|

|

Society (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (7th June 2015). |

|

The Film

Society (Brian Yuzna, 1989) Society (Brian Yuzna, 1989)

Brian Yuzna’s name is indelibly linked with the 1980s boom in ‘body horror’ pictures, largely thanks to his work as a producer on Stuart Gordon’s Re-animator (1985), a film whose ‘defiance of all norms and desire to put the ravaged body at the centre of the horror experience make it an important example of body horror’ (Reyes, 2014: 68). Body horror, as a subgenre, is loosely defined but in Body Gothic: Corporeal Transgression in Contemporary Literature and Film, Xavier Reyes asserts that the ‘general understanding seems to be that, if a text generates fear from abnormal states of corporeality, or from an attack upon the body, we might find ourselves in front of an instance of body horror’ (ibid.: 52). In The A to Z of Horror Cinema, Peter Hutchings defines body horror as ‘a type of horror film that first emerged during the 1970s’ and which contains ‘graphic and sometimes clinical representations of human bodies that were in some way out of the conscious control of their owners’ (Hutchings, 2008: 41). The films, such as David Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977), are essentially about ‘the ultimate alienation—alienation from one’s own body—but this has often been coupled with a fascination with the possibility of new identities that might emerge from this’ (ibid.). A leitmotif within these films is the depiction of the human body in a state of transformation (ibid.). In their focus on themes of alienation, body horror films are often inherently political; and the bodies-in-transformation, or bodies-in-decay, within these films are sometimes interpreted as metaphors for the body politic. Clive Barker, an author and filmmaker often associated with the body horror subgenre thanks to his novels and films such as Hellraiser (1987), published within his anthology The Books of Blood a short story entitled ‘The Body Politic’, in which a man discovers his own hands rebelling against his will – part of a wider revolt of hands against the individuals to whom they are attached. The story, Xavier Reyes suggests, uses ‘limbic mutiny’ as a metaphor for ‘the disruptive potential of corporeal rebellion’ (Reyes, op cit.). Society (1989), Yuzna’s directorial debut, is an outrageously and openly political horror film. In a 2006 interview, Yuzna asserted that ‘As a former hippie, the idea of politics as being not only important but entertaining and inextricably linked to art was a part of my mentality’ (Yuzna, quoted in Towlson, 2014: 188). Yuzna’s anti-authoritarian, satirical approach had already been evidenced in the films he produced for Stuart Gordon to direct, Re-animator and From Beyond (1986). Re-animator was the first in a number of films associated with Yuzna to depict ‘authority as depraved and corrupt’: Towlson suggests that in Yuzna’s pictures as both director and producer, ‘patriarchal authority in all its forms is open to question, whether it be the military (Return of the Living Dead 3), men’s control of women’s bodies (Bride of Re-animator, Initiation, Progeny), or masculinity itself (The Dentist, The Dentist 2)’ (ibid.). The films ‘also display a developed class-consciousness colored by 1960s radicalism’ in which Yuzna seems to ‘see capitalist society as a hidden oligarchy in which the majority of wealth is kept by a small minority of rich families while the poor are exploited and “fed upon”’ (ibid.).  Jon Towlson groups Society with John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) and Bob Balaban’s Parents (1989): Towlson suggest these films of the late-1980s ‘portray[ed] America’s fashionable, wealthy and influential elite as a race of aliens or monstrous parasites that leech off the lower classes while keeping their alien nature hidden’ (Towlson, op cit.: 190). Towlson argues that these films are underpinned by the concept of false consciousness: ‘that people are unable to see things—exploitation, oppression and social relations—as they really are because their world view is imposed upon them by the ruling classes’ (ibid.). Throughout the narrative of Society, the film’s protagonist Billy ‘becomes politically aware’ and ‘begins to see the true nature of privilege, and fights against it’ (ibid.). For Annalee Newitz, despite Society’s playful, ironic approach to its material, the film’s ‘message is unmistakeable: the rich are repulsive alien monsters’ (Newitz, 2006: 3). They are also ‘literally incestuous’, leading to the inexorable suggestion that ‘wealth is being hoarded by a few inbred elites who have no intention of sharing it with anybody who isn’t part of their “family”’ (ibid.). Jon Towlson groups Society with John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) and Bob Balaban’s Parents (1989): Towlson suggest these films of the late-1980s ‘portray[ed] America’s fashionable, wealthy and influential elite as a race of aliens or monstrous parasites that leech off the lower classes while keeping their alien nature hidden’ (Towlson, op cit.: 190). Towlson argues that these films are underpinned by the concept of false consciousness: ‘that people are unable to see things—exploitation, oppression and social relations—as they really are because their world view is imposed upon them by the ruling classes’ (ibid.). Throughout the narrative of Society, the film’s protagonist Billy ‘becomes politically aware’ and ‘begins to see the true nature of privilege, and fights against it’ (ibid.). For Annalee Newitz, despite Society’s playful, ironic approach to its material, the film’s ‘message is unmistakeable: the rich are repulsive alien monsters’ (Newitz, 2006: 3). They are also ‘literally incestuous’, leading to the inexorable suggestion that ‘wealth is being hoarded by a few inbred elites who have no intention of sharing it with anybody who isn’t part of their “family”’ (ibid.).

