|

|

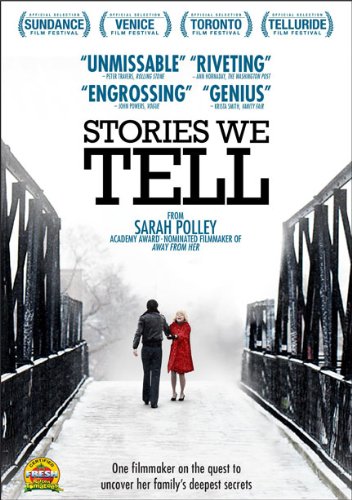

Stories We Tell

R1 - America - Lions Gate Home Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Ethan Stevenson (10th February 2014). |

|

The Film

"When you're in the middle of a story, it isn't a story at all but rather a confusion, a dark roaring, a blindness, a wreckage of shattered glass and splintered wood, like a house in a whirlwind or else a boat crushed by the icebergs or swept over the rapids, and all aboard are powerless to stop it. It's only afterwards that it becomes anything like a story at all, when you're telling it to yourself or someone else." There are stories; there are truths. Some elaborate stories are not true; some truths are not elaborate stories. For years, when I was very young, I was told supposedly true stories by my aunts, on my father's side of the family, who insisted that my paternal grandmother, a James by birth and born in Missouri, was a descendant of famous 19th century outlaw Jesse (you know, the one assassinated by the "coward" Robert Ford). My father never really bought into it; he'd been told the same tale many times in his youth, by his sisters and his mother, and grew skeptical with each passing telling, because the details changed from time to time. Whenever his sisters would bring the Jesse James connection up, he was eager to remind my brother and I that it was just a rumor. It "probably" wasn't true, he'd caution. Years later, in the latter part of the 1990's, with the democratization of information thanks to the wonders of the Internet--that once-and-for-all ender of argument and debate--an investigation of genealogy proved the James tale to be tall indeed. I am not, nor is any part of family, related to Jesse James. Ask my aunts about it today, and most of them try to backtrack, and claim they never so adamantly insisted such a thing; they merely mentioned it a possibility, not fact. (Although, funnily enough one still says that we are related to him, and the Internet is wrong!) A relatively unbelievable story that'd somehow lived on through two generations, it's become kind of a joke in my immediate family now. It would have hardly been harmful had it been true in the first place, and it's still a fun anecdote either way, even now that it's turned out a complete fabrication. Now, on the flip-side of the same coin, a far more hurtful roundup of unsubstantiated rumors found their way into a manuscript a cousin on my mother's side had passed around in a group email to the family a few years ago. This cousin took it upon themselves, as one of the oldest living relatives, to tell the story of that side, dating all the way back to my immigrant great-great-grandparents’ arrival in America. In their writing, the cousin elaborated on a number of scandalous stories passed on from aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters, parents, grandparents and so on; many of the accounts were half-truths, unconfirmed claims, or outright lies carefully sprinkled between verified records of things both insignificant and equally almost too outrageous but nevertheless were true. My maternal grandmother was so upset, and deeply hurt, by what the cousin had written--no matter how much of it was at least even partly accurate--that she cut off contact with them for a considerable amount of time. Even now, with bridges mended, she refutes most of the would-be memoir with a simple, "well, that's not how I remember it!" My point is, memory is fickle, and the fabric of family is a thread easily cut by the scissors of scandal. The story of "our" past often takes on a life of its own, and sometimes the "truth" is pretty far from factual reality. Rather, the objective narrative becomes informed by the subjective--the experiences and bias of each person passing it on. The story takes shape, and evolves, until it's almost like a living, breaking thing, shifting and changing until, like a bad game of telephone, the input and output are entirely different; the main message horribly muddled and morphed along the way. In part, that's exactly what Academy Award nominated writer/director and actress Sarah Polley set out to explore in her first documentary, "Stories We Tell". "Every family has a story", says Sarah's sister Joanna Polley at the start of the film. Indeed, on some level that is a universal truth; one of the few things I think everyone in this documentary of conflicting comments and contractions, would agree on. For Sarah, her story starts with Michael Polley, a man who, for years, she thought was her father, and Diane Polley, her mother, who died when Sarah was 11 years old. Michael was a writer and respected actor in the 60's Toronto theatre scene; Diane was an actress of the same. They met during a production, and, by most accounts, instantly fell in love. Michael--a kind but emotionally complex and intermittently distant (and sort of odd) individual--was the complete opposite of Diane, who's portrayed as a free spirit and the "life of the party". Michael was the wallflower; the man who was perfectly content listing to music by himself in a quiet room adorned with books and comfy chairs. Diane was the girl with flowers in her hair, and would rather listen to the song on the dance floor of a club. Still, they settled down, had a few kids together, and for the most part lived happily ever after… until the problems started, Diane had an affair, and gave birth to baby Sarah. At least, that's one person's version of the story; others tell it differently. A lot of “Stories We Tell” is about the differences within the same story; how a person’s point-of-view and own backstory informed their perception of what was going on at the