|

|

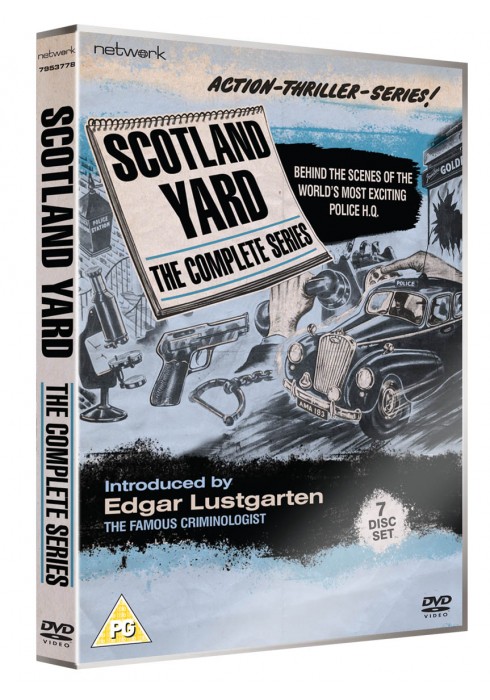

Scotland Yard: The Complete Series

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th January 2013). |

|

The Film

Scotland Yard: The Complete Series

In Beyond Dixon of Dock Green: Early British Police Series (2002), Susan Sydney-Smith suggests that by the mid-1960s ‘the Scotland Yard series [ie, programmes focusing on the activity of Scotland Yard detectives] constituted a television genre in its own terms’ and became a forerunner of some of the more aggressive police series of the 1970s, including The Sweeney (Thames, 1975-8) (143). The first onscreen depictions of the activities of Scotland Yard were, according to Sydney-Smith, ‘a series of 15-minute dramatisations called “Telecrimes” [BBC, 1938-46], where a Scotland Yard inspector would introduce true crimes from the casebook’ (ibid.: 18). These early ‘productions contain documentary realism, in that they are concerned to show a degree of procedural activity, but are not yet concerned with the ambiguities of day-to-day police procedure’ (ibid.). However, Sydney-Smith states that television series which focused on investigative work carried out by Scotland Yard detectives derived to a large extent from ‘the Scotland Yard 3-reeler “B” movies, particularly those made by Merton Park and narrated by the British journalist Edgar Lustgarten’ (ibid.). Many subsequent police series, including the Scotland Yard ‘B’ features under discussion here (also known as Case Histories of Scotland Yard), followed the format of Telecrimes: dramatised re-enactments of noteworthy cases, introduced by a figure of authority, and focusing on specific aspects of police procedure. Originally produced for cinema exhibition (as ‘B’ features) and distributed in cinemas by Anglo-Amalgamated Film Distributors between 1953 and 1961, the 39 stories included in this collection found a wider audience when shown on television under the Scotland Yard banner. Filmed at Merton Park Studios, each instalment was based on a true crime. Some of the crimes are now largely forgotten, whilst others are still well-remembered: for example, the first instalment, ‘The Drayton Case’, features a 1944 crime which has been covered fairly recently in an ITV documentary – the attempt by a man, Charles Drayton, to hide the body of his murdered wife in the cellar of the schoolhouse in which he worked as a caretaker, only for the skeletonised body to be unearthed following a bombing raid by German aircraft. The majority of the crimes depicted in the episodes are shown as taking place in the late-1930s or within recent memory at the time that these stories would be shown in cinemas, during the 1950s – and to some extent, the series could be accused of sensationalism due to this.    The episodes begin with a shot of a police car travelling through city streets. Over this, the opening titles of each episode play out in white text, the specific episode title prefaced by the onscreen declaration, ‘a dramatised adaptation of one of the many crimes investigated by the most celebrated police centre in the world’. On the soundtrack dramatic music (‘Mailed Fist’, by Cecil Milner) segues into equally dramatic narration: ‘Scotland Yard, nerve centre of London’s Metropolitan Police; headquarters of its Department of Criminal Investigation. Scotland Yard, a name that appears on almost every page of the annals of crime detection. Scotland Yard, where night and day a determined body of men carry on a relentless, unceasing crusade against crime’. Under this narration, we are presented with a montage of images showing police work within Scotland Yard: a 1950s police control room in which one officer uses a magnifying glass to precisely position a marker on a map; an archive room in which men are shown carefully examining documents and fingerprint records; a shot of a door which carries a sign reading ‘Records Dept’. The camera slowly dollies in to the sign, and the door opens slowly. ‘Stored deep in