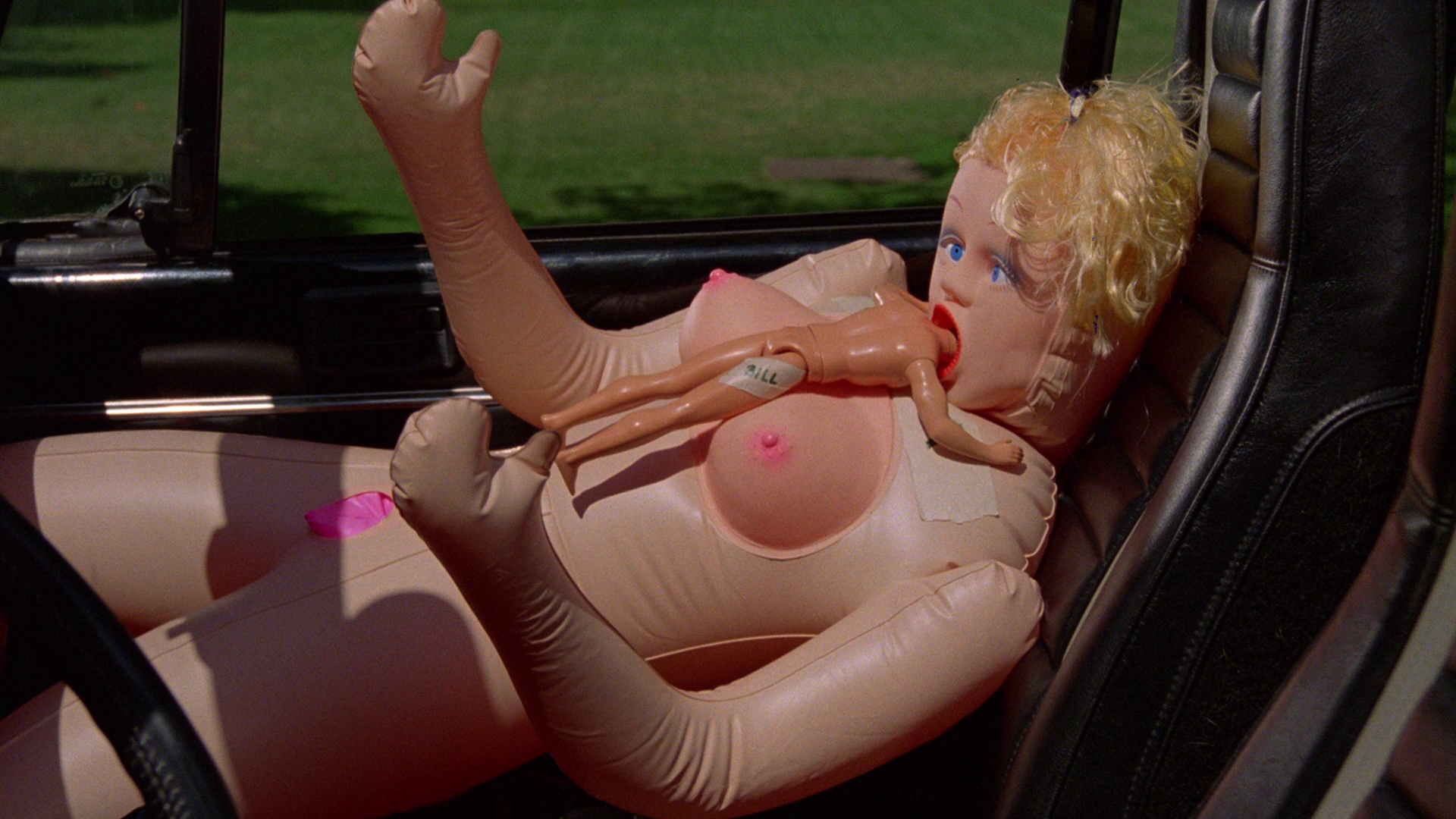

Yuzna has suggested that ‘One of the reasons the upper class fail is because the gene pool gets too limited [….] They need to spike the breed with the lower classes which is the same way they breed dogs, spike the breed with a mongrel’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.: 190). This idea formed the premise for Society. The film focuses on Bill Whitney (Billy Warlock), a young man who despite enjoying the trappings of wealth (a huge home in Beverly Hills, a Jeep) feels alienated from his family, including his parents (Charles Lucia and Connie Danese) and sister Jenny (Patrice Jennings), who is preparing for her ‘coming out’ party whilst Bill’s parents also make preparations for an important party at their home which is to be attended by Judge Carter (David Wiley). Bill also makes regular visits to a psychiatrist, Dr Cleveland (Ben Slack), for what appears to be an anxiety-related issue. Bill’s life becomes more complicated when Jenny’s former boyfriend David Blanchard (Tim Bartell) breaks into the Whitney house, apparently with the intention of warning Jenny about something. ‘Something very weird is going on here’, Blanchard warns Jenny and Bill, who refuse to listen and eject him from the house. (Later, Blanchard’s words echo with Bill when Bill enters Jenny’s room to borrow her suncream and sees his sister in the shower; although the view is slightly obscured by the frosted glass of the shower cubicle, it appears that Jenny’s upper torso is facing in the wrong direction as she washes her back.) Jenny is now involved in a relationship with popular up-and-comer Ted Ferguson (Ben Meyerson), part of the Beverly Hills ‘in crowd’, and claims that Blanchard is stalking her. Bill’s girlfriend Shauna (Heidi Kozak) pesters Bill to get an invited into the party Ferguson is throwing, but when Bill confronts Ferguson on the beach, Ferguson ridicules and bullies Bill. Shortly after, Bill encounters Blanchard, who claims he has important news. He plays for Bill an audio recording made during Jenny’s ‘coming out’ party, which Bill missed owing to an alternate engagement, and which appears to contain evidence of Bill’s family engaging in acts of incest and possibly also murder: ‘First we dine’, Bill’s father says to Jenny on the tape, ‘then copulation. First, with someone your own age, then your mother and me’. Bill listens as the recording appears to document Jenny having sex with Ted in the presence of her parents, followed by dreadful screams. Bill takes the audio tape to Cleveland. However, Cleveland switches it, replacing it with another, far less sinister recording in which Bill’s parents and Jenny discuss how excited she is about her ‘coming out’. Shortly after, Blanchard is killed in a car wreck, and Bill begins to suspect that Blanchard’s death is no accident and is instead part of a cover-up. Returning home, Bill is disgusted to find his family uninterested in Blanchard’s death and more focused on the upcoming party that the Fergusons are throwing. ‘So, what are you gonna wear?’, Jenny asks. ‘To the funeral?’, Bill responds. ‘No, you weirdo’, Jenny laughs, ‘to the Fergusons’ party’.  Meanwhile, much to the chagrin of Shauna, Bill begins to fall under the spell of mysterious, seductive brunette Clarisa (Devin DeVasquez), despite being told that she is ‘bad news’. After encountering Clarisa at the Fergusons’ party, Bill returns home with her and the couple have sex. Afterwards, Bill sees Clarisa on the bed, her body momentarily contorted impossibly. ‘What’s the matter, Billy?’, Clarisa asks. ‘You… you were in a funny position’, Bill responds, unable to fully articulate what he believes he has seen. Meanwhile, much to the chagrin of Shauna, Bill begins to fall under the spell of mysterious, seductive brunette Clarisa (Devin DeVasquez), despite being told that she is ‘bad news’. After encountering Clarisa at the Fergusons’ party, Bill returns home with her and the couple have sex. Afterwards, Bill sees Clarisa on the bed, her body momentarily contorted impossibly. ‘What’s the matter, Billy?’, Clarisa asks. ‘You… you were in a funny position’, Bill responds, unable to fully articulate what he believes he has seen.

