|

The Film

River’s Edge (Tim Hunter, 1986) River’s Edge (Tim Hunter, 1986)

The film begins with Tim (Joshua Miller), a 12 year old boy, throwing his sister’s doll into the river. Tim spots Samson (Daniel Roebuck), a local teenager whose surname (Tollet) has led his friends to nickname him ‘John’ (Tollet=Toilet=John), on the riverbank, whooping and hollering. John is sitting next to the naked corpse of a girl; the girl is Jamie (Danyi Deats), one of John’s schoolfriends.

Tim is the younger brother of Matt (Keanu Reeves), another of John’s friends. Matt and John are also friends with Layne (Crispin Glover) and Clarissa (Ione Skye). Matt and Layne travel to the home of a local pot-dealer and misfit, the middle-aged Feck (Dennis Hopper). Feck is a former biker who lost a leg in a motorcycle accident and claims to have murdered a young woman almost twenty years ago. Feck also claims to have been in hiding from the police ever since. He lives alone, with only a blow-up sex doll, Ellie, for company.

At school, John reveals to his classmates that he has murdered Jamie. At first, the others laugh it off, but John takes Layne and Matt to the spot where Jamie’s body lies. Layne sees it as his mission to protect John from being arrested for the crime. Word soon spreads about the murder, and more and more members of the local school travel out to see the corpse, the incident apparently offering a transitory moment of excitement in their dull lives. (‘A bunch of us are going there to check it [the corpse] out’, one student declares excitedly.)

When, unbeknownst to the others, Matt informs the police about the body, Layne and John return to John’s house to find the police outside. Layne takes John to Feck’s place, with the intention that John should be able to hide there for a few days. When Tim realises that his brother Matt has called the police, he reacts angrily: ‘You dirty traitor’, Tim tells Matt, ‘You’re gonna pay for what you did. You’re gonna die for what you did’. Tim visits his nunchaku-wielding pre-teen friend, and together they decide to raid Feck’s place and steal Feck’s gun – with the intention of using the revolver to kill Matt.

Upon its release, Vincent Canby referred to River’s Edge as ‘the year’s most riveting, most frightening horror film’, suggesting that the affectless high school children depicted within the film are as much ‘undead’ as a screen monster such as Count Dracula (Canby, quoted in Caputi, 1991: 62). Alluding to Canby’s analysis of the film, Jane Caputi has asserted that as much as in George A Romero’s zombie picture Night of the Living Dead (1968), River’s Edge is haunted by ‘an image of the unburied dead’: Jamie’s naked corpse, which ‘the camera insistently returns to’, using ‘that cold body’ as a metaphor for ‘psychic death in life’, with ‘the gang of aimless, unfeeling, and anomic teenagers who—either through hyperkineticism [in the case of Layne] or generalized dullness—truly embody the emotional state of the undead’ (ibid.). The film, Caputi suggests, may be best understood ‘as a filmic exploration of the emotional borders of the “Numbed State,” one inhabited by those who manifest the paradigmatic consciousness […] of […] the nuclear age’ (ibid.). Upon its release, Vincent Canby referred to River’s Edge as ‘the year’s most riveting, most frightening horror film’, suggesting that the affectless high school children depicted within the film are as much ‘undead’ as a screen monster such as Count Dracula (Canby, quoted in Caputi, 1991: 62). Alluding to Canby’s analysis of the film, Jane Caputi has asserted that as much as in George A Romero’s zombie picture Night of the Living Dead (1968), River’s Edge is haunted by ‘an image of the unburied dead’: Jamie’s naked corpse, which ‘the camera insistently returns to’, using ‘that cold body’ as a metaphor for ‘psychic death in life’, with ‘the gang of aimless, unfeeling, and anomic teenagers who—either through hyperkineticism [in the case of Layne] or generalized dullness—truly embody the emotional state of the undead’ (ibid.). The film, Caputi suggests, may be best understood ‘as a filmic exploration of the emotional borders of the “Numbed State,” one inhabited by those who manifest the paradigmatic consciousness […] of […] the nuclear age’ (ibid.).

The film’s title itself (‘River’s Edge’) references the idea of a liminal space – a threshold or a point of in-betweenness – which is explored throughout the narrative: the liminal space between the land and the water, on which John kills Jamie and where her body rests; the liminal space between childhood and adulthood in which the majority of the film’s characters exist; the liminal space between life and death, which in the film is represented by Jamie’s unburied body, her wide open – but deathly blank – staring eyes seemingly imploring her peers who view her body, and by extension the film’s audience itself. (Near identical iconography of a dead girl haunts David Lynch’s thematically similar television series Twin Peaks, 1990-1, of which Tim Hunter directed several episodes; but where Jamie’s corpse is naked and her eyes are wide open, Laura Palmer is famously ‘wrapped in plastic’ and her eyes are closed, suggesting that she is asleep or at rest.) Riverbanks have historically often been spaces associated with rituals (and the characters in this film could be said to undergo a ‘right of passage’ in their encounter with death), and have also been associated with sites of power or wealth – ironic, inasmuch as the community depicted within the film is one which is dominated by poverty and ‘deadendness’.