the heart of Scotland Yard are the records of thousands of cases’, the narrator tells us, ‘histories of every breach of the law from larceny to murder. Here are stories of human weakness, of greed and envy, of cunning and stupidity’. In the Records Department, binders line shelves which run the length of each wall. The camera slowly and deliberately dollies into one specific binder; on its side is written the name of the victim of the story depicted within the episode and, beneath the name, the year of the crime. A hand reaches out for the binder… From ‘Murder Anonymous’ (episode 14) onwards, this introductory sequence changes slightly. These later episode are introduced by shots of London accompanied by the sound of Big Ben’s chimes. A narrator intones, ‘In the heart of London, a few yards from Downing Street, a stone’s throw from the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey, is the building which houses the key men of the most famous police force in the world: Scotland Yard’. (The final few episodes feature a slightly different version of this introduction: ‘London, greatest city of the world and home of the oldest democracy, a city whose worldwide reputation for honesty and integrity is firmly based on a thousand years of the rule of law, enforced and safeguarded by a police force whose headquarters is as well known as London itself: Scotland Yard’.) The episodes begin with a shot of a police car travelling through city streets. Over this, the opening titles of each episode play out in white text, the specific episode title prefaced by the onscreen declaration, ‘a dramatised adaptation of one of the many crimes investigated by the most celebrated police centre in the world’. On the soundtrack dramatic music (‘Mailed Fist’, by Cecil Milner) segues into equally dramatic narration: ‘Scotland Yard, nerve centre of London’s Metropolitan Police; headquarters of its Department of Criminal Investigation. Scotland Yard, a name that appears on almost every page of the annals of crime detection. Scotland Yard, where night and day a determined body of men carry on a relentless, unceasing crusade against crime’. Under this narration, we are presented with a montage of images showing police work within Scotland Yard: a 1950s police control room in which one officer uses a magnifying glass to precisely position a marker on a map; an archive room in which men are shown carefully examining documents and fingerprint records; a shot of a door which carries a sign reading ‘Records Dept’. The camera slowly dollies in to the sign, and the door opens slowly. ‘Stored deep in the heart of Scotland Yard are the records of thousands of cases’, the narrator tells us, ‘histories of every breach of the law from larceny to murder. Here are stories of human weakness, of greed and envy, of cunning and stupidity’. In the Records Department, binders line shelves which run the length of each wall. The camera slowly and deliberately dollies into one specific binder; on its side is written the name of the victim of the story depicted within the episode and, beneath the name, the year of the crime. A hand reaches out for the binder… From ‘Murder Anonymous’ (episode 14) onwards, this introductory sequence changes slightly. These later episode are introduced by shots of London accompanied by the sound of Big Ben’s chimes. A narrator intones, ‘In the heart of London, a few yards from Downing Street, a stone’s throw from the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey, is the building which houses the key men of the most famous police force in the world: Scotland Yard’. (The final few episodes feature a slightly different version of this introduction: ‘London, greatest city of the world and home of the oldest democracy, a city whose worldwide reputation for honesty and integrity is firmly based on a thousand years of the rule of law, enforced and safeguarded by a police force whose headquarters is as well known as London itself: Scotland Yard’.)