Bill confronts his parents and also tries to reveal the nature of what he believes to be a conspiracy involving his parents and Judge Carter to his peers at school. However, he is ridiculed. At home, he is confronted by his parents and Cleveland, who sedates Bill and has him transported to hospital in an ambulance. Milo follows the ambulance and, investigating, is told that Bill is dead. However, Bill is still alive and being held, sedated, in a private room under an assumed name. After he awakens, he witnesses a vision played out in silhouette on the curtains that surround his bed: an attack on Blanchard. However, this is a delusion and Bill exits the hospital, delirious. He and Milo return to the Whitney house, just in time for Judge Carter’s party, where the true nature of the conspiracy is revealed: it’s an event in which the rich literally feed off the poor (‘Didn’t you know, Billy Boy? The rich have always sucked off low class shit like you’, Ted declares during this sequence). The film begins with a woman’s voice gently humming the Eton Boating Song and a shot of the Whitneys’ lavish house at nighttime. Inside the darkened house, a visibly anxious Bill wanders through the rooms as bizarre, mocking laughter can be heard on the audio track. The home is enshrouded in darkness and shot with wide-angle lenses, as if to emphasise its cavernous nature. Bill takes a knife from the kitchen, apparently with the desire to protect himself from an unknown assailant. In the hallway he seems to prepare to be attacked, but he is stopped by his family, who turn on the lights: it appears that Bill is suffering one of his recurring anxiety attacks. With this brief opening sequence, Yuzna establishes Society’s focus on the theme of alienation from the home and the family unit, and the depiction of the family home as an unfamiliar, threatening and nightmarish space. The latter is a trait which Society shares in common with Wes Craven’s horror films of the same period, including A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) and The People Under the Stairs (1991), which also depicts the (metaphoric and deeply symbolic) domestic space as labyrinthine and under threat both from within and without.  From here, Yuzna cuts to one of the many conversations between Bill and his psychiatrist that punctuate the narrative at fairly regular interviews. ‘It’s like a nightmare’, Bill asserts. ‘Last night?’, Dr Cleveland asks. ‘My life’, Bill tells him, ‘I get scared. My parents, my sister, you’. ‘Why?’, Cleveland queries. ‘I feel like something’s gonna happen’, Bill says, ‘and if I scratch the surface there’ll be something terrible underneath’. With this, Bill bites into an apple and looks at it, his face betraying his disgust as Yuzna cuts to a close-up of the apple, worms writhing within it and spilling out of it. In many ways this opening sequence calls to mind the opening moments of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and its depiction of small-town America, with its white picket fences and happy citizens, before the camera takes us below the neatly-cut lawns to reveal the bugs beneath, the soundtrack dominated by the amplified sounds of their buzzing and crunching. Both Yuzna and Lynch reveal, in the opening sequences of their respective films, the worms hiding in the proverbial apple. From here, Yuzna cuts to one of the many conversations between Bill and his psychiatrist that punctuate the narrative at fairly regular interviews. ‘It’s like a nightmare’, Bill asserts. ‘Last night?’, Dr Cleveland asks. ‘My life’, Bill tells him, ‘I get scared. My parents, my sister, you’. ‘Why?’, Cleveland queries. ‘I feel like something’s gonna happen’, Bill says, ‘and if I scratch the surface there’ll be something terrible underneath’. With this, Bill bites into an apple and looks at it, his face betraying his disgust as Yuzna cuts to a close-up of the apple, worms writhing within it and spilling out of it. In many ways this opening sequence calls to mind the opening moments of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and its depiction of small-town America, with its white picket fences and happy citizens, before the camera takes us below the neatly-cut lawns to reveal the bugs beneath, the soundtrack dominated by the amplified sounds of their buzzing and crunching. Both Yuzna and Lynch reveal, in the opening sequences of their respective films, the worms hiding in the proverbial apple.

