|

|

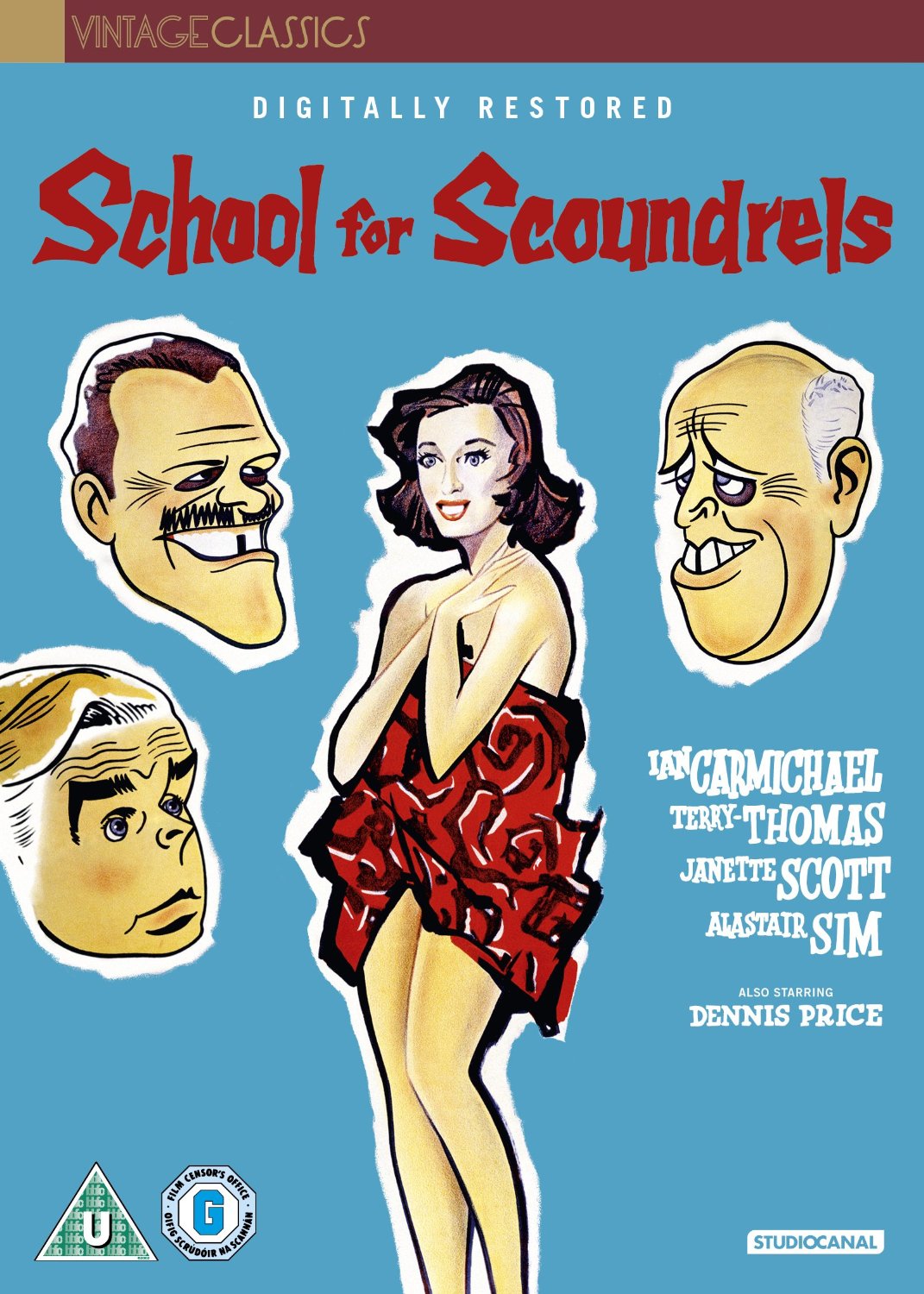

School for Scoundrels

R2 - United Kingdom - Studio Canal Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th October 2015). |

|

The Film

School for Scoundrels (Robert Hamer, 1960) School for Scoundrels (Robert Hamer, 1960)