Following a dissolve, we are presented with a scene of Edgar Lustgarten (‘famous both as novelist and broadcaster, and one of the world’s foremost authorities on both criminals and crime’), in a quaint old-fashioned office decorated with an oak desk, a drinks cabinet (from which Lustgarten often pours a drink whilst addressing the audience) and a leather armchair. Lustgarten’s introductions here – with the setting and Lustgarten’s delivery connoting a now antiquated form of patriarchal authority – were closely parodied through the character of the Criminologist in Richard O’Brien’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show, played by Charles Gray in Jim Sharman’s 1976 film adaptation – who introduced Brad and Janet’s story from a similarly quaint setting. (Scotland Yard itself was also parodied closely in LWT’s The Robbie Coltrane Special from 1989.) These two tiers of narration act as the gatekeepers of each entry into this series. Lustgarten’s presence is established visually and orally, bookending each narrative and foregrounding its message at the beginning and end of each story – much like Rod Serling’s introductions to the episodes within The Twilight Zone (CBS, 1959-64) or Alfred Hitchcock’s dry presentations within each episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents/The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (Revue Studios/Universal, 1955-65). Lustgarten’s delivery is authoritative and somewhat comforting, slightly mitigating the dark and brutal nature of some of the crimes detailed in the episodes.  In his introductions, Lustgarten addresses the viewer directly, often presenting us with rhetorical questions. In ‘The Drayton Case’, for example, Lustgarten asks us, ‘Have you ever murdered anyone? Perhaps you’d rather not say. Whether you have or not, you will appreciate this: one of the major problems that confronts a murderer is, what do you do with the body?’ Lustgarten’s narration intrudes throughout the episodes: it is not limited to the opening and closing sequence of each story, but appears throughout the narrative, and often there are cutaways to Lusgarten sitting in his office. This technique, derived from Telecrimes, gives the series a documentary-like aesthetic, and to some extent Scotland Yard could be labelled a drama documentary. However, there is, of course, heavy fictionalisation within the episodes. For example, ‘The Missing Man’ focuses on a retired vicar, John Neil, and his wife, who arrive in London and find that their son Gerald, a young engineer, has gone missing. However, Mrs Neil has a vivid dream, which is shown to the viewer in an expressionistic manner – shot in negative, we are presented with Mrs Neil’s nightmare which involves a tree that ‘seemed to bring with it an intense feeling of foreboding’, and a ruined farm through which her son Gerald is seen walking. We are told by Lustgarten that Mrs Neil’s ‘sense of evil suddenly became a feeling of terror’ focused on a well located within the farm. The sequence is creepy and nightmarish, like a sequence from a 1930s horror film. In his introductions, Lustgarten addresses the viewer directly, often presenting us with rhetorical questions. In ‘The Drayton Case’, for example, Lustgarten asks us, ‘Have you ever murdered anyone? Perhaps you’d rather not say. Whether you have or not, you will appreciate this: one of the major problems that confronts a murderer is, what do you do with the body?’ Lustgarten’s narration intrudes throughout the episodes: it is not limited to the opening and closing sequence of each story, but appears throughout the narrative, and often there are cutaways to Lusgarten sitting in his office. This technique, derived from Telecrimes, gives the series a documentary-like aesthetic, and to some extent Scotland Yard could be labelled a drama documentary. However, there is, of course, heavy fictionalisation within the episodes. For example, ‘The Missing Man’ focuses on a retired vicar, John Neil, and his wife, who arrive in London and find that their son Gerald, a young engineer, has gone missing. However, Mrs Neil has a vivid dream, which is shown to the viewer in an expressionistic manner – shot in negative, we are presented with Mrs Neil’s nightmare which involves a tree that ‘seemed to bring with it an intense feeling of foreboding’, and a ruined farm through which her son Gerald is seen walking. We are told by Lustgarten that Mrs Neil’s ‘sense of evil suddenly became a feeling of terror’ focused on a well located within the farm. The sequence is creepy and nightmarish, like a sequence from a 1930s horror film.

