|

|

The Film

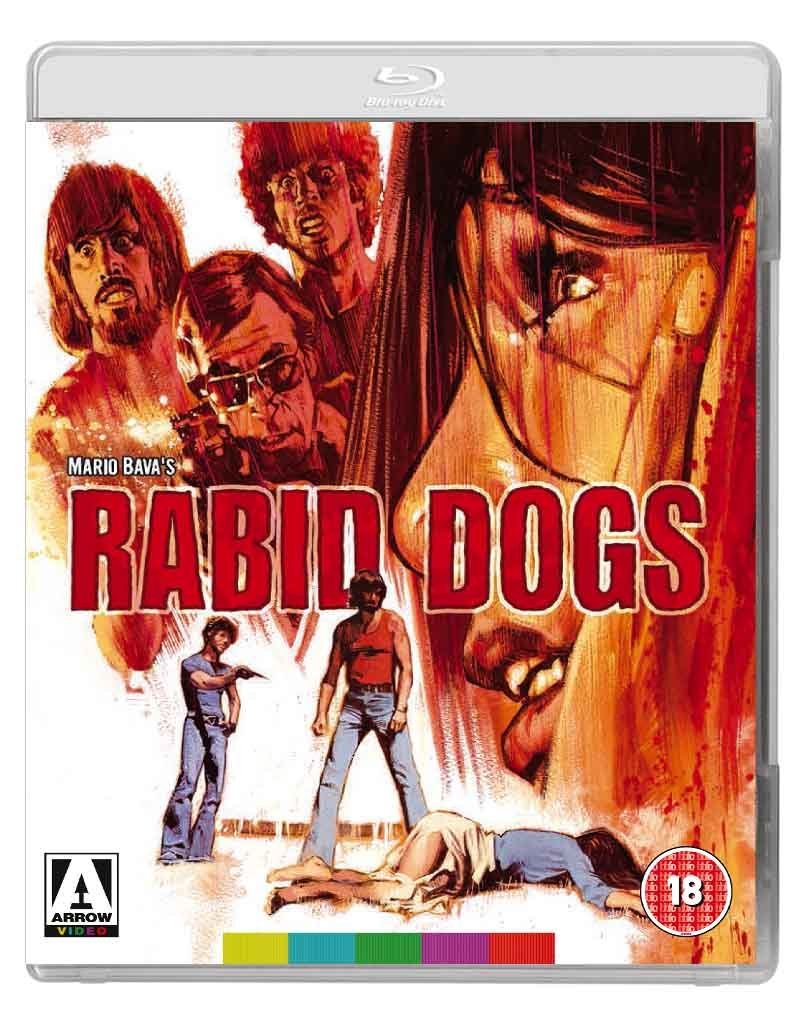

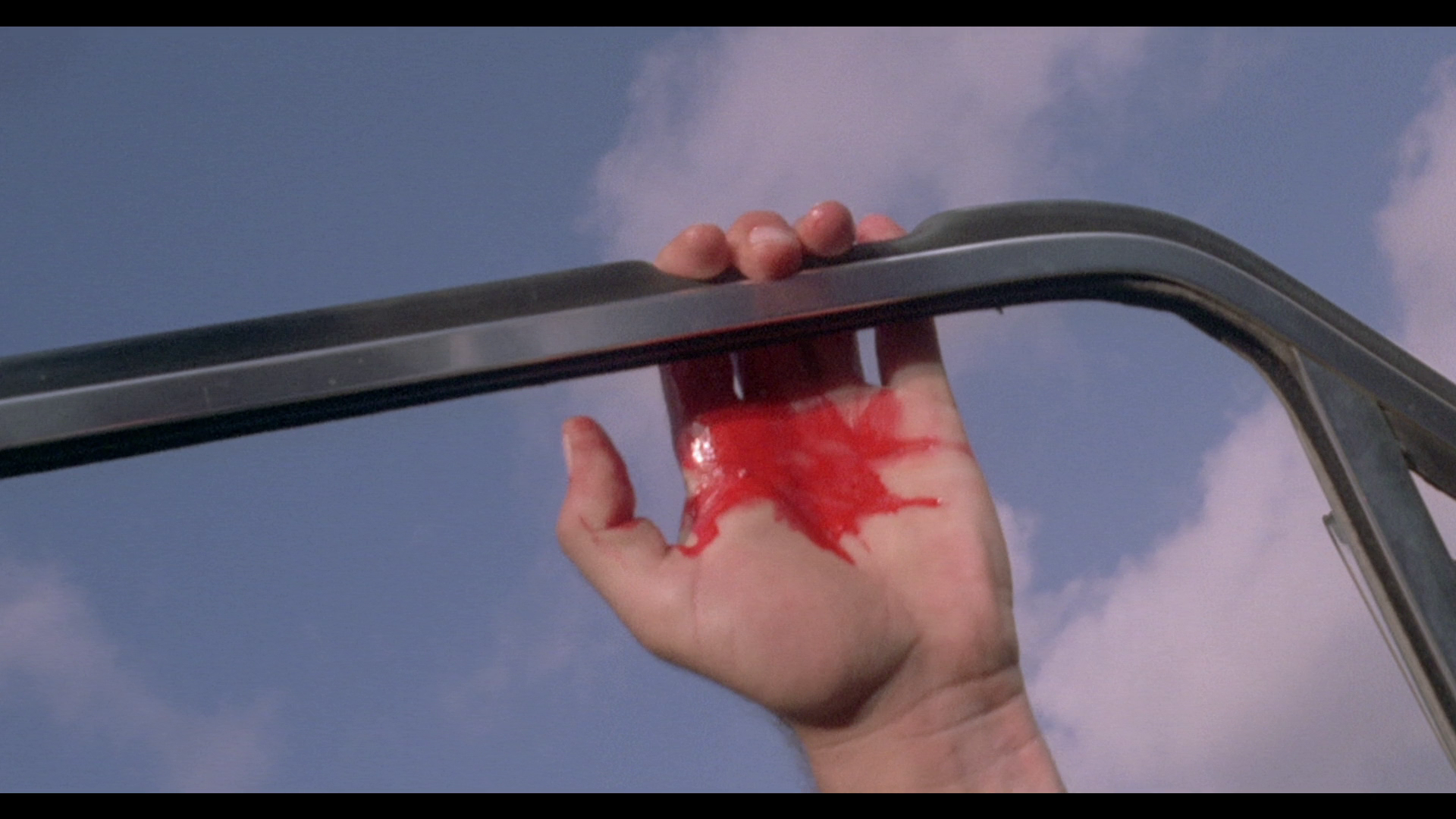