After Dr Cleveland tries to persuade Bill that his anxiety is ‘perfectly normal’ for his age and that ‘it will pass, I assure you’, the film’s opening titles play out over vaguely-defined, almost surreal images of bodies, blood and slime. The composition (a jumble of disembodied limbs laid on top of one another) is in some ways reminiscent of Francois Géricault’s series of anatomical paintings of body parts from the Paris Morgue, preparation for ‘The Raft of the Medusa’: Paul Koudounaris, author of The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses, has described Géricault’s anatomical studies of corpses and body parts as being dominated by ‘the morbid tones of putrefying flesh against a warm chiaroscuro which fades into a dark background and seems timeless and quiet, giving these anatomical fragments a presence that is almost iconic’ (Koudounaris, quoted in Ebenstein, 2012: np). The same words could be used to describe the opening titles sequence of Society. On the soundtrack a lone female voice (belonging to soprano Helen Moore) sings to the tune of the Eton Boating Song: ‘(Verse 1) When you get tired of winning / And you get tired of fame / Or when your head is spinning / And you’ve drunk all the best champagne / (Chorus) Then we’ll all sing together / To society we’ll be true / Then we’ll all sing together / Society waits for you / (Verse 2) Oh, how the rich get richer / Playing the rolling game / Only the poor get poorer / We feed off them all the same’.  After the opening titles, we see Billy playing basketball with his friend Milo (Evan Richards). Billy beats Milo, telling him jokingly, ‘Matter of good breeding, Milo’. ‘Yeah, you’re Mr Perfect’, Milo quips, ‘You’ll probably end up assassinating the president’. Billy’s words will be repeated to him later, in a much more threatening context, by the members of the ruling elite. At Judge Carter’s party, Bill’s father tells him, ‘Jesus, Bill, you never were one of us’. To this, Cleveland adds, ‘You almost don’t understand, do you, Bill? You’re a different race from us, a different species, a different class. You’re not one of us. You have to be born into society’. ‘Alien scum’, Bill asserts. ‘No, we’re not from outer space or anything like that’, Cleveland assures Bill, ‘We have been here as long as you have. It’s a matter of good breeding, really’. Similar foreshadowing is also evident within the carefully-constructed mise-en-scène: Jenny’s bedroom contains a bizarre, contorted statuette (a human figure on its haunches, its legs in the air and its head between them, and its feet impossibly facing in the wrong direction) which stands on her dresser. After the opening titles, we see Billy playing basketball with his friend Milo (Evan Richards). Billy beats Milo, telling him jokingly, ‘Matter of good breeding, Milo’. ‘Yeah, you’re Mr Perfect’, Milo quips, ‘You’ll probably end up assassinating the president’. Billy’s words will be repeated to him later, in a much more threatening context, by the members of the ruling elite. At Judge Carter’s party, Bill’s father tells him, ‘Jesus, Bill, you never were one of us’. To this, Cleveland adds, ‘You almost don’t understand, do you, Bill? You’re a different race from us, a different species, a different class. You’re not one of us. You have to be born into society’. ‘Alien scum’, Bill asserts. ‘No, we’re not from outer space or anything like that’, Cleveland assures Bill, ‘We have been here as long as you have. It’s a matter of good breeding, really’. Similar foreshadowing is also evident within the carefully-constructed mise-en-scène: Jenny’s bedroom contains a bizarre, contorted statuette (a human figure on its haunches, its legs in the air and its head between them, and its feet impossibly facing in the wrong direction) which stands on her dresser.