The majority of the episodes provide a detailed focus on police procedure. Ernest Cashmore (1994) has argued that in the late-1950s and 1960s, both UK and US television featured an ‘emphasis on detection, as opposed to policing’, foregrounding narratives that focused on ‘[d]etectives, plainclothes or uniformed, institutional or private’ (158). Cashmore points to Scotland Yard as a key series in the popularisation of stories about detectives: ‘[i]t allowed the viewer to trace the course of detection, aided by narrator Edgar Lustgarten’ (ibid.). Cashmore suggests that along with Z Cars (BBC, 1962-78) and No Hiding Place (Associated-Rediffusion, 1959-67), Scotland Yard ‘relied on the documentary traditions of British cinema in the 1930s. They [these series] were grainy and unglamorous; part of their effort was to remain plausible, in contrast to their US counterparts whose exotic locations and fanciful plots made them fantasies rather than believable accounts’ (ibid.: 159). The drama documentary-style presentation and focus on police procedural elements allies Scotland Yard with some of the American post-war ‘semi-documentary’ films noirs, including The House on 92nd Street (Henry Hathaway, 1945) and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City (1948). The documentary-style approach of American post-war films noirs are said to have been shaped by the conventions of both Italian neo-realism and wartime newsreels: Brian McDonnell has stated that one of the ‘effect[s of wartime social developments was to encourage a general move toward greater realism in film and in particular to foster the use of documentary techniques in fictional feature films. Americans had become used, during the war, to watching extended newsreels and documentaries made in support of the war effort. They were both accustomed to the strident voice-overs of these nonfiction films and had become more inured to the brutality of war violence. All these developments led to what has been labeled the semidocumentary subgenre of classical noir’ (2007: 79). Although McDonnell’s comments are focused specifically on American films noirs, they are equally applicable to British series such as Scotland Yard – which likewise seems to be shaped, at least in part, by the conventions of wartime newsreels. In fact, the first instalment (‘The Drayton Case’) takes place during the last years of the Second World War, when Mrs Drayton’s skeleton is uncovered after a German bombing run over London; and Lustgarten tells us that even during the Blitz, ‘every bomb victim was subjected to a very careful medical examination. The cause of death had to be determined, in order to make quite sure whether the murderer was one Adolf Hitler, or whether it was a murder by a person or persons unknown’.   Other parallels may be drawn between Scotland Yard and American films noirs. Aside from the semi-documentary approach outlined above, a significant number of episodes feature similar low-light photography (and expressionistic use of light and shadow) and location shooting to American films noirs. Set in 1952, ‘The Dark Stairway’ is one of the most overtly noir-tinged episodes, featuring a murder that takes place in the darkened stairway of a tenement building, with the arrival of five suspects in the murder shown in noirish chiaroscuro lighting and fragmented montage. In this episode, the murder is solved by a detective who trawls through dingy nightclubs; the exploration of the underbelly