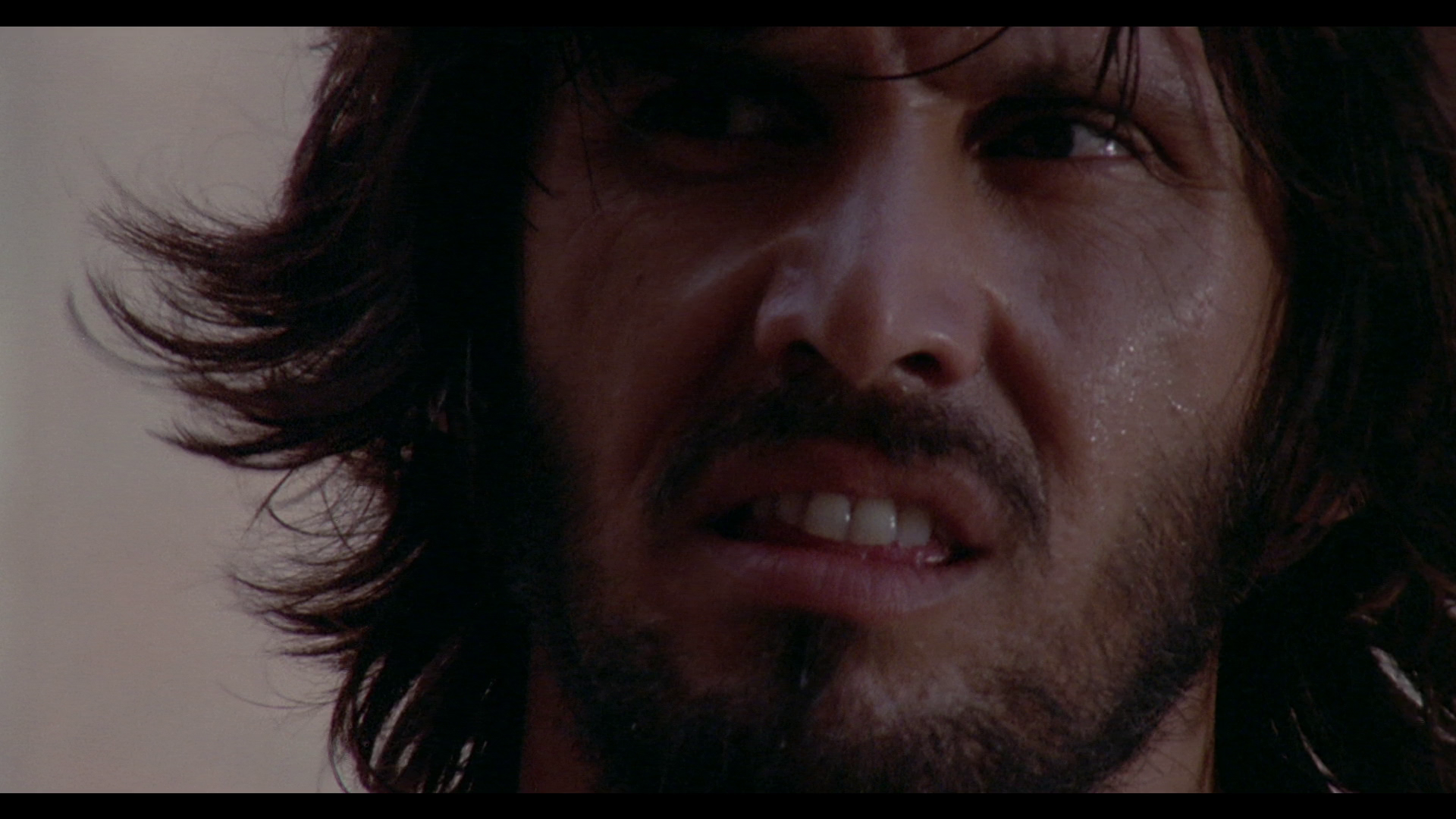

Rabid Dogs (Mario Bava, 1974) Rabid Dogs (Mario Bava, 1974)