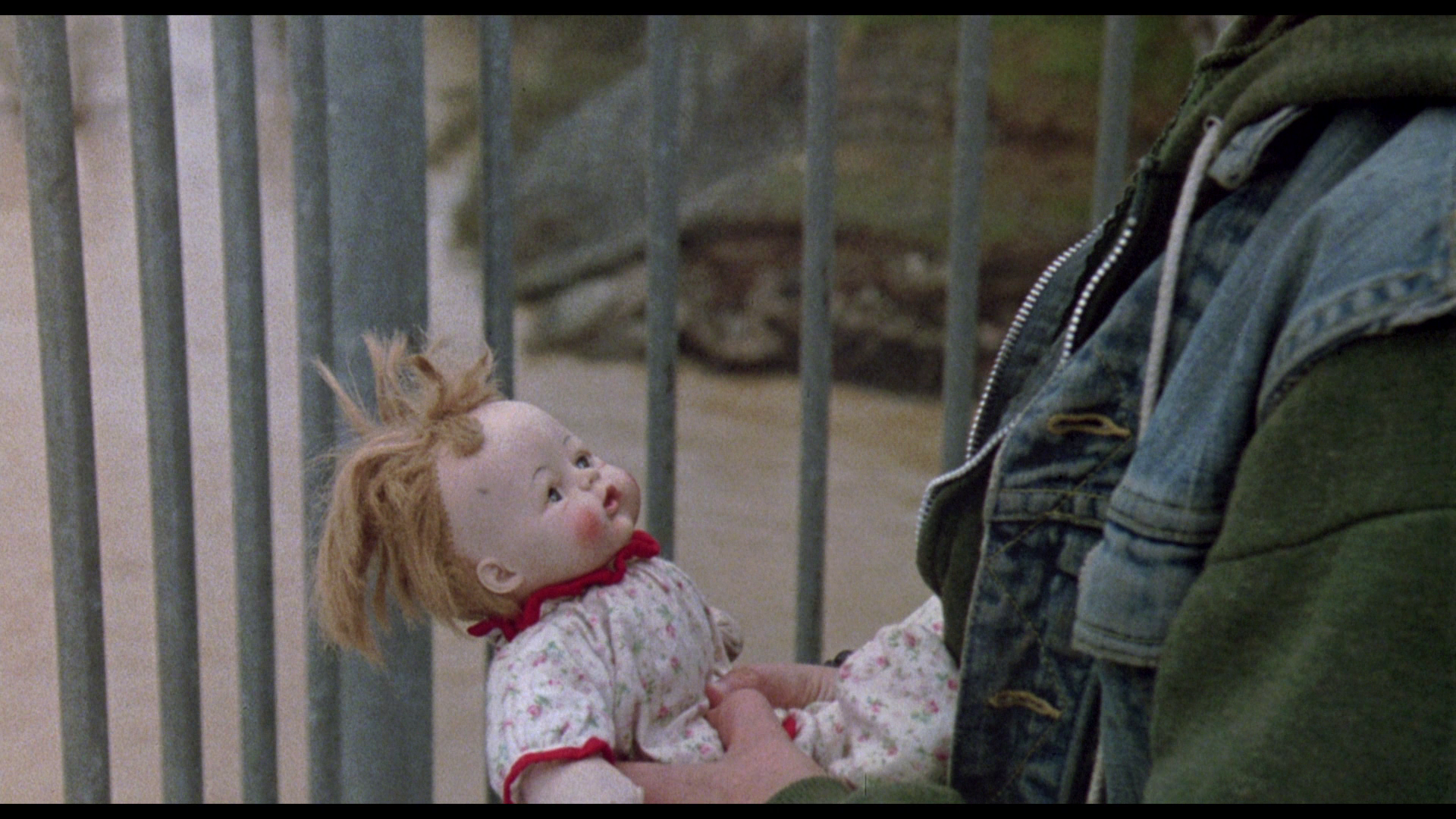

The film begins with an image of this liminal space: the river itself, in grainy monochrome footage reminiscent of the are, bure, boke (‘rough, blurry, out of focus’) style of Japanese photography popularised by the likes of Daido Moryama. It’s a composite image: the area at the top of the frame, the land beyond the river, is frozen – complete with frozen film grain – whilst the river below continually flows and churns. This monochrome image (clearly post-processed into monochrome) gradually segues into a colour shot with the same compositional elements – though in colour the dirty brown shade of the water is apparent. The camera slowly pans away from the river to the railings – symbolic of confinement and entrapment – of the bridge over the river on which the camera is positioned, and then tracks down to Tim holding his sister’s doll, which he thrusts through the railings and, shortly afterwards, throws into the dirty water below. Tim, a young boy of twelve who wears an insolent expression and a dandy-esque earring, looks down at the doll before throwing it; and the doll looks up at him with the same imploring but dead eyes as Jamie. A subsequent shot shows the dirty water of the river churning below. Tim puts the doll through the railings and drops it into the filthy water, watching it being carried away by the current. The film begins with an image of this liminal space: the river itself, in grainy monochrome footage reminiscent of the are, bure, boke (‘rough, blurry, out of focus’) style of Japanese photography popularised by the likes of Daido Moryama. It’s a composite image: the area at the top of the frame, the land beyond the river, is frozen – complete with frozen film grain – whilst the river below continually flows and churns. This monochrome image (clearly post-processed into monochrome) gradually segues into a colour shot with the same compositional elements – though in colour the dirty brown shade of the water is apparent. The camera slowly pans away from the river to the railings – symbolic of confinement and entrapment – of the bridge over the river on which the camera is positioned, and then tracks down to Tim holding his sister’s doll, which he thrusts through the railings and, shortly afterwards, throws into the dirty water below. Tim, a young boy of twelve who wears an insolent expression and a dandy-esque earring, looks down at the doll before throwing it; and the doll looks up at him with the same imploring but dead eyes as Jamie. A subsequent shot shows the dirty water of the river churning below. Tim puts the doll through the railings and drops it into the filthy water, watching it being carried away by the current.

