|

|

Deep Red AKA Profondo rosso AKA The Hatchet Murders

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (31st January 2016). |

|

The Film

Profondo rosso AKA Deep Red (Dario Argento, 1975)  As a genre or style of cinema, the thrilling all�italiana (or giallo all�italiana) is difficult to pin down, largely owing to tensions in the ways in which the thrilling is perceived by different audiences. Chief among these is the problem of definition and identification. English-speaking fans of Italian-style thrillers tend to use the label giallo to identify such films, whereas to Italian audiences a giallo is of course a thriller of any type, regardless of its country of origin. For Italian audiences the label giallo may denote any kind of thriller, regardless of its content or context of production; thus the label giallo may be applied to films as diverse as Hitchcock�s Stage Fright (1950), and John Huston�s The Maltese Falcon (1941). However, for English-language cinephiles the term giallo has become indelibly associated with a very specific subgroup of Italian-produced thrillers made during the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. Italian audiences tend to refer to these films as examples of the thrilling or thrilling all�italiana/giallo all�italiana (Italian-style thrillers): in other words, thrillers with a very specific Italian �flavour�. As Philippe Met suggests, approaches to understanding the giallo/thrilling all�italiana are complicated by �existing discrepancies of a semantic or taxonomic nature� (2006: 196). Met highlights the fact that there is irony in the fact that within Italy, �in the very country in which it [the giallo/thrilling all�italiana] originated, the all�italiana [Italian-style] specificity of the genre� is largely �subsumed by [�] a much broader understanding of the giallo designation as coextensive with crime cinema� more generally, �cutting across national boundaries and the typological spectrum�; whilst in Britain and America, on the other hand, the giallo is seen as an exclusively Italian product, to the extent that debates exist as to whether �one can viably and legitimately stretch it to create an �American giallo��, for example (ibid.). As a genre or style of cinema, the thrilling all�italiana (or giallo all�italiana) is difficult to pin down, largely owing to tensions in the ways in which the thrilling is perceived by different audiences. Chief among these is the problem of definition and identification. English-speaking fans of Italian-style thrillers tend to use the label giallo to identify such films, whereas to Italian audiences a giallo is of course a thriller of any type, regardless of its country of origin. For Italian audiences the label giallo may denote any kind of thriller, regardless of its content or context of production; thus the label giallo may be applied to films as diverse as Hitchcock�s Stage Fright (1950), and John Huston�s The Maltese Falcon (1941). However, for English-language cinephiles the term giallo has become indelibly associated with a very specific subgroup of Italian-produced thrillers made during the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s. Italian audiences tend to refer to these films as examples of the thrilling or thrilling all�italiana/giallo all�italiana (Italian-style thrillers): in other words, thrillers with a very specific Italian �flavour�. As Philippe Met suggests, approaches to understanding the giallo/thrilling all�italiana are complicated by �existing discrepancies of a semantic or taxonomic nature� (2006: 196). Met highlights the fact that there is irony in the fact that within Italy, �in the very country in which it [the giallo/thrilling all�italiana] originated, the all�italiana [Italian-style] specificity of the genre� is largely �subsumed by [�] a much broader understanding of the giallo designation as coextensive with crime cinema� more generally, �cutting across national boundaries and the typological spectrum�; whilst in Britain and America, on the other hand, the giallo is seen as an exclusively Italian product, to the extent that debates exist as to whether �one can viably and legitimately stretch it to create an �American giallo��, for example (ibid.).

Related to this issue of labeling is the debate, similar to that which exists in studies of American films noir, as to whether these films constitute a genre or may instead be considered a more loosely-defined �style�. Attempts at structuralist analysis of the thrilling all�italiana may of course be made (and have been conducted in the past), but the Italian-style thriller is a wildly diverse subcategory of filmmaking, running the gamut from erotic melodramas and political thrillers to more outr� supernatural thrillers. Like film noir, the giallo (or thrilling all�italiana) can perhaps best be considered as a �style� rather than a genre: although the pictures very often (but not always) feature recurring visual elements, in narrative structure and thematic concerns the films are actually incredibly diverse. In terms of narrative �types�, the thrilling all�italiana encompasses paranoid political thrillers (La corta notte della bambole di vetro/Short Night of the Glass Dolls, Aldo Lado, 1971), rural psychosexual terror pictures filled with creeping dread (La casa dalle finestre che ridono/The House with Laughing Windows, Pupi Avati, 1975), cosmopolitan �woman-in-peril� melodramas (Le foto proibite di una signora per bene/The Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion, Luciano Ercoli, 1970) that seem to take their cue from films noir like Joseph Losey�s The Prowler (1951), and �impure� hybrids such as La polizia chiede aiuto (What Have They Done to Your Daughters?, Massimo Dallamano, 1974), a picture which marries the domestic peril of the thrilling all�italiana with the procedural elements of the poliziesco all�italiana (Italian-style police films).  Furthermore, structuralist approaches to the Italian thriller that attempt to define it as a genre with a relatively fixed outer form (an iconography, or a series of visual signifiers) and inner form (a set of themes and narrative conventions) are often undermined by a sense of confirmation bias: that the outliers, the films which don�t conform to the Bava-Argento �template� (ie, the black gloved assassin, the whodunit structure), are either ignored or contorted to fit the hypothesis. Growing out of this, perhaps, is the suggestion that the Italian language designator (thrilling all�italiana/giallo all�italiana) suggests a style (the �Italian-style� of the name ascribed to this group of films); whereas, on the other hand, English-speaking fans arguably use the label giallo to denote a genre that, for them, is perceived as possessing both an �inner form� and an �outer form�. Furthermore, structuralist approaches to the Italian thriller that attempt to define it as a genre with a relatively fixed outer form (an iconography, or a series of visual signifiers) and inner form (a set of themes and narrative conventions) are often undermined by a sense of confirmation bias: that the outliers, the films which don�t conform to the Bava-Argento �template� (ie, the black gloved assassin, the whodunit structure), are either ignored or contorted to fit the hypothesis. Growing out of this, perhaps, is the suggestion that the Italian language designator (thrilling all�italiana/giallo all�italiana) suggests a style (the �Italian-style� of the name ascribed to this group of films); whereas, on the other hand, English-speaking fans arguably use the label giallo to denote a genre that, for them, is perceived as possessing both an �inner form� and an �outer form�.