Based on Stephen Potter’s series of bestsellers Oneupmanship, Gamesmanship and Lifemanship, Robert Hamer’s School for Scoundrels (1960) offers a mischeviously funny satirical look at the self-serving, materialistic Britain that had emerged during the post-war economic boom of the 1950s. School for Scoundrels began production not long after the completion of I’m All Right Jack (John Boulting, 1959), which severed star Ian Carmichael’s five picture contract with the Boulting brothers. School for Scoundrels was produced by an American producer, Hal E Chester, and marked the final film directed by Robert Hamer. The script was written by Peter Ustinov. Reputedly, at least according to both Ian Carmichael and his co-star Janette Scott, director Hamer was at this point in his life suffering from ‘a really bad drink problem’ (Scott, quoted in Fairclough, 2011: np). Ultimately, this resulted in Hamer being removed from the shoot in the final few weeks of production and being replaced as director with an uncredited Cyril Frankel (Ian Carmichael, in ibid.). In addition to this, during production of School for Scoundrels Chester apparently struggled to produce the financing required to complete the picture and ended up remortgaging his house (Scott, in ibid.). As a consequence, Chester sought to make the script more palatable for an American audience and hired Patricia Moyes, better known as a writer of mystery novels, to rework Ustinov’s script. Apparently, none of Moyes’ work was used in the finished film, although both she and Chester are credited for writing the script rather than Ustinov. Carmichael later reflected that ‘Hal did not write a single perishing line! All he did was grumble about Peter [Ustinov] and bring in American gags for the American market’ (Carmichael, quoted in ibid.). On the other hand, some of the gags in the script were reputedly doctored on the set by blacklisted American screenwriter Frank Tarloff, who like Ustinov was uncredited in the finished film and underpaid for his contribution (Buhle & Wagner, 2015: 175-6).  The film opens with Henry Palfrey (Ian Carmichael) arriving by train in Yeovil, where he makes his way to the College of Lifemanship. There, Palfrey approaches the founder of the institution, Potter (Alistair Sim), who explains his philosophy of ‘oneupmanship’: that life is predicated on getting ‘one up’ on one’s rivals. Via an extended flashback, it is revealed that Palfrey has fallen in love with a young woman, April Smith (Janette Scott). However, Palfrey has a rival for April’s affections: sleazy bounder Ray Delauney (Terry-Thomas). After accidentally encountering April and Palfrey in a restaurant, Delauney steals April away from Palfrey with the lure of his flashy car, his easy knowledge of food and wine, and his apparently superior skills at tennis – with which he thrashes Palfrey during a ‘friendly’ match at the local country club. In addition, inspired by Delauney’s ownership of a flashy sportscar, Palfrey visits a car dealership owned by the shady Dunstan (Dennis Price) and Dudley (Peter Jones), who sell Palfrey an old banger for the ridiculously high sum of seven hundred pounds by telling him that the vehicle was once the property of a maharajah. (The car, Delauney later declares, ‘looks like a Polish stomach pump’.) The film opens with Henry Palfrey (Ian Carmichael) arriving by train in Yeovil, where he makes his way to the College of Lifemanship. There, Palfrey approaches the founder of the institution, Potter (Alistair Sim), who explains his philosophy of ‘oneupmanship’: that life is predicated on getting ‘one up’ on one’s rivals. Via an extended flashback, it is revealed that Palfrey has fallen in love with a young woman, April Smith (Janette Scott). However, Palfrey has a rival for April’s affections: sleazy bounder Ray Delauney (Terry-Thomas). After accidentally encountering April and Palfrey in a restaurant, Delauney steals April away from Palfrey with the lure of his flashy car, his easy knowledge of food and wine, and his apparently superior skills at tennis – with which he thrashes Palfrey during a ‘friendly’ match at the local country club. In addition, inspired by Delauney’s ownership of a flashy sportscar, Palfrey visits a car dealership owned by the shady Dunstan (Dennis Price) and Dudley (Peter Jones), who sell Palfrey an old banger for the ridiculously high sum of seven hundred pounds by telling him that the vehicle was once the property of a maharajah. (The car, Delauney later declares, ‘looks like a Polish stomach pump’.)