Tim hears someone shouting. He moves to the other side of the bridge on which he stands. He sees, and sharing his perspective the film’s audience see via a long shot, a young man – later revealed to be John – sitting on the bank of the river. John is shouting and whooping. He sits next to the dead girl, Jamie, though her body is indistinct in the long shot and only revealed to use when we cut from the long shot of John to a medium shot of the same, which then pans away from John to reveal Jamie’s naked corpse; Jamie’s eyes are turned towards the camera, staring imploringly – like those of the doll. With this series of shots, the doll (which belongs to Tim’s sister) is metonymically connected to Jamie’s corpse, and Tim’s heartless treatment of the doll is metonymically connected to John’s murder of Jamie. Returning home, Tim spitefully tells his little sister Kim, in reference to her beloved dolly Missy, ‘I killed her. I drowned her’. Tim’s revelation is mirrored shortly afterward, in another scene, when John reveals to his schoolfriends that he murdered Jamie; in response to this, John’s friends laugh off John’s claim as absurd (‘What’d you do, man, sit on her?’; ‘Crazy fucking story like that, why should anyone believe you?’). In response to Tim’s revelation that he ‘drowned’ Missy, Matt admonishes him, in words that could apply equally to John: ‘Stupid enough to pull a stunt like that, but then to go and brag about it’. Much later in the picture, Matt catches Tim and begins to rain blows on him. ‘Why do you pull shit like that?’, Matt asks, ‘Answer me! Why? Why?’ The suggestion, perhaps, is that Matt is sublimating his confusion about John’s crime onto his brother – once again equating John’s murder of Jamie with Tim’s cruel disposal of his sister’s precious doll.

In the film, the sense of liminality – being between childhood and adulthood – often manifests itself in a state of confusion or uncertainty. The young people in the film are unsure how to respond to John’s initial assertion that he has killed Jamie, taking this initially as a joke. They are even more unsure of how to respond to the sight of her corpse. When John takes Layne and Matt to where Jamie’s body is, Layne declares excitedly, ‘This is unreal, completely unreal’. Both Layne and Matt are blasé about their encounter with Jamie’s corpse, at least for the time being. Soon, however, Layne comes to see himself as the person who needs to rally the proverbial troops in order to protect John from being arrested for the killing. Layne references the myths of Hollywood films, suggesting that John’s crime offers a chance for Layne to step outside his mundane, dead-end existence: ‘It’s like some fucking movie, you know’, Layne says after seeing Jamie’s corpse, ‘Friends since second grade […] And then one of us gets himself into potentially big trouble, and now we’ve got to deal with it. We’ve got to test our loyalty against all odds. It’s kind of exciting. I feel like Chuck Norris, you know’. Clarissa, for her part, knows that she should inform the police, and in one scene she picks up the telephone and begins to do so, but she’s stopped by her lack of cognisance of who precisely she should call and what precisely she should tell them. In the film, the sense of liminality – being between childhood and adulthood – often manifests itself in a state of confusion or uncertainty. The young people in the film are unsure how to respond to John’s initial assertion that he has killed Jamie, taking this initially as a joke. They are even more unsure of how to respond to the sight of her corpse. When John takes Layne and Matt to where Jamie’s body is, Layne declares excitedly, ‘This is unreal, completely unreal’. Both Layne and Matt are blasé about their encounter with Jamie’s corpse, at least for the time being. Soon, however, Layne comes to see himself as the person who needs to rally the proverbial troops in order to protect John from being arrested for the killing. Layne references the myths of Hollywood films, suggesting that John’s crime offers a chance for Layne to step outside his mundane, dead-end existence: ‘It’s like some fucking movie, you know’, Layne says after seeing Jamie’s corpse, ‘Friends since second grade […] And then one of us gets himself into potentially big trouble, and now we’ve got to deal with it. We’ve got to test our loyalty against all odds. It’s kind of exciting. I feel like Chuck Norris, you know’. Clarissa, for her part, knows that she should inform the police, and in one scene she picks up the telephone and begins to do so, but she’s stopped by her lack of cognisance of who precisely she should call and what precisely she should tell them.

