|

|

The Film

Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal / The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal (Walerian Borowczyk, 1967)  This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release. This disc is available both as part of Arrow’s Camera Obscura: The Walerian Borowczyk Collection, and individually as a standalone release.

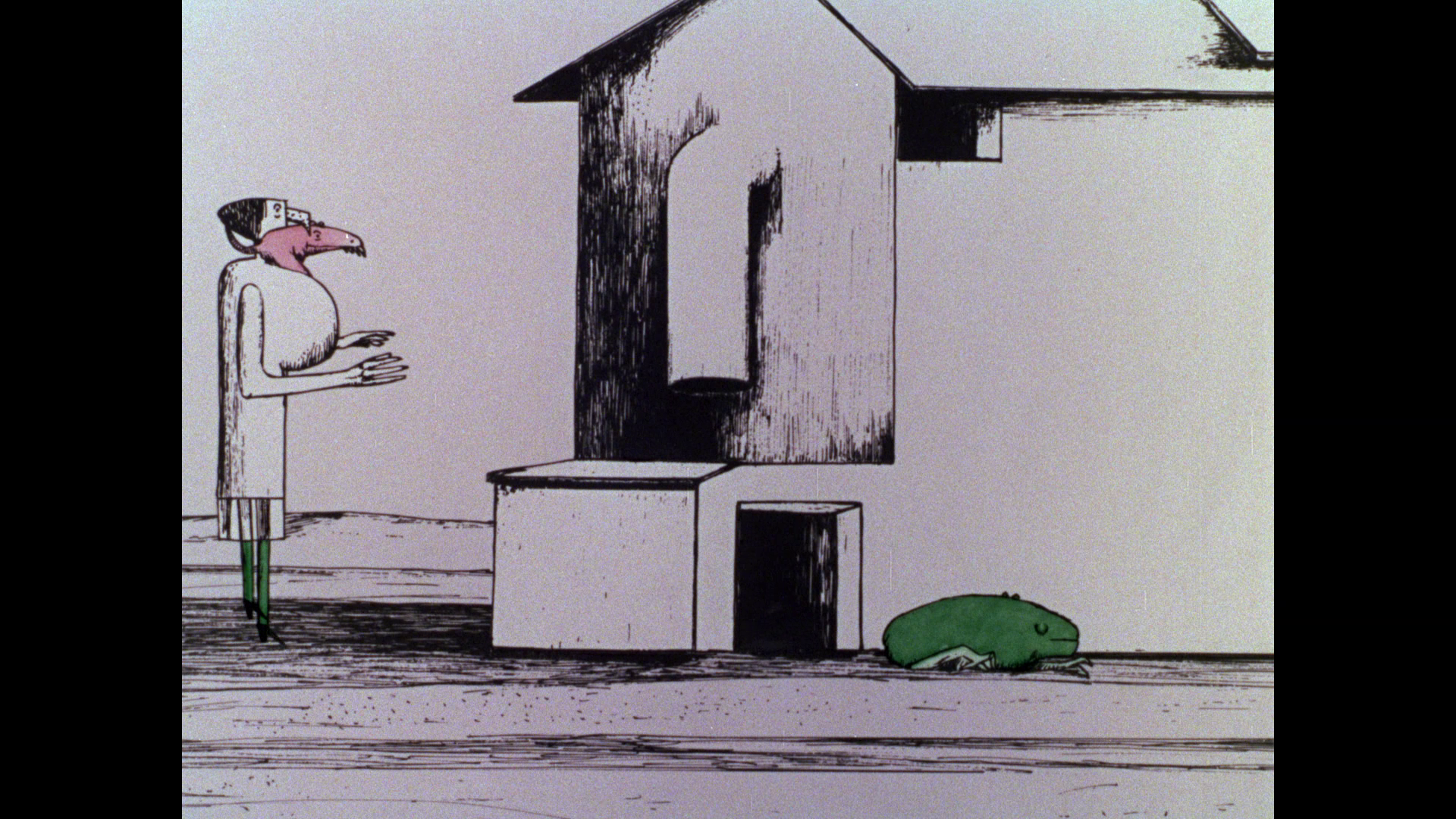

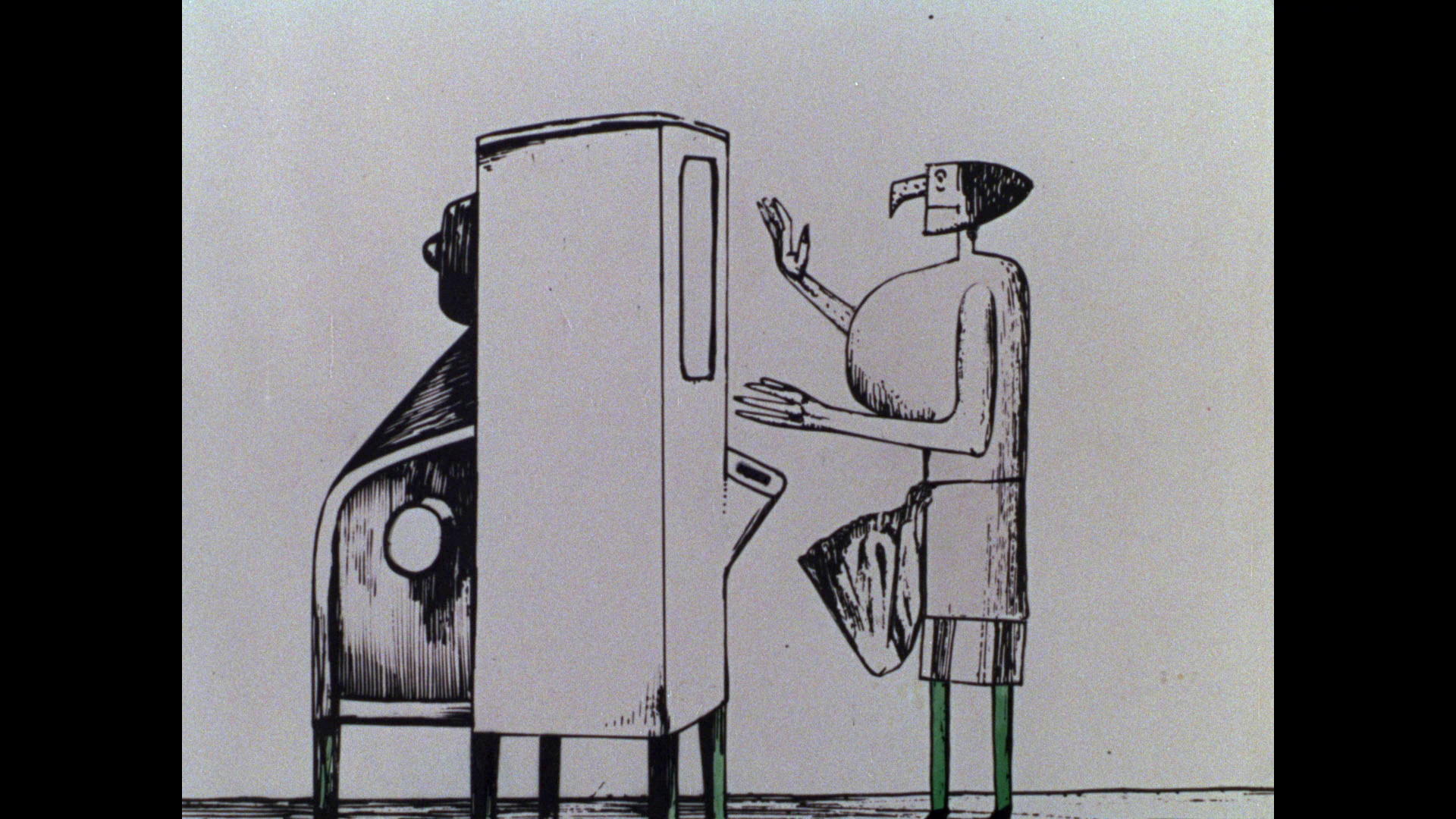

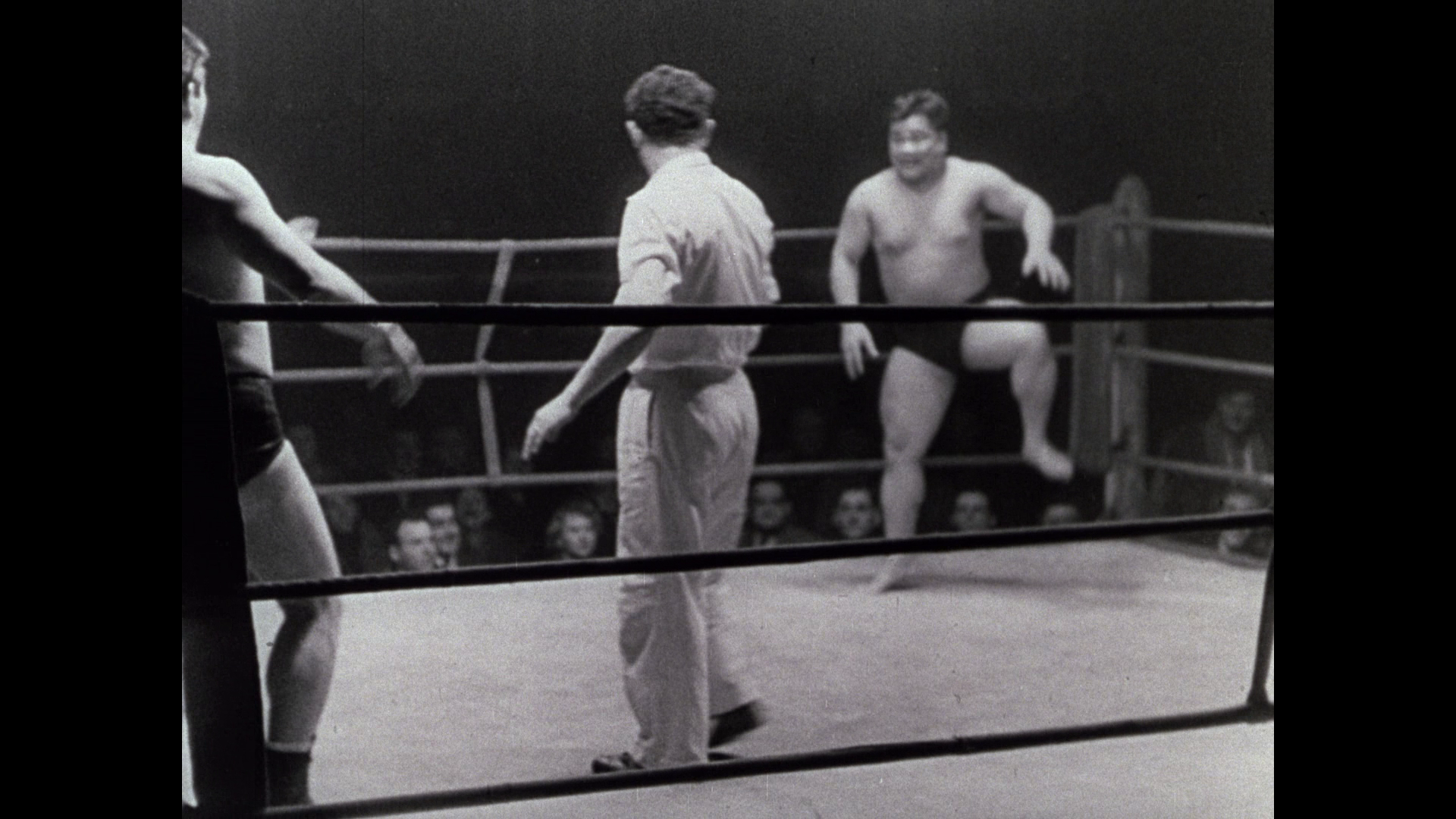

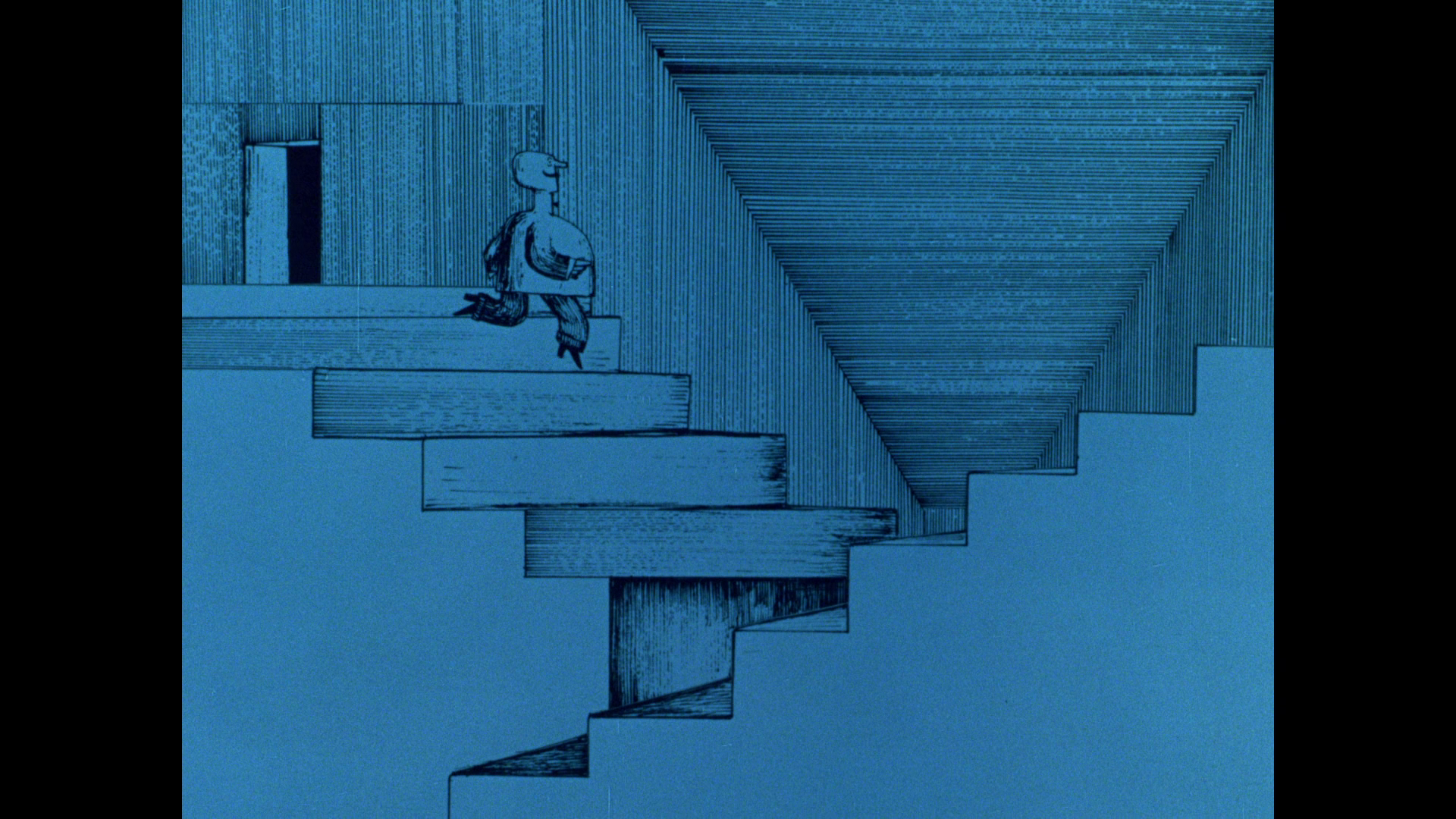

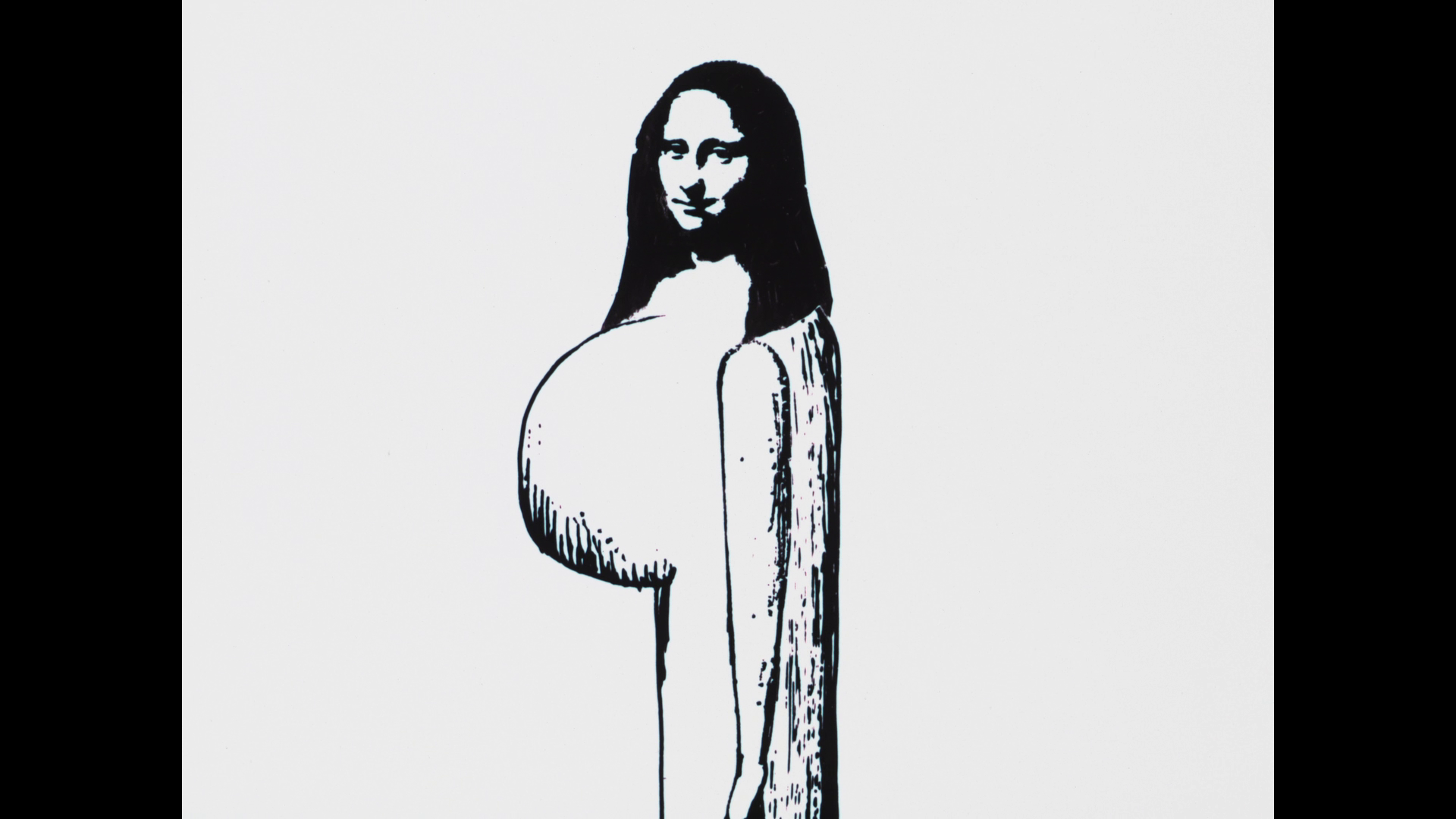

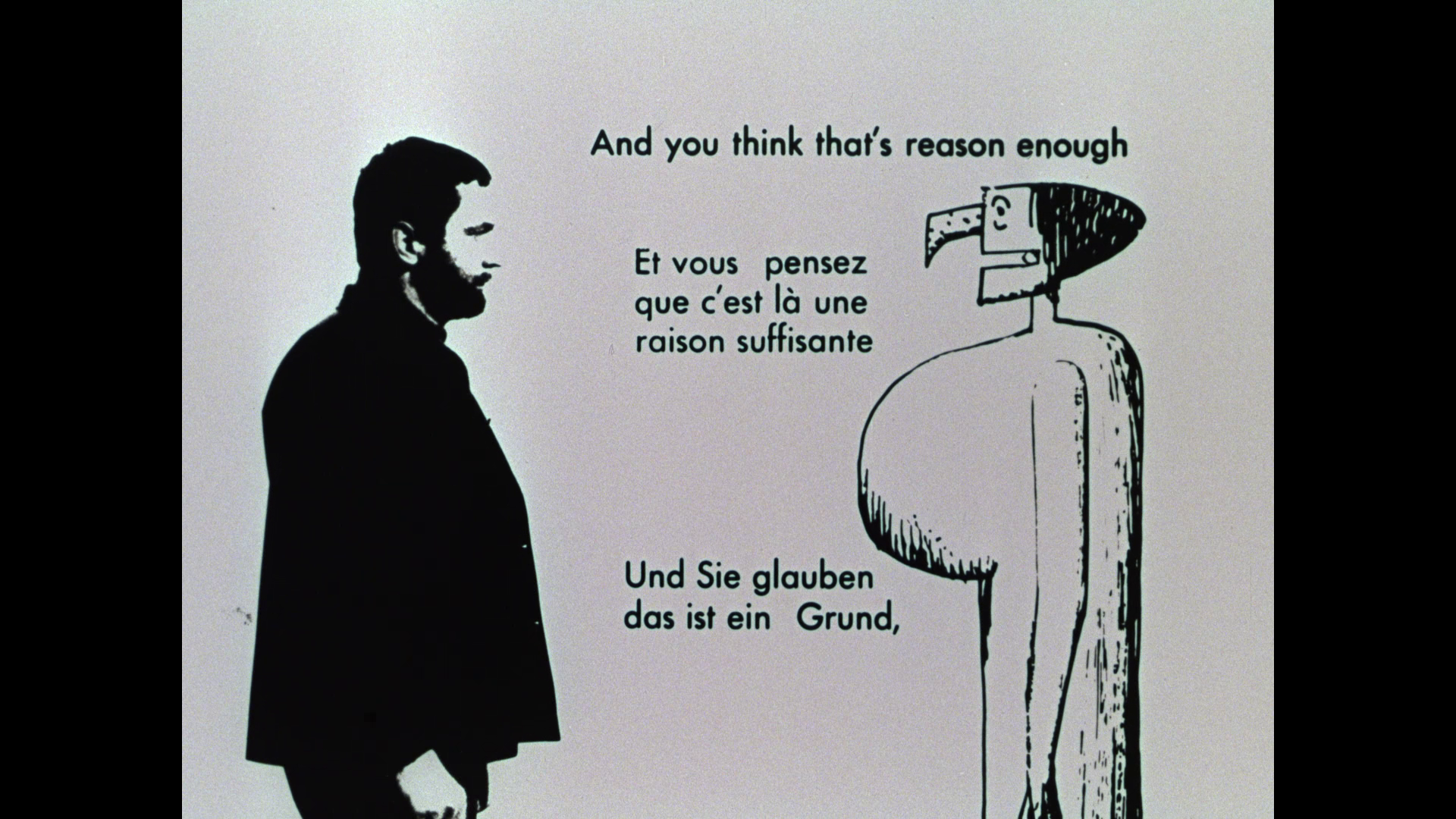

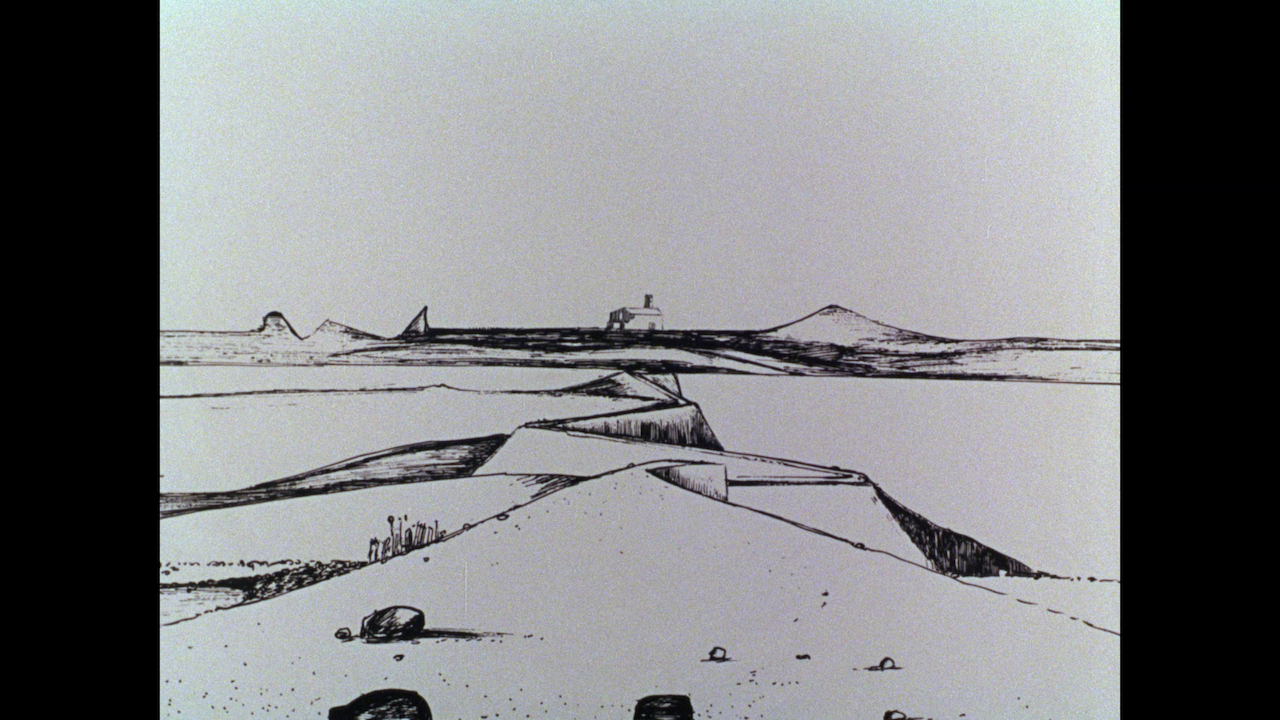

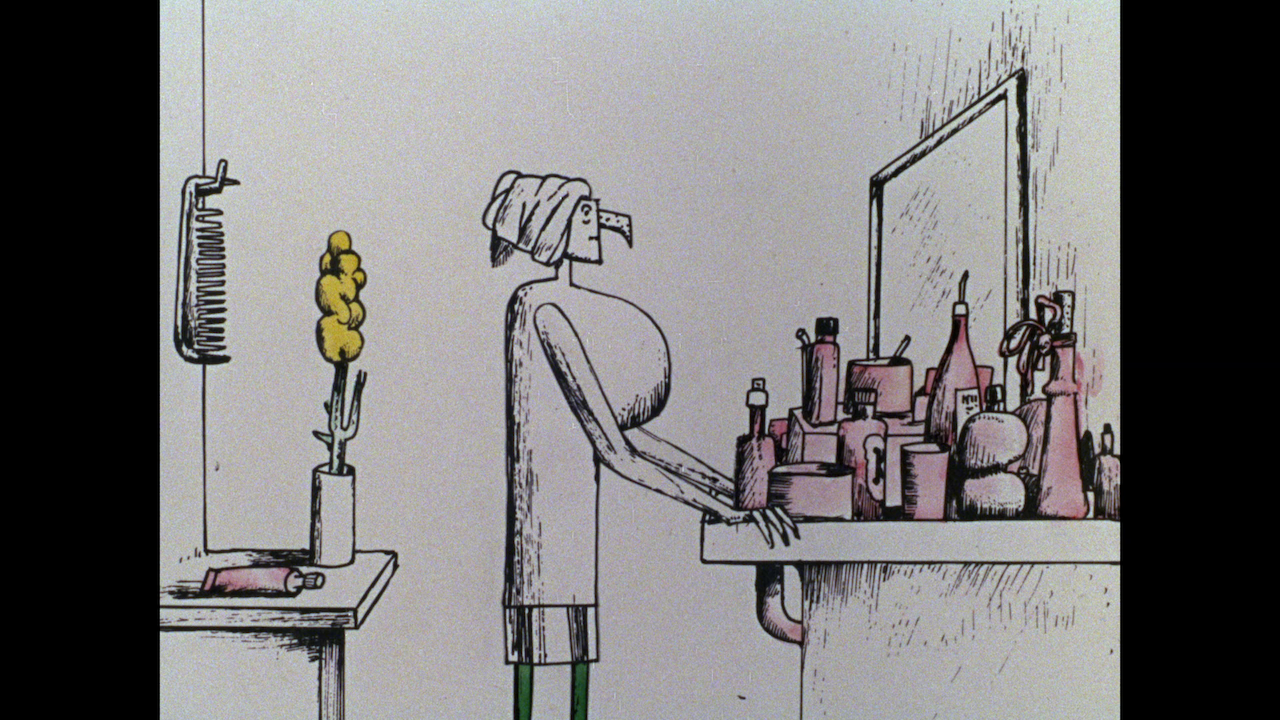

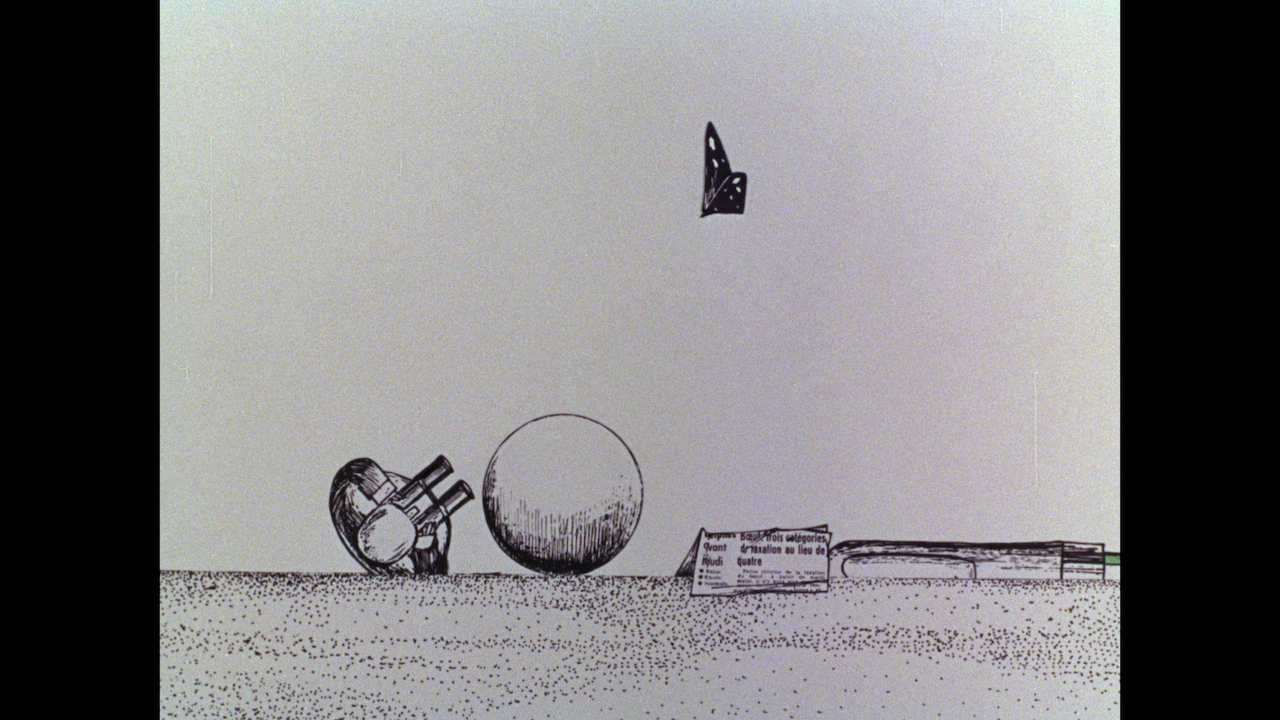

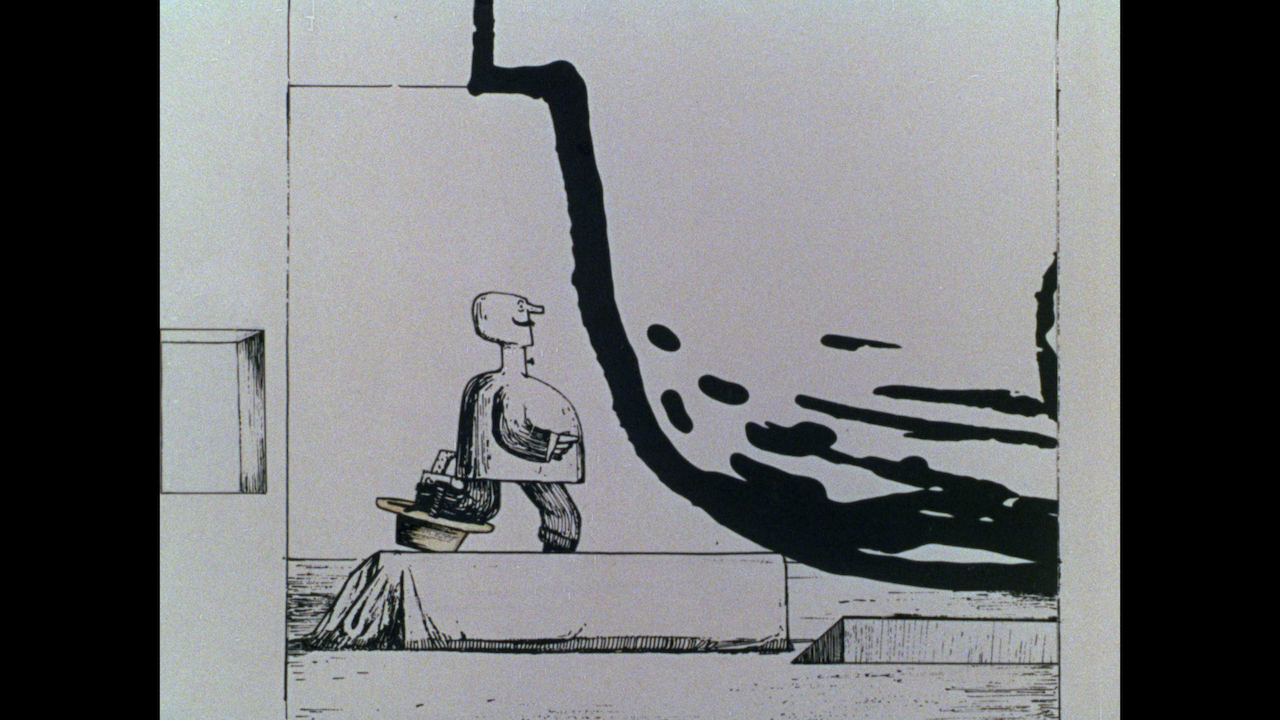

NB. Links to reviews of the other Borowczyk discs will be added to this review as they go ‘live’ over the coming week. - Our review of Blanche (1971) can be found here. - Our review of The Beast (1975) can be found here. - Our review of Goto, Isle of Love (1968) can be found here. - Our review of Immoral Tales (1974) can be found here. In a press conference transcript published in Positif, Borowczyk’s first feature film Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal (The Theatre of Mr and Mrs Kabal, 1967) was mentioned by Chuck Jones in juxtaposition with his own Road Runner cartoons, which one member of the audience (described in the transcript as ‘The Old Lady’) suggested were too heavily reliant on violence. Jones noted that his films were intended to make people laugh, and the violence within them is cathartic. By