time. At one point in the film, when the interviewees are talking about Diane's pregnancy with the youngest Polley girl, Sarah’s half-brother John Buchan says his mother was "overjoyed" by the newness of another baby; a good friend of Diane on the other hand recalls that the mother-to-be was not pleased she was pregnant "at all." She repeats "at all" in a couple of forms to Sarah's camera, to the point where you sort of feel sorry for the director. Sorrier still when we learn that the baby was so unwanted, Diane had decided to terminate the pregnancy that would eventually birth a baby Sarah, not wanting to expel a child she wasn't even sure was her husband’s offspring. Obviously, as Sarah is here to make this film, Diane changed her mind… why is anyone’s guess. It’s one of the elements of this story that no one cares to question or give their own answer to. The untenable reasoning and questionable circumstances that lead to Diane's affair and Sarah's birth are not glossed over. In fact, they're exposed in embarrassing, exacting, and excruciatingly personal detail. But the film is never mean, and Diane is rarely condemned for her actions or demonized. To her credit, Sarah keeps her opinion of Diane, whom she was never close to (only in part because her mother died young), close to her chest until the final moments of the film, and even then I see it as less a scathing attack on her deceased mother and more an additional comment on the peculiarities of the way we tell stories, and the meaninglessness of holding out for an objective truth. Instead, Sarah seems concerned with fleshing out her mother as a person, and turns to her friends, family members and others to give a clear picture of who Diane Polley was, and importantly why she was the way she was. "Stories We Tell" is only partly about Diane, just peripherally about Sarah’s childhood, and only ostensibly about the quest for objective truth. It's also about Sarah Polley's journey to discover the identity of her biological father, and her investigation--which leads to three possible suspects; two actors, and a Canadian movie producer--is a fairly compelling mystery, unwinding with several interesting twists and turns. The film’s a complex character drama; although these all real people, the way Sarah constructs her story, and the amount of time she spends trying to contextualize the environment she was born into, makes the film feel less like a documentary and more like one of her lived-in fiction features ("Away From Her" (2006) and "Take This Waltz" (2011)). In broader terms, "Stories" is simply a film about family and what the word even means now. The film is about the making and breaking of unit, the bond of those who share the same genes, and those few who have no real reason to be together at all yet still are. One of the sweetest parts of the film and the Polley family story as a whole, is the relationship Sarah and Michael have to this day. Michael raised Sarah as his own, for the most part on his own, because until recently he thought she was, and Diane wasn't around to do or say about otherwise. In the end, the revelation that they're biological strangers has no negative impact; in fact, it drives them closer together than ever. Sarah says Michael will always be her dad because he always has been (awwww). A documentary like this runs into dangerous problems of pretension if done the wrong way; even Sarah's family show skepticism and apprehension in opening and airing out their dusty closet of family secrets, because it's so personal no one but them might get any meaning from it. One of Sarah's sisters admits that part of her wonders "who the f*** cares about our family?" But credit to Sarah Polley, who has a sure hand of the production throughout; she makes it very easy to connect with these people, and presents their story in such a way it's almost immediately interesting—something you want to see to the end. Although it takes a little while to find it’s footing, the film falls into an interesting rhythm, and she approaches the subject with a rather novel twist on the traditional documentary. She breaks the form, playing into the artifice and fakery of film, blurring the line between what's real and what isn't. She shot a majority of “Stories”, including some of the interviews, on Super 8mm, and blended real home movies of her mother, Michael, and siblings with elaborate recreations using actors. The unique approach just enhances and enriches the strong "characterization", and moves the film away from the stale talking head format so prevalent in the genre; the final act integration of the fakery into the film, as Sarah turns the camera toward herself and why she wanted to make this piece, adds another intriguing layer. "Stories We Tell" is one of the more interesting films, documentary or otherwise, I've seen in a while. It's a compelling mystery, a fascinating character piece, and a brilliant deconstruction of the documentary form. It’s a rare film that actually gets exponentially better (and certainly more introspective) as it rolls along, building upon bits and pieces of its story to create and even more elaborate narrative marked by many unexpected turns. Sarah Polley walks a very fine line through the whole thing, but never steps over to the wrong side of too long, always course correcting whenever she wanders astray. There are aspects unexplored, and questions left unanswered, and on some level, that does make "Stories" feel incomplete. But I suppose that's life; some things are unknowable and out of our control. Some stories have a beginning and middle, but, as Sarah and her family are still living their lives, the end hasn't been written yet.