Later in the film, Matt and Clarissa discuss their confused response to the death of Jamie and their up-front confrontation with her corpse. ‘I kept seeing her [Jamie’s] face, Clarissa’, Matt tells his friend, ‘Didn’t you keep seeing her face? I mean, it affected me. Didn’t it affect you? I mean, we knew Jamie, right. And there she is, dead right in front of us. And even that close, we don’t even feel like we’ve lost anything. Least, I didn’t, and that got me the most’. To this, Clarissa responds: ‘I didn’t even cry for her, Matt. I mean, I cried when that guy in Bryan’s Song died. You’d at least figure I’d be able to cry for someone we hung around with’. ‘It’ll hit us’, Matt reasons, ‘I know it will. Probably at her funeral’. ‘Sometimes I think it’d be easier being dead’, Clarissa suggests. ‘That’s bullshit’, Matt tells her, ‘You couldn’t get stoned anymore’.

As Fred Pfeil reminds us, the issue at the heart of River’s Edge isn’t so much a ‘lack of response’ amongst the teenagers to Jamie’s murder, but rather a ‘lack of “proper”, conventional response’ (Pfeil, 1990: 192). For Ellen G Friedman and Corinne Squire, the responses of the teenagers within the film to the murder of Jamie ‘present various dissonant discourse of morality’: these ‘responses are vague or adopted from convenient models in movies and television’ (Friedman & Squire, 1998: 33). Friedman and Squire remind us of Layne’s assertion, upon discovering that John has killed Jamie and following Layne’s own suggestion that the group of teenagers held John evade capture by the police, that ‘We’ve got to test our loyalty against all odds [….] I feel like Chuck Norris’. Although the students emit a variety of responses to Jamie’s death – from apathy to curiosity – ‘the point is moral illiteracy, so that despite the variety of moral discourses put forward, each is cast as deficient or flawed’ (ibid.). As Fred Pfeil reminds us, the issue at the heart of River’s Edge isn’t so much a ‘lack of response’ amongst the teenagers to Jamie’s murder, but rather a ‘lack of “proper”, conventional response’ (Pfeil, 1990: 192). For Ellen G Friedman and Corinne Squire, the responses of the teenagers within the film to the murder of Jamie ‘present various dissonant discourse of morality’: these ‘responses are vague or adopted from convenient models in movies and television’ (Friedman & Squire, 1998: 33). Friedman and Squire remind us of Layne’s assertion, upon discovering that John has killed Jamie and following Layne’s own suggestion that the group of teenagers held John evade capture by the police, that ‘We’ve got to test our loyalty against all odds [….] I feel like Chuck Norris’. Although the students emit a variety of responses to Jamie’s death – from apathy to curiosity – ‘the point is moral illiteracy, so that despite the variety of moral discourses put forward, each is cast as deficient or flawed’ (ibid.).

John’s motives for killing Jamie are unclear, though in response to Layne’s question, ‘Why did you kill her?’, John asserts that ‘She [Jamie] was talking shit’. Layne presupposes that Jamie was saying something negative about Layne’s mother – who committed suicide, leaving John to live with his aunt. When Clarissa asks Layne why nobody is challenging John’s behaviour (‘That’s it? He murders Jamie and we just ignore it?’), Layne tells her, ‘He [John] had his reasons. She was shouting her mouth off about his mom’. Later in the film, John explains to Feck that he has a temper which he cannot control, offering a discussion of this within the framework of his personal philosophy which goes some way towards explaining how he may have killed Jamie: ‘I figure once you start fighting, you're always defending yourself. Me, I get in a fight, I go fucking crazy, you know? Everything goes black, and then I fucking explode, you know; like it's the end of the world. Who cares if this guy wastes me? I'll waste him first. The whole world's gonna blow up anyway. I might as well keep my pride. I got this philosophy: you do shit, and it's done, and then you die’.

John’s nonchalance towards violence and his antipathy towards the social contract are established very early in the film when he visits a convenience store and tries to buy alcohol. The employee of the store refuses to sell the alcohol to John, as he is underage, and in response Jogn spits angrily, ‘I don’t give a fuck about you, and I don’t give a fuck about laws, understand? Take the goddamn money, all right?’ This scene finds its mirror image later in the picture, when Matt visits the same store to buy beer for himself and Clarissa; the store employee refuses to sell the beer to the underage Matt, and into this situation walk both John and Feck (who are on a ‘beer run’). John asks Matt if the assistant is giving him any trouble before drawing Feck’s gun and pointing it at the assistant’s head: as this scene, which mirrors the earlier scene, suggests, John has gone beyond rhetoric. Feck witnesses John’s increasingly desperate behaviour with a sense of shock, which he expresses verbally (‘You know, you’re a crazy motherfucker. You know that?’, Feck tells John at one point). John’s nonchalance towards violence and his antipathy towards the social contract are established very early in the film when he visits a convenience store and tries to buy alcohol. The employee of the store refuses to sell the alcohol to John, as he is underage, and in response Jogn spits angrily, ‘I don’t give a fuck about you, and I don’t give a fuck about laws, understand? Take the goddamn money, all right?’ This scene finds its mirror image later in the picture, when Matt visits the same store to buy beer for himself and Clarissa; the store employee refuses to sell the beer to the underage Matt, and into this situation walk both John and Feck (who are on a ‘beer run’). John asks Matt if the assistant is giving him any trouble before drawing Feck’s gun and pointing it at the assistant’s head: as this scene, which mirrors the earlier scene, suggests, John has gone beyond rhetoric. Feck witnesses John’s increasingly desperate behaviour with a sense of shock, which he expresses verbally (‘You know, you’re a crazy motherfucker. You know that?’, Feck tells John at one point).