contrast, Jones notes, he ‘took notes on the films shown at the Annecy, and I noticed that at least a third of them reflected a veritable obsession with death. There are decapitations, dismemberments’ and a ‘morbidity that is typically European […] Americans are possibly preoccupied with violence, but in Europe, it’s death and decomposition which seems to rule the imagination’ (Jones, quoted in Thompson, 1976: 127). One of the European films that Jones cites in the interview as displaying this fascination with ‘death and decomposition’ and features decapitations and dismemberments is Borowczyk’s Théâtre de Monsieur & Madame Kabal (ibid.). Having studied painting at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts, Borowczyk progressed to a career in graphics, designing film posters (an online gallery of Borowczyk’s film poster designs can be found here). Borowczyk also began to create animated shorts, a number of which were made in collaboration with Borowczyk’s fellow poster designer/illustrator Jan Lenica. One of Borowczyk and Lenica’s first collaborative efforts, ‘Był sobie raz’ (‘Once Upon a Time’, 1957) won a number of awards. However, the highlight of Borowczyk and Lenica’s Polish shorts is probably ‘Dom’ (‘Home’, 1958), winner of the Grand Prize at the 1958 Brussels Experimental Film Festival and nominated for Best Animated Film in the 1959 BAFTAs, which features a dazzling array of animation techniques and the juxtaposition of animation with live action footage. Borowczyk’s collaboration with Lenica ended with Borowczyk’s departure for France in 1959, where Borowczyk collaborated