The meetings with Dr Cleveland that appear throughout the film function almost as a form of narration, allowing Bill to express his feelings of alienation. ‘We’re just one big happy family, except for a little incest and psychosis’, Bill tells Cleveland, informing the psychiatrist that ‘They [his family] don’t approve of me, okay? They don’t accept my friends. They don’t talk to me like they do Jenny. Hell, they don’t even look like me’. During the session, Bill comes to the conclusion that ‘I think I was adopted’. Cleveland tries to assuage Bill’s fears, telling him (in words whose depth of irony will only be revealed towards the end of the film), ‘you know, you really deserve what’s gonna happen to you’. ‘What’s gonna happen?’, Bill asks. ‘You’re gonna make a wonderful contribution to society’, Cleveland informs him. This phrase, rather than the promise of fulfilled potential, seems more like a threat, and it is repeated later in the film when, after investigating Blanchard’s death, Bill has a conversation with his mother, who tells him, ‘You know, you’ll make such a great contribution to society. You’ll do our whole family proud’. The precise nature of this ‘contribution’ is kept ambiguous until the sequence depicting the party thrown for Judge Carter. These meetings with Dr Cleveland also suggest that, as the narrative progresses and the conspiracy becomes more prominent within it, Bill’s guiding point-of-view may be unreliable: that Bill, who has hinted at psychosis within one of his earliest meetings with Cleveland, may simply be paranoid. At first, Bill’s fears seem to be evidence of a generalised anxiety (‘I don’t know why I’m afraid, but I…’, Bill tells Cleveland after first hearing Blanchard’s recording of Jenny’s ‘coming out’ party) but as the film’s narrative progresses, these fears become much more specific. At this point in the film, though we are shown sequences taking place outside the point-of-view of Bill (for example, Cleveland meeting with the Whitneys and Judge Carter after Bill leaves, and the Whitneys alone with Carter), the precise nature of the enigma remains a mystery until the final third of the film. Meanwhile, Blanchard is shocked at the extent to which Bill’s existence has been blinkered to the true nature of his family’s behaviour: ‘What, you’ve been living with these people all your life and you didn’t know anything about this?’, a gobsmacked Blanchard asks Bill after playing the audio recording for him. Bill’s conscious awareness of what his family have been doing, it seems, has been obscured by the easy materialism of his life (the large, luxurious home; Jenny’s closet filled with expensive clothes; Bill’s Jeep) and the work of his therapist, Cleveland.  When Cleveland swaps the tape, this is done in an attempt to further pull the veil over Bill’s eyes, confirming for Bill that his feelings are simply a paranoid fantasy. Cleveland lectures Bill and prescribes medication (a sedative?) for him: ‘Billy, people are what they are’, Cleveland declares (though at this point in the narrative, the irony of this statement is already readily apparent to the viewer who shares Bill’s paranoid sentiments), ‘Now you have to learn to accept that, and you have to learn to accept society’s rules of privacy. If you don’t follow the rules, Billy, bad things happen. Now some people make the rules and some people follow the rules. It’s a matter of what you’re born to’. However, after Cleveland drugs Bill and has him held in the hospital, Bill escapes with an awareness that his paranoia is well-founded. ‘Come on, can’t you see they’re setting you up for something?’, Milo asks the delirious Bill after Bill escapes from the hospital. ‘Paranoid?’, Bill laughs, ‘I’m not paranoid: all my fears are real’. When Cleveland swaps the tape, this is done in an attempt to further pull the veil over Bill’s eyes, confirming for Bill that his feelings are simply a paranoid fantasy. Cleveland lectures Bill and prescribes medication (a sedative?) for him: ‘Billy, people are what they are’, Cleveland declares (though at this point in the narrative, the irony of this statement is already readily apparent to the viewer who shares Bill’s paranoid sentiments), ‘Now you have to learn to accept that, and you have to learn to accept society’s rules of privacy. If you don’t follow the rules, Billy, bad things happen. Now some people make the rules and some people follow the rules. It’s a matter of what you’re born to’. However, after Cleveland drugs Bill and has him held in the hospital, Bill escapes with an awareness that his paranoia is well-founded. ‘Come on, can’t you see they’re setting you up for something?’, Milo asks the delirious Bill after Bill escapes from the hospital. ‘Paranoid?’, Bill laughs, ‘I’m not paranoid: all my fears are real’.

