|

|

Girl Who Knew Too Much AKA La Ragazza che sapeva troppo AKA The Evil Eye (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (27th November 2014). |

|

The Film

The Girl Who Knew Too Much (Mario Bava, 1963) The Girl Who Knew Too Much (Mario Bava, 1963)

Mario Bava’s 1963 film La ragazza che sapeva troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much, released in Britain and America as The Evil Eye) is usually cited as the film which began the giallo (plural: gialli), a filone (‘stream’) within Italian cinema which became increasingly popular towards the end of the 1960s. This particular filone took its name from the lurid yellow (giallo) covers of the whodunits and thrillers (by authors such as Fredric Brown, John Dickson Carr and Cornell Woolrich) published by Mondadori, under the imprint I libri gialli, later to become I gialli Mondadori, in the 1930s and beyond. Though to English-speaking fans of the films, the label giallo usually refers to the very Italian thrillers associated with filmmakers like Mario Bava, Sergio Martino and Dario Argento; to Italian audiences, the word giallo denotes any type of thriller, regardless of its place of production. So for Italian audiences, Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960), Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971) or Sidney Lumet’s adaptation of Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express (1974) may be labeled as gialli. Italian audiences usually refer to the peculiarly Italian thrillers of Bava, Martino and Argento, etc, as either gialli all’italiana or examples of the thrilling all’italiana (‘Italian-style thriller’). Unlike English-speaking fans, Italian audiences also tend to include examples of the poliziesco all’italiana (Italian-style police films, often referred to as poliziotteschi, a label originally used pejoratively but later accepted by fans, much like the phrase ‘Spaghetti Westerns’) in discussions of gialli all’italiana, and of course in films such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?; Massimo Dallamano, 1974) the Italian-style police films and Italian-style thrillers often overlap in ways which highlight that the dualism between these two groups of cinematic thrillers is a false one. However, the poliziesco all’italiana films tend to be differentiated from examples of the thrilling all’italiana in terms of the former’s focus on police investigations and elements of the police procedural, whereas the latter is usually seen as focusing on amateur sleuths and combining traditional thriller elements (notably the narrative conventions of the ‘whodunnit’) with the iconography of horror films.  Whilst The Girl Who Knew Too Much wasn’t the first Italian thriller (the label had previously been applied to Luchino Visconti’s 1943 Ossessione, an adaptation of James M Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, for example), Bava’s picture was the film that consolidated the elements of the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana. (The first Italian detective novel, Il mio cadavere – by Francesco Mastriani, published in 1852 – is sometimes claimed to contain the same fusion of psychological thriller and horror that characterises the later thrilling all’italiana films of people like Bava and Argento.) Gino Moliterno cites Bava’s film as establishing the narrative template that would define many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana: principally, ‘the story of an innocent eyewitness to a violent murder who takes on the role of amateur detective in order to track down the killer and, in the process, becomes one of the killer’s main targets’ (2009: 151). This basic narrative model would form a core element of the Italian thrillers of the late 1960s and 1970s, and would reappear in films such as Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1969) and Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1974), Luigi Bazzoni’s Giornata nera per l’ariete (The Fifth Cord, 1971), Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House with Laughing Windows, 1975) and Sergio Martino’s Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh, 1971) and Tutti i colori del buio (All the Colors of the Dark, 1972). Bava’s next entry into the thrilling all’italiana, Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), would establish one of the Italian thriller’s most lasting visual paradigms (a killer clad in a black trenchcoat and fedora, and wearing black leather gloves), as well as the emphasis on set-pieces that depict murder as a form of Sadean spectacle that would come to the fore in Argento’s gialli (and would also work its way into American bodycount/stalk-and-slash/slasher films during the late-1970s and 1980s). Whilst The Girl Who Knew Too Much wasn’t the first Italian thriller (the label had previously been applied to Luchino Visconti’s 1943 Ossessione, an adaptation of James M Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice, for example), Bava’s picture was the film that consolidated the elements of the thrilling all’italiana/giallo all’italiana. (The first Italian detective novel, Il mio cadavere – by Francesco Mastriani, published in 1852 – is sometimes claimed to contain the same fusion of psychological thriller and horror that characterises the later thrilling all’italiana films of people like Bava and Argento.) Gino Moliterno cites Bava’s film as establishing the narrative template that would define many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana: principally, ‘the story of an innocent eyewitness to a violent murder who takes on the role of amateur detective in order to track down the killer and, in the process, becomes one of the killer’s main targets’ (2009: 151). This basic narrative model would form a core element of the Italian thrillers of the late 1960s and 1970s, and would reappear in films such as Dario Argento’s L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo (The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1969) and Profondo rosso (Deep Red, 1974), Luigi Bazzoni’s Giornata nera per l’ariete (The Fifth Cord, 1971), Pupi Avati’s La casa dalle finestre che ridono (The House with Laughing Windows, 1975) and Sergio Martino’s Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs Wardh, 1971) and Tutti i colori del buio (All the Colors of the Dark, 1972). Bava’s next entry into the thrilling all’italiana, Sei donne per l’assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), would establish one of the Italian thriller’s most lasting visual paradigms (a killer clad in a black trenchcoat and fedora, and wearing black leather gloves), as well as the emphasis on set-pieces that depict murder as a form of Sadean spectacle that would come to the fore in Argento’s gialli (and would also work its way into American bodycount/stalk-and-slash/slasher films during the late-1970s and 1980s).