of the city is yet another aspect that recalls American films noirs. As with roughly contemporaneous American noir pictures such as On Dangerous Ground (Nicholas Ray, 1952) and Where the Sidewalk Ends (Otto Preminger, 1950), this episode (and a number of others) depict policing less as a form of pastoral care (as per Dixon of Dock Green; BBC, 1955-76) and more as a seemingly vain attempt to hold back a rising tide of violence. Many episodes offer a detailed examination of police procedure that will be familiar even to today’s viewers of quickly-paced television procedurals such as the BBC’s Silent Witness (1996- ) or the hugely-popular US import CSI: Crime Scene Investigation (CBS, 2000- ). For example, ‘The Candlelight Murder’ focuses on the death of an elderly man in a Sussex village during the late-1930s. The police note that the man’s face has been deliberately mutilated ‘to make identification difficult’. Much of the episode is taken up with detailed examination of the forensic techniques used to solve the crime, including a reconstruction of the man’s face and the use of a cast of a footprint found at the scene to identify a potential suspect. Cynicism towards using these new methods of forensic science to solve crimes is expressed through the character of a cobbler to whom a policeman takes the cast with the hope of identifying the type of shoe worn by the killer. It is a snappy, procedure-laden episode that contains detailed montages of forensic techniques which will be familiar to any viewer of modern forensic dramas.   Other episodes offer a slightly different perspective on the crimes they depict. ‘Blazing Caravan’ is heavily focalised through the perspective of the criminal, with Lustgarten’s narration offering insight into the murderer’s thinking. The narration in this episode is slightly chatty and informal, sometimes addressing the viewer in the second person as if s/he was the criminal: revealing that the victim was a taxidermist, Lustgarten intones, ‘Fancy living in that house with all those stuffed animals - enough to give you the creeps. Still, he was always amiable enough. He was amiable that day you called. In fact, amiable’s hardly the word. Delirious would be more like it’. Disc One: ‘The Drayton Case’ (24:47) ‘The Missing Man’ (29:31) ‘The Candlelight Murder’ (31:24) ‘The Blazing Caravan’ (31:46) ‘The Dark Stairway’ (31:32) ‘Late Night Final’ (28:31) Disc Two: ‘Fatal Journey’ (30:08) ‘The Strange Case of Blondie’ (31:52) ‘The Silent Witness’ (31:50) ‘Passenger to Tokyo’ (31:14) ‘Night Plane to Amsterdam’ (30:34) ‘The Stateless Man’ (28:36) Disc Three: ‘The Mysterious Bullet’ (31:09) ‘Murder Anonymous’ (31:58) ‘The Wall of Death’ (30:22) ‘The Case of the River Morgue’ (32:16) ‘Destination Death’ (31:41) ‘Person Unknown’ (31:47) Disc Four: ‘The Lonely House’ (32:14) ‘Bullet from the Past’ (31:46) ‘Inside Information’ (30:40) ‘The Case of the Smiling Widow’ (31:33) ‘The Mail Van Murder’ (29:10) ‘The Tyburn Case’ (32:24) Disc Five: ‘The White Cliffs Mystery’ (32:20) ‘Night Crossing’ (31:50) ‘Print of Death’ (26:46) ‘Crime of Honour’ (26:46) ‘The Cross-Road Gallows’ (28:17) ‘The Unseeing Eye’ (27:39) Disc Six: ‘The Ghost Train Murder’ (31:19) ‘The Dover Road Mystery’ (29:05) ‘The Last Train’ (31:52) ‘Evidence in Concrete’ (28:03) ‘The Silent Weapon’ (27:18) ‘The Grand Junction Case’ (26:48) Disc Seven: ‘The Never Never Murder’ (29:46) ‘Wings of Death’ (27:41) ‘The Square Mile Murder’ (27:39) Image Gallery (5:15)