with Chris Marker on ‘Les astronauts’ (‘The Astronauts’, 1959), a satirical examination of the space race. (This disc gathers Borowczyk’s shorts, beginning with ‘Les astronauts’ from 1959, and thus excluding the earlier shorts Borowczyk made in Poland.) Borowczyk had experienced life under both fascism and communism, and the theme of repression (personal, political and sexual) runs throughout both his short films and the features he began making with Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal in 1967. The 1964 short ‘Les jeux des anges’ (‘Angel’s Games’), for example, offers an allegorical depiction of the concentration camps that begins with the ominous sound of a train. Michael Richardson has suggested that Borowczyk’s shorts show the first evidence ‘of his tragic vision’, which would come to dominate his feature films, ‘in which all things are overwhelmed by entropy’ (2006: 109). Borowczyk’s worldview, Richardson argues, is dominated by a perception of the ‘instability of things and the fundamental perversity of the human will to impose order on nature [which] combine to create tragedies that cannot be contained’ – a view of the world that, for Richardson, was rooted in Borowczyk’s experience of totalitarianism (ibid.). Richardson suggests that Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal has its roots in symbolist writer Alfred Jarry’s characters of Ma and Pa Ubu, who first appeared in Jarry’s 1896 absurdist play Ubu Roi. Jarry’s work is ‘meta’ in a way that anticipates much of the modern and postmodern art of the 20th Century, mixing genres and exhibiting a