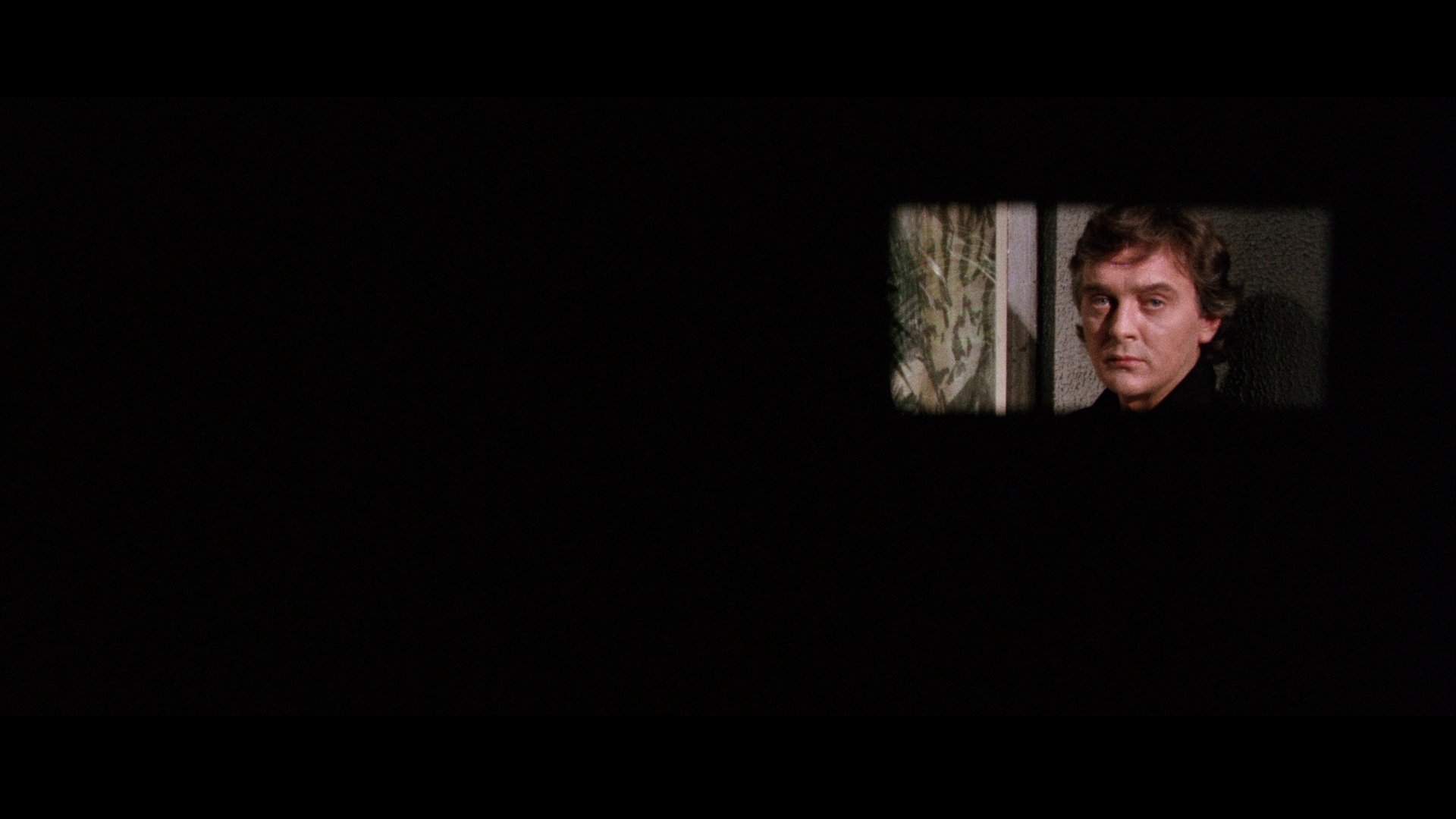

Alongside Mario Bava�s Sei donne per l�assassino (Blood and Black Lace, 1964), Dario Argento�s Deep Red (1975) is arguably the picture that characterises the qualities that English-speaking fans tend to associate with the giallo all�italiana: Argento�s film has a whodunit structure and features a killer who is clad in black (complete with black gloves and a fedora), an amateur sleuth who has witnessed a murder but struggles to identify a key detail which will help them to solve the crime, and twists of logic that incorporate elements which touch on the supernatural. English-speaking fans of the thrilling all�italiana tend to privilege the giallo �sulla stesso filone Argento� (�in the style of Argento�) as the style most closely associated with Italian thrillers of the 1970s and 1980s, and it�s in Deep Red that this style was consolidated. The film marked a turning point in Argento�s career, and though in terms of narrative structure there�s a continuation with his �animal trilogy� of thrilling all�italiana pictures (his debut feature L�uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970; Il gatto a nove code/Cat O�Nine Tails, 1971; and Quattre mosche di velluto grigio/Four Flies on Grey Velvet, 1971), in its incorporation of vaguely supernatural elements Deep Red pushes into territory that Argento would explore more aggressively in later films like Suspiria (1977) and Inferno (1980). Danny Shipka, for example, has suggested that Deep Red marked the beginnings of Argento�s tendency to blur �the boundaries between a thriller and a horror film� (Shipka, 2011: 95).  Beginning with an elliptical depiction of a murder in a domestic setting (signified as such by the d�cor and a Christmas tree in the background), Deep Red focuses on Marcus Daly (David Hemmings), a British pianist who is teaching music in Rome. Marc is dragged unwittingly into a mystery when his downstairs neighbour Helga Ullman (Macha Meril), a psychic visiting Rome, is brutally murdered after declaring, during a parapsychology conference, that one of the attendees is a murderer. Ullman is staying in the apartment below Marc�s, and talking with his friend Carlo (Gabriele Lavia) � who lives with his mother Marta (Clara Calamai) � outside the building, Marc witnesses Ullman�s murder. Marc rushes to Ullman�s aid but is too late to save her. Beginning with an elliptical depiction of a murder in a domestic setting (signified as such by the d�cor and a Christmas tree in the background), Deep Red focuses on Marcus Daly (David Hemmings), a British pianist who is teaching music in Rome. Marc is dragged unwittingly into a mystery when his downstairs neighbour Helga Ullman (Macha Meril), a psychic visiting Rome, is brutally murdered after declaring, during a parapsychology conference, that one of the attendees is a murderer. Ullman is staying in the apartment below Marc�s, and talking with his friend Carlo (Gabriele Lavia) � who lives with his mother Marta (Clara Calamai) � outside the building, Marc witnesses Ullman�s murder. Marc rushes to Ullman�s aid but is too late to save her.