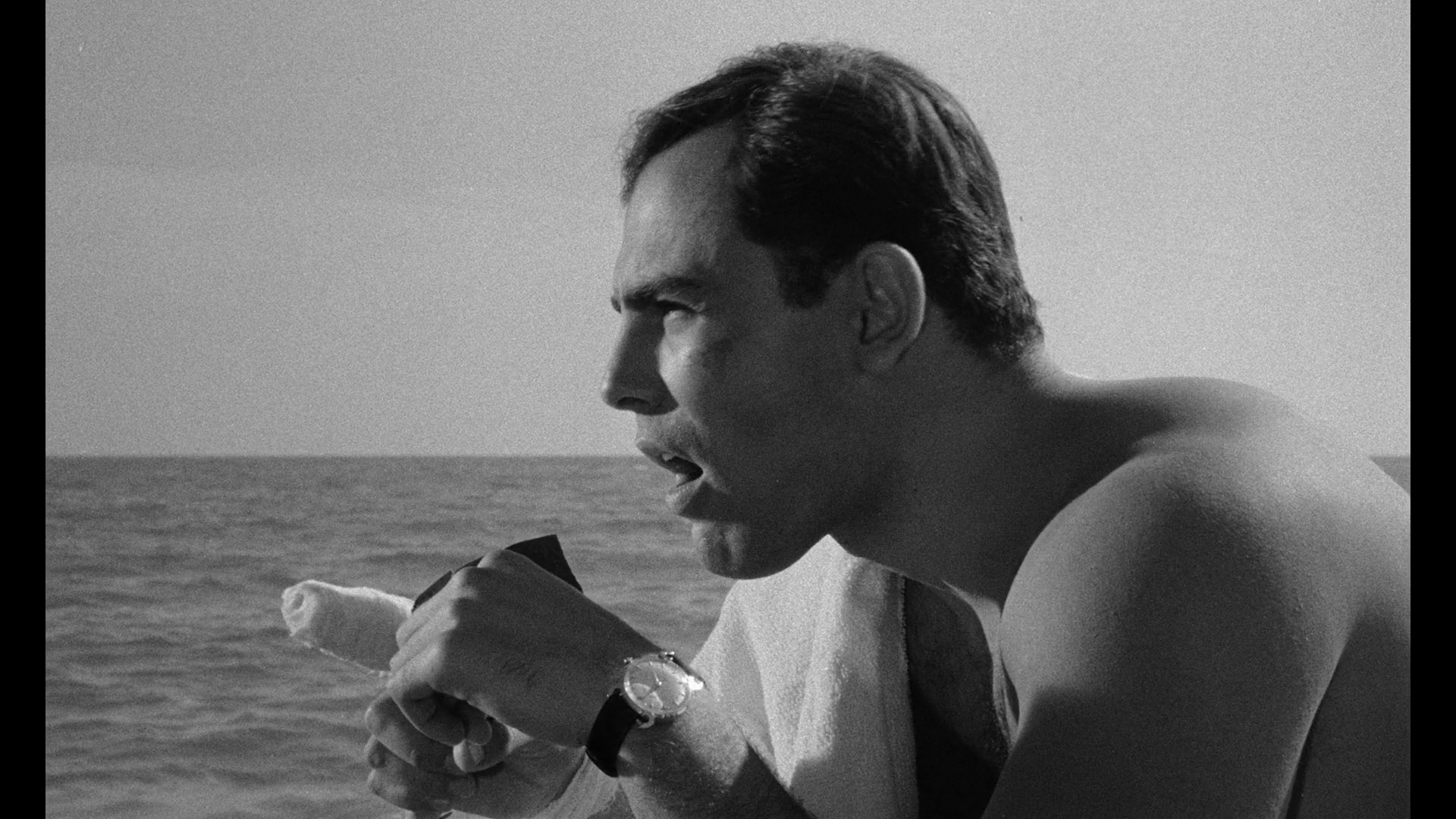

Where many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana would make strong use of colour photography (Bava’s Blood and Black Lace, for example, features an expressive use of primary colours), The Girl Who Knew Too Much was shot by Bava in monochrome, with heavy use of chiaroscuro lighting.  The film focuses on Nora (Leticia Román), a 20 year old American student who, as the film begins, is travelling via aeroplane to Rome, to stay with her elderly Aunt Ethel (Chana Coubert). On board the plane, she is offered a packet of cigarettes by a man who, upon arrival at the airport in Rome, is arrested by police for smuggling into the country cigarettes laced with marijuana. (This is a plot point which is omitted in the version of the film put together by AIP for distribution in America and Britain under the title The Evil Eye.) At Ethel’s house, Nora is introduced to Marcello Bassi (John Saxon), her aunt’s doctor. However, that night Aunt Ethel sadly expires and, seeking help, Nora flees from the house. On the Spanish Steps (the Scalinata della Trinità dei Monti), Nora is knocked to the ground by a purse-snatcher. Concussed, she lapses into unconsciousness, briefly awakening to witness what seems to be a murder: a woman stabbed in the back by a mysterious man. In the morning, the unconscious Nora comes to the attention of a policeman, who assumes her to be a drunk. Nora is admitted to hospital, where she encounters Dr Bassi, who manages