Loosely based on a story, ‘Man and Boy’ by Michael J Carroll, originally published in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1971, Mario Bava’s Cani arrabbiati (more widely known in English as Rabid Dogs, but also released under the alternate translation of the Italian title, Wild Dogs) went into production under the working title ‘L’uomo e il bambino’ (‘The Man and the Child’) and has also been listed under the title ‘Semaforo Rosso’, a reference to the red traffic light that results in the meeting of the film’s principal characters. The film marked a change of pace for Bava, whose career as a film director to this point had mostly consisted of the cinema of the ‘fantastique’ – from supernatural horror films such as Operazione Paura (Kill, Baby, Kill, 1966) to science-fiction films (Terrore nello spazio/Planet of the Vampires, 1965) and fantasy-themed pepla (Ercole al centro della terra/Hercules in the Haunted World, 1961). Along the way, he also directed a couple of (rather flat) Westerns all’italiana/Continental Westerns, La strada per Fort Alamo (The Road to Fort Alamo, 1964) and Roy Colt & Winchester Jack (1970). Bava is of course most widely known for his work in cementing the characteristics of the thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with films such as Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964) and Ecologia del delitto (Bay of Blood, 1971). Rabid Dogs, however, represented a very different type of film: a nihilistic contemporary crime picture, absent the elements of mystery and whodunit structure which characterise Bava’s thrilling all’italiana pictures. Rabid Dogs broadly taps into another filone (stream) popular within Italian cinema at the time, that of the poliziesco all’italiana – often referred to in the 1970s by the pejorative label ‘poliziotteschi’, which over time has come to be the most common label used by English-speaking fans of these films (much as the misnomer ‘giallo’ is often used to describe examples of the thrilling all’italiana; or the once-derogative ‘Spaghetti Western’ is used to describe Westerns all’italian). Having some of its roots in film-inchiesta (semidocumentary-style investigation films), such as Francesco Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962), the poliziesco all’italiana had become popular in the late-1960s, gathering steam throughout the 1970s and tapping into the zeitgeist of panics surrounding organised crime and domestic terrorism that followed the Piazza Fontana bombing that took place at the National Agrarian Bank in Milan, 1969; this was an event which marked the beginning of a decade dominated by politically-motivated conflicts between the carabinieri and the so-called ‘Red Brigades’. Films within the poliziesco-all’italiana subgenre very often focused on themes of vigilantism or ‘Dirty Harry’-style cops: for example, La polizia ringrazia (Execution Squad; Steno, 1968), a film which is often labeled as helping to define the thematic focus of subsequent examples of the poliziesco all’italiana, focuses on a group of vigilantes which is executing criminals who can’t be brought to justice within the Italian legal system. Later films often encourage the audience to reflect on and identify with the efforts of solo vigilante cops, in a Dirty Harry mold, who take action where the law cannot: the actor Maurizio Merli (Umberto Lenzi’s Napoli violenta, 1976; Marino Girolami’s Roma violenta, 1975) became a key part of the iconography of this group of films.  Another major subset of films within the poliziesco all’italiana include those which focus on roving groups of banditti, usually depicted in the pictures as amoral members of the peasant class, motivated to a greater extent by jealousy over what the bourgeoisie have which they themselves do not – or, on the flipside, they are sometimes depicted as bourgeois youths who are motivated to commit crime through a profound sense of ennui and a belief in their own entitlement. These films are sometimes (though not always) filtered through the perspective of a police officer investigating the crimes perpetrated by these banditti; this is the case in Romolo Guerreri’s Liberi armati pericolosi (Young, Violent, Dangerous, 1976), for example. Other films within this group focus more heavily on the banditti than on the police investigating their crimes, foregrounding the behaviour of the banditti and, depending on how charitably you feel towards these films, balancing attempts at offering a Dostoevskian social critique with the desire to enable their audience to experience a vicarious thrill through the depiction of the anti-social behaviour perpetrated by the youths: this is arguably the case in a film such as I ragazzi della Roma violenta (Renato Savino, 1976), which focuses on a group of bourgeois youths who identify with Nazi ideology and embark on a spree of rape and murder. Another major subset of films within the poliziesco all’italiana include those which focus on roving groups of banditti, usually depicted in the pictures as amoral members of the peasant class, motivated to a greater extent by jealousy over what the bourgeoisie have which they themselves do not – or, on the flipside, they are sometimes depicted as bourgeois youths who are motivated to commit crime through a profound sense of ennui and a belief in their own entitlement. These films are sometimes (though not always) filtered through the perspective of a police officer investigating the crimes perpetrated by these banditti; this is the case in Romolo Guerreri’s Liberi armati pericolosi (Young, Violent, Dangerous, 1976), for example. Other films within this group focus more heavily on the banditti than on the police investigating their crimes, foregrounding the behaviour of the banditti and, depending on how charitably you feel towards these films, balancing attempts at offering a Dostoevskian social critique with the desire to enable their audience to experience a vicarious thrill through the depiction of the anti-social behaviour perpetrated by the youths: this is arguably the case in a film such as I ragazzi della Roma violenta (Renato Savino, 1976), which focuses on a group of bourgeois youths who identify with Nazi ideology and embark on a spree of rape and murder.