Video

Shot on monochrome 35mm film, the stories are presented in their original aspect ratios. The episodes on the first five discs are presented in the traditional 4:3 screen ratio, whilst the episodes on discs six and seven (from ‘The Ghost Train Murder’ onwards) are presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1, with anamorphic enhancement (on these episodes, the image is slightly pillarboxed). Each episode is preceded by the StudioCanal logo (28s) and, if you immediately rewind each title as it starts, you will find a hidden ‘Easter egg’ in the form of each instalment’s original BBFC certificate (all of which are onscreen for roughly 10s).

The episodes are all in surprisingly good shape, with some expected wear and tear evident from time to time. For the most part, the monochrome image has clarity and definition, and contrast levels are good: the early episodes are more expressionistic in their use of lighting, and in this regard their presentation on this DVD set is strong. Later instalments have a slightly less visually dramatic lighting plan – more televisual than cinematic, despite the fact that these later episodes immediately appear more cinematic due to the fact that they are presented in a widescreen format.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is clear throughout the episodes but based on clearly degraded materials, and some episodes have an audible background hiss. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

Image Gallery (disc seven): posters and promotional artwork for the episodes shown in UK cinemas: ‘The Drayton Case’, ‘The Blazing Caravan’, ‘Late Night Final’, ‘The Strange Case of Blondie’, ‘Fatal Journey’, ‘The Silent Witness’, ‘Passenger to Tokyo’, ‘Night Plane to Amsterdam’, ‘The Stateless Man’, ‘The Mysterious Bullet’, ‘Murder Anonymous’, ‘Destination Death’, ‘Person Unknown’, ‘The Lonely House’, ‘Bullet from the Past’, ‘Inside Information’, ‘The Case of the Smiling Widow’, ‘The Mail Van Murder’, ‘The Tyburn Case’, ‘The White Cliffs Mystery’, ‘Night Crossing’, ‘Print of Death’, ‘The Cross Road Gallows’, ‘The Unseeing Eye’, ‘The Ghost Train Murder’, ‘The Dover Road Mystery’, ‘The Last Train’, ‘Evidence in Concrete’, ‘The Silent Weapon’, ‘The Grand Junction Case’, ‘The Never Never Murder’, ‘Wings of Death’ and ‘The Square Mile Murder’.

Overall

Filled with familiar faces (John Le Mesurier, Roger Delgado, Harry H Corbett, Jill Ireland), the episodes of Scotland Yard are for the most part fascinating and hugely entertaining, despite Susan Sydney-Smith’s assertion that the titles of the episodes ‘were often the most exciting aspect of these unremittingly middle-class productions’ (op cit.: 143). The half hour format ensures that the instalments move along at a snappy pace, and as noted above the episodes take a variety of approaches to their subject matter – although, it has to be said, the majority of the episodes take the form of a police procedural, with instalments such as the criminal-focused ‘Blazing Caravan’ being the exception rather than the rule. The structure of the procedural episodes will be familiar to viewers of modern police procedurals, and some of the crimes are still firmly lodged in the public’s subconscious.  Made for cinema exhibition as ‘B’ features before finding another audience on television under the Scotland Yard title, these episodes also benefit from being shot on 35mm film, at a time when much television programming was increasingly being shot on videotape. Film can handle contrast much more efficiently than videotape, and as noted above quite a few of these episodes feature a film noir-esque aesthetic dominated by high contrast photography and chiaroscuro lighting. Consequently, many of these episodes have an aesthetic that compares favourably with the visual style of American films noirs made for cinema exhibition. The presentation of the episodes on this DVD set is also commendable: although wear and tear is evident here and there, the instalments are in remarkably good shape – and the set includes the episode ‘Wall of Death’, which collectors of the series have previously struggled to obtain. Made for cinema exhibition as ‘B’ features before finding another audience on television under the Scotland Yard title, these episodes also benefit from being shot on 35mm film, at a time when much television programming was increasingly being shot on videotape. Film can handle contrast much more efficiently than videotape, and as noted above quite a few of these episodes feature a film noir-esque aesthetic dominated by high contrast photography and chiaroscuro lighting. Consequently, many of these episodes have an aesthetic that compares favourably with the visual style of American films noirs made for cinema exhibition. The presentation of the episodes on this DVD set is also commendable: although wear and tear is evident here and there, the instalments are in remarkably good shape – and the set includes the episode ‘Wall of Death’, which collectors of the series have previously struggled to obtain.

In sum, this is a very good release of an interesting and exciting series, mitigated very slightly by the lack of any contextual material other than the image galleries noted above. References: Cashmore, Ernest, 1994: And There Was Television. London: Routledge McDonnell, Brian, 2007: ‘Film Noir Style’. In: Mayer, Geoff & McDonnell, Brian (eds) 2007: Encyclopedia of Film Noir. Connecticut: Greenwood Press: 70-84 Murphy, Robert, 2007: ‘British Film Noir’. In: Spicer, Andrew (ed), 2007: European Film Noir. Manchester University Press: 84-111 Sydney-Smith, Susan, 2002: Beyond Dixon of Dock Green: Early British Police Series. London: I B Tauris This release has been kindly sponsored by:

|

|||||

|