playful approach to form and theme; and the plays (especially Ubu Roi) have been seen as forerunners of both the Theatre of the Absurd and, more generally, surrealism. Certainly the Kabals have some similarities with Ma and Pa Ubu (animalistic, and simultaneously foolish and menacing, their relationship driven by conflict), and the absurdist world in which they find themselves – and their equally absurdist response to it – is darkly funny. Mrs Kabal is, or appears to be, a huge robot; Mr Kabal, by contrast, is diminutive and passive. They live in an oddly-shaped house surrounded by four-legged, sharp-toothed creatures and butterflies. When Mrs Kabal swallows some of these butterflies, Mr Kabal visits the cinema and watches a medical film (‘The Depths of Body’) before attempting amateur surgery on his wife at home, sawing her head off and injecting her with a serum that makes her body grow. When her body reaches an appropriate size, Mr Kabal climbs into her and, exploring her cavernous interior, helps to alleviate her problem by catching the butterflies that are plaguing her insides. Recovered, Mrs Kabal watches violent clips on a Kinetoscope-like device that the Kabals have in their home (including repeated monochrome footage of wrestlers in action and, later, aerial shots of mushroom clouds apparently caused by nuclear explosions). Inspired by these, Mrs Kabal turns the Kabal home into an impromptu munitions factory. The animation predominantly features black ink on white backgrounds (though when Mr Kabal ventures into the interior of Mrs Kabal, this changes to a blue background, perhaps denotative