Palfrey, it seems, has enrolled at the College of Lifemanship in order to learn how to get ‘one up’ over Delauney and the others – such as Dunstan, Dudley and even Palfrey’s employee Gloatbridge (Edward Chapman) – who have subjected him to humiliation. At Potter’s school, Palfrey passes through classes in partymanship (where the students are taught how to ‘dominate’ a party scenario), gamesmanship (in which the students are taught how to get ‘one up’ in any competitive game) and woo-manship. In the latter class, Palfrey is told to ensure that any glass given to his female partner must be slippery enough that she spill her drink on her dress – thus giving Palfrey the opportunity to persuade her to remove her dress and replace it with his dressing gown. This strategy, Potter says, ‘places you very definitely “one up”, or perhaps more, depending on how much of a gentleman you are’.  Palfrey continues his education in lifemanship ‘in the field’, as it were. With a disguised Potter in tow, Palfrey visits Dunstan and Dudley’s car dealership and tells them a tall tale which results in the two salesmen happily allowing him to return the car they previously sold him – which they exchange for a new, functioning vehicle and, on top of this, one hundred pounds. Palfrey then arranges a repeat tennis match with Delauney; and during this match, Palfrey uses the skills he gained in his gamesmanship classes to get ‘one up’ on Delauney, thus humiliating his rival in front of April. For this achievement, following the departure of Delauney Potter awards Palfrey with his ‘Certificate of Lifemanship’. Palfrey continues his education in lifemanship ‘in the field’, as it were. With a disguised Potter in tow, Palfrey visits Dunstan and Dudley’s car dealership and tells them a tall tale which results in the two salesmen happily allowing him to return the car they previously sold him – which they exchange for a new, functioning vehicle and, on top of this, one hundred pounds. Palfrey then arranges a repeat tennis match with Delauney; and during this match, Palfrey uses the skills he gained in his gamesmanship classes to get ‘one up’ on Delauney, thus humiliating his rival in front of April. For this achievement, following the departure of Delauney Potter awards Palfrey with his ‘Certificate of Lifemanship’.

