|

|

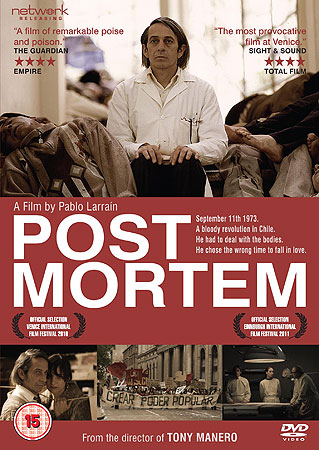

Post Mortem

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (24th January 2012). |

|

The Film

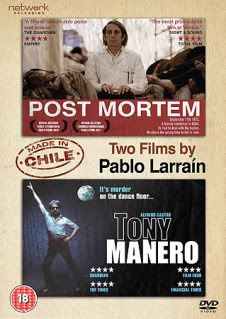

Post Mortem (Pablo Larraín, 2010) Please note that Post Mortem has been released by Network Releasing both separately and as part of a two-disc set entitled Made in Chile: Two Films by Pablo Larraín, accompanied by Larraín’s thematically similar 2008 film Tony Manero.  Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín’s third feature film, Post Mortem (2010) revisits some of the thematic territory of his acclaimed second picture Tony Manero (2008), as well as sharing that film’s leading actor, Alfredo Castro. However, whereas Tony Manero was set four years into the dictatorship of General Pinochet, using its escapist American cinema-obsessed protagonist as a metaphor for the Pinochet regime, Post Mortem is set during the 1973 military coup that left Pinochet in charge of Chile. Through its focus on the lonely and unexceptional civil servant Mario Cornejo (Castro), Post Mortem thus explores the impact of the coup upon the lives of Chile’s citizens.  The film opens with an image from the coup: the camera is slung underneath a halftrack which travels through the litter and debris-strewn streets of Santiago. After this has set the scene, we are taken back to before the coup. Mario is framed looking out of the window of his home. Like Raul in Tony Manero, Mario is introduced as a voyeur, a detached observer of the world around him. Walking through the city, he stops outside the window display of a theatre; the display contains monochrome photographs of women dancing the cancan on stage. Mario enters the theatre and finds its owner, Mr Patricio, complaining that the auditorium is populated by ‘a gang of sex maniacs watching my show’ and suggesting that ‘[t]his is a respectable place’. Mario finds himself ignored as he asks for his ticket whilst the manager complains to the ticket attendant, ‘The problem is that they go behind the seats and masturbate, leaving everything covered with semen’. After buying his ticket, Mario enters the auditorium and watches the show, which is preceded by a crude stand-up comic. When the curtains open and the dancing girls enter the stage, Mario looks increasingly uncomfortable. Eventually, he stands and leaves the auditorium, watching the performance from backstage.  Wandering through the backstage area, Mario spies on Patricio admonishing one of the women, Nancy Puelma (Antonia Zegers), for not looking ‘elegant’ enough. She is the former star of the show, and has been replaced with another, younger, woman. ‘I’m the most elegant thing you’ve ever seen in your life’, Nancy retorts before suggesting that her replacement, Fabiana, was only offered the starring role because she promised the director sexual favours. After Patricio leaves, Mario enters Nancy’s dressing room. She recognises him: Mario and Nancy live across the street from one another. Mario claims to have come to the theatre to congratulate her. In a Dreyer-esque closeup, we see that beneath the fancy clothes and layers of make-up, she is clearly past her prime.  Mario offers to take Elena home. Driving through the streets, they encounter a large group of people holding a demonstration; a banner declares ‘Power to the People’. The demonstration lets the car through; Elena wants to turn around but Mario continues through the crowd before being forced to come to a halt. As they sit motionless in the car, the people in the demonstration surround them and walk past the vehicle, chanting slogans (‘Support the popular government’). Elena sees a man she knows, Victor (Marcelo Alonso). Victor takes Nancy from the car, and she joins the demonstration, which is being held by the Communist Youth of Chile. Mario looks disconcerted.  We are shown Mario at work. He works in a morgue, transcribing autopsies for Dr Castillo (Jaime Vadell) and his assistant Sandra (Amparo Noguera). That evening in Mario’s home, a young boy dictates the handwritten notes that Mario took during the autopsy he observed, and Mario hesitantly types the notes on a traditional manual typewriter. When they finish, the boy asks Mario to pay him. Before the boy leaves, the lonely Mario – who is apparently desperate for human contact – embraces him. At work, Sandra propositions Mario, asking him to ‘stop by my house’ in the evening. ‘I don’t sleep with women who sleep with other men’, Mario tells her after revealing that he knows that one of the doctors ‘stopped by her house the other night’. In the evening, Mario visits Nancy’s home. The boy who dictated Mario’s notes is revealed to be Nancy’s younger brother. Victor answers the door and asks if Mario is there ‘for the meeting’: apparently, the communist group that Victor represents is using Nancy’s home to hold their meetings. Mario waits awhile for Nancy but eventually decides to go home. However, Nancy arrives at Mario’s door and apologises for treating him badly. ‘My house is full of men talking about politics […] None of them want to have a drink with me; that’s bad’, she tells Mario. Nancy is a lapsed Catholic, and she tells Mario how she is afraid of purgatory. She undresses, showing herself to be almost emaciated, and asks Mario, ‘Am I too thin, neighbour?’ Mario cooks eggs for Nancy. As they eat, she cries. Mario is unsure how to react, but eventually he begins to weep too. They sleep together, and later walk through the streets of Santiago together. They visit a Chinese restaurant, where Nancy makes snide and spiteful remarks about Chinese communist culture to the waitress. Mario proposes to Nancy, but in response she asks him ‘What was your name again, neighbour?’ before enquiring about what he does for a living. Mario tells Nancy that he’s a ‘civil servant’, but he refrains from informing her that he transcribes autopsies.  Mario visits the theatre where Nancy works and tries to tell Patricio that ‘Nancy is a great artist. Her presence is fundamental for the show’. ‘Do I look like a girl?’, Patricio asks: ‘Then why do you want to fuck me, man?’ Mario commits an act of vandalism, to which Patricio responds by offering to keep Nancy on the stage if Mario gives him his car. Besotted by Nancy, Mario agrees. Whilst showering one day, Mario hears shouting and an explosion. He goes to investigate and finds Nancy’s house torn apart. Taking the car from in front of the house, he drives through the streets and finds them in ruin. Passing the theatre, he sees the red car he gave to Patricio destroyed, along with several other cars. Arriving at work, he finds armed soldiers in the corridors. The soldiers interview Sandra, Dr Castillo and Mario. Dr Castillo tells Sandra that a state of war has been declared, and soon the hospital will be full.  Mario tries futilely to track down Nancy. Outside the hospital, he sees dead and injured people being unloaded from trucks. Soon, Castillo, Mario and Sandra are led away by the troops. Mario is told, ‘Mr Cornejo. Congratulations, you now serve the Chilean army’. Castillo is to perform autopsies on dead troops, watched by soldiers from the new Chilean army. Mario is ordered to take notes on an electric typewriter. However, he struggles to keep up, being used to handwriting his notes. He is replaced by a soldier who can type. Meanwhile, Sandra refuses to perform the internal examination and goes to stand by Mario, leaving Castillo by himself. After this, in his commentary over the autopsy Castillo reveals the corpse to be that of Salvador Allende Gossens, the Marxist president of Chile until the military coup of 1973 that left Pinochet in power. Allende committed suicide, as suggested by Castillo in the film; but there has been persistent suggestion that he was assassinated. (An inquiry in Allende’s death was opened on January 11, 2011, not long after this film was released.) Returning home, Mario finds Nancy in the debris of her former home. He presses her for an answer to his question as to whether she will marry him, but she refuses to give him a response. Nevertheless, she kisses him tenderly. Over the next few days, Mario cares for Nancy, who hides in the rubble of her house. He brings her a radio, but she asserts that she needs one with batteries. She also demands that he find her father and brother. Meanwhile, with each day the number of dead multiply until one day the hospital stairwell is filled with bodies. Sandra begins to break down when she recognises two of the bodies as being a nurse and one of her patients who she had previously saved. She demands to know what happened to them. ‘I saved him. You killed him again!’, she screams.  One day, Mario calls at Nancy’s hideout and finds her sleeping with Victor. Victor asks him to bring them some more food. Mario agrees. Nancy notices how heartbroken Mario is, and seemingly attempting to pacify and placate him, she masturbates him before telling him to ‘Bring me cigarettes, neighbour’. Tired of being taken for a patsy, Mario waits until Nancy and Victor are settled in their hideaway before blocking the door with debris, effectively murdering the pair. In the British Film Institute-published monograph on Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (published as part of the BFI’s Modern Classics range), Australian critic Adrian Martin suggested that Noodles (Robert De Niro), the anti-hero of Leone’s film, is a voyeuristic ‘sleepwalker’ – for Martin, a recurring character type in modern cinema: ‘Noodles’ vision, his male gaze […] orders nothing, effects nothing. When he looks longingly across a distance, his gaze marks only that distance, and the unbridgeable emotional abyss which it represents. And, more profoundly, he is one of the archetypal male sleepwalkers of modern cinema, a ghost or zombie on par with Willem Dafoe in Light Sleeper (Paul Schrader, 1991) or Jack Nicholson in The Crossing Guard (Sean Penn, 1995). This is the meaning and resonance of the line when, on his faithful return to the bar, Noodles replies to Moe’s question about what he has been doing since 1933 with five little words that speak volumes: “Been goin’ to bed early”’ (Martin, 1998: 56).  