of the darkness inside her). Flashes of colour appear now and then: the green of the Kabal’s pet, contrasted with the red of the wild animals (presumably of the same genus) that live around the Kabal’s house, and which occasionally attack the Kabals and their pet; the colourful butterflies; the green of Mrs Kabal after she has ingested the butterflies, symbolising the fact that she is ill. After Mrs Kabal has watched the same monochrome wrestling clip repeatedly (a sequence that, beginning with the rhythmic stomping of a wrestler’s feet, is rendered absurd through the repetition of the same events), she grows muscular arms and legs which are given a pinkish hue, before giving chase to Mr Kabal. (Later, after watching nuclear explosions on the same Kinetoscope-type device, she decides to turn the Kabal house into a functioning munitions factory – which seems to be Borowczyk’s subtle comment on ‘media effects’ debates and the suggestion that films, etc, cause ‘copycat’ behaviour.)    Kabal is a difficult film to discuss, given its absurdist nature, but it has a narrative of sorts (as outlined above). Borowczyk mixes animation with live action footage, to remind us that both forms essentially operate like a flickerbook. Repeatedly, Mr Kabal pops out of a hole with his binoculars in hand, the lenses extending telescopically, and Borowczyk cuts to Kabal’s perspective: an attractive young woman (a different woman each time), usually in a bikini, who is either sunbathing, rowing a boat, eating a banana or hitchhiking. Kabal’s moment of scopophilic pleasure is undercut when the woman returns his gaze