|

|

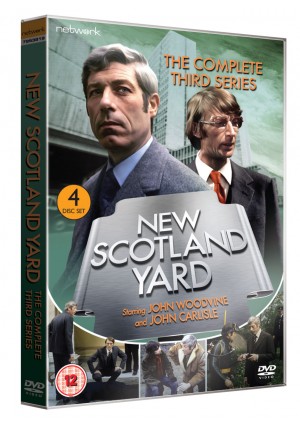

New Scotland Yard: The Complete Third Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th September 2013). |

|

The Show

New Scotland Yard: The Complete Third Series (LWT, 1973)  Described on the BFI’s ScreenOnline web resource as ‘barely remembered’, New Scotland Yard (LWT, 1972-4) was part of a group of early-1970s crime dramas that interrogated ideas about ‘traditional’ police methods (Delaney, 2003: np). Sean Delaney claims that ‘the first of this wave’ was Euston Film’s action-oriented revamp of Special Branch (Thames 1973-4), and this era of police drama would find its most popular expression in The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) (ibid.). To some extent, these series drew on the depiction of anti-establishment policemen in American films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971). A direct forerunner of The Sweeney, New Scotland Yard was originally broadcast alongside the newer, more action-oriented incarnation of Special Branch: where the first series of the reinvented Special Branch was scheduled on a Wednesday evening (with the second series being moved to a Thursday), New Scotland Yard was broadcast on a Saturday. As with Special Branch, the opening titles sequence of New Scotland Yard establishes it as a fast-paced, hard-hitting series: via rapid montage and what are almost ‘smash cuts’, we are shown the iconic scenery of London as police vehicles travel along its roads. All of this is accompanied by exciting, slightly aggressive music. Described on the BFI’s ScreenOnline web resource as ‘barely remembered’, New Scotland Yard (LWT, 1972-4) was part of a group of early-1970s crime dramas that interrogated ideas about ‘traditional’ police methods (Delaney, 2003: np). Sean Delaney claims that ‘the first of this wave’ was Euston Film’s action-oriented revamp of Special Branch (Thames 1973-4), and this era of police drama would find its most popular expression in The Sweeney (Thames, 1974-8) (ibid.). To some extent, these series drew on the depiction of anti-establishment policemen in American films such as The French Connection (William Friedkin, 1971) and Dirty Harry (Don Siegel, 1971). A direct forerunner of The Sweeney, New Scotland Yard was originally broadcast alongside the newer, more action-oriented incarnation of Special Branch: where the first series of the reinvented Special Branch was scheduled on a Wednesday evening (with the second series being moved to a Thursday), New Scotland Yard was broadcast on a Saturday. As with Special Branch, the opening titles sequence of New Scotland Yard establishes it as a fast-paced, hard-hitting series: via rapid montage and what are almost ‘smash cuts’, we are shown the iconic scenery of London as police vehicles travel along its roads. All of this is accompanied by exciting, slightly aggressive music.

Traditionally, in British television drama police work was shown as a form of pastoral care, with the uniformed community policeman depicted as a friendly, paternal figure – as in Dixon of Dock Green (BBC, 1955-76). However, during the late 1960s and 1970s programmes increasingly began to focus on non-uniformed police who were willing to bend the rules as a means of negotiating the fine line between law and disorder. An influential 1994 essay on the representation of policing on British television (‘The dialectics of Dixon: the changing image of the TV cop’) established a dialectical relationship between Dixon of Dock Green and The Sweeney, claiming that the conflict between friendly, paternal uniformed police and rule-breaking ‘coppers in disguise’ was embodied in the 1980s series The Bill (Thames/ITV Studios, 1984-2010). For Reiner, the author of ‘The dialectics of Dixon’, The Bill ‘established a state of equilibrium’ through its dramatisation of the tensions between uniformed police officers and the more non-conformist members of the CID; in this way, the series ‘achieved a balance between [the representation of policing as] care and control, and between bobby and detective’ (Reiner, cited in Leishman & Mason, 2001: 101).  One of the most interesting aspects of New Scotland Yard is its dramatisation of the conflict between these two different approaches to policework (or rather, its representation in film and television) through the dialectical relationship between Detective Chief Superintendent Kingdom (John Woodvine) and Detective Sergeant Ward (John Carlisle). The dialogue between the two often underlines the social issues at the heart of each episode, to the point that the episodes sometimes almost become didactic. In ‘Bullet in a Haystack’, for example, Kingdom and Ward pursue a man who is targeting the people who were responsible for the deaths of his wife and children: people whom the law is unable to touch. Ward reminds Kingdom of the irony of this and, to Kingdom’s consternation, suggests that the police delay their arrest of the man, giving him the time to carry out the murders he has planned. One of the most interesting aspects of New Scotland Yard is its dramatisation of the conflict between these two different approaches to policework (or rather, its representation in film and television) through the dialectical relationship between Detective Chief Superintendent Kingdom (John Woodvine) and Detective Sergeant Ward (John Carlisle). The dialogue between the two often underlines the social issues at the heart of each episode, to the point that the episodes sometimes almost become didactic. In ‘Bullet in a Haystack’, for example, Kingdom and Ward pursue a man who is targeting the people who were responsible for the deaths of his wife and children: people whom the law is unable to touch. Ward reminds Kingdom of the irony of this and, to Kingdom’s consternation, suggests that the police delay their arrest of the man, giving him the time to carry out the murders he has planned.