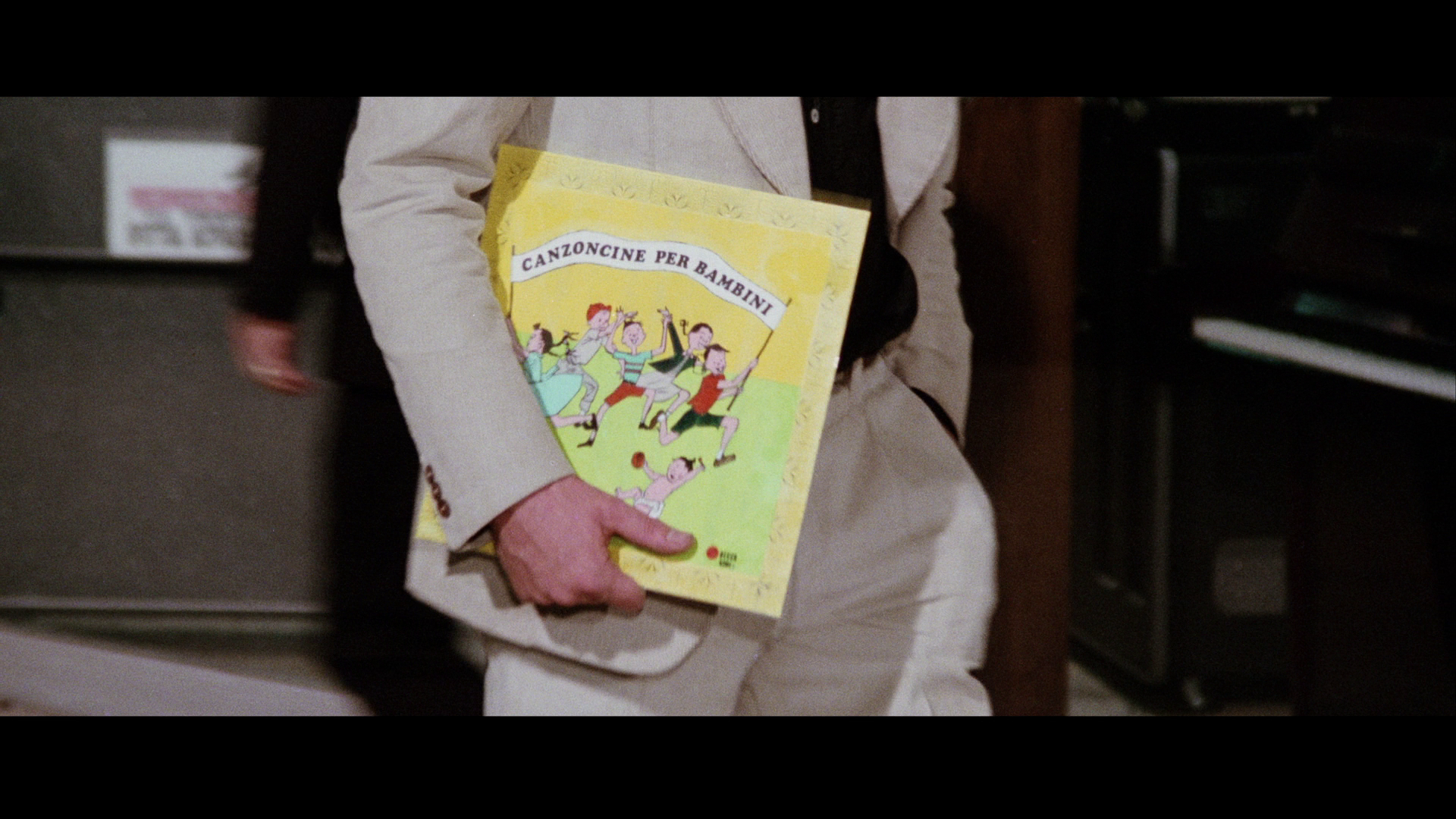

Whilst being interviewed by the police, Marc meets journalist Gianna Brezzi (Daria Nicolodi). Gianna takes Marc�s photograph, which the next day is published alongside an article which suggests that Marc may be able to identify the killer. Marc complains to Gianna that the publication of the article and the photograph may make him a target for the murderer. (�It�s always nice to let the murderer know who you are�, he tells her dryly.) However, the couple grow closer and eventually form a romantic relationship. One evening, whilst composing music at his piano Marc hears the same child�s lullaby that accompanied the murder which takes place during the film�s opening titles. Marc discovers that someone else, the murderer, is within his apartment. He manages to warn the murderer away by telephoning Gianna, but the killer whispers a promise to Marc: �I�ll kill you anyway, sooner or later�. Marc becomes determined to identify the lullaby he heard that night, and buys an LP of children�s lullabies. With the help of Ullman�s friend Professor Giordano (Giauco Mauri), the lullaby leads Marc to a book of folklore, The Modern Ghost and the Black Legends of Today, which contains a story about �a haunted house from which the neighbours sometimes hear singing, like a child�. The house, it�s said, is a place where an act of violence took place which is being replayed by the spirits that reside there.  To identify the specific house associated with this legend, Marc decides to interview the author of the book, Amanda Righetti (Giuliana Calandra). However, he is beaten to the punch by the killer, who drowns Righetti in a bathtub filled with scolding hot water. Arriving at Righetti�s home shortly after the departure of the killer, Marc discovers the body of Righetti and informs Giordano of her death. In desperation for another clue, Marc rips from Righetti�s book a page containing a photograph of the supposedly haunted house to a horticulturalist, who identifies a rare genus of plant outside the building; this helps Marc to locate the house about which Righetti wrote in her volume on folklore. Visiting the house, Marc discovers that it is derelict. Underneath some peeling plaster, Marc discovers a childlike drawing depicting a murder � the murder that the film�s audience will recognise as the murder that is committed during the opening title�s sequence. To identify the specific house associated with this legend, Marc decides to interview the author of the book, Amanda Righetti (Giuliana Calandra). However, he is beaten to the punch by the killer, who drowns Righetti in a bathtub filled with scolding hot water. Arriving at Righetti�s home shortly after the departure of the killer, Marc discovers the body of Righetti and informs Giordano of her death. In desperation for another clue, Marc rips from Righetti�s book a page containing a photograph of the supposedly haunted house to a horticulturalist, who identifies a rare genus of plant outside the building; this helps Marc to locate the house about which Righetti wrote in her volume on folklore. Visiting the house, Marc discovers that it is derelict. Underneath some peeling plaster, Marc discovers a childlike drawing depicting a murder � the murder that the film�s audience will recognise as the murder that is committed during the opening title�s sequence.