and/or an elderly, bearded man enters the scene (from behind an object, or entering from the side of the film frame) and acknowledges Kabal’s voyeurism, shaking a fist at him or glaring threateningly towards the camera. In each case, accompanied by an abrupt noise on the soundtrack, Kabal’s binoculars ‘collapse’ and Kabal retreats back to the hole from which he came. This motif, repeated throughout the film, could perhaps be described as a voyeur’s L’Age d’or: Kabal’s voyeuristic pleasure is repeatedly frustrated.    Another notable instance of live action footage takes place when Kabal, apparently investigating ways of curing his wife (who has swallowed a butterfly, rather like the old woman who swallowed a fly), visits a cinema and watches a medical short, ‘The Depths of the Body’. The clip features narration over footage of a heart beating, and repeated shots of an endoscope exploring the interior of the human body, beginning by bypassing the tonsils and entering the patient’s throat. Over this, the narrator tells us, ‘The heart, this fist-sized organ, is our body’s engine. But man, in search of his secret, couldn’t content himself with this game. As soon as he stepped through the threshold of the vocal cords, he dove deep into the living body, into lungs, through mineshaft-like corridors, until he reached the place of death’. Mr Kabal, who remains silent throughout the film (and thus hasn’t crossed ‘the threshold of the vocal cords’), returns home and performs impromptu surgery on his wife; Borowczyk then visualises the interior of Mrs Kabal’s body as a series of ‘mineshaft-like