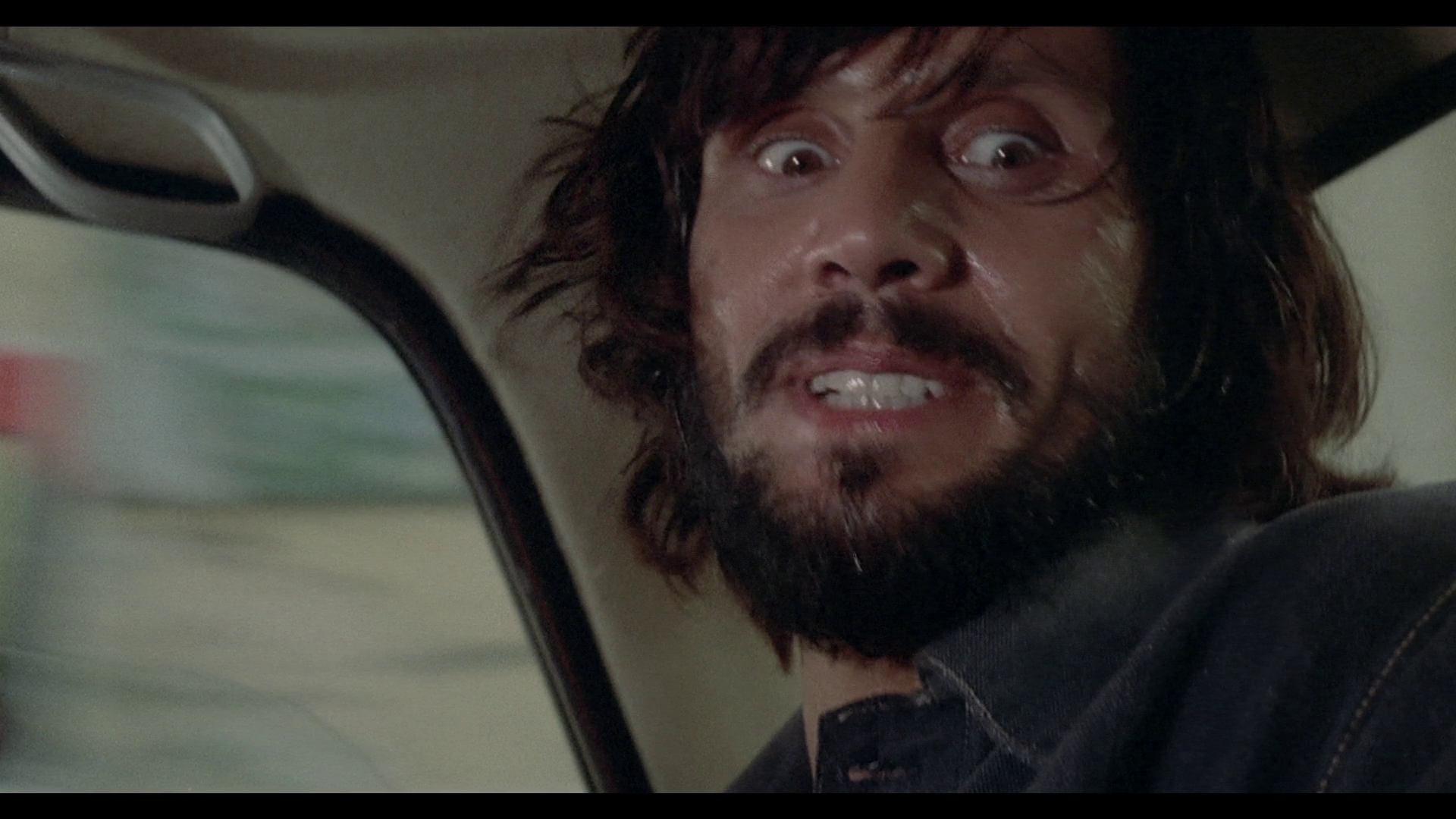

Rabid Dogs roughly conforms to the characteristics of this group of pictures within the poliziesco all’italiana. The title of the film refers to the banditti depicted within its narrative, characterising them as animals (either ‘rabid’ or ‘wild’ dogs, depending on the translation). In the film, the group of banditti is split along class lines: the more erudite and slightly older ‘Dottore’ (‘Doc’, in the English translation; played by Maurice Poli) is the leader of the group; his subordinates Bisturi/‘Blade’ (Aldo Caponi) and Trentadue/‘32’ (Luigi Montefiore) are named, simply, after weapons. These weapons are a switchblade and a .32 calibre revolver, respectively; though underscoring the sexual connotations of the violence they commit, 32 sexually humiliates his female hostage, Maria (Lea Lander), by revealing his penis to her and suggesting his nickname derives from its length in centimetres. After stealing a hundred million lire in wages from a pharmaceutical firm, this group goes ‘on the lam’, taking hostage the urban bourgeois Maria (‘like the Madonna’, 32 notes before comparing her to ‘that actress on TV. The one who never smiles’ – Greta Garbo), who is in town on a shopping trip with her friend, and Riccardo (Riccardo Cucciolla), who is travelling with a sick young boy.  As the film progresses, Bava slowly destablises the stereotypes that are suggested in this brief synopsis: the differences between hostage taker and victim, between hunter and prey, are gradually eroded, as is the archetypal good/evil dualism on which many examples of the poliziesco all’italiana are predicated. Much of the film’s narrative takes place in the confines of Riccardo’s car as it travels along the motorway between Rome and Civitavecchia, with the five adults and the sick young boy cramped within it. As the film progresses, Bava slowly destablises the stereotypes that are suggested in this brief synopsis: the differences between hostage taker and victim, between hunter and prey, are gradually eroded, as is the archetypal good/evil dualism on which many examples of the poliziesco all’italiana are predicated. Much of the film’s narrative takes place in the confines of Riccardo’s car as it travels along the motorway between Rome and Civitavecchia, with the five adults and the sick young boy cramped within it.