to persuade the doctors in charge of her care that she is neither a drunk nor a prostitute – which seems to be their belief, given the circumstances in which she was found. The film focuses on Nora (Leticia Román), a 20 year old American student who, as the film begins, is travelling via aeroplane to Rome, to stay with her elderly Aunt Ethel (Chana Coubert). On board the plane, she is offered a packet of cigarettes by a man who, upon arrival at the airport in Rome, is arrested by police for smuggling into the country cigarettes laced with marijuana. (This is a plot point which is omitted in the version of the film put together by AIP for distribution in America and Britain under the title The Evil Eye.) At Ethel’s house, Nora is introduced to Marcello Bassi (John Saxon), her aunt’s doctor. However, that night Aunt Ethel sadly expires and, seeking help, Nora flees from the house. On the Spanish Steps (the Scalinata della Trinità dei Monti), Nora is knocked to the ground by a purse-snatcher. Concussed, she lapses into unconsciousness, briefly awakening to witness what seems to be a murder: a woman stabbed in the back by a mysterious man. In the morning, the unconscious Nora comes to the attention of a policeman, who assumes her to be a drunk. Nora is admitted to hospital, where she encounters Dr Bassi, who manages to persuade the doctors in charge of her care that she is neither a drunk nor a prostitute – which seems to be their belief, given the circumstances in which she was found.