River’s Edge’s depiction of the ‘condition’ of adolescence runs counter to the myths perpetuated in many other American teen films of the era: Hunter’s film offers a body blow to the paradigms regarding the teenage experience established in, for example, John Hughes’ teen pictures of the 1980s. For Fred Pfeil, River’s Edge invokes and then subverts ‘the expectations’ associated with ‘the early-eighties “brat pack” film itself, in which typically a group of affluent yet troubled white teens (as in John Hughes The Breakfast Club, a paradigm of the species) draw out and resolve their individual problems through a kind of rough-and-tumble group therapy cum associated hijinx’ (Pfeil, op cit.: 193). The film also offers a subversive challenge to ‘the cheerfully scrubbed Spielbergian suburbs of Close Encounters of a [sic] Third Kind and E.T., in which broken homes and troubled families are magically reconstructed or restored with a single wave of a suitably high-tech, Disneyesque wand’ (ibid.). Emanuel Levy argues that River’s Edge ‘addresses the alienation and moral vacancy among American kids growing up in a drug-oriented, valueless culture’ (Levy, 1999: 286). In its subversion of the idealisation of adolescence, River’s Edge ‘has the disturbing quality of a collective fear—the cherished, eagerly awaited adolescence is presented as confusing and vacuous. Unlike most 1980s teenage sex comedies, this film doesn’t glamorize youth, instead depicting it as a bleak, aimless coming of age, a time of boredom, stupor, and waste’ (ibid.). Where most teenage pictures depict ‘the group [as] cohesive’, in River’s Edge ‘friendships are not based on any intimate interaction or substance’; but River’s Edge shares with a number of other youth pictures the depiction of adult figures ‘as irresponsible or indifferent’ (ibid.).

The film contains very few adult roles. The one teacher we see, Mr Burkewaite (Jim Metzler), is an ex-hippy who is so obsessed with his own past that he can't see what's happening in the present. ‘There was a meaning in the madness’, Burkewaite says in a monologue about the sixties which romanticises the counter-culture but which visibly bores the young people in his classroom, ‘a real and specific purpose’. To this, one of the students, Kevin (Richard Richcreek), asks, ‘But don’t you think violence is wrong?’ Kevin is quickly admonished by one of his peers, who declares, ‘Oh, fuck off, Kevin. Wasting pigs is radical, man’, whilst Burkewaite simply shakes his head in frustration at the impossibility of getting his message – vaguely packaged as it is – across to the students. The film contains very few adult roles. The one teacher we see, Mr Burkewaite (Jim Metzler), is an ex-hippy who is so obsessed with his own past that he can't see what's happening in the present. ‘There was a meaning in the madness’, Burkewaite says in a monologue about the sixties which romanticises the counter-culture but which visibly bores the young people in his classroom, ‘a real and specific purpose’. To this, one of the students, Kevin (Richard Richcreek), asks, ‘But don’t you think violence is wrong?’ Kevin is quickly admonished by one of his peers, who declares, ‘Oh, fuck off, Kevin. Wasting pigs is radical, man’, whilst Burkewaite simply shakes his head in frustration at the impossibility of getting his message – vaguely packaged as it is – across to the students.

Later in the film, after Jamie’s body has been discovered, we return to Burkewaite’s class as he discusses the situation with his students. Kevin expresses what the viewer of the film may be thinking (which perhaps is the socially-conditioned ‘correct’ response to John’s crime), but is soon shot down by Burkewaite. ‘I just want to say it’s horrible what those kids did’, Kevin says, ‘and the whole incident points up the fundamental moral breakdown of our society’. In response to this, Burkewaite – whose authority within the classroom has already been undermined in the earlier scene – states sarcastically, ‘Thank you, Kevin, for your insightful, self-righteous indignation’. Burkewaite expands on his feelings towards Jamie’s death, telling his students ‘You don’t give a damn. I don’t give a damn. Nobody in this class room gives a damn that she’s [Jamie is] dead. It gives us a chance to feel superior to point up a “fundamental moral breakdown in society”, but it doesn’t really affect us, does it? Because if it did, none of us would be in this class room right now. We’d be out on the street, half crazy from lack of sleep, hunting down Samson Tollet with a gun’. Burkewaite’s call to arms is ridiculed by one of his students, who asks simply, ‘Are we gonna be tested on this shit?’