Shooting began in either August of 1973 or 1975 (depending on which sources you consult), and Bava’s intention was to shoot the picture in sequence. However, the shooting of the film was problematic: the use of hot lights and the presence of so many people within the vehicle, whose windows had to be shut for the purposes of filming, raised the temperature within the small car to an uncomfortable 120 degrees Fahrenheit. In addition, Al Lettieri, who had been cast as Riccardo, arrived on the set in a drunken state and, owing to this, was eventually replaced in the role by Riccardo Cucciolla, who had to read his lines from pieces of the script that were taped, out of sight of the camera, to parts of the car interior (see Curti, 2013: 116). To compound matters, the producer, Roberto Loyola, financed the film in a piecemeal manner, and production was halted several times owing to a lack of funds and the cheques for the crew’s wages bouncing (see Derdérian, 1994: 131). Finally, Loyola went bankrupt, with some sequences remaining unshot and the film in an unfinished state. Actress Lea Lander managed to acquire the rights to the film in the 1990s, leading to its reconstruction and premiere (as ‘Semaforo Rosso’) at the Mifed festival in 1995 (and eventual release on DVD from Lucertola Media in 1998). Lander’s edit of the film was based on a rough cut put together by Carlo Reali as principal shooting was taking place. For its 1995 release, the film was dubbed and scored with music from recordings put together by Stelvio Cipriani. Various versions circulated on DVD since then, some featuring slightly different opening credits and subtle differences at the conclusion (some featured a still frame of the trunk of the car; others, such as the version of the film contained on the German DVD release from Astro, under the title Wild Dogs, continue this sequence to show the car driving away). Another version was assembled by Alfredo Leone, later amended with the input of Bava’s son Lamberto Bava, which included a new credit sequence, several newly-filmed scenes, different dubbing and a completely different music score; retitled Kidnapped, this version also cuts some footage that was included in the earlier edits of the film.  Roberto Curti notes that, photographically and thematically, Rabid Dogs is markedly different from Bava’s prior films: ‘Gone are the garish colors, otherworldly atmosphere, outlandish shots and tricks’, Curti notes, and in their place is an overwhelming scent ‘of sweat and gasoline’ which is ‘firmly rooted in 1970s Italy’ (op cit.: 116). The absence of police figures within the narrative distance the picture from the majority, though not all, of the poliziesco all’italiana pictures made during the era, and the film as a whole has the aura of ‘a sort of on-the-road variation of a standard Desperate Hours plot’ (ibid.). Roberto Curti notes that, photographically and thematically, Rabid Dogs is markedly different from Bava’s prior films: ‘Gone are the garish colors, otherworldly atmosphere, outlandish shots and tricks’, Curti notes, and in their place is an overwhelming scent ‘of sweat and gasoline’ which is ‘firmly rooted in 1970s Italy’ (op cit.: 116). The absence of police figures within the narrative distance the picture from the majority, though not all, of the poliziesco all’italiana pictures made during the era, and the film as a whole has the aura of ‘a sort of on-the-road variation of a standard Desperate Hours plot’ (ibid.).