On the whole, the episodes are quite heavily issue-led. ‘Weight of Evidence’ features a particularly vicious bank robbery in which a woman is partially blinded when one of the robbers squirts ammonia into her eyes, after which one of the robbers, a conscience-stricken Eddie (Bob Hoskins), comes forward to ‘shop’ his associates. Eddie has a wife and child, so his decision to offer information to the police isn’t made lightly. However, in court he finds himself in a precarious situation when he finds himself charged with the assault that nearly blinded the bank’s customer, and at the end of the episode Eddie is sentenced for both his part in the robbery and the assault (which he did not commit); the other thieves are given lesser sentences. We are left with the awareness that the flaws within the legal system have left Eddie and his family, who have chosen to ‘do the right thing’, open to retaliation from his accomplices. Both Ward and Kingdom openly express their frustration at this, but they are unable to change the situation – although Kingdom suggests, half-heartedly, that Eddie may be able to appeal against his sentence. (In this episode, Ward also highlights the issue of semantics within the law: ‘Why is it always robbery with violence, with the violence that’s an afterthought?’, Ward asks: ‘We should ensure the balance of charges within the system is appropriate’.)  Likewise, in the first episode of this third series (‘Where’s Harry?’), Kingdom finds himself in conflict with another detective, George Mayer (Anthony Langdon). Kingdom and his team are pursuing an escaped convict, a man whom Mayer put away years previously. Mayer takes the convict’s escape personally: he’s a violent offender who was sentenced to 25 years in prison, ‘and that makes him very dangerous for us and the ordinary citizen’, Kingdom says. However, Kingdom discovers that during the course of the investigation, Mayer has threatened suspects with violence. ‘If you don’t cool it, I’m going to have to do something about it’, Kingdom warns George, eventually pulling him off the case when an interrogation threatens to get out of hand. The maverick Mayer eventually meets a quite brutal end when he confronts the escaped convict by himself. (Incidentally, this sequence, in which Mayer is shot in the gut and, in the aftermath, tries to escape into the street, is as strong as any you could expect to find in British television of the era.) Likewise, in the first episode of this third series (‘Where’s Harry?’), Kingdom finds himself in conflict with another detective, George Mayer (Anthony Langdon). Kingdom and his team are pursuing an escaped convict, a man whom Mayer put away years previously. Mayer takes the convict’s escape personally: he’s a violent offender who was sentenced to 25 years in prison, ‘and that makes him very dangerous for us and the ordinary citizen’, Kingdom says. However, Kingdom discovers that during the course of the investigation, Mayer has threatened suspects with violence. ‘If you don’t cool it, I’m going to have to do something about it’, Kingdom warns George, eventually pulling him off the case when an interrogation threatens to get out of hand. The maverick Mayer eventually meets a quite brutal end when he confronts the escaped convict by himself. (Incidentally, this sequence, in which Mayer is shot in the gut and, in the aftermath, tries to escape into the street, is as strong as any you could expect to find in British television of the era.)