At Ethel’s funeral, Nora is introduced to Laura Torrani (Valentina Cortese), who lives near the Spanish Steps. Laura asks Nora to housesit for her, whilst Laura leale the country to visit her husband, who works in Bern. Whilst staying in Laura’s house, Nora enlists the help of Bassi in investigating the murder she believes she witnessed. They soon discover that Laura’s sister, Emily Craven, was murdered several years earlier, in a series of crimes dubbed the ‘alphabet murders’, owing to the surnames of the victims beginning with consecutive letters of the alphabet – and Nora’s last name is Davis, which Nora believes may make her the killer’s next target. The clock is set against Nora, who with Bassi – and, later, a former journalist, Landini (Dante DiPaolo) – desperately attempts to uncover the identity of the murderer.  Like many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana, The Girl Who Knew Too Much emphasises the ‘otherness’ of its protagonist: like the American writer Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) in Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, for example, Nora is a cultural outsider. At the beginning of the film, she arrives in Rome via aeroplane, reading a lurid thriller (a giallo entitled The Knife) during the flight. Needham has suggested that this opening sequence foregrounds the ‘literary origins’ of the thrilling all’italiana ‘through mise-en-abime’, whilst also establishing a number of tropes of later examples of the Italian thriller: ‘the foreigner coming to/being in Italy; the obsession with travel and tourism not only as a mark of the newly emerging European jet set (consider how many gialli begin or end in airports), but representative of Italian cinema’s selling of its own “Italian-ness” through tourist hotspots… and of course fashion and style’ (quoted in Mendik, 2014: 391; ellipsis in original). As Xavier Mendik has noted, the motif of fashion would be emphasised in Blood and Black Lace, which focuses on a series of murders committed within the world of haute couture (ibid.). Whilst containing some ‘travelogue’ elements (Bassi takes Nora on a tour of Rome’s major tourist destinations), in its reconfiguration of the landscape of Rome as a site of murder and distrust Bava’s film offers a depiction of modern Italian life that differed from most films set in Italy (and especially, Rome): for example, Delmer Daves’ 1962 romantic picture Rome Adventure. Like many later examples of the thrilling all’italiana, The Girl Who Knew Too Much emphasises the ‘otherness’ of its protagonist: like the American writer Sam Dalmas (Tony Musante) in Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, for example, Nora is a cultural outsider. At the beginning of the film, she arrives in Rome via aeroplane, reading a lurid thriller (a giallo entitled The Knife) during the flight. Needham has suggested that this opening sequence foregrounds the ‘literary origins’ of the thrilling all’italiana ‘through mise-en-abime’, whilst also establishing a number of tropes of later examples of the Italian thriller: ‘the foreigner coming to/being in Italy; the obsession with travel and tourism not only as a mark of the newly emerging European jet set (consider how many gialli begin or end in airports), but representative of Italian cinema’s selling of its own “Italian-ness” through tourist hotspots… and of course fashion and style’ (quoted in Mendik, 2014: 391; ellipsis in original). As Xavier Mendik has noted, the motif of fashion would be emphasised in Blood and Black Lace, which focuses on a series of murders committed within the world of haute couture (ibid.). Whilst containing some ‘travelogue’ elements (Bassi takes Nora on a tour of Rome’s major tourist destinations), in its reconfiguration of the landscape of Rome as a site of murder and distrust Bava’s film offers a depiction of modern Italian life that differed from most films set in Italy (and especially, Rome): for example, Delmer Daves’ 1962 romantic picture Rome Adventure.