As the narrative progresses, Doc – whose name suggests a level of intellect and organisation above that of his colleagues (much as the name ‘Doc’ is used for the protagonist of Jim Thompson’s 1958 novel The Getaway) – becomes increasingly ashamed of the behaviour of 32 and Blade. Whilst their robbery isn’t explicitly politically motivated, Doc acknowledges the class divisions that exist between his group and the bourgeois Riccardo and Maria: ‘Listen. It’s very simple’, Doc says at one point, ‘On one side, there’s us, who want the money. And on the other side, there’s all of you, who are trying to stop us’. The didactic nature of this exchange almost recalls the classic Situationist exercise in detournment, La dialectique peut-elle casser des briques? (Can Dialectics Break Bricks?, 1973), in which a bog standard martial arts film was turned into a subversive picture about class warfare (the proletariats versus the bureaucrats) by dubbing the dialogue with Situationist slogans (‘Bureaucrat! I’m fed up. I’m not gonna kill myself with some stinking job all my life’, a proletariat says at one point; ‘Hmm. You could have a word about that with your union… or perhaps read the Nouvel Observateur?’, a villainous bureaucrat responds).  The journey along the motorway is halted by a series of minor obstacles, of the kind that most bourgeois characters face every day – but which cause Doc, Blade and 32 to sweat with panic at the potential for capture by the police. As they pass through a toll both, for example, they discover that Doc’s ripping up of Riccardo’s ticket results in the necessity of buying another one. The jobsworth toll booth operator placates them with the well-worn line, ‘If it was up to me, I’d let you through’, but insists that they must buy another ticket – if he let one person through without a ticket, he says, he would have to do it for everyone. Not long after, Riccardo accidentally bumps into the back of another car. ‘I hope you’re not one of those people who don’t have insurance’, the irate driver of the other vehicle rants. Doc finds that he must also hand over some of the stolen loot to pacify this man. At a service station where the group stop to buy supplies, Riccardo and 32 are followed into the public lavatories by a janitor, who seems to consider the pair to be guilty of cottaging; later, whilst waiting in the queue to pay for their goods, Riccardo and 32 are accosted by a female acquaintance of Riccardo’s. The blowsy redhead causes Riccardo to panic, and 32 tries to impress the woman, in a scene that is deeply blackly comic, crosscut with Blade and Doc's escalating sense of panic that they will be found out. Later in the film, Riccardo’s car runs out of petrol, and the group stop at a petrol station where another jobsworth worker initially refuses to serve them because he is on his lunch break: he’s been robbed before and is therefore wary. ‘We have to follow strict rules’, the worker protests. As Riccardo’s car drives away, Doc and Riccardo having persuaded the man to allow them to fill the car with petrol, the worker watches the vehicle recede into the distance with some concern on his face, clearly reflecting on the unusual behaviour of the group. Bava frames the worker with the forecourt’s telephone just behind him, visually reinforcing the possibility of this man calling the police and signaling for help. This makes the worker’s decision to turn his back on the scene, ignoring the strangeness of what he has witnessed in favour of returning to his coveted lunch break, even more pointed. After this, Blade insists that the car stop by a farm, where he sneaks into a field and steals some grapes. He is stopped by a farmer. ‘I’m sorry, but I really needed them’, Blade protests, before giving the farmer 50,000 lire in payment for the grapes. These scenarios are suggestive of the small obstacles that those within the bourgeoisie face every day and which gradually eat away at our finances, rendered absurd by the panic exhibited by Doc’s band of thieves in response to these 'normal' scenarios that undercut and penetrate the hardboiled exterior of the group - all the while eating away at the loot Doc's group has obtained (which, Riccardo observes at one point in the film - much to Doc's chagrin - isn't really an awful lot of money). The journey along the motorway is halted by a series of minor obstacles, of the kind that most bourgeois characters face every day – but which cause Doc, Blade and 32 to sweat with panic at the potential for capture by the police. As they pass through a toll both, for example, they discover that Doc’s ripping up of Riccardo’s ticket results in the necessity of buying another one. The jobsworth toll booth operator placates them with the well-worn line, ‘If it was up to me, I’d let you through’, but insists that they must buy another ticket – if he let one person through without a ticket, he says, he would have to do it for everyone. Not long after, Riccardo accidentally bumps into the back of another car. ‘I hope you’re not one of those people who don’t have insurance’, the irate driver of the other vehicle rants. Doc finds that he must also hand over some of the stolen loot to pacify this man. At a service station where the group stop to buy supplies, Riccardo and 32 are followed into the public lavatories by a janitor, who seems to consider the pair to be guilty of cottaging; later, whilst waiting in the queue to pay for their goods, Riccardo and 32 are accosted by a female acquaintance of Riccardo’s. The blowsy redhead causes Riccardo to panic, and 32 tries to impress the woman, in a scene that is deeply blackly comic, crosscut with Blade and Doc's escalating sense of panic that they will be found out. Later in the film, Riccardo’s car runs out of petrol, and the group stop at a petrol station where another jobsworth worker initially refuses to serve them because he is on his lunch break: he’s been robbed before and is therefore wary. ‘We have to follow strict rules’, the worker protests. As Riccardo’s car drives away, Doc and Riccardo having persuaded the man to allow them to fill the car with petrol, the worker watches the vehicle recede into the distance with some concern on his face, clearly reflecting on the unusual behaviour of the group. Bava frames the worker with the forecourt’s telephone just behind him, visually reinforcing the possibility of this man calling the police and signaling for help. This makes the worker’s decision to turn his back on the scene, ignoring the strangeness of what he has witnessed in favour of returning to his coveted lunch break, even more pointed. After this, Blade insists that the car stop by a farm, where he sneaks into a field and steals some grapes. He is stopped by a farmer. ‘I’m sorry, but I really needed them’, Blade protests, before giving the farmer 50,000 lire in payment for the grapes. These scenarios are suggestive of the small obstacles that those within the bourgeoisie face every day and which gradually eat away at our finances, rendered absurd by the panic exhibited by Doc’s band of thieves in response to these 'normal' scenarios that undercut and penetrate the hardboiled exterior of the group - all the while eating away at the loot Doc's group has obtained (which, Riccardo observes at one point in the film - much to Doc's chagrin - isn't really an awful lot of money).