In his biography of Alistair Sim, Mark Simpson suggests that School for Scoundrels and The Happiest Days of Your Life (Frank Launder, 1950) ‘bookend’ the 1950s: where the latter film ‘marked the beginning of a decade of quintessential British humour – during which time a woman’s reputation would be ruined if she were caught in a single man’s bedroom – School for Scoundrels brought that decade to a close’ (Simpson, 2008: 160). Arriving at the College of Lifemanship, Palfrey witnesses Potter explaining his philosophy of one-upmanship to the students. Potter argues that the distinction between male and female is ‘a mere superficial division of minor importance’. There is, he claims, ‘another division, another dichotomy, more profound’. This division is between ‘winners and losers. Top men and underdogs. In a word, the one-up and the one-down’. Potter’s philosophy of lifemanship ‘is the science of being one-up on your opponents at all times. It is the art of making him feel that somewhere, somehow, he has become less than you. Less desirable, less worthy, less blessed’. Your opponents, Potter tells the students, are ‘everybody, in a word, who is not you’. (In its delicious irony and its satirical approach to what our American cousins referred to as the ‘“Me” generation’, Potter’s line anticipates Andrew Wyke’s admonishment of Milo Tindle in Anthony Shaffer’s play Sleuth because Tindle is ‘a not-one-of-me’.) ‘And the purpose of your life’, Potter asserts, ‘must be to be one-up on them – because, and mark this well, he who is not one-up is one-down’.  With this monologue, the film establishes its undercurrent of dark humour, a predominantly bleak examination of a society which is predicated on pushing others to one side or exploiting them in order to achieve one’s goals. The film, Robert Fairclough has argued in his biography of Ian Carmichael, is ‘a movie where there were no good guys’ (Fairclough, op cit.). The object of Palfrey’s affections, April is a fickle woman, seduced by Delauney’s material wealth, his confidence and – it seems – his politely cruel streak; and, with the aim of winning April’s affections, Palfrey seeks to emulate the worst aspects of Delauney’s character by enrolling in the College of Lifemanship. Bounders, it seems, win – at least when it comes to the game of love. And love is a phenomenon that isn’t spared from Potter’s cynical worldview: when Palfrey asks Potter, ‘What if she [April] doesn’t like me?’, Potter responds by reminding his student that ‘that’s a small detail. Some of the most successful marriages are made up of people who scarcely talk to each other’. With this monologue, the film establishes its undercurrent of dark humour, a predominantly bleak examination of a society which is predicated on pushing others to one side or exploiting them in order to achieve one’s goals. The film, Robert Fairclough has argued in his biography of Ian Carmichael, is ‘a movie where there were no good guys’ (Fairclough, op cit.). The object of Palfrey’s affections, April is a fickle woman, seduced by Delauney’s material wealth, his confidence and – it seems – his politely cruel streak; and, with the aim of winning April’s affections, Palfrey seeks to emulate the worst aspects of Delauney’s character by enrolling in the College of Lifemanship. Bounders, it seems, win – at least when it comes to the game of love. And love is a phenomenon that isn’t spared from Potter’s cynical worldview: when Palfrey asks Potter, ‘What if she [April] doesn’t like me?’, Potter responds by reminding his student that ‘that’s a small detail. Some of the most successful marriages are made up of people who scarcely talk to each other’.

As Fairclough suggests, in School for Scoundrels ‘all the main characters are self-serving; the honest, if put-upon, Palfrey becomes as predatory as Delauney in order literally to seduce a superficial girl who is dazzled by fast cars, charm and wealth’ (Fairclough, op cit.). Following his successful acquisition of the principles of one-upmanship in the classroom environment, Palfrey is set free and the second half of the film offers a dark mirror of the first half. Where in the first half of the film, Palfrey is sold a duff car by the two salesmen Dunstan and Dudley, in the second half of the picture Palfrey visits the two salesmen and spins them a yarn (with the help of some in-the-field mentorship by Potter) which results in him exchanging the car for both a much better model and a hundred guineas. In the first half of the picture, Palfrey is beaten at tennis by Delauney and humiliated in front of April; but in the second half of the film, Palfrey arranges a repeat match and, using his wits rather than a natural ability at the game, thrashes and humiliates Delauney. The film ends with Palfrey applying the lessons he learned in his woo-manship classes to maneuver April out of her clothing and into his dressing gown (by ensuring her drinking glass is slippery, thus resulting in her spilling her drink over her dress), and finally into his bedroom (by staging a knock at the door which would he convinces April would result in her embarrassment) – where he feigns a lack of sexual interest in her (referring to her as ‘sexless’) in order to provoke her desire to prove him wrong. An angry Delauney is, in the closing scene, shown following Palfrey’s steps to the College of Lifemanship. The system of exploitation is, it seems, a self-perpetuating cycle: in a system of one-upmanship, there will always be students for Potter’s school. The film is uncut and runs for 90:58 mins (PAL).

Video

School for Scoundrels is presented in the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, with anamorphic enhancement. The monochrome photography fares very well on this DVD presentation, which is from a clean source and evidences good, nicely-balanced contrast – with mid-tones which are strong and defined.