corridors’, offering a literal interpretation of the metaphors used by the narrator of ‘The Depths of the Body’ and thus offering an ironic counterpoint to the medical short Borowczyk watches in the cinema (and which interrupts the narrative of the film).   Borowczyk himself even appears within the film, via the magic of rotoscoping, in the opening and closing sequences – introducing and concluding the film. In the opening sequence, Mendelssohn’s Wedding March is heard as Mrs Kabal’s body is drawn on the blank page/screen. (We hear the scratching of a pencil as the image appears on the screen.) Then the head is drawn. The arms of Mrs Kabal reach up and screw the head up, discarding it – clearly unhappy with it. This happens repeatedly (at one point, Mrs Kabal hesitates before similarly discarding the face of the Mona Lisa, which has been drawn above her body). Finally, she settles on a bullet-shaped head with a beak-like nose. Borowczyk appears on screen, and Mrs Kabal speaks with a grating metallic voice. As she speaks, subtitles in several languages (including English) appear, drawn on the screen. ‘Who are you?’, she asks. Borowczyk introduces himself as ‘Boro’, noting, ‘I just drew you, madame’. ‘And you think that’s reason enough to enter a lady’s room without knocking?’, she asks. Boro asserts that he has come ‘to go over today’s programme with you […] We need you to fill the next 80 minutes with your acting’. Mrs Kabal protests that she is not an actress. ‘Just be yourself’, Boro suggests. With this suggestion, Boro unleashes 75 minutes of absurdity.   The film is uncut and runs for 77:05 mins.