In the Italian version, the third person narration by a male voice offers a fascinating pastiche of the hard-boiled narration associated with the literary gialli of which, in the opening sequence, Nora is shown to be a fan. ‘This is a story of a vacation’, the narrator tells us as the film opens: ‘A vacation in Rome, the dream destination of any American between the age of sixteen and seventy’. About Nora, the narrator tells us, ‘Young, full of life, romantic. She satisfied her desire to escape reality by reading murder mysteries’. The narrator offers insight into Nora’s decisions. On her choice not to inform the police of a telephone call she receives, whilst staying in the Torrani house, that threatens ‘Nora Davis, “D” as in “Death”?’, the narrator tells us ‘Nora had told no one about the phone call. It was useless for them to try and comfort her. Only the truth at this point could restore her sleep. And she needed to look for that truth alone, even at the risk of her life’. When Nora sets a trap for the ‘alphabet killer’ by layering the floor of the hallway with talcum powder and tying string across various parts of the entrance, the narrator explains these actions to us: ‘An idea. A single idea with which to protect herself. She appealed to her old friends, the murder mysteries. She appealed to Wallace, to Mickey Spillane, to Agatha Christie. Talcum powder! That’s right: talcum powder [….] [which is] notoriously slippery’. In the American version, which lacks any narration in this sequence, what precisely Nora is doing in this sequence is far more ambiguous.  The American version replaces the male third-person narration with a first-person narration from Nora’s perspective, an inner monologue which throws focus on Nora’s romantic daydreams and the romantic potential of her friendship with Dr Bassi. Over her arrival in Roma, Nora narrates: ‘A couple of hours in Roma and I’ve already had my hand kissed twice’. Later, when meeting Bassi, Nora reflects in her voiceover: ‘Ah, Dr Bassi. Marcello Bassi. I guess he has to kiss hands because he’s Italian. But he kissed mine twice. I wonder if that means anything’. The American version replaces the male third-person narration with a first-person narration from Nora’s perspective, an inner monologue which throws focus on Nora’s romantic daydreams and the romantic potential of her friendship with Dr Bassi. Over her arrival in Roma, Nora narrates: ‘A couple of hours in Roma and I’ve already had my hand kissed twice’. Later, when meeting Bassi, Nora reflects in her voiceover: ‘Ah, Dr Bassi. Marcello Bassi. I guess he has to kiss hands because he’s Italian. But he kissed mine twice. I wonder if that means anything’.

Nora’s love of mystery novels is used against her when she tries to tell the police about the murder she has apparently witnessed: after telling this tale of events to Dr Fachetti, a police detective, Nora is asked if she reads gialli. When Nora responds in the positive, Fachetti suggests she may have imagined the whole thing before telling her not to read any more mystery novels. (Given the circumstances in which she is discovered by the policeman on the Spanish Steps, the morning after the murder, she is also accused of being a ‘mythomaniac’ and a drunk.) Bassi is initially no less skeptical, suggesting that the death of Ethel and the mugging that Nora experiences on the Spanish Steps may have led her to imagine the more dramatic scenario of the girl’s murder. Nora’s response to these claims is to assert, ‘It’s been a long chain of terrible events. Real or imaginary, it matters little’. Meanwhile, expressing Nora’s thoughts (or at least claiming to), the male narrator suggests that she could have experienced a psychic vision. These claims are given ironic validation in a typically Bava-esque playful scene right at the end of the film when Nora, having survived her ordeal, wonders whether the whole thing has been a hallucination caused by smoking the marijuana-laced cigarettes given to her, in the opening sequence, by the man on the plane: ‘What if it was all a dream?’, she wonders. With this, Bava threatens to destabilise our perception of everything that has gone before – but he doesn’t linger on the question, instead leaving it to resonate in the mind of the viewer. The English-dubbed version changes this significantly, by removing the references to the marijuana-laced cigarettes at the start of the film (in this cut of the film, Nora is shown accepting the cigarettes, and the man is shown to be arrested upon the plane’s arrival in Rome – but we are not told why he has been arrested.)  This disc includes both the original Italian version, in Italian with optional English subtitles (with a running time of 85:38 minutes) and The Evil Eye, the English-dubbed version, complete with new Les Baxter score, prepared by AIP (which runs for 92:15 mins).

Video

Both cuts of the film take up approximately 21Gb of space on the disc each. The Italian cut is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1, whilst the English-dubbed version is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The Italian version features a little more information at the top and bottom of the frame, making the compositions within the English-dubbed version seeming a little more cramped along the vertical axis; but the difference is pretty much negligible. Both versions have an organic, film-like appearance. The Italian cut demonstrates some intermittent damage – nothing too distracting, but a shot of Nora exiting a lift (at 46 minutes into the film) contains some bad vertical scratches, and there are also a couple of very minor instances of what seems to be telecine wobble. By contrast, the presentation of the English cut is cleaner and more free of damage and debris. However, on the other hand the Italian cut seems to have slightly stronger contrast levels, which shows off the chiaroscuro lighting nicely: for example in the sequence in which Nora is shot in silhouette, a halo of light around her, as she stands at Ethel’s bedside. Both cuts of the film take up approximately 21Gb of space on the disc each. The Italian cut is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1, whilst the English-dubbed version is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.78:1. The Italian version features a little more information at the top and bottom of the frame, making the compositions within the English-dubbed version seeming a little more cramped along the vertical axis; but the difference is pretty much negligible. Both versions have an organic, film-like appearance. The Italian cut demonstrates some intermittent damage – nothing too distracting, but a shot of Nora exiting a lift (at 46 minutes into the film) contains some bad vertical scratches, and there are also a couple of very minor instances of what seems to be telecine wobble. By contrast, the presentation of the English cut is cleaner and more free of damage and debris. However, on the other hand the Italian cut seems to have slightly stronger contrast levels, which shows off the chiaroscuro lighting nicely: for example in the sequence in which Nora is shot in silhouette, a halo of light around her, as she stands at Ethel’s bedside.