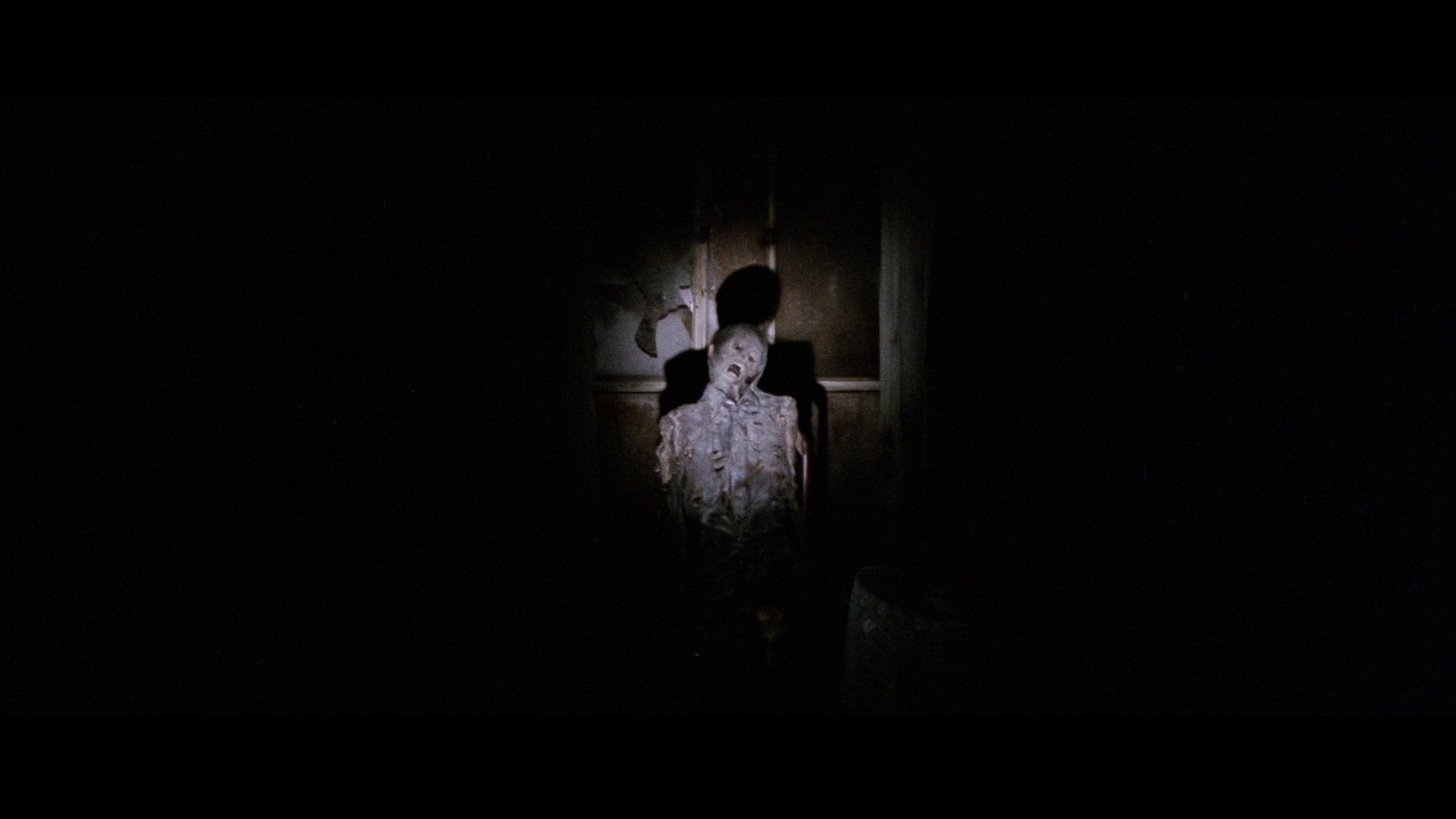

Giordano is killed. After discovering of Giordano�s death, Marc makes a realisation about the house: there seems to be a walled-up room. He returns to the house at night and investigates, breaking down a wall to discover a dessicated corpse in the concealed room. However, Marc is attacked by an unknown assailant and the house is set alight. Gianna drags Marc out of the building and takes him to the home of the caretaker, from where they call the fire brigade. In the caretaker�s house, Marc sees a similar drawing in the bedroom of the caretaker�s daughter Olga (Nicoletta Elmi). Olga has copied the drawing from one that she found in the school archives. Marc investigates the school at night and discovers the drawing; he is shocked to discover that it is signed by his friend Carlo. In Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980, Danny Shipka suggests that Argento�s debut picture, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, was a watershed film in Italian popular cinema, �mark[ing] the beginning of a decade in which the quaintness of previous Italian filmmakers would be replaced by those who gave a gritty, graphic exploration of a society that�s no longer safe� (Shipka, 2011: 84). In contrast with the thrilling all�italiana films of Mario Bava, which Shipka argues �always had an air of quaintness about them�, Argento�s Italian-style thrillers �were cool, modern and hip�: Bava�s violence �was theatrical and over-the-top�, whereas the violence of Argento�s pictures �seemed all too real, rooted in the headlines of the day which made them all the more terrifying� (ibid.). By paring violence down to �the straight kill, nothing but leather and a sharp knife or razor here�, Argento�s pictures emphasised �the pure sexual violence that is the root of gialli� (ibid.).  As if to reinforce the film�s title, the colour red proliferates throughout the film. As the camera (sharing the killer�s point-of-view) enters the auditorium where the parapsychology conference is being held, we pass through red curtains; the auditorium itself is decorated in red, the chairs lined in red and the backdrop of the stage a vivid crimson too. Of course, the deepest red is seen within the blood that abounds within the film�s murder scenes � and the pool of blood which Marc is left staring into at the end of the picture. The scenes of violence within Deep Red are spectacular. Ullman�s murder begins with the psychic in her apartment. She is on the telephone. The set contains indices of Ullman�s Jewish identity, including a table in the shape of a Star of David which casts a deep shadow across the floor. Ullman hears the children�s lullaby that has, within the film, already been associated with the murder depicted within the opening titles sequence. The doorbell rings. Ullman answers and is attacked with a meat cleaver, which is buried deep into her shoulder. Pounding, bassy music fills the audio track. The killer, dressed all in black (black gloves, a black fedora, black clothes) enters. As Marc arrives to rescue Ullman, whose head he has seen thrust spectacularly through the window of her apartment, he races along a hallway lined with various Edvard Munch-style paintings. (The psychological symbolism of Munch�s technique seems to have been an inspiration for much of Deep Red�s visual design.) The murders of Righetti and Giordano are equally elaborate. In her home, Righetti discovers a doll hanging by its neck, and the discovery of this bizarre item immediately precedes an attack upon Righetti by the killer, who drowns Righetti in a