Yuzna was inspired to direct Society following a number of projects as a producer which collapsed owing to tensions between different producers (for example, a proposed adaptation of H P Lovecraft’s story ‘The Shadow Over Innsmouth’, which eventually evolved into Stuart Gordon’s Dagon, 2001) or directors who pulled out at the last minute (Yuzna, cited in Fischer, 2000: 660). One of these was a film that was to be titled The Men, and which focused on ‘an idea [Dan O’Bannon, who was to direct] had at the time about a woman who discovers all men are aliens’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). However, Dan O’Bannon pulled out of the project at the last minute, something which Yuzna believes was down to O’Bannon’s manager not being happy with the deal for O’Bannon to direct (ibid.). Disheartened by the failure of The Men to enter production, Yuzna decided to direct his next film himself, and elements of the paranoid premise of The Men would find their way into Society.  ‘It’s [wishing to direct is] a natural thing to do if you work with movies anyway’, Yuzna has asserted, and with Society and Bride of Re-Animator (1989) he learned the craft of film directing (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). However, Yuzna admits that at this stage in his career, he paid more attention to ideas than to the construction of the films’ narratives, stating in interview that ‘I always put try to put much more in the stories than they can support because I’m an idea person’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.: 661). Partly, Yuzna suggest, this is owing to the fact that Yuzna came relatively late to the film world: ‘I had been a carpenter and an artist and when I was 35 I decided to make movies whereas Stuart [Gordon] had been working on staging and story and direction’ and therefore had more institutional support and grounding in issues of narrative (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). Structurally, Yuzna’s films are linked by ‘a strong element of the carnivalesque’ which explodes in a finale that takes the form of ‘big, transgressive, crazy, orgiastic type scenes’ (Yuzna, quoted in Towler, op cit.: 189). Yuzna has claimed that these sequences of excess are in some way shaped by his viewings, as a child, of Hollywood epics such as The Ten Commandments (Cecil B DeMille, 1956) and Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) (Yuzna, cited in ibid.). Society conforms to this template, with the final sequence depicting Judge Carter’s ‘shunting’ party taking up around a third of the film’s running time and featuring some outrageous special effects work from Japanese special effects artist Screaming Mad George. Screaming Mad George’s work, featuring the melding, fragmentation and erosion of the human body, tips the film’s climax into the realm of the carnivalesque. ‘It’s [wishing to direct is] a natural thing to do if you work with movies anyway’, Yuzna has asserted, and with Society and Bride of Re-Animator (1989) he learned the craft of film directing (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). However, Yuzna admits that at this stage in his career, he paid more attention to ideas than to the construction of the films’ narratives, stating in interview that ‘I always put try to put much more in the stories than they can support because I’m an idea person’ (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.: 661). Partly, Yuzna suggest, this is owing to the fact that Yuzna came relatively late to the film world: ‘I had been a carpenter and an artist and when I was 35 I decided to make movies whereas Stuart [Gordon] had been working on staging and story and direction’ and therefore had more institutional support and grounding in issues of narrative (Yuzna, quoted in ibid.). Structurally, Yuzna’s films are linked by ‘a strong element of the carnivalesque’ which explodes in a finale that takes the form of ‘big, transgressive, crazy, orgiastic type scenes’ (Yuzna, quoted in Towler, op cit.: 189). Yuzna has claimed that these sequences of excess are in some way shaped by his viewings, as a child, of Hollywood epics such as The Ten Commandments (Cecil B DeMille, 1956) and Ben-Hur (William Wyler, 1959) (Yuzna, cited in ibid.). Society conforms to this template, with the final sequence depicting Judge Carter’s ‘shunting’ party taking up around a third of the film’s running time and featuring some outrageous special effects work from Japanese special effects artist Screaming Mad George. Screaming Mad George’s work, featuring the melding, fragmentation and erosion of the human body, tips the film’s climax into the realm of the carnivalesque.

Society was released in cinemas in the UK, whereas in the US the film went straight to video before finding a limited theatrical release in American cinemas in 1992. Yuzna suggested this was owing to the ways in which the issue of social class, and the reality of divisions between social classes, is perceived in Britain and America: ‘I realized that the British don’t have a hard time realizing that there are social classes. In America, it’s like messing with their mythology; you’re threatening their whole world. The American world view is predicated on this idea that those who have more really deserve it…. One of the points of Society is that not only do a very small number of people control the world, but… whatever class you are born in is the class you will grow up in’ (Yuzna, quoted in Newitz, op cit.: 3-4). Certainly, the film was more warmly received in Europe than in America, and surprisingly the then-notoriously strict BBFC passed the film uncut for both cinema and home video release, perhaps seeing beyond the outrageous effects work to the genuinely satirical heart of the film. (Equally surprisingly, during the mid-1990s the BBC screened an uncut version of the film as part of its long-running Moviedrome series.) The US release was cut for an ‘R’ rating, though aside from a few trims to the ‘shunting’ sequences at the end of the film, most of footage cut from the US ‘R’ rated version was narrative material relating to the development of Bill and Clarisa’s relationship. (For more precise detail about the cuts to the US ‘R’ rated version of the film, please see this link.) This release contains the uncut version of the film, with a running time of 99:16 mins.