Video

Sarah Polley and cinematographer Iris Ng shot "Stories We Tell" on two radically different formats. Present day interview footage was captured with Sony CineAlta cameras, and the the HD-native footage is crisp and clean, with natural colors and stable contrast. Interspersed with the modern digi-cam material are a few archival bits of varying quality, from black-and-white Kinescopes of Sarah's mother to an excerpt of "Marriage Italian Style" (1964), and more, including copious amounts of Super 8 home movie footage, both real and nostalgic recreations, filmed with vintage Nikon and Canon cameras on Kodak Ektachrome stock. The end result is a unique look, replete with jarring inconsistency. Clear and sharp images give way to thick grain, pallid skin tones and ruddy colors, with all the inherent quirkiness of old Super 8 cameras and stock--flashing, slightly jerky under-cranking, out of focus handheld camera moves, and some faint damage in the form of nicks and dirt (some artificial, some not). Lionsgate's DVD is at the mercy of the source; presented in 1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen, some of the time it looks good, with decent detail in the newer material, but has an expectedly rough time with the chunky Super 8 format, reducing much of the grain to blocky noise. On the plus side, the transfer appears untouched by edge enhancement or other types of processing. It's really a shame this was a DVD only release; I understand the hesitance to bring a film to Blu-ray when so much of it is for a lower gauge film-stock, but there's really no excuse in this day and age. The film was finished on a 2K DI, and an HD master exists. A Blu-ray should've been offered (and one is available in other regions, through a different distributor). The superior compression codecs of the HD format alone would render the texture and grain of the 8mm footage better, and further add to the interesting contrast of styles. As is, the DVD hardly does justice, although very little of that has to do with the authoring or mastering of the disc, and is more an issue with the general inferiority of the format.

Audio

"Stories'" soundtrack is much more straightforward than the complicated, intentionally schizophrenic visual style. The English Dolby Digital 5.1 track is fairly plain, with very little natural atmosphere (police sirens wail in the distance in one scene, but that's about it), and there's no bass to speak of. Unsurprisingly, the film is talky, and front focused; a majority of the Super 8 footage is "silent", with narration from Michael Polley laid on top with music. Surrounds are limited to a slight opening up of the score, almost entirely comprised of piano tunes pulled from an album released in the 1970's called "Play Me A Movie", a compilation of material by silent film accompanist Abraham Lass. A frequent collaborator, and The Most Interesting Man in the World, composer/commercial spokesperson Jonathan Goldsmith acted as music supervisor on the film. English and Spanish subtitles have also been included.

Extras

The only extra is a theatrical trailer (1.78:1 anamorphic widescreen; 2 minutes 18 seconds).

Overall

"Stories We Tell" is a fascinating documentary, both in form and subject. It's as much a film about the making of a family as the breaking of one, and vice versa. It's about the secrets, lies, and half truths whispered or unspoken between bonded and betrothed, and how these same sordid stories seem to have a life of their own, details changing over time, entirely dependent on who's telling them. "Stories" is also an enthralling detective film, with a compelling mystery; and it has rich, complex "characters". The film transcends the non-fiction documentary form, and blurs lines between genres--ultimately becoming sort of its own biased fictional take on factual reality. Sadly, the DVD release is a very mediocre offering, with no meaningful extras and a A/V transfer at the mercy of an intentionally degraded source. In the end, it's the strength of the film makes this one worth a look.

|

|||||

|