bathtub of scolding hot water. Giordano�s murder is similarly preceded by the appearance of a toy; in this instance, a bizarre clockwork �walking� doll which is accompanied by audible cackling and a whispered voice. As the doll approaches, Giordano lashes out at it with an ornate letter opener. Before the killer administers the death blow to Giordano by driving the same letter opener through his neck, Giordano�s teeth are bashed out on a stone mantelpiece and an ornate wooden desk; the imagery is deliberately Freudian. After Giordano�s death, the camera lingers on the image of the doll lying on the wooden floor, the doll�s head smashed into a number of pieces. Like the image of the hanged doll which immediately precedes the killer�s attack upon Righetti, this is a highly symbolic (in the manner of Edvard Munch) image that openly hints at a theme of child abuse and trauma directed towards the concept of childhood. As if to reinforce the film�s title, the colour red proliferates throughout the film. As the camera (sharing the killer�s point-of-view) enters the auditorium where the parapsychology conference is being held, we pass through red curtains; the auditorium itself is decorated in red, the chairs lined in red and the backdrop of the stage a vivid crimson too. Of course, the deepest red is seen within the blood that abounds within the film�s murder scenes � and the pool of blood which Marc is left staring into at the end of the picture. The scenes of violence within Deep Red are spectacular. Ullman�s murder begins with the psychic in her apartment. She is on the telephone. The set contains indices of Ullman�s Jewish identity, including a table in the shape of a Star of David which casts a deep shadow across the floor. Ullman hears the children�s lullaby that has, within the film, already been associated with the murder depicted within the opening titles sequence. The doorbell rings. Ullman answers and is attacked with a meat cleaver, which is buried deep into her shoulder. Pounding, bassy music fills the audio track. The killer, dressed all in black (black gloves, a black fedora, black clothes) enters. As Marc arrives to rescue Ullman, whose head he has seen thrust spectacularly through the window of her apartment, he races along a hallway lined with various Edvard Munch-style paintings. (The psychological symbolism of Munch�s technique seems to have been an inspiration for much of Deep Red�s visual design.) The murders of Righetti and Giordano are equally elaborate. In her home, Righetti discovers a doll hanging by its neck, and the discovery of this bizarre item immediately precedes an attack upon Righetti by the killer, who drowns Righetti in a bathtub of scolding hot water. Giordano�s murder is similarly preceded by the appearance of a toy; in this instance, a bizarre clockwork �walking� doll which is accompanied by audible cackling and a whispered voice. As the doll approaches, Giordano lashes out at it with an ornate letter opener. Before the killer administers the death blow to Giordano by driving the same letter opener through his neck, Giordano�s teeth are bashed out on a stone mantelpiece and an ornate wooden desk; the imagery is deliberately Freudian. After Giordano�s death, the camera lingers on the image of the doll lying on the wooden floor, the doll�s head smashed into a number of pieces. Like the image of the hanged doll which immediately precedes the killer�s attack upon Righetti, this is a highly symbolic (in the manner of Edvard Munch) image that openly hints at a theme of child abuse and trauma directed towards the concept of childhood.

