|

|

Hound of the Baskervilles (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st May 2015). |

|

The Film

The Hound of the Baskervilles (Terence Fisher, 1959) The Hound of the Baskervilles (Terence Fisher, 1959)

To some extent, the history of cinema could be said to be the history of Sherlock Holmes adaptations, with Conan Doyle’s ‘consulting detective’ fascinating filmmakers since the dawn of the medium. Writers, directors and actors have found delight in reworking and reinventing the Holmes stories for the big screen and, latterly, for the small screen too: from the thirty second short film Sherlock Holmes Baffled (Arthur Marvin, 1900), through the wartime propaganda of some of Basil Rathbone’s fourteen appearances as Holmes (such as Roy William Neill’s Sherlock Holmes and the Secret Weapon, 1943), beyond the literary faithfulness of Jeremy Brett’s performance as Holmes in John Hawkesworth’s Sherlock Holmes series for Granada Television (1984-94), and on to the modernisation of Conan Doyle’s Holmes stories in Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss’ acclaimed BBC series Sherlock (2010-present). Terence Fisher’s The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959) appeared during the early years of Hammer’s turn towards the production of horror films, with the direction of Fisher and the casting of actors Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee linking the picture with Fisher’s other adaptations for Hammer of classic Gothic texts, The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), Dracula (1958) and The Mummy (1959). Where Fisher’s previous three horror films had been written by Jimmy Sangster, The Hound of the Baskervilles was instead scripted by Peter Bryan (who would go on to write Fisher’s The Brides of Dracula, 1960, and John Gilling’s The Plague of the Zombies, 1966); however, Fisher’s handling of the material, the performances of Cushing and Lee, the production design by Bernard Robinson, Jack Asher’s photography and, of course, James Bernard’s score provide a strong sense of continuity with Fisher’s three prior horror pictures.  Notably, Fisher’s Holmes film was the first in colour and, perhaps surprisingly, was only the third Holmes picture to feature a period setting (Rathbone’s first two Holmes film had been set in Victorian England, but with the third film the series was brought into the then-present day). Cushing’s sensitive performance as Holmes – a character Cushing would also essay for the BBC series Sherlock Holmes (1965-8) – anchors the film, but he is helped immensely by André Morell’s performance as Watson. Where previous film versions of the Holmes stories had sometimes resorted to depicting Watson as something of a buffoon (for example, Nigel Bruce’s performances as Watson in the Basil Rathbone films), Morell played Watson as an intelligent and capable investigator in his own right. Notably, Fisher’s Holmes film was the first in colour and, perhaps surprisingly, was only the third Holmes picture to feature a period setting (Rathbone’s first two Holmes film had been set in Victorian England, but with the third film the series was brought into the then-present day). Cushing’s sensitive performance as Holmes – a character Cushing would also essay for the BBC series Sherlock Holmes (1965-8) – anchors the film, but he is helped immensely by André Morell’s performance as Watson. Where previous film versions of the Holmes stories had sometimes resorted to depicting Watson as something of a buffoon (for example, Nigel Bruce’s performances as Watson in the Basil Rathbone films), Morell played Watson as an intelligent and capable investigator in his own right.