Video

The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and the film takes up approximately 15Gb on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. The presentation exhibits some wear and tear here and there, but is very satisfying, with a level of detail that is consistent throughout. The live action sequences have a good depth and clarity to them too, and the whole presentation looks about as organic and film-like as an animated film from this vintage may be expected to look on a Blu-ray disc. NB. Some larger screengrabs can be found at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The film is presented with a LPCM mono track, in French – though most of the film is without dialogue. This lossless track has good range, evidenced in the snippets of classical music heard throughout the picture (notably Mendelssohn’s Wedding March), and Mrs Kabal’s grating robotic voice. Optional English subtitles are included for the portions of French dialogue.

Extras

Introduction by Terry Gilliam (1:04). This is the same video featuring Gilliam that was used to promote the Kickstarter campaign to restore Borowczyk’s Goto. Gilliam describes Borowczyk’s early flms as ‘dangerous, angry kind of animation’ and highlights the subtly sexual themes of these shorts. 'Film is Not a Sausage: Borowczyk and the Short Film' featurette (28:21). Bookended with an archive interview in which Borowczyk talks about his short films and the approach he took to them (‘I have a psychological need to do it’, he admits), the bulk of this featurette features modern interviews with André Heinrich and Dominique Duvergé-Ségrétin, intercut with footage from the short films under discussion. They talk about the institutional context in which Borowczyk worked whilst making many of these shorts and reflect on Borowczyk’s need to make the props in his films with his own hands. Borowczyk’s collaborations with Lenica are discussed, as are Borowczyk’s commercials, which are presented on this disc. The featurette also includes a vintage audio-only interview with composer Bernard Parmegiani that focuses on the music used in Borowcyk’s shorts. This is presented over images from Les jeux des anges. 'Blow Ups: Borowczyk's Works on Paper' (4:43). This featurette focuses on Borowczyk’s work in print. Short films (1959-1984) (with 'Play All' option; 112:28): - 'The Astronauts' (1959) (12:37) - 'The Concert' (1962) (7:01) - 'Grandma's Encyclopaedia' (1963) (6:51) - 'Renaissance' (1963) (9:18) - 'Angels' Games' (1964) (12:01) - 'Joachim's Dictionary' (1965) (9:26) - 'Rosalie' (1966) (15:07) - 'Gavotte' (1967) (10:41) - 'Diptych' (1967) (8:41) - 'The Phonograph' (1969) (5:41) - 'The Greatest Love of All Time' (1978) (9:38) - 'Scherzo Infernal' (1984) (5:14) Borowczyk’s short films, made between 1959 and 1984, are presented here with a ‘Play All’ (or rather, as it’s labelled on the disc, a ‘Programme’) option. This option presents the films in a non-chronological sequence. Commercials: - ‘Holy Smoke’ (1963) (9:54) - ‘The Museum’ (1964) (1:50) - ‘Tom Thumb’ (1964) (1:50) Finally, the disc includes three commercials made by Borowczyk in the mid-1960s.

Overall

Borowczyk’s first feature is an engaging, absurdist picture. The staccato editing produces some fascinating juxtapositions, and the film is riddled with irony and dark humour. There are recurring leitmotifs associated with Borowczyk’s work: beaches, the sound of the waves lapping against the shore; sexual repression and the frustration of desire. Borowczyk’s first feature is an engaging, absurdist picture. The staccato editing produces some fascinating juxtapositions, and the film is riddled with irony and dark humour. There are recurring leitmotifs associated with Borowczyk’s work: beaches, the sound of the waves lapping against the shore; sexual repression and the frustration of desire.

Though Théâtre de Monsieur et Madame Kabal is the main feature on this disc, the release bears the title ‘Walerian Borowczyk: Short Films and Animation’, and the shorts that are presented here offer reason enough to justify a purchase. The film, as presented here, is accompanied by a selection of Borowczyk’s shorts and commercials, which begin with ‘The Astronauts’ (1959) and thus omit the shorts that Borowczyk made in Poland. The presentation of the film, and the shorts, is first class, and the featurettes offer a fascinating glimpse into this era of Borowczyk’s career. Combined with Arrow’s other Borowczyk releases, this disc offers one of the most satisfying home video releases of the year, and Arrow should be congratulated on the level of care and attention that is evident throughout all five of the discs contained in the Camera Obscura set. References: Richardson, Michael, 2006: Surrealism and Cinema. Oxford: Berg Thompson, Richard, 1976: ‘Meep, Meep’. In: Nichols, Bill (ed), 1976: Movies and Methods: Volume 1. University of California Press: 126-34

|

|||||

|