Video

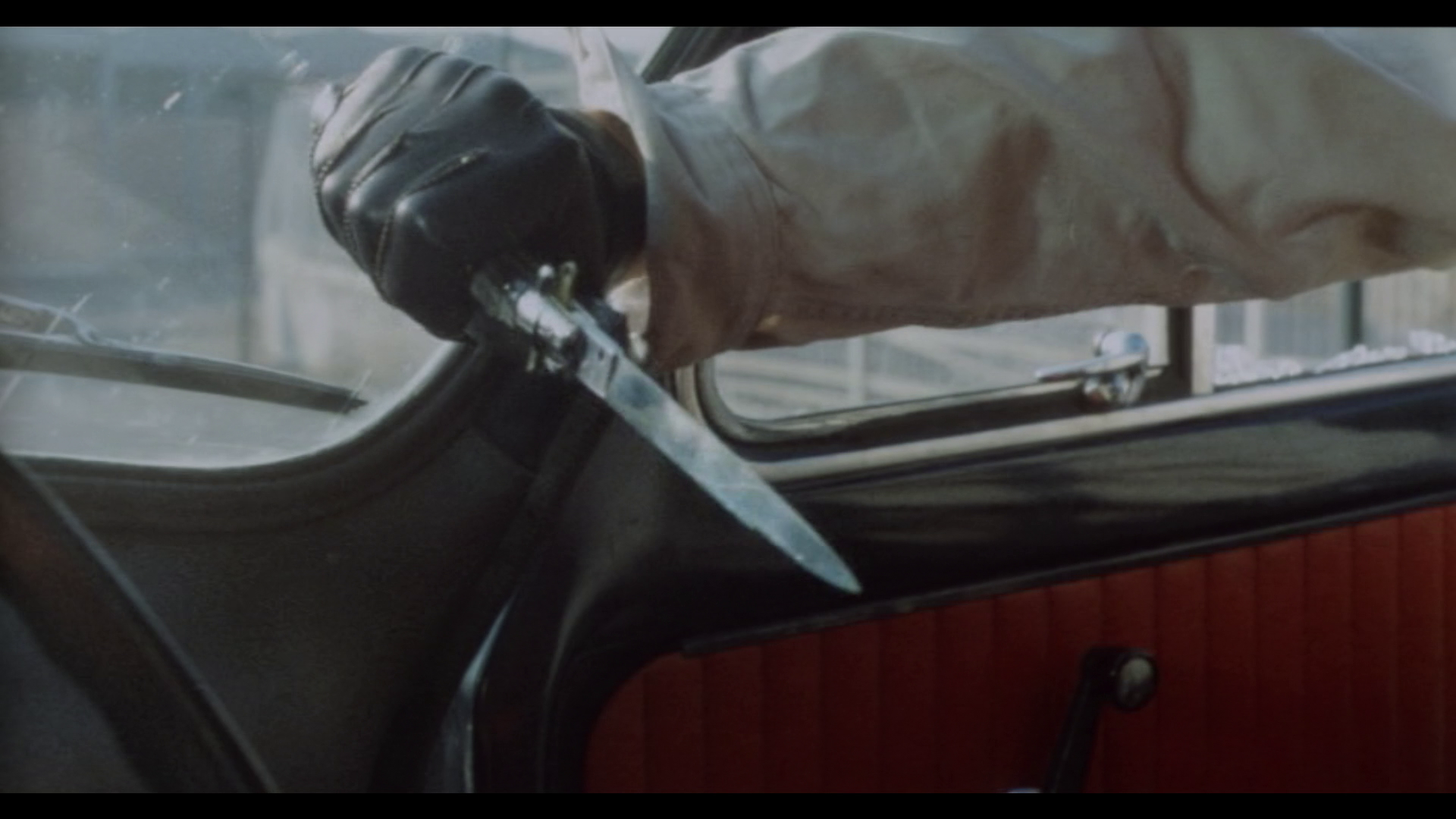

Much of the film was shot inside Riccardo’s car, with the sense of claustrophobia being heightened by the cramped compositions and the use of lenses with short focal lengths. Much of the film was shot inside Riccardo’s car, with the sense of claustrophobia being heightened by the cramped compositions and the use of lenses with short focal lengths.

As noted above, there are several different edits of the film in existence. Lamberto Bava’s reworked version, Kidnapped, is the one that has been released on Blu-ray previously, from Kino in the US and by Raro in Italy. Arrow’s release contains both the Kidnapped version and the Rabid Dogs edit (identical in content to the Lucertola Media release, and minus the final shot of the car driving away that was contained in the German release from Astro). The Rabid Dogs edit is far superior: the Kidnapped edit contains some new footage which jars with the rest of the film, abbreviates some sequences, and most damagingly omits Stelvio Cipriani’s relentless, driving score. In their attempts to present the Rabid Dogs edit in HD for the first time, Arrow faced some obstacles, discovering that the original negative for the film no longer exists, having been used to create the Kidnapped version. To present the Rabid Dogs edit in HD therefore required Arrow to create a composite version, using the HD presentation of Kidnapped as a base and editing into it the unique footage from the Rabid Dogs cut of the film (taken from a standard definition source). Consequently, throughout the Rabid Dogs edit there are numerous sequences which cut back and forth between HD footage and SD inserts – showing just how impressive the HD presentation is in terms of contrast and detail. There’s an incredible level of detail in the HD presentation, with a real sense of depth to the image – enhancing the stench of sweat and petrol that Curti says is a key element of the film. The picture throughout has an organic, film-like appearance, with no harmful evidence of digital tinkering. The encode to disc is strong too. It’s a shame that the Rabid Dogs edit could not be presented entirely in HD, but regardless of the noticeable ‘jump’ between the HD footage that makes up the bulk of the film and the SD inserts, it’s a hugely impressive presentation, and certainly the best way to watch the film. Both versions of the film are in an aspect ratio of 1.85:1 (which would seem to be the intended aspect ratio), and are presented using the AVC codec. The Kidnapped edit, running 95:29 mins, takes up 17.7Gb on the disc; the Rabid Dogs edit, on the other hand, runs for 95:50 mins and takes up 19.4Gb on the disc. A comparison of the HD footage with the SD inserts can be found below. (More large screen grabs can be found at the bottom of this review.) HD:

SD Insert:

HD:

SD Insert:

Audio

Audio is presented, in Italian, via a LPCM 2.0 stereo track, with optional English subtitles. The Rabid Dogs track lacks range in comparison with the Kidnapped track: the latter offers a more rich soundscape, and the former feels ‘crushed’ in comparison. Nevertheless, both audio tracks are perfectly acceptable. The subtitles don’t necessarily represent an accurate translation of the Italian dialogue. The Italian dialogue is laced with profanities, which is unusual for a Bava film, but these aren’t always translated accurately in the subtitling, which tends to use stronger English-language words in their place, peppering the dialogue with ‘fucks’, etc, that aren’t in the Italian track. On the other hand, the subtitling renders the names of the characters more effectively than the subtitles included on the Anchor Bay DVD released in the late-2000s. (Arrow have included a blog post on the subtitling of this release here.)

Extras

The disc includes an audio commentary by Tim Lucas. This commentary is the same one which appeared on the US DVD release from Anchor Bay. Like the majority of Lucas’ tracks, it’s engaging and informative, driven by Lucas’ enthusiasm for the film. The disc includes an audio commentary by Tim Lucas. This commentary is the same one which appeared on the US DVD release from Anchor Bay. Like the majority of Lucas’ tracks, it’s engaging and informative, driven by Lucas’ enthusiasm for the film.

The disc also includes two featurettes: - ‘End of the Road: Making Rabid Dogs and Kidnapped’ (16:33). This featurette, presented in Italian and English, with burnt-in English subtitles for the Italian language segments, features interviews with Lamberto Bava, Alfredo Leone and Lea Lander. - ‘Bava and Eurocrime: An Interview with Umberto Lenzi’ (9:00). This interview with Lenzi, one of the key names within the poliziesco all’italiana, reflects on the relationship between that subgenre and Bava’s film. The interview is presented in Italian with burnt-in English subtitles. ‘Semaforo Rosso’ opening credits (1:31). As suggested by the title, this is simply the opening credits for the ‘Semaforo Rosso’ version of the film.

Overall

Some Italian sources suggest Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) is an ironic reimagining of Rabid Dogs (see, for example, Grande, 2009: 28; Giordano, 2012: 34). However, the similarities lie in the use of the word ‘dogs’ within the title as an index of the animalistic, pack-like behaviour of each films’ group of protagonists. Nevertheless, Rabid Dogs has a very contemporary ‘feel’: the opening heist is depicted via some brutal cross-cutting that is reminiscent of the pivotal heist in Michael Tuchner’s Villain (1971), for example. It’s a superb, exciting film, made even more so by the claustrophobic photography. (My only reservation, perhaps, is with the ‘modernisation’ of the dialogue within the English subtitles; I can see the justification for this, but I’m not sure it was the best route to take and would liked to have seen a more ‘accurate’ subtitle track presented as an optional alternative.) Some Italian sources suggest Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs (1992) is an ironic reimagining of Rabid Dogs (see, for example, Grande, 2009: 28; Giordano, 2012: 34). However, the similarities lie in the use of the word ‘dogs’ within the title as an index of the animalistic, pack-like behaviour of each films’ group of protagonists. Nevertheless, Rabid Dogs has a very contemporary ‘feel’: the opening heist is depicted via some brutal cross-cutting that is reminiscent of the pivotal heist in Michael Tuchner’s Villain (1971), for example. It’s a superb, exciting film, made even more so by the claustrophobic photography. (My only reservation, perhaps, is with the ‘modernisation’ of the dialogue within the English subtitles; I can see the justification for this, but I’m not sure it was the best route to take and would liked to have seen a more ‘accurate’ subtitle track presented as an optional alternative.)

The Kidnapped re-edit is disappointing, but the Rabid Dogs cut is as impressive as ever – and it’s to Arrow’s credit that they have gone to such lengths to present this version of the film in the best way possible. The strengths of the HD presentation are evidenced in the juxtaposition between the HD footage that makes up the bulk of the Rabid Dogs cut with the SD inserts. It’s a hugely impressive presentation. The disc also includes some very good contextual material, including Lucas’ previously-released commentary and two featurettes. For Bava fans, it seems to have been a long time in the making, but Arrow’s Rabid Dogs Blu-ray release is worth the wait. This is by far the best release that this excellent film has had to date.  Bibliography: Curti, Roberto, 2013: Italian Crime Filmography: 1968-1980. London: McFarland Derdérian, Stephane, 1994: ‘Mario Bava, libre artisan du cinéma de la peur’. In: Leutrat, Jean-Louis (ed), 1994: Mario Bava. Les éditions Céfal Giordano, Biagio, 2012: Uno sguardo sul cinema. Morrisville: Lulu Enterprise Grande, Allesandro, 2009: La produzione del cinema Italiano oggi. Lulu.com

|

|||||

|