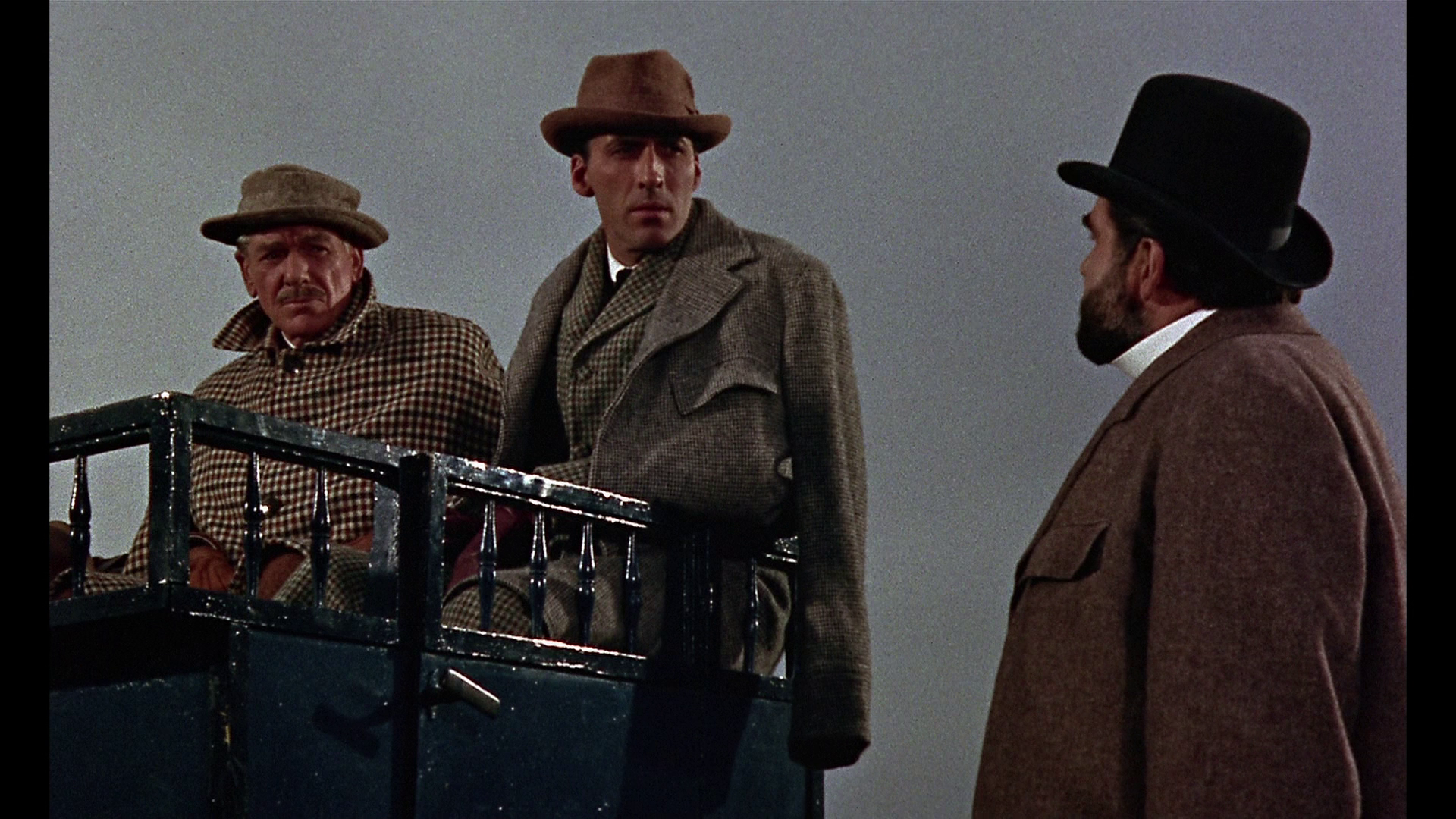

The film begins in the diegetic past, with the murder of a servant girl (Judi Moyens) by the cruel Sir Hugo Baskerville (David Oxley). Fisher reveals this to be a legend being relayed to Holmes and Watson by Doctor Richard Mortimer (Francis De Wolff). One of Sir Hugo’s descendants, Sir Charles Baskerville, has been found dead on the moor, apparently a victim of the curse of the hound of the Baskervilles. Sir Charles Baskerville’s cause of death was heart failure, the man being a victim of a congenital heart problem that afflicts the Baskerville line. Mortimer has approached Holmes to investigate the case and protect Sir Charles Baskerville’s sole heir and nephew, Sir Henry Baskerville (Christopher Lee), who intends to take up residence in Baskerville Hall. Arriving on Dartmoor, Sir Henry Baskerville and Watson discover that an escaped criminal, a murderer named Selden (Michael Mulcaster), is on the loose. Watson also meets the servants of Baskerville Hall, Barrymore (John Le Mesurier) and his wife (Helen Goss), who it is later revealed is also the sister of Selden, the escaped convict. Also introduced are Bishop Frankland (Miles Malleson), a renowned etymologist; and a farmer named Stapleton (Ewen Solon) and his daughter Cecile (Marla Landi). Baskerville Hall, it seems, is haunted by the sobs of a woman, which can be heard at night, and someone seems to be using reflected moonlight to make mysterious signals from the direction of the moor. Joined by Holmes, Watson investigates the apparent plot against the Baskervilles, as Sir Henry begins to fall in love with Cecile. Like Fisher’s previous horror films, The Hound of the Baskervilles focuses on the conflict between the irrational/supernatural and the rational. In this film, as in the novel on which it is based, the ratiocinator Holmes is faced with the legend of the hound of the Baskervilles, a supernatural creature that stalks the moors with the intent of tearing out the throats of the members of the Baskerville family. The curse of the hound which afflicts the Baskerville line is tied to an act of cruelty in the past: Sir Hugo Baskerville’s murder of a servant girl. Barry Forshaw has asserted that ‘[a]s so often in the films that Terence Fisher made for Hammer, the rational and thorough methodology of the Cushing character is presented as the most apposite way to deal with events that defy logical explanation, an effect perhaps reflected in the hard-headed non-intellectual approach of the director’ (Forshaw, 2012: 57).  The film’s opening sequence depicts the cruelty of Sir Hugo, whose presence (or rather, absence) hangs over the film, in much the same way as his portrait dominates the entrance hall of Baskerville Hall. David Oxley portrays Sir Hugo as filled with spite. The film opens with the camera dollying in to a beautiful stained glass window; the shot is accompanied by ominous narration (by Francis de Wolff), which sets the context for the narrative that follows: ‘Know then the legend of the hound of the Baskervilles. Know then that the great hall of the Baskervilles was once held by Sir Hugo of that name, a wild, profane and godless man, an evil man in truth; for there was with him a certain ugly and cruel humour that made his name a byword in the county’. With this, the stained glass window is abruptly, and shockingly, broken by the body of a man being thrown through it. Sir Hugo and his cronies, clad in crimson hunting jackets, gather round the window and sneer through it at their victim, apparently one of Sir Hugo’s servants. ‘Our friend will learn better than to condemn the sport of his masters’, Sir Hugo declares. The other aristocrats mock the servant as Sir Hugo holds him over the flames of the open fireplace in Baskerville Hall: ‘This will teach you to criticise my pleasures’, Baskerville asserts, burning the servant in the fire in an act of pitiless cruelty. The film’s opening sequence depicts the cruelty of Sir Hugo, whose presence (or rather, absence) hangs over the