Alongside Burkewaite’s presence, the only parents we spend time with (Matt's and Tim's) are constantly arguing and neglect their own children, or allow them to 'borrow' their stash of marijuana. In one scene, Matt’s mother asks Matt where he got the dope that he is smoking; ‘Don’t worry, it’s not yours’, is his reply. The police who investigate the murder of Jamie are unsympathetic, haranguing the only teenager to report the crime, Matt. ‘So you’re standing there, looking at your dead friend like it’s all some kind of big joke, right?’, the detective who interviews Matt asks, ‘Some adventure [….] What were you thinking about? Or where you even thinking?’ The detective behaves hostilely towards Matt and threatens to have him arrested as an accessory after the fact. In the midst of this, a number of the characters look towards Dennis Hopper's Feck, a paranoiac marijuana peddler who brags of having killed a girl once and claims to have been on the lam from the cops for twenty years as a result, as a sort of father figure. Alongside Burkewaite’s presence, the only parents we spend time with (Matt's and Tim's) are constantly arguing and neglect their own children, or allow them to 'borrow' their stash of marijuana. In one scene, Matt’s mother asks Matt where he got the dope that he is smoking; ‘Don’t worry, it’s not yours’, is his reply. The police who investigate the murder of Jamie are unsympathetic, haranguing the only teenager to report the crime, Matt. ‘So you’re standing there, looking at your dead friend like it’s all some kind of big joke, right?’, the detective who interviews Matt asks, ‘Some adventure [….] What were you thinking about? Or where you even thinking?’ The detective behaves hostilely towards Matt and threatens to have him arrested as an accessory after the fact. In the midst of this, a number of the characters look towards Dennis Hopper's Feck, a paranoiac marijuana peddler who brags of having killed a girl once and claims to have been on the lam from the cops for twenty years as a result, as a sort of father figure.

Layne turns towards Feck for help concealing John from the police, and Feck agrees. However, Feck soon comes to perceive a qualitative difference between his crime and the crime committed by Joh. ‘What’d you do?’, Feck asks John. ‘I killed Jamie’, John replies matter-of-factly. ‘It was an accident’, Layne adds unnecessarily. ‘Oh, I killed a girl once’, Feck declares, ‘It was no accident. Put the gun right to the back of her head and blew her brains right out the front. I was in love’. ‘I strangled mine’, John tells Feck. ‘Did you love her?’, Feck asks. ‘She was okay’, John replies. Later, John comments on Feck’s attachment to Ellie, asking the older man, ‘Hey, Feck. Are you a psycho or something?’ To this, Feck replies: ‘No, I’m normal. She’s [Ellie is] a doll. I know that [….] But you, you killed a girl, right? Are you a psycho?’ John responds: ‘Yeah, probably. What other excuse do I have?’

Soon, Feck begins to realise the precise differences between himself and John. Hanging out by the riverbank with Ellie and a six pack of beer, and some bullets for Feck’s gun which John has stolen from a hardware store, John fires the revolver into the darkness. Feck tells John that he needs a ‘reason’ to shoot the gun: ‘It’s got sentimental value’. ‘Is this the gun that you wasted the chick with?’, John asks matter-of-factly, ‘I bet you look back with pride, huh?’ Feck shakes his head, unwilling to revel in his crime: ‘It’s something I did’. ‘You wanted to show her who’s boss’, John offers, perhaps in reflection of his own murder of Jamie. ‘I don’t know if you can understand. I loved her’, Feck says. ‘So why’d you kill her? She tell you to eat shit?’, John asks. ‘No’, Feck says before repeating more firmly: ‘No!’ ‘Come on, Feck’, John says, ‘I’m with you. I killed a girl too. I wanted to show the world who’s boss [….] I didn’t need no gun. I did mine with my hands. I was right there. I was right on top of her. I was face to face. I wasn’t even mad, really. She didn’t look too surprised; just a little stoned [….] She couldn’t move; she couldn’t scream. I had total control of her. It all felt so real [….] She was dead there in front of me and I felt so fucking alive. Is that how you felt, Feck?’ Feck shows visible repulsion at John’s monologue before asserting, ‘Not quite’. ‘Will I end up like you, Feck?’, John asks, ‘You think I want that?’ ‘No, you don’t’, Feck tells him. Soon, Feck begins to realise the precise differences between himself and John. Hanging out by the riverbank with Ellie and a six pack of beer, and some bullets for Feck’s gun which John has stolen from a hardware store, John fires the revolver into the darkness. Feck tells John that he needs a ‘reason’ to shoot the gun: ‘It’s got sentimental value’. ‘Is this the gun that you wasted the chick with?’, John asks matter-of-factly, ‘I bet you look back with pride, huh?’ Feck shakes his head, unwilling to revel in his crime: ‘It’s something I did’. ‘You wanted to show her who’s boss’, John offers, perhaps in reflection of his own murder of Jamie. ‘I don’t know if you can understand. I loved her’, Feck says. ‘So why’d you kill her? She tell you to eat shit?’, John asks. ‘No’, Feck says before repeating more firmly: ‘No!’ ‘Come on, Feck’, John says, ‘I’m with you. I killed a girl too. I wanted to show the world who’s boss [….] I didn’t need no gun. I did mine with my hands. I was right there. I was right on top of her. I was face to face. I wasn’t even mad, really. She didn’t look too surprised; just a little stoned [….] She couldn’t move; she couldn’t scream. I had total control of her. It all felt so real [….] She was dead there in front of me and I felt so fucking alive. Is that how you felt, Feck?’ Feck shows visible repulsion at John’s monologue before asserting, ‘Not quite’. ‘Will I end up like you, Feck?’, John asks, ‘You think I want that?’ ‘No, you don’t’, Feck tells him.