Both versions offer a significant improvement over previously available DVD releases and should please videophiles. NB. Some larger screengrabs, from the Italian version, are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio on the Italian version is presented via a LPCM 2.0 mono track (in Italian), which is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The English-dubbed version features a LPCM 2.0 mono track (in English) with optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The audio track on the Italian cut is very bassy, but dialogue is clear throughout. Subtitles on both versions are clear and easy to read.

Extras

The disc includes an audio commentary by Video Watchdog editor Tim Lucas, on the Italian cut of the film. The disc includes an audio commentary by Video Watchdog editor Tim Lucas, on the Italian cut of the film.

The disc also includes: - an introduction by Alan Jones (3:38). In this introduction, the Italophile critic briefly glances over the film’s history (it was originally planned to be a ‘light romantic thriller’) and suggests the US version is ‘a far more upbeat affair’ than the Italian cut of the film. Jones also foregrounds the film’s status as a progenitor-of-sorts of the later gialli all’italiana, in terms of Bava’s desire to ‘strip [the narrative] down to its thriller essentials’. - a new featurette, ‘All About the Girl’ (21:46). This features interviews with Mikel Koven, author of La Dolce Morte: Italian Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film; Alan Jones; and filmmakers Luigi Cozzi and Richard Stanley, both of whom are admirers of Bava’s work. (All of the participants are interviewed separately.) Cozzi talks about the film’s origins as a romantic comedy which Bava, once he accepted the task of directing the film, turned into a ‘straight’ thriller. The film’s relationship with Hitchcock’s pictures is explored by Koven and Stanley, whilst Jones notes that the picture wasn’t really the first giallo all’italiana, although it was the first to really be labeled as such. The diversity of Bava’s output, something which is often neglected, is discussed by Koven, who also identifies this particular film’s influence over subsequent gialli all’italiana – the ‘foreigner’ protagonist; the focus on the testimoni oculari (eyewitness account); and the amateur sleith. Koven also discusses the film’s use of location shooting, which gives the picture a ‘travelogue quality’. Cozzi draws attention to Bava’s handling of the set-pieces within the film and praises the monochrome photography, stating that ‘his [Bava’s] black and white films are perhaps his most outstanding’; whilst Stanley similarly highlights Bava’s ability to ‘do miraculous things’ with very limited resources. Later Bava films, Cozzi suggests, would have a less defined sense of place – something which Cozzi argues found its way into the films of Dario Argento, which often mix locations in disparate environments in order to develop a deliberately confused sense of geography. Finally, displaying a deliberately provocative sense of hyperbole, Alan Jones offers a very contentious point of view (which seems calculated to cause debate), suggesting – in terms of the dualism between Italian popular cinema and the tradition of ‘art’ cinema – that ‘Nobody wants to sit through the Antonionis or Fellinis anymore’ and, bypassing the work of people like John Alton, putting forward the assertion that Bava was the ‘best’ photographer/director in monochrome. - an interview with John Saxon (9:38). This is the same interview that was included on the US DVD release. - two trailers: the international trailer (2:36) and the US trailer (2:09).