film, in much the same way as his portrait dominates the entrance hall of Baskerville Hall. David Oxley portrays Sir Hugo as filled with spite. The film opens with the camera dollying in to a beautiful stained glass window; the shot is accompanied by ominous narration (by Francis de Wolff), which sets the context for the narrative that follows: ‘Know then the legend of the hound of the Baskervilles. Know then that the great hall of the Baskervilles was once held by Sir Hugo of that name, a wild, profane and godless man, an evil man in truth; for there was with him a certain ugly and cruel humour that made his name a byword in the county’. With this, the stained glass window is abruptly, and shockingly, broken by the body of a man being thrown through it. Sir Hugo and his cronies, clad in crimson hunting jackets, gather round the window and sneer through it at their victim, apparently one of Sir Hugo’s servants. ‘Our friend will learn better than to condemn the sport of his masters’, Sir Hugo declares. The other aristocrats mock the servant as Sir Hugo holds him over the flames of the open fireplace in Baskerville Hall: ‘This will teach you to criticise my pleasures’, Baskerville asserts, burning the servant in the fire in an act of pitiless cruelty.

Sir Hugo then promises to accost the daughter of the servant he has killed for his rowdy audience, presumably with the intention of making her the victim of a rape; but his desire is frustrated when he discovers that she has escaped through an upstairs window. ‘The bitch has got away’, Sir Hugo declares (in a line that Oxley spits with true venom, and which surprisingly wasn’t cut by the BBFC): ‘Set the hounds on her. The hounds! Let loose the pack!’ Sir Hugo and his hunting hounds pursue the girl across the moor, Sir Hugo asserting, ‘May the hounds of hell take me if I can’t hunt her down’. Sir Hugo traps the girl in the ruins of an abbey, stabbing her to death with a ceremonial dagger. However, he is startled by an unnatural howl, and we see from the point-of-view of the titular supernatural hound as it advances on Sir Hugo. As the hound attacks Sir Hugo, the narration returns: ‘And so the curse of Sir Hugo came upon the Baskervilles in the shape of a hound from hell, forever to bring misfortune on the Baskerville family. Therefore take heed and beware the moor in those dark hours when evil is exalted, else you will surely meet the hound of hell, the hound of the Baskervilles. So ends the legend… And what, may I ask, do you think of that, Mr Holmes?’  With the final question, Fisher abruptly reveals that we are in 221B Baker Street, and the opening sequence has been a visualisation of the legend of Sir Hugo and his death at the jaws of the hound, as it is told to Holmes by Doctor Richard Mortimer. As with the opening shot (the sedate dolly in to the stained glass window, which is shockingly shattered as Sir Hugo and his cronies throw the servant through it), Fisher destabilises the audience’s perception: rather than an objective depiction of the story of Sir Hugo Baskerville, he reveals what we have just seen to be a visualisation of the legend, a rare example of potentially unreliable visual narration (much like the famous ‘lying flashback’ in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, 1950). With the final question, Fisher abruptly reveals that we are in 221B Baker Street, and the opening sequence has been a visualisation of the legend of Sir Hugo and his death at the jaws of the hound, as it is told to Holmes by Doctor Richard Mortimer. As with the opening shot (the sedate dolly in to the stained glass window, which is shockingly shattered as Sir Hugo and his cronies throw the servant through it), Fisher destabilises the audience’s perception: rather than an objective depiction of the story of Sir Hugo Baskerville, he reveals what we have just seen to be a visualisation of the legend, a rare example of potentially unreliable visual narration (much like the famous ‘lying flashback’ in Hitchcock’s Stage Fright, 1950).