The film’s cinematographer, Fred Elmes (who also shot the somewhat thematically similar Blue Velvet, a film which also featured Dennis Hopper in a key role, for David Lynch in the same year as River’s Edge), questioned director Tim Hunter’s decision to have Jamie’s corpse naked, suggesting that she should be ‘covered up a little bit’ (Elmes, quoted in LoBrutto, 1999: 165. However, Hunter argued that Jamie’s nudity was ‘the point’, and that it was ‘an Edward Weston nude, and that’s the way we’re going to approach it’ (Elmes, quoted in ibid.). Presumably, Hunter intended that the nudity would be presented – as in Weston’s nudes – as almost abstract formalism, devoid of any sexualisation. Fittingly, Hunter subsequently directed a number of episodes of Twin Peaks (1990-1), another narrative which was haunted by the spectre of a young woman’s cold, blue corpse – though Laura Palmer was ‘wrapped in plastic’ rather than naked, her eyes closed peacefully in comparison with Jamie’s unblinking stare into the camera.

For Barbara Jane Brickman, River’s Edge offers the polar opposite of a contemporaneous film like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (John Hughes, 1986). River’s Edge has more in common with films of the 1970s, Brickman argues, which question ‘the troubling divide between uninterested or neglectful parents and their emotionally vacant or disturbed offspring’ (Brickman, 2012: 213). To some extent, River’s Edge draws on the paradigms of the ‘bad seed’ pictures of the 1950s – films such as Melvyn LeRoy’s The Bad Seed (1956), that challenge our association of childhood and innocence by depicting young people participating in acts of violence or cruelty, often within a framework of a relationship with a disengaged or simply struggling parent/authority figure. In some ways, River’s Edge touches on similar thematic territory to Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue (1980), in which the affectlessness of the young protagonist (Linda Manz) is shown as being an outgrowth of her parents’ hippie background. River’s Edge similarly depicts its ineffectual authority figures (Burkewaite, Matt’s mother and stepfather) as being hold-overs from the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s. For Barbara Jane Brickman, River’s Edge offers the polar opposite of a contemporaneous film like Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (John Hughes, 1986). River’s Edge has more in common with films of the 1970s, Brickman argues, which question ‘the troubling divide between uninterested or neglectful parents and their emotionally vacant or disturbed offspring’ (Brickman, 2012: 213). To some extent, River’s Edge draws on the paradigms of the ‘bad seed’ pictures of the 1950s – films such as Melvyn LeRoy’s The Bad Seed (1956), that challenge our association of childhood and innocence by depicting young people participating in acts of violence or cruelty, often within a framework of a relationship with a disengaged or simply struggling parent/authority figure. In some ways, River’s Edge touches on similar thematic territory to Dennis Hopper’s Out of the Blue (1980), in which the affectlessness of the young protagonist (Linda Manz) is shown as being an outgrowth of her parents’ hippie background. River’s Edge similarly depicts its ineffectual authority figures (Burkewaite, Matt’s mother and stepfather) as being hold-overs from the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

‘Bad seed’ pictures continue today, of course, with examples such as Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin (2012); but during the 1970s the films often drew a connection between the ‘bad seed’ and supernatural phenomena (usually via a motif of demonic possession), which allowed a more biting dissection of the failures of parenthood. Notable examples include Robert Mulligan’s The Other (1972), Ed Hunt’s Bloody Birthday (1981) and, of course, William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973). Fred Pfiel suggests that this ‘supernatural bad seed’ motif is carried in River’s Edge through the character of Tim, who ‘calls up a […] long […] list of horror films built around the figure of the demonically possessed, insatiable child, from Rosemary’s Baby and The Exorcist to Firestarter’ (Pfeil, op cit.: 193). A comparison of The Exorcist with River’s Edge may seem outwardly absurd, but in terms of the films’ inner forms there are a number of similarities between them – in their depiction of a child (or in the case of River’s Edge, numerous children) who, with largely absent parent/s and no guiding system of morality, begins to ‘act out’. As Brickman argues, in River’s Edge the ‘“generation gap” has become an abyss […] and representatives of the much-lauded 1960s generation of youth have become the most dangerous or ineffectual of adults’ (ibid.).

The film is uncut and runs for 99:40 mins.

Video

Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, this 1080p presentation of River’s Edge uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film’s photography, by Fred Elmes, is exceptional; as noted above, Elmes contributed some similarly good photography to David Lynch’s Blue Velvet within a year of this picture being made. The palette is drab, the compositions filled with muted, autumnal colours. The film opens with a grainy, monochrome post-processed shot of the river before seguing into the colour 35mm photography which makes up the bulk of the film (though John’s flashback to the murder of Jamie, with his hands wrapped tightly around her throat, seems to be shot on faster stock or perhaps post-processed in a way which gives it ‘punchier’ contrast and a coarser grain structure). A good level of detail is on display in this presentation, married with Elmes’ tendency to stage shots in depth. The presentation has a slightly ‘digital’ look here and there, with some shots displaying a smoothness which may be inherent in the materials but could also be evidence of noise reduction. Nevertheless, this isn’t an overriding characteristic of the presentation. Good contrast levels result in an image which is for the most part nicely-balanced; and finally, a very strong encode ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film. Taking up approximately 20Gb of space on its disc, this 1080p presentation of River’s Edge uses the AVC codec and is in the film’s intended aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film’s photography, by Fred Elmes, is exceptional; as noted above, Elmes contributed some similarly good photography to David Lynch’s Blue Velvet within a year of this picture being made. The palette is drab, the compositions filled with muted, autumnal colours. The film opens with a grainy, monochrome post-processed shot of the river before seguing into the colour 35mm photography which makes up the bulk of the film (though John’s flashback to the murder of Jamie, with his hands wrapped tightly around her throat, seems to be shot on faster stock or perhaps post-processed in a way which gives it ‘punchier’ contrast and a coarser grain structure). A good level of detail is on display in this presentation, married with Elmes’ tendency to stage shots in depth. The presentation has a slightly ‘digital’ look here and there, with some shots displaying a smoothness which may be inherent in the materials but could also be evidence of noise reduction. Nevertheless, this isn’t an overriding characteristic of the presentation. Good contrast levels result in an image which is for the most part nicely-balanced; and finally, a very strong encode ensures that the film retains the structure of 35mm film.