Like the protagonist of Tony Manero, Raul Peralta, Mario could be classed as one of Martin’s ‘sleepwalkers’: like Raul, Mario lives his life as a detached observer of the world around him, and also like Raul he is largely emotionless. However, where Raul is a psychopath who is prone to outbursts of unconscionable violence, Mario’s lack of emotional response seems to be a product of repression. His boyish pageboy haircut, tinged with grey, denotes him as almost childlike. In an uncomfortable scene filmed in a voyeuristic long take, when Nancy and Mario eat together Nancy begins to cry; after a while, as if the floodgates have been opened by Nancy’s expression of emotion, the repressed Mario begins to sob uncontrollably too. Like Martin’s ‘sleepwalkers’, throughout Post Mortem Mario lives a liminal existence, barely noticed by others until the neurotic Nancy, desperate for attention, turns towards him: during the scene in which he attempts to buy a ticket for the show that Nancy is appearing in, he struggles to be heard as Patricio and the ticket booth attendant discuss the ‘gang of perverts’ that Patricio claims are paying to see the show. Mario also compromises throughout the entire film: he is passive and unable (or unwilling) to take a stand – against Nancy, who exploits Mario’s goodwill; against Patricio, who demands that Mario gives him his car in exchange for continuing to provide Nancy with work; and especially against Victor, who whisks Nancy away from Mario at the demonstration. Hints of violence and perversion drip subtly throughout the film, climaxing with the coup. Little to no violence is shown onscreen, the coup taking place offscreen, but its effects are felt throughout the film. The opening shot features the camera slung under a halftrack that is travelling through the debris-strewn streets of Santiago, and in a later sequence, Mario is asked to transcribe the autopsy of a woman who has been brutally beaten to death. The film also alludes to an undercurrent of perverse sexuality which never surfaces overtly: the object of Mario’s affections, Nancy’s emaciated body is perhaps beautiful to Mario precisely because it isn’t ‘perfect’, but it also makes Nancy seem childlike. Furthermore, in a series of consecutive scenes, we see: Mario taking notes on the autopsy of Nancy – who seems to have died due to malnutrition – before helping to lift her naked body from the table (this scene appears to be a fantasy, as it has no narrative function, and in the film’s diegesis the character of Nancy survives to the climax); then we see Mario with Nancy’s younger brother who is dictating the autopsy notes to Mario as he types them before embracing the boy; and finally we see Mario masturbating alone in his home.  For most of the film, Nancy and Mario struggle to avoid engagement with politics – during the sequence in which the pair approach the demonstration by the Communist Youth of Chile, Nancy implores Mario to turn back – but with the coup, they are forced to cope with the impact of realpolitik on their lives. Despite living with her politically-engaged father and having an affair with the strongly political Victor, both of whom are associated with the communist movement, Nancy verbally abuses the communist ideology of China during her and Mario’s nighttime visit to a Chinese restaurant. After the coup, she is forced to go into hiding due to her associations with both her father and Victor, whose left wing views have led to their persecution by the new military regime. On the other hand, during lunch Castillo expresses communist sympathies, suggesting that ‘Nobody can escape from the Wheel of History’ and arguing that people (‘cells, social organisations, neighbourhood associations’) should all be armed as this is how ‘the Vietnamese taught us to fight’ and how ‘Ho Chi Minh defeated an empire’. However, when faced with the new military regime, Castillo rapidly abandons his communist sympathies. He initially becomes the new regime’s meek servant, but eventually transforms into its enforcer: at one point, he threatens Sandra with a gun after she becomes almost hysterical on noticing that one of the hospital’s nurses and a patient who Sandra previously saved are amongst the dead bodies that litter the entrance to the hospital. Larraín seems to be suggesting that the political apathy of Chilean citizens like Mario led to a passive acceptance of the coup, and that the new regime easily won the consent of a fickle and politically disengaged populace. In fact, for his passive complicity in the coup Larraín has compared Mario to Clerici, the protagonist in Bernardo Bertolucci’s Il conformista (The Conformist, 1970), who simply through his desire to conform and be seen as ‘normal’ becomes a tool of fascist ideology (see Matheou, 2011). The film runs for 93:33 mins (PAL).