This opening sequence finds its echo in John Gilling’s The Plague of the Zombies, also written by Peter Bryan. Near the beginning of Gilling’s film is a sequence in which a group of aristocrats involved in a fox hunt tear through the local village, much to the shock of visiting Sir James Forbes (André Morell) and his daughter Sylvia (Diane Clare), with scant regard for a funeral procession, sending the coffin of the man to be interred spilling to the ground, the corpse almost falling out of it. Like Bryan’s script for The Plague of the Zombies, The Hound of the Baskervilles demonstrates a fascination with the relationship between aristocrat and peasant. The actions of the cruel, pitiless aristocrats – intent on torturing and mocking those below them – in the picture’s opening sequence are contrasted with the behaviour of Sir Henry Baskerville who, whilst abrupt in his initial meeting with Holmes (mistaking him for the manager of the London hotel in which he is staying), is well-intentioned. Sir Henry’s first meeting with Cecile involves him pursuing her on horseback, much as Sir Hugo pursued the servant girl in the opening sequence. However, Sir Henry’s growing love for Cecile seems invested with the promise of reconciling the worlds of aristocrat and peasant. Sadly, this becomes complicated in the denouement, which reinforces the chasm that exists between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’.  Holmes’ response to Mortimer’s overview of the legend of Sir Hugo is dismissive: ‘There must be hundreds of similar folk stories’, he declares, ‘I fail to see why I should find this one of singular interest’. Accepting Mortimer’s request that he offer protection to Sir Henry Baskerville and investigate the death of Sir Charles, Holmes nevertheless mocks the superstitious belief in the hound of the Baskervilles. ‘Do you believe that legend?’, Holmes asks Mortimer. ‘There are many things in life and death that we do not understand, Mr Holmes’, Mortimer responds. ‘Then I suggest you might have done better to have consulted a priest instead of a detective’, Holmes suggests dryly. Later, after his first meeting with Sir Henry, Holmes posits that though the legend of the supernatural hound may in his schema be ridiculous, Sir Henry would be wise to heed the legend and avoid the moors at night: ‘The powers of evil can take many forms’, Holmes informs the aristocrat. It’s a warning that rings true as the film builds towards its climax, which reveals the threat to Sir Henry to come from a direction that, to him, is unexpected. Holmes’ response to Mortimer’s overview of the legend of Sir Hugo is dismissive: ‘There must be hundreds of similar folk stories’, he declares, ‘I fail to see why I should find this one of singular interest’. Accepting Mortimer’s request that he offer protection to Sir Henry Baskerville and investigate the death of Sir Charles, Holmes nevertheless mocks the superstitious belief in the hound of the Baskervilles. ‘Do you believe that legend?’, Holmes asks Mortimer. ‘There are many things in life and death that we do not understand, Mr Holmes’, Mortimer responds. ‘Then I suggest you might have done better to have consulted a priest instead of a detective’, Holmes suggests dryly. Later, after his first meeting with Sir Henry, Holmes posits that though the legend of the supernatural hound may in his schema be ridiculous, Sir Henry would be wise to heed the legend and avoid the moors at night: ‘The powers of evil can take many forms’, Holmes informs the aristocrat. It’s a warning that rings true as the film builds towards its climax, which reveals the threat to Sir Henry to come from a direction that, to him, is unexpected.