Audio

Audio is presented via a Dolby Digital 2.0 mono track, which is clean and clear throughout. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included, and these are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc contains several interviews with: - Peter Bradshaw (13:37). Here, the film critic for The Guardian discusses School for Scoundrels and reflects on what has given the film such an enduring appeal. Bradshaw argues that part of the film’s appeal is its use of the satirical ‘instructional’ formula of Stephen Potter’s books. The comedy within the film ‘is all about class’, Bradshaw suggests, and the desire from the middle classes to push […] up’. The film was ‘made at a time when the class system is in flux’, with Palfrey representing the ‘aspirational middle-class chap’ – like Jim Dixon in Kingsley Amis’ Lucky Jim (1954). However, Palfrey encounters a ‘glass ceiling’ and a ‘new arena of class conflict’: tennis clubs, golf clubs, restaurants, places where ‘a sneer or a raised eyebrow can put you in your place’. The crux of Palfrey’s humiliation, Bradshaw argues, is the restaurant scene in which Palfrey is first grateful towards Delauney for securing both he and Alice a table and then experiences the dishonour of being ‘squashed’ under a ‘social juggernaut’. - Chris Potter (11:44), the grandson of author Stephen Potter on whose books School for Scoundrels was based. Potter reflects on his grandfather’s love of games, which was to some extent the origin of his series of books – along with a sense of storytelling that he refined whilst working for the BBC. Potter also discusses his grandfather’s approach to writing his books and his intention to produce ‘a little bit of social satire’. The origins of what became the tennis scene in School for Scoundrels (rooted in the novel Gamesmanship), Potter reveals, grew out of a real event in Stephen Potter’s life. Potter also talks about the production of the film and the perception by the original producers, who intended to make the film in America and cast Cary Grant, that the ‘humour was too English’. This led to Hal Chester being offered the option of producing the picture, and Potter discusses Ustinov’s uncredited contribution as the film’s scriptwriter (the car salesmen Dunstan and Dudley were based on characters in Ustinov’s radio programme) and Robert Hamer’s drinking problem and resultant expulsion from the production. - Graham McCann on Terry-Thomas (11:00). In this interview, the author of Bounder!, the biography of Terry-Thomas, discusses the actor’s background and the trajectory of his career. The disc also includes: - a stills gallery. - the film’s original trailer (2:27).

Overall

School for Scoundrels is a delight. A satirical look at the ‘me first’ ethos and a sly comment on British culture’s obsession with social class and class difference, the film is arguably as relevant today as when it was made. It’s also a deceptively dark film, in terms of its depiction of human nature: in order to compete for the affections of the fickle, materialistic April, Palfrey seeks to ape the behaviour of the sneering Delauney. As Pond suggests in his monologue to the students of his school, the system of one-upmanship is self-perpetuating and leads to an escalation of exploitation and inequality. School for Scoundrels is a delight. A satirical look at the ‘me first’ ethos and a sly comment on British culture’s obsession with social class and class difference, the film is arguably as relevant today as when it was made. It’s also a deceptively dark film, in terms of its depiction of human nature: in order to compete for the affections of the fickle, materialistic April, Palfrey seeks to ape the behaviour of the sneering Delauney. As Pond suggests in his monologue to the students of his school, the system of one-upmanship is self-perpetuating and leads to an escalation of exploitation and inequality.

The presentation of the film on this DVD release is very good, and the disc also contains some pleasing contextual material. References: Buhle, Paul & Wagner, Dave, 2015: Hide in Plain Sight: The Hollywood Blacklistees in Film and Television, 1950-2002. London: Macmillan Fairclough, Robert, 2011: This Charming Man: The Life of Ian Carmichael. London: Aurum Press Simpson, Mark, 2008: Alistair Sim: The Star of ‘Scrooge’ and ‘The Belles of St Trinian’s’. Gloucestershire: The History Press

|

|||||

|