Other episodes confront the issues of the era in similarly direct terms: in a plot that foregrounds the conflicts within a Europe that, at the time, was dealing with the actions of the Brigate Rosse and the Rote Armee Fraktion, ‘Crossfire’ finds Kingdom and Ward enlisted to help find the son of the ambassador for a Central American country. The young man has been kidnapped by left-wing radicals. Kingdom notes that ‘there are certain journalists that are all too ready to produce fiction’ but reminds the ambassador that ‘We’re not accustomed to muzzling our press’. When the ambassador suggests that they should simply pay the ransom, Kingdom warns the family, ‘You give into these people once, you open the floodgates [….] No politician, no industrialist, no diplomat will be safe’. Similarly, ‘Property, Dogs and Women’ confronts the hot potato topic of youth violence. Kingdom and Ward are called in to help investigate a district that has featured a stark increase in crimes committed by youths, with a particular escalation of violent offenses. When Ward, walking through the area, encounters some youngsters playing football amongst half-demolished houses (an obvious signifier of the poverty of the area), he strikes up a rapport with them (the youths are unaware that Kingdom is a detective). ‘If you wanna make yourself useful, keep your goggles open for the flies [….] the bluebottles. We’re not supposed to play here’, one of the kids says. Kingdom soon realises that a strong resentment has built up between the youths and the police, partly due to the strong-arm tactics that the local coppers have been employing: the boy tells Kingdom that ‘that’s what coppers are for, to look after rich people’.  The last five episodes are slightly less impressive: they trade public spaces for domestic settings (a monopoly game in a middle-class home after which one of the participants is murdered; a woman strangled to death in her home, apparently by a gigolo; the owner of a gym is murdered, seemingly over an affair his wife was conducting with one of his associates; a wealthy man returns home to find a dead body in his luxurious flat). These later episodes also attempt to ‘humanise’ Kingdom by offering glimpses of his home life: in one of his episodes, we see his clumsy, disconnected relationship with his wife, for example. The last five episodes are slightly less impressive: they trade public spaces for domestic settings (a monopoly game in a middle-class home after which one of the participants is murdered; a woman strangled to death in her home, apparently by a gigolo; the owner of a gym is murdered, seemingly over an affair his wife was conducting with one of his associates; a wealthy man returns home to find a dead body in his luxurious flat). These later episodes also attempt to ‘humanise’ Kingdom by offering glimpses of his home life: in one of his episodes, we see his clumsy, disconnected relationship with his wife, for example.

DISC ONE: ‘Where’s Harry?’ (52:23) ‘Diamonds are Never Forever’ (51:39) ‘Bullet in a Haystack’ (50:12) Gallery DISC TWO: ‘Weight of Evidence’ (51:44) ‘Crossfire’ (51:26) ‘Property, Dogs & Women’ (50:56) DISC THREE: ‘Exchange is No Robbery’ (51:35) ‘Daisy Chain’ (52:50) ‘Don’t Go Out Alone’ (52:12) DISC FOUR: ‘The Stone’ (51:57) ‘Monopoly’ (52:32) ‘Rogue’s Gallery’ (52:38) ‘Pier’ (51:50)

Video

New Scotland Yard was shot on a mixture of videotaped studio footage and 16mm location work. The discrepancy between these two formats is clear from within the episodes themselves (the videotaped footage shos the hallmarks of that format: a lack of dynamic range, burnt highlights, weak contrast). Nevertheless, the presentation of these episodes on this set is strong, with very little damage evident throughout.

All of the episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 1.33:1.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel mono track. This is clear, although there is an audible low hum on episode one. This is not too problematic, however, and doesn’t drown out the dialogue or overshadow other aspects of the sound design. Sadly, there are no subtitles.

Extras

The sole ‘extra’ is a stills gallery on disc one. This is a shame, as very little has been written about this series, and it would have been nice to see some sort of contextual material.

Overall

New Scotland Yard is an entertaining series that, as with many police dramas, is largely issue-led. Woodvine and Carlisle work well together on the screen, and the relationship between Kingdom and Ward (and their conflicting views on the cases they are presented with) is one of the highlights of this series. This third series of New Scotland Yard features some strong episodes. The final handful of episodes tail off slightly and become more conventional in their deployment of a ‘whodunnit’ formula and their shift from public issues (youth crime, terrorism, etc) to domestic settings. Nevertheless, there is still much to enjoy in these episodes. Those who have bought and enjoyed Networks’ releases of the previous two series of New Scotland Yard will find much to enjoy here. References: Delaney, Sean, 2003: ‘TV Police Drama’. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/445716/index.html Leishman, Frank & Mason, Paul, 2001: Policing and the Media: Facts, Fictions and Factions. London: Willan Publishing This review has been kindly sponsored by:  . .

Please visit Network’s website here

|

|||||

|