The opening murder identifies the home as a site of trauma, destroying the perceived sanctity of the domestic space. The film�s pounding main titles theme is interrupted by a child�s lullaby, and Argento presents the film�s viewer with an oblique depiction of a murder. The camera is placed on the floor; the murder is acted out in silhouette against the far wall. A Christmas tree can be seen in the room, its presence acting as an index of both the domestic setting and the time of year; the connotations of the Christmas tree are placed in juxtaposition with the cruelty of the murder that takes place in the same room. Later, Marc visits the same house in which this murder took place and it�s derelict, devoid of care, love and hope; the symbolism attached to houses and other buildings is a theme that is explored in many later Argento films, including (most obviously) Suspiria and Inferno, but also more subtly in other pictures such as Phenomena (1985). Like the houses in those pictures, the abandoned house in Deep Red slowly reveals its secrets to Marc: the child�s mural hidden behind peeling plaster, and later the dessicated corpse of the murder victim hidden in a walled-in room. Marc�s exploration of the house may be taken as a symbol of the investigative process itself: the uncovering of secrets and past traumas during Marc�s investigation into Ullman�s murder is mirrored in the ways in which the house gradually reveals its secrets to him visually. The opening murder is a primal scene, a moment of trauma to which the film returns again and again, concealed within the memory in the same manner in which the corpse of the victim is sealed within a room of the house: this past crime resurfaces in the repeated appearance of the lullaby-like musical motif, and in the iconography of the child�s drawing on the wall of the derelict house (and in the archives of the school). The opening murder identifies the home as a site of trauma, destroying the perceived sanctity of the domestic space. The film�s pounding main titles theme is interrupted by a child�s lullaby, and Argento presents the film�s viewer with an oblique depiction of a murder. The camera is placed on the floor; the murder is acted out in silhouette against the far wall. A Christmas tree can be seen in the room, its presence acting as an index of both the domestic setting and the time of year; the connotations of the Christmas tree are placed in juxtaposition with the cruelty of the murder that takes place in the same room. Later, Marc visits the same house in which this murder took place and it�s derelict, devoid of care, love and hope; the symbolism attached to houses and other buildings is a theme that is explored in many later Argento films, including (most obviously) Suspiria and Inferno, but also more subtly in other pictures such as Phenomena (1985). Like the houses in those pictures, the abandoned house in Deep Red slowly reveals its secrets to Marc: the child�s mural hidden behind peeling plaster, and later the dessicated corpse of the murder victim hidden in a walled-in room. Marc�s exploration of the house may be taken as a symbol of the investigative process itself: the uncovering of secrets and past traumas during Marc�s investigation into Ullman�s murder is mirrored in the ways in which the house gradually reveals its secrets to him visually. The opening murder is a primal scene, a moment of trauma to which the film returns again and again, concealed within the memory in the same manner in which the corpse of the victim is sealed within a room of the house: this past crime resurfaces in the repeated appearance of the lullaby-like musical motif, and in the iconography of the child�s drawing on the wall of the derelict house (and in the archives of the school).