Video

The film, on this Blu-ray release, is presented in the 1.78:1 aspect ratio, which seems to be near-as-dammit to the film's intended aspect ratio. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up approximately 27Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc.  Very good contrast is evidenced from the opening sequence depicting Billy’s nightmarish night-time prowl through his home, and continues to be prevalent throughout the film. The image is richly-textured, with a very good level of detail and a depth missing in the film’s prior DVD releases. There are some very minor flecks and specks of debris that can be seen from time to time, but they are barely noticeable. The colour palette is rich and deep, especially in the vivid reds of the scenes during the ‘shunting’ party but evident elsewhere in, for example, the bold sky blue walls of the Whitneys’ home; the heat of the Californian sunshine emanates from the screen. Very good contrast is evidenced from the opening sequence depicting Billy’s nightmarish night-time prowl through his home, and continues to be prevalent throughout the film. The image is richly-textured, with a very good level of detail and a depth missing in the film’s prior DVD releases. There are some very minor flecks and specks of debris that can be seen from time to time, but they are barely noticeable. The colour palette is rich and deep, especially in the vivid reds of the scenes during the ‘shunting’ party but evident elsewhere in, for example, the bold sky blue walls of the Whitneys’ home; the heat of the Californian sunshine emanates from the screen.

The presentation is based on the same source, a new 2k restoration of the film conducted by TLE Films, as the German Blu-ray release from Capelight, issued in 2013. However, Arrow’s new Blu-ray release, though smaller in file size than the Capelight disc (27Gb compared to the Capelight release’s 33Gb) seems to have a stronger encode which results in a more natural grain structure (evident in the large screen grabs at the bottom of this review, but more noticeable in motion). A visual comparison of this release with the German Blu-ray release from Capelight is contained at the very bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a lossless LPCM 2.0 stereo track. This is a rich audio track, demonstrating good range: the soundscape is clear and deep, though the film’s audio mix is not showy by any means. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc contains a very strong array of contextual material, including:  An audio commentary with director Brian Yuzna. Moderated by David Gregory, this is a new commentary, different to the one which appeared on the film’s DVD release from Anchor Bay (and was transplanted onto the German Blu-ray release). It’s an engaging track to listen to: Yuzna is a fiercely intelligent but profoundly modest filmmaker with a fascinating grasp of the contexts within which his films can be situated but without the need to demonstrate this in an overt, patronising manner. An audio commentary with director Brian Yuzna. Moderated by David Gregory, this is a new commentary, different to the one which appeared on the film’s DVD release from Anchor Bay (and was transplanted onto the German Blu-ray release). It’s an engaging track to listen to: Yuzna is a fiercely intelligent but profoundly modest filmmaker with a fascinating grasp of the contexts within which his films can be situated but without the need to demonstrate this in an overt, patronising manner.

Also included are a number of featurettes: - ‘Governor of the Society’ (16:51) features Brian Yuzna discussing the film. Yuzna reflects on his first experiences in Hollywood, admitting that ‘I really didn’t know what the different jobs were’ but realising through his work as a producer on films like Re-animator and Stuart Gordon’s Dolls (1987) that ‘the director got all the credit’. Inspired by this, and also by the disappointment of finding financing for a number of films but discovering that the directors were unable to follow these projects into production, Yuzna decided to enter in the world of film direction. He brokered a deal with Wild Side for two films, Society and Bride of Re-animator; knowing that as a sequel to Stuart Gordon’s cult hit, Bride of Re-animator was an almost certain success, he thus safeguarded his first film as a director, Society. Yuzna admits that Society was to some extent shaped by The Men, the abandoned Dan O’Bannon project, and when approached with the script for Society Yuzna was drawn to it because it ‘had the same paranoia The Men had’. Consequently, Yuzna took ‘the energy I had [gathered] for The Men [and] pushed it into Society’. The ‘shunting’ within the film, not present in the original script (which was simply about ‘a blood cult’) was shaped by the nightmares Yuzna experienced after watching Michael Curtiz’s Doctor X (1932) as a child, and also by Yuzna’s love of surrealism. Yuzna also suggests that the film offers a Baudrillardian focus on the concept of simulacra, highlighting ‘the place between sanity and insanity, between dream and nightmare, or between life and dream’. Yuzna admits that he pays little regard to narrative structure or to Hollywood conventions of plotting, declaring that ‘I always say, inspiration first. The logic can always come after’. Yuzna also talks about the film’s distribution and how the European response was very positive whilst US audiences were slightly bewildered by the picture because the film ‘doesn’t fit a regular category’. - Masters of the Hunt’ (22:22). This featurette includes interviews with Billy Warlock, Devin DeVasquez, Ben Meyerson and Tim Bartell. Interviewed separately, the participants talk about their work prior to Society and how they were approached to appear in the film. Yuzna’s approach to directing is examined, with Tim Bartell saying that Yuzna and some of the other members of the crew ‘were a little afraid of frightening actors’ and thus shied away from foregrounding the more bizarre elements of the script. Billy Warlock suggests that Yuzna is an extremely methodical director: ‘Brian knew exactly what he was doing’, Warlock says, ‘Everything was mapped out, set up’ and done ‘by the book’. Warlock and DeVasquez discuss the difficulties they faced in playing their characters’ growing relationship and, in particular, filming the sex scene that takes place between Bill and Clarisa – something which was new to both of them. All of the participants reflect on the ‘shunting’ sequence and Screaming Mad George’s work on the picture, with Meyerson saying that ‘It’s literally like horror porn: it’s [Screaming Mad George’s imagery is] so sexual. The response to the film is also discussed, with Warlock expressing his shock at the positive reception the film received in the UK, as compared with how audiences responded to it in America. Ultimately, Tim Bartell says, ‘as timely as it [Society] was in the Reagan era, in certain ways it’s more timely now. - ‘Champion of the Shunt’ (20:39). In this featurette, Screaming Mad George, and technicians David Grasso and Nick Benson comment on their makeup effects for the film. Brian Yuzna Q&A (38:34), recorded at the Celluloid Screams Festival in Sheffield in 2014. Yuzna engages with the film’s social context and reflects on the film’s development and reception. The film’s original trailer (2:07). Screaming Mad George music video (6:08). Retail versions of Society, in special digipack packaging, also include a booklet and a comic book sequel to the film.

