presence of some truly great actors (including Peter O’Toole, as the titular Uncle Silas, and Barbara Shelley), this three-part dramatisation of Le Fanu’s novel arguably outstays its welcome and would work better if it were cut down to two hours or so. The narrative follows Maud Ruthyn (played here by Beatie Edney). Living with her father, Austin Ruthyn, Maud has heard many stories about her Uncle Silas but has never met him. ‘Even my mother would not tell me about Uncle Silas’, she declares; ‘Nobody would tell me about him’. Confessing to the housekeeper, Mrs Rusk, that she visualises Silas as ‘a handsome man’, she is told, ‘He was, my dear; Thirty years changes most of us’. Later, she presses her father for information about Silas, his brother. ‘Uncle Silas is a man of great talents, great thoughts, and great wrongs’, Austin tells his daughter. Realising that his daughter lacks female company, Austin hires a governess, Madam de la Rougierre (Jane Lapotaire), who Austin describes to Maud as ‘Someone to take your mama’s place’. However, Maud’s new governess soon proves to have a cruel streak; from the outset, she is presented as a character who has animalistic characteristics, the housekeeper describing her as a woman who ‘eats like a wolf’. Madam de la Rougierre also has a macabre fascination with death, taking Maud to the cemetery and telling her ‘I love to be in a solitary place like this: I’m not afraid of the dead’ before taunting Maud by asking her, ‘What if your father should remarry?’ As the first episode progresses Maud learns that her mysterious Uncle Silas squandered his wealth, leaving his brother Austin to pay his debts. Maud also learns that Silas may have brutally murdered an acquaintance of Austin. When Austin dies suddenly, he leaves his estate to Maud; however, Maud is to be taken into Silas’ care, until she reaches the age of 21. She is sent to live at Silas’ home, Bartram-Haugh. However, if Maud should die, the whole estate will pass to Silas. At Bartram-Haugh, Maud finds Silas to be a mysterious figure, prone to catatonic fits due to his addiction to laudanum. She also meets her two cousins, the quiet Milly and the layabout Dudley (Tim Woodward). When Dudley proposes marriage to Maud, Maud begins to suspect that Silas’ clan may have plans to manoeuvre Austin’s wealth into their hands; Maud begins to find that in the old, decaying Batram-Haugh, her life may be in danger.

As W J McCormack (1993) notes, ‘Uncle Silas tells of damnation, or – to be more correct – it is a tale narrated by one [Maud] who is all but damned by her failure to see spiritual evil in her uncle’ (29). Like many Gothic narratives, Uncle Silas is a story of doppelgangers and doubles: Bartram-Haugh is an inversion of Maud’s father’s house, and Silas himself is an inversion of Maud’s father: ‘the novel advances the implication that’ Bartram-Haugh and Maud’s father’s home ‘differ not on a physical plane, but in their spiritual orientation. Similarly, Uncle Silas is not a character distinct from the narrator’s father: he is the post-mortem state of the father’ (ibid.). Austin suggests as much when he tells his daughter that ‘My brother Silas and I are as different as two brothers can be. All our lives, we have faced in opposing directions and reaped very different rewards. And yet, of late I find we may be closer than I thought [….] And may yet prove two sides of the same coin’. Austin’s death, which precipitates Maud’s movement to Bartram-Haugh and into the care of Silas, is thus the fulcrum of the narrative.

In this version, produced after the era of women’s liberation, Maud’s lack of ability to see her uncle’s deviance strikes the viewer as almost a parody of the naivete of traditional Gothic heroines. This perspective on the traditional Gothic text seems foregrounded when Austin tells his daughter, after she has bothered him with extensive questions about Silas, ‘Curiosity is a vice, and one to which your sex is especially prone’. This adaptation of Uncle Silas’ strengths lie principally in Peter O’Toole’s powerful performance as the mercurial Silas, and in some of the striking nightmare sequences that are located mostly in the second episode. These sequences, drenched in blue, depict Maud’s dreams in an expressionistic manner, recalling the aesthetic of some of the European Gothic horror films of the 1960s and 1970s (especially the work of Mario Bava and Antonio Margheriti).

Episode One (58:20) Episode Two (59:02) Episode Three (57:54)

Video

The Dark Angel is presented in its original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3. Apparently shot entirely on film, on this DVD release The Dark Angel looks good: there are no major issues in terms of the visual presentation of the mini-series.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel stereo track. The volume is a little low at times, but this isn’t too much of a problem. Thankfully, optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

Sadly, there is no contextual material.

Overall

The Dark Angel offers a solid adaptation of Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas. As noted above, its strengths lie largely in its casting and the expressionistic nightmare sequences. However, despite hitting pretty much the same beats from the novel as the 75-minute 1968 adaptation for the series Mystery and Imagination, this three-part dramatisation runs for almost three hours. It ‘sags’ a little in places, but it’s a perfectly serviceable adaptation of the novel that is largely faithful to its source material. References: Begnal, Michael H, 1975: Joseph Sheridan LeFanu. Bucknell University Press McCormack, W J, 1993: Dissolute Characters: Irish History Through Balzac, Sheridan Le Fanu, Years and Bowen. Manchester University Press For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|