The lullaby becomes an important element of the film. It is played by the killer, on a portable reel to reel tape deck, prior to the murders. The music itself is indexical of childhood, and is connected to the domestic space in which the murder depicted in the opening titles sequence takes place. After hearing it for the first time when the killer stalks him in his own apartment, Marc becomes determined to identify the lullaby and buys an LP of children�s songs. Giordano rightly suggests to Marc that the �song might be the leitmotif of the crimes�, part of the killer�s need to �recreate the specific conditions which trigger the release of all his pent-up madness�. Through its connection with the murders, the innocent-sounding lullaby becomes symbolic of the corruption of idealised myths surrounding childhood and the family, and the shattering of notions of �innocence�. This is heightened by the objects associated with childhood that are encountered at each crime scene: the mechanical doll whose appearance precedes Giordano�s murder, and the doll that Righetti finds hanging from her ceiling just prior to her attack by the killer. This theme of the corruption of childhood (or our perception of it) is pushed to the foreground when Marc encounters the caretaker of the derelict house. Ordering his young daughter Olga (Nicoletta Elmi) to show Marc to the house, the man suddenly strikes the child sharply, causing Marc to look on in shock. We presume that the father is abusive; the young girl simply tells Marc, �My father�s just a little crazy�. However, the camera slowly tilts down from the father�s face to reveal a lizard cruelly pinned to the floor, an act for which Olga is responsible � the spite of her treatment of the lizard undercutting the audience�s perception of the cruelty of her father, smashing preconceptions of childhood �innocence�. Later, when Marc sees a similar drawing to that he encountered in the house pinned to the wall of Olga�s bedroom, Olga�s father tells Marc matter-of-factly, �She just loves to do horrible things. You should see what she does to lizards�.  Peter Bondanella has argued that �Argento�s horror films are often a variant of the detective film in which the maniac killer matches wits with an investigator trying to discover the truth behind the horrifying crimes that are depicted in graphical detail� (Bondanella, 2009: 420). Deep Red is a picture which emblematises this approach, with its plot that �focuses upon a conventional Freudian murder drama of a traumatic event in the past [�] that produces a succession of horrific murders in the present� (ibid.). Bondanella also compares Argento�s use of �aging actresses who were once femme fatales in [his] horror films�, a trend which began with Deep Red, with Robert Aldrich�s casting of Bette Davis in Hush� Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). In later films, Argento would cast older actresses such as Alida Valli and Joan Bennett (in Suspiria) in reference to both Italian and Hollywood cinema � particularly films noir � of prior years. (In Opera, 1987, Argento cast Vanessa Redgrave, David Hemmings� co-star in Antonioni�s 1966 picture Blow-Up, but Redgrave bowed out of the production at the last minute.) Here in Deep Red, Argento casts Clara Calamai, who essayed the femme fatale role in Luchino Visconti�s Ossessione (1944, an adaptation of James M Cain�s The Postman Always Rings Twice), in a key role. In fact, Ellen Nerenberg posits that Argento�s four early examples of the thrilling combine elements of the Italian-style thriller and film noir, whereas the pictures that Argento made after Deep Red retained aspects of the thrilling all�italiana whilst allying themselves more closely with the supernatural horror film (Nerenberg, 2012: 74). Nerenberg compares Argento�s post-Deep Red films with the novels of Italian crime writers Carlo Lucarelli and Andrea Pinketts, in that like the work of those authors Argento�s films featured �monstrous figures [who] tend to bleed together and blur generic distinction so that, for example, a film might be a giallo but the catalyst for its serial killer may be supernatural� (ibid.). In interview, Argento has suggested that the perceived line dividing his �naturalistic� early thrillers and his later supernatural pictures is �an artificial distinction: I don�t see a great difference between them. The realistic pictures are not very realistic, even though they�re about psychopaths rather than witches� (Argento, quoted in ibid.: 75). In the films Argento made after Deep Red, Bondanella suggests, Argento came increasingly to combine the plotting of detective stories with �B movie gore� and baroque studio sets, incorporating violence which �becomes completely gratuitous, irrational, and without any coherent logic�; the cumulative effect, Bondanella says, is �stylish yet chillingly effective� (Bondanella, op cit.: 420). Peter Bondanella has argued that �Argento�s horror films are often a variant of the detective film in which the maniac killer matches wits with an investigator trying to discover the truth behind the horrifying crimes that are depicted in graphical detail� (Bondanella, 2009: 420). Deep Red is a picture which emblematises this approach, with its plot that �focuses upon a conventional Freudian murder drama of a traumatic event in the past [�] that produces a succession of horrific murders in the present� (ibid.). Bondanella also compares Argento�s use of �aging actresses who were once femme fatales in [his] horror films�, a trend which began with Deep Red, with Robert Aldrich�s casting of Bette Davis in Hush� Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964). In later films, Argento would cast older actresses such as Alida Valli and Joan Bennett (in Suspiria) in reference to both Italian and Hollywood cinema � particularly films noir � of prior years. (In Opera, 1987, Argento cast Vanessa Redgrave, David Hemmings� co-star in Antonioni�s 1966 picture Blow-Up, but Redgrave bowed out of the production at the last minute.) Here in Deep Red, Argento casts Clara Calamai, who essayed the femme fatale role in Luchino Visconti�s Ossessione (1944, an adaptation of James M Cain�s The Postman Always Rings Twice), in a key role. In fact, Ellen Nerenberg posits that Argento�s four early examples of the thrilling combine elements of the Italian-style thriller and film noir, whereas the pictures that Argento made after Deep Red retained aspects of the thrilling all�italiana whilst allying themselves more closely with the supernatural horror film (Nerenberg, 2012: 74). Nerenberg compares Argento�s post-Deep Red films with the novels of Italian crime writers Carlo Lucarelli and Andrea Pinketts, in that like the work of those authors Argento�s films featured �monstrous figures [who] tend to bleed together and blur generic distinction so that, for example, a film might be a giallo but the catalyst for its serial killer may be supernatural� (ibid.). In interview, Argento has suggested that the perceived line dividing his �naturalistic� early thrillers and his later supernatural pictures is �an artificial distinction: I don�t see a great difference between them. The realistic pictures are not very realistic, even though they�re about psychopaths rather than witches� (Argento, quoted in ibid.: 75). In the films Argento made after Deep Red, Bondanella suggests, Argento came increasingly to combine the plotting of detective stories with �B movie gore� and baroque studio sets, incorporating violence which �becomes completely gratuitous, irrational, and without any coherent logic�; the cumulative effect, Bondanella says, is �stylish yet chillingly effective� (Bondanella, op cit.: 420).