Video

Shot on 16mm film (with an anamorphic lens) and blown up to 35mm, Post Mortem is here presented in a very wide aspect ratio of 2.75:1 – with anamorphic enhancement. The transfer is clean and unproblematic. The use of 16mm film adds an almost documentary-like naturalism to the mise-en-scene. Larraín also uses off-centre compositions that encourage the viewer to reflect on how the image is composed and what lies offscreen. The screen is dominated by drab colours (browns, greys) that reflect the repressive outlook of the film’s protagonist. Larraín and his cinematographer (Sergio Armstrong) attempted to emulate the aesthetic of 1970s films, and to this end they used anamorphic Lomo lenses that had originally been used by Tarkovsky in the late-1960s. As Larraín has declared, ‘They were old, fucked-up and really hard to use — if you touched them, they’d crumble. But they were great. People think we spent ages in post-production to get that pale image, but our whole “technique” was not to do anything’ (Matheou, op cit.).

Audio

Audio is offered in a choice of a Dolby Digital 5.1 track or a two-channel Dolby Digital stereo track. English subtitles are optional. The 5.1 track has some subtle surround encoding: it’s not showy but is very effective at times. For example, in a scene that depicts Mario in his home during the evening, the rear channels are used for a very immersive wind effect that communicates the cold, miserable weather outside. The stereo track is clean and functional, but the 5.1 track is the best way to watch the picture.

Extras

The disc includes a documentary, ‘Behind Post Mortem’ (31:38) (in Spanish, with optional English subtitles). This documentary opens with mages of the coup and a discussion of the effects of the coup on Chilean society. It situates the film within its social context, and also gives glimpses of the production of the film, and features interviews with Larraín and the principal actors (Zeger, Noguera, Castro), who talk extensively about the characters they play. Larraín also talks about the importance of voyeurism to this film, which is intended to ‘give a strangeness’ to the character Castro plays. Also included are a gallery of images from the film (1:00) and the film’s trailer (1:57). Bonus trailers (playable on start-up and skippable) are included: Tony Manero, Circo, The Peddler.

Overall

Post Mortem features a similarly passive protagonist to Larraín’s second film Tony Manero, and like its predecessor Post Mortem also benefits from an equally strong performance by Alfredo Castro. Larraín has said that these two films form the first two instalments in a proposed trilogy of films about the Pinochet regime. The narrative of Post Mortem is a little disconnected in places; this may have been Larraín’s intent, but until the sequence depicting the coup the film is little more than a series of tableaux with little narrative structure – perhaps reflecting Mario’s piecemeal, disengaged perception of the world around him. This may alienate some viewers; but Castro’s performance as Mario is gripping. Perhaps surprisingly, Mario is based on a real man whose identity Larraín uncovered during his research into the coup: referring to Salvador Allende’s autopsy, Larraín has said that ‘For me, it’s the autopsy of Chile. The report is signed by three people. Two of them are very well-known doctors, but the third, a guy called Mario Cornejo, was unknown. I thought, “Who is this guy?” We did some research and found out that he was the coroner’s assistant. He’s dead now, but we got in touch with his family, and I met his son, who actually does the same job as his father [….] I realised that his could be a very interesting point of view, this guy backstage; nobody knows him, nobody cares about him, but he was there. Sometimes very ordinary people, people who are invisible in society, get to be at these momentous moments in history. I wanted to see what happened through those eyes’ (Matheou, op cit.). Much research has apparently gone into the production this film, and it shows. Larraín has suggested that he hopes someday to make the final part of his ‘trilogy’ about the Pinochet era: a film focusing on Pinochet himself. With luck, this project will come to pass. References: Martin, Adrian, 1998: BFI Modern Classics: ‘Once Upon a Time in America’. London: British Film Institute Matheou, Demetrios, 2011: ‘The Body Politic: Pablo Larraín on Post Mortem’. [Online.] http://www.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/featuresandinterviews/interviews/pablo-Larraín-post-mortem.php For more information, please visit the homepage of Network. This review has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|