Overall

The Girl Who Knew Too Much is filled with what would soon become the clichés of the thrilling all’italiana: for example, the now all-too-familiar scene in which a ‘real’ detective offers a prohibition in the hopes of warning off the amateur sleuth who is at the centre of the narrative (in this instance, telling Nora, ‘Please don’t start investigating on your own. That’s our job, miss’); travelogue-style footage of Italy; and the hysterical female killer who, when describing her crimes, becomes giddy like a schoolgirl, another overriding trope of the giallo all’italiana (‘You can tell she [the first victim] was a monster. Look at her evil eye’, the killer says here, offering insight into the origins of the film’s original English-language title). There is also some wonderfully macabre imagery: after Ethel expires, in her bed (shot in a way that recalls the imagery of the elderly lady’s corpse in ‘The Drop of Water’, a segment in Bava’s later I tre volti della paura/Black Sabbath, 1963), the bed creaks and squeaks and Ethel’s body moves, startling Nora – until she realises that the movement is caused by nothing more dramatic than Ethel’s cat clawing at the blanket. The Girl Who Knew Too Much is filled with what would soon become the clichés of the thrilling all’italiana: for example, the now all-too-familiar scene in which a ‘real’ detective offers a prohibition in the hopes of warning off the amateur sleuth who is at the centre of the narrative (in this instance, telling Nora, ‘Please don’t start investigating on your own. That’s our job, miss’); travelogue-style footage of Italy; and the hysterical female killer who, when describing her crimes, becomes giddy like a schoolgirl, another overriding trope of the giallo all’italiana (‘You can tell she [the first victim] was a monster. Look at her evil eye’, the killer says here, offering insight into the origins of the film’s original English-language title). There is also some wonderfully macabre imagery: after Ethel expires, in her bed (shot in a way that recalls the imagery of the elderly lady’s corpse in ‘The Drop of Water’, a segment in Bava’s later I tre volti della paura/Black Sabbath, 1963), the bed creaks and squeaks and Ethel’s body moves, startling Nora – until she realises that the movement is caused by nothing more dramatic than Ethel’s cat clawing at the blanket.

The English-dubbed version of the film, under the title The Evil Eye, emphasises the romantic potential within the script (through the addition of Nora’s wistful narration) and has a heavier focus on more overt comedy: in one sequence added to the US cut, when Nora arrives at Aunt Ethel’s house, she undresses in her bedroom and feels eyes upon her; this is represented visually through a framed portrait (of Mario Bava himself, no less) on the wall of the bedroom whose eyes follow Nora around the room, until she covers the portrait with a sheet (‘Oh, no you don’t. You Peeping Tom’, she declares). The shift in tone from this outrageously comic sequence to the macabre death of Ethel is jarring. Meanwhile, one of the strengths of the Italian version of the film is the third person narration, which offers a pastiche of the mode of address associated with the kinds of hard-boiled literary gialli of which Nora is a fan. This works very well within the context of the film. The merits of the English-dubbed version as compared with the Italian edit are open for debate: some commentators prefer the former, whilst others prefer the latter. Having both cuts of the film available in this set, especially considering the previous rarity of the English-dubbed cut on home video, is therefore a big bonus. Packed with fascinating contextual material and graced with the inclusion of the English-dubbed cut of the film, which like the Italian version is given a very strong presentation, Arrow’s Blu-ray release of The Girl Who Knew Too Much offers a superb purchase for Bava fans. References: Bondanella, Peter, 2009: A History of Italian Cinema. London: Continuum International Publishing Hutchings, Peter, 2009: The A to Z of Horror Cinema. Scarecrow Press Koven, Mikel J, 2005: ‘Space and Place in Italian Giallo Cinema: The Ambivalence of Modernity’. In: Everett, Wendy & Goodbody, Axel (eds), 2005: Revisiting Space: Space and Place in European Cinema. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang AG: 115-33 Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Scarecrow Press Mendik, Xavier, 2014: ‘The Return of the Rural Repressed: Italian Horror and the Mezzogiorno Giallo’. In: Benshoff, Harry M (ed), 2014: A Companion to the Horror Film. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons: 390-405 Moliterno, Gino, 2008: Historical Dictionary of Italian Cinema. Scarecrow Press Moliterno, Gino, 2009: The A to Z of Italian Cinema. Scarecrow Press Olney, Ian, 2013: Euro Horror: Classic European Cinema in Contemporary American Culture. Indiana University Press Paul, Louis, 2004: Italian Horror Film Directors. London: McFarland Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland

|

|||||

|