In sum, it’s a very pleasing presentation of the film, a clear improvement over the DVD releases that have been available.

NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is clear throughout and possesses the sense of range that it should. Though it’s by no means a ‘showy’ track, it displays a sense of depth when it’s needed. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included.

Extras

The disc includes:

- an audio commentary by Tim Hunter. Hunter’s commentary for the picture is informative and engaging, reflecting on some of the casting decisions and Hunter’s approach to Neal Jiminez’s screenplay. - an audio commentary by Tim Hunter. Hunter’s commentary for the picture is informative and engaging, reflecting on some of the casting decisions and Hunter’s approach to Neal Jiminez’s screenplay.

- an introduction by Richard Linklater (7:51). Linklater is the artistic director of the Austin Film Society, which screened River’s Edge as part of its ‘Jewels in the Wasteland: A Trip Through 1980s Cinema’ earlier in 2015. Linklater provided an introduction to the film, presented here, and appeared in a question and answer session after it, also included on this disc. In his introduction, Linklater discusses the relationship between River’s Edge and Tim Hunter’s previous film Over the Edge, citing both pictures as counterpoints to the John Hughes movies of the era. Regarding River’s Edge in particular, Linklater observes, ‘It’s a bummer subject and it’s right there from the beginning’.

Linklater praises the work of the cast, and discusses some of the reasons why a film like River’s Edge would not be made in today’s climate. He suggests the picture is a product of the ‘fatalistic thinking’ of the 1980 – ‘around the edges of the veneer of an industry that is trying to be a very different kind of culture’.

- a Q&A with Richard Linklater (24:31). Recorded at the same event, this features Linklater in a question and answer session with the audience who attended the screening of the film. It’s far less structured than Linklater’s introduction, as you might expect, and covers some of the same ground – with Linklater offering his personal perspective on US cinema of the 1980s.

- The Austin Film Society Experience. Selecting this option in the menu allows the viewer to watch, in sequence, Linklater’s introduction, the film itself, and then the Q&A with Linklater.

- the film’s trailer (1:59).

Overall

River’s Edge is an uncompromising film. It’s beautifully shot and has a lot to say about American society of the 1980s, and specifically youth culture of the era, that still seems relevant today – arguably more so. There are aspects of the film which grate on some viewers: for example, Crispin Glover’s performance. Nevertheless, the picture is a fine antidote to the teen comedies of the 1980s that seem to be more firmly embedded in the collective unconscious than darker pictures about adolescence during the era such as River’s Edge, Blue Velvet and Rumble Fish (Francis Ford Coppola, 1983). River’s Edge is an uncompromising film. It’s beautifully shot and has a lot to say about American society of the 1980s, and specifically youth culture of the era, that still seems relevant today – arguably more so. There are aspects of the film which grate on some viewers: for example, Crispin Glover’s performance. Nevertheless, the picture is a fine antidote to the teen comedies of the 1980s that seem to be more firmly embedded in the collective unconscious than darker pictures about adolescence during the era such as River’s Edge, Blue Velvet and Rumble Fish (Francis Ford Coppola, 1983).

The presentation of River’s Edge on this Blu-ray is pleasing: it’s certainly a big improvement over the film’s various DVD releases. The film itself is accompanied by some good contextual material too – particularly the commentary by Tim Hunter, though Richard Linklater’s introduction goes a good way to establishing a context for the picture. It’s a very good release, and pleasing to see a picture such as this hit the Blu-ray format in the UK.

References:

Brickman, Barbara Jane, 2012: New American Teenagers: The Lost Generation of Youth in 1970s Film. London: Continuum

Caputi, Jane, 1991: ‘Psychic Numbing, Radical Futurelessness, and Sexual Violence in the Nuclear Film’. In: Anisfield, Nancy (ed), 1991: The Nightmare Considered: Critical Essays on Nuclear War Literature. Bowling Green State University Popular Press: 58-70

Friedman, Ellen G & Squire, Corinne, 1998: Morality USA. University of Minnesota Press

Levy, Emanual, 1999: Cinema of Outsiders: The Rise of American Independent Film. New York University Press

LoBrutto, Vincent, 1999: Principal Photography: Interviews with Feature Film Cinematographers. Connecticut: Praeger Publishers

Pfeil, Fred, 1990: Another Tale to Tell: Politics & Narrative in Postmodern Culture. London: Verso

|