However, despite Holmes’ pooh-poohing of a supernatural explanation for the death of Sir Charles, and the threat against Sir Henry, during the night Watson seems to experience a vaguely supernatural occurrence during his stay in Baskerville Hall: Watson hears a woman sobbing in one of the rooms (the room from which the servant girl fled Sir Hugo) and, when he investigates, the howls of the hound across the moor. Later in the film, Watson and Sir Henry investigate this phenomenon and, through the window, see a mysterious figure using reflected moonlight to signal to the house. (However, the mysterious sobbing is never fully explained within the narrative.) The threat is compounded when Holmes, after making his appearance to Watson and Sir Henry (having, unbeknownst to the others, quietly investigated the case on the moor), declares that ‘There is more evil around us here than I have ever encountered before’. However, as the film suggests, that evil comes in a human form rather than that of a supernatural hound; it’s no surprise that the hound itself is a product of a theatrical sensibility, being nothing more than a starved dog dressed in a horrifying mask. In contrast with the abrupt denouements of many of Fisher’s films, which although usually featuring the triumph of ‘good’ over ‘evil’, often end with the characters mentally and emotionally scarred by their confrontation with the proverbial abyss, it’s no ‘spoiler’ to anyone even vaguely familiar with the Holmes stories to reveal that The Hound of the Baskervilles ends with Holmes and Watson safe in 221B Baker Street, sharing muffins and tea. In 1959, the BBFC made cuts to the burning of the servant girl’s father in the fire by Sir Hugo; the moment in which Sir Hugo, realising that the servant girl has escaped, sniffs the piece of torn petticoat that she inadvertently leaves just outside the window, muttering ‘insolent cow’; and the finale, in which the titular hound tears at a character’s throat. These cuts seem to have persisted into all home video releases of the film. This release, which is still cut as per the 1959 cinema release, runs for 86:34 mins.

Video

The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation (probably from the same source as the Blu-ray released by Shock in Australia) uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered disc. The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 1.66:1. The 1080p presentation (probably from the same source as the Blu-ray released by Shock in Australia) uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 25Gb of space on a dual-layered disc.

From the outset, there’s a noticeable and marked improvement over the previous DVD releases in terms of colour consistency and detail within this Blu-ray presentation. The increased colour consistency can be seen in the vivid red of the hunting jackets of Sir Hugo and his associates and, later in the film, in the expressionistic green lighting that frames Holmes and Watson as they watch one of the hound’s attacks. Facial close-ups demonstrate an excellent level of detail too. Contrast levels are also very good. Much of the film is dominated by ‘earthy’ tones within the photography and mise-en-scène: browns and autumnal greens are prevalent throughout the picture. The film has a slightly ‘murky’ appearance because of this, and the many night-time sequences are shot with low exposure levels in which the darkness seems to seep into, and envelop, every frame. (This was possibly intended to obscure the fact that most of the film’s exterior sequences were quite clearly shot on a sound studio.) The solid contrast of this Blu-ray presentation ensures that these sequences look more impressive than they ever did on DVD (or, for that matter, VHS). There are a handful of shots that evidence a very minor ‘softness’ to them, which is most likely a characteristic of the original materials. (There is at least one shot in which it seems that the focus puller had a hard time keeping up with the blocking of the actors, which probably seems more noticeable on this HD presentation.) Some very minor wear and tear (flecks and specks) to the source materials is present throughout the film, but nothing too distracting. An excellent encode ensures that the presentation has the natural, organic appearance of 35mm film. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

The disc contains a LPCM 1.0 mono track which is clear throughout and evidences strong range: this can be seen in the sequences which feature the deep growls and snarls of the titular hound, and those that use James Bernard’s score (the music for the opening titles features a deep, bassy brass section and percussion set against shrill, nerve-jangling strings). On that note, it’s worth mentioning that some of Bernard’s score for Dracula works its way into the film, in the sequence in which Sir Hugo chases the servant girl; the use of this piece of music was apparently much to the chagrin of Bernard, who had written a new piece of music for the sequence which appears to have been abandoned by the producers. Optional English subtitles are included.

Extras

The disc contains a rich array of contextual material. The disc contains a rich array of contextual material.