Overall

Ultimately, Society is a satirical assault on Reagan’s America and a number of its key institutions, including the nuclear family. James Marriott has argued that in its satirical approach to the concept of entitlement and the idea that ‘those who have more really deserve it’, Society ‘is the necessary inverse to American celebrations of elitist mediocrity like Beverly Hills 90210 and Baywatch’ (Marriott, 2012: np). Offering an almost Situationist-style example of détournment, for some of its running time the film adopts, with savage irony, the mise-en-scène of such contemporaneous celebrations of the lives of the young and wealthy as Beverly Hills 90210 and, at first subtly but later not so subtly, undercuts this with a growing sense of horror and the carnivalesque. The film is often grouped with films such as Carpenter’s They Live, in terms of its depiction of the ruling elite as, quite literally, an alien race who maintain their position of power within the status quo through the production of a false consciousness. However, Society might also be compared with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, in terms of the suggestion that beneath the veneer of wealthy, happy, productive suburbia exists a profound, cannibalistic darkness. Like Lynch’s film, Society is also structured as a subversive coming-of-age story, with Billy’s transition into young adulthood accompanied by an increasing political awareness. In fact, Kenneth MacKinnon has suggested that Society is ‘the American mainstream horror version’ of Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1988), in the sense that both pictures ‘deal with the amorality of the rich and powerful, or rather of those whom wealth automatically makes powerful in nations which, as Greenaway puts it, know the price of everything but the value of nothing’ (MacKinnon, 1992: 199). Ultimately, Society is a satirical assault on Reagan’s America and a number of its key institutions, including the nuclear family. James Marriott has argued that in its satirical approach to the concept of entitlement and the idea that ‘those who have more really deserve it’, Society ‘is the necessary inverse to American celebrations of elitist mediocrity like Beverly Hills 90210 and Baywatch’ (Marriott, 2012: np). Offering an almost Situationist-style example of détournment, for some of its running time the film adopts, with savage irony, the mise-en-scène of such contemporaneous celebrations of the lives of the young and wealthy as Beverly Hills 90210 and, at first subtly but later not so subtly, undercuts this with a growing sense of horror and the carnivalesque. The film is often grouped with films such as Carpenter’s They Live, in terms of its depiction of the ruling elite as, quite literally, an alien race who maintain their position of power within the status quo through the production of a false consciousness. However, Society might also be compared with David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, in terms of the suggestion that beneath the veneer of wealthy, happy, productive suburbia exists a profound, cannibalistic darkness. Like Lynch’s film, Society is also structured as a subversive coming-of-age story, with Billy’s transition into young adulthood accompanied by an increasing political awareness. In fact, Kenneth MacKinnon has suggested that Society is ‘the American mainstream horror version’ of Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1988), in the sense that both pictures ‘deal with the amorality of the rich and powerful, or rather of those whom wealth automatically makes powerful in nations which, as Greenaway puts it, know the price of everything but the value of nothing’ (MacKinnon, 1992: 199).

An absolutely superb film with a strong cult following, Society finally finds the release it deserves in this Blu-ray from Arrow. The film’s fans will probably want to hold on to the Anchor Bay DVD (or the German Capelight Blu-ray) for the old commentary with Yuzna, but the first class presentation of the main feature and the wealth of well-produced and insightful contextual material on this Blu-ray release from Arrow makes it an essential purchase. References: Fischer, Dennis, 2000: Science Fiction Directors, 1895-1998. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc Hutchings, Peter, 2008: The A to Z of Horror Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Ebenstein, Joanna, 2012: ‘Théodore Géricault's Morgue-Based Preparatory Paintings for "Raft of the Medusa," A Guest Post by Paul Koudounaris’. [Online.] http://morbidanatomy.blogspot.co.uk/2012/02/theodore-gericaults-morgue-based.html MacKinnon, Kenneth, 1992: The Politics of Popular Representation: Reagan, Thatcher, AIDS, and the Movies. London: Associated University Presses Marriott, James, 2012: Virgin Film Series: Horror Films. London: Random House Newitz, Annalee, 2006: Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture. Duke University Press Reyes, Xavier Aldana, 2014: Body Gothic: Corporeal Transgression in Contemporary Literature and Film. University of Wales Press Towlson, Jon, 2014: Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages from ‘Frankenstein’ to the Present. North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc Visual comparison with the German Blu-ray released by Capelight in 2013. Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

Capelight BD:

Arrow BD:

More grabs from the Arrow Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|