A commentary with film historians Jonathan Rigby and Marcus Hearn features the pair in a non-stop discussion of The Hound of the Baskervilles, discussing its relationship with previous Sherlock Holmes films and its position within both the history of Hammer and the bodies of work of its principal cast and crew. An isolated music and effects track is presented in LPCM 2.0 stereo. ‘Release the Hound!’ (30:20). In this newly-produced documentary, Mark Gatiss and Kim Newman open by discussing the popularity of the Sherlock Holmes character and his continuing importance for film, and examining this picture’s relationship with other Sherlock Holmes and its context within Hammer’s filmography. Also interviewed are the creator of the hound’s mask, Margaret Robinson; the film’s assistant director, Hugh Harlow; and Peter Allchorne, a props chargehand on the film. 'The Many Faces of Sherlock Holmes' (46:04). This 1986 documentary, hosted by Christopher Lee, reflects on the various adaptations of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories and the series’ continuing importance for film and television. 'André Morell: Best of British' (19:43). This featurette, which was also included on the Shock Blu-ray released in Australia, features Morell’s son, Jonathan Rigby, Dennis Meikle and David Miller reflecting on André Morell’s career, focusing on the actor’s work for Hammer. 'Actor's Notebook: Christopher Lee' (12:59). In this archival interview, Christopher Lee discusses his experiences during the production of The Hound of the Baskervilles. 'Hound of the Baskervilles' excerpts: 'Mr Sherlock Holmes' (14:36); 'The Hound of the Baskervilles' (6:24). These feature Christopher Lee reading passages from Conan Doyle’s novel. Finally, the disc also includes the film’s trailer (1:59) and a stills gallery (2:24).

Overall

Fisher’s The Hound of the Baskervilles is a superb film, filled with wonderful bits of business: the repetition of Holmes, the world’s most famous consulting detective, being mistaken for a manager of a hotel (by Sir Henry Baskerville) and, later, the man who has been commissioned with the task of repairing Bishop Frankland’s telescope, is highly amusing and points to the theatricality of Cushing’s Holmes – who cleverly adapts how he speaks in order to manipulate other characters into responding in the way in which, in order to solve the case, he needs them to. (Towards the climax, Holmes spitefully tells Sir Henry, who is preparing for a dinner with the Stapletons, ‘You’d better be off. You mustn’t be late for your peasant friends [….] I should have thought in your new position, you would have cultivated worthier friends. I hope you enjoy their rabbit pie’. Holmes tells Watson that he was being ‘purposefully rude’ so that Sir Henry would leave Baskerville Hall on his own.) Fisher’s The Hound of the Baskervilles is a superb film, filled with wonderful bits of business: the repetition of Holmes, the world’s most famous consulting detective, being mistaken for a manager of a hotel (by Sir Henry Baskerville) and, later, the man who has been commissioned with the task of repairing Bishop Frankland’s telescope, is highly amusing and points to the theatricality of Cushing’s Holmes – who cleverly adapts how he speaks in order to manipulate other characters into responding in the way in which, in order to solve the case, he needs them to. (Towards the climax, Holmes spitefully tells Sir Henry, who is preparing for a dinner with the Stapletons, ‘You’d better be off. You mustn’t be late for your peasant friends [….] I should have thought in your new position, you would have cultivated worthier friends. I hope you enjoy their rabbit pie’. Holmes tells Watson that he was being ‘purposefully rude’ so that Sir Henry would leave Baskerville Hall on his own.)

The film deviates from Conan Doyle’s novel in a number of ways, which led to criticisms at the time of its release that it took liberties with its source material. However, as Paul Leggett has suggested, ‘[i]n reality Fisher and Hammer hadn’t done anything different in adapting The Hound of the Baskervilles than they had done with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or Bram Stoker’s Dracula [….] The difference this time was that more people had probably read The Hound of the Baskervilles […] Hence the criticism of “changing the story” was raised more frequently’ (Leggett, 2002: 83). It’s a shame that Hammer didn’t continue making Sherlock Holmes films, as despite its original mixed reception The Hound of the Baskervilles is arguably the equal of Fisher’s previous three horror pictures (The Curse of Frankenstein, Dracula and The Mummy) which established Hammer as a studio associated with the production of horror films. This presentation of The Hound of the Baskervilles is very good, easily eclipsing the various DVD releases, and the disc contains a superb array of contextual material, especially given the barebones nature of previous home video releases of the film. Fans of Terence Fisher’s work for Hammer will find this an essential purchase. References: Forshaw, Barry, 2012: British Crime Film: Subverting the Social Order. London: Palgrave Macmillan Leggett, Paul, 2002: Terence Fisher: Horror, Myth and Religion. North Carolina: McFarland & Company

|

|||||

|