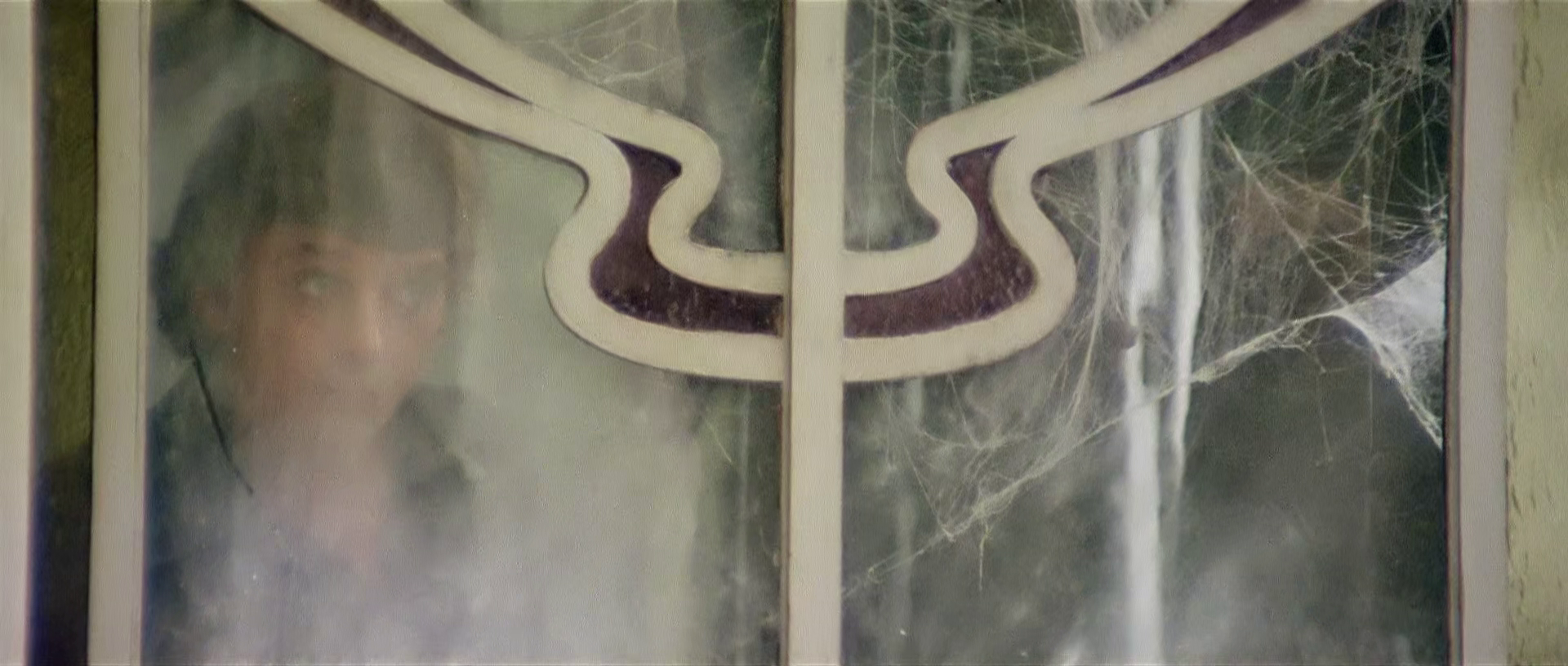

The film contains some subtle hints of the supernatural. Ullman, a psychic, is introduced at a parapsychology conference where she identifies her �power� as having �nothing whatsoever to do with magic, the esoteric or foretelling the future [�.] I can feel thoughts the very instant they�re formed�, she tells the audience. She demonstrates her powers by �reading� a member of the audience but, in doing so, becomes visibly disturbed. She screams. �I can feel� death in this room�, she declares, �A twisted mind sending me thoughts [�.] You have killed and you will kill again [�.] And that house. Death, blood!� (Later, after Ullman�s death, Gianna will dismiss Ullman as being �a kind of magician. She could read people�s thoughts�.) After identifying the child�s lullaby that he hears in his own apartment, Marc is led to Righetti�s book about folklore and the tale of a house where ghostly voices are claimed to act out an act of violence from the past to the accompaniment of a lullaby. When Olga shows Marc to the house, she warns him, �Be careful. There are ghosts in there. Everyone around here says there are�.  Marc�s exploration of the abandoned building is presented via a beautifully shot and edited montage. (In the Twenty-First Century, the iconography within this sequence has found its way into the Youtube videos of urbexers.) One of the standout compositions here sees Marc silhouetted against a window that is partially made of stained glass; the exposure is balanced for the light outside the window, resulting in Marc being surrounded by a gentle halo of light. As Marc explores the building, day turns to night. He discovers the bizarre childish mural depicting the film�s opening murder beneath some peeling plaster. He scrapes some of this away with his hands, and then wanders into the building�s flooded basement to retrieve a fragment of a broken window with which he scrapes away the rest of the plaster covering the mural. Marc�s exploration of the abandoned building is presented via a beautifully shot and edited montage. (In the Twenty-First Century, the iconography within this sequence has found its way into the Youtube videos of urbexers.) One of the standout compositions here sees Marc silhouetted against a window that is partially made of stained glass; the exposure is balanced for the light outside the window, resulting in Marc being surrounded by a gentle halo of light. As Marc explores the building, day turns to night. He discovers the bizarre childish mural depicting the film�s opening murder beneath some peeling plaster. He scrapes some of this away with his hands, and then wanders into the building�s flooded basement to retrieve a fragment of a broken window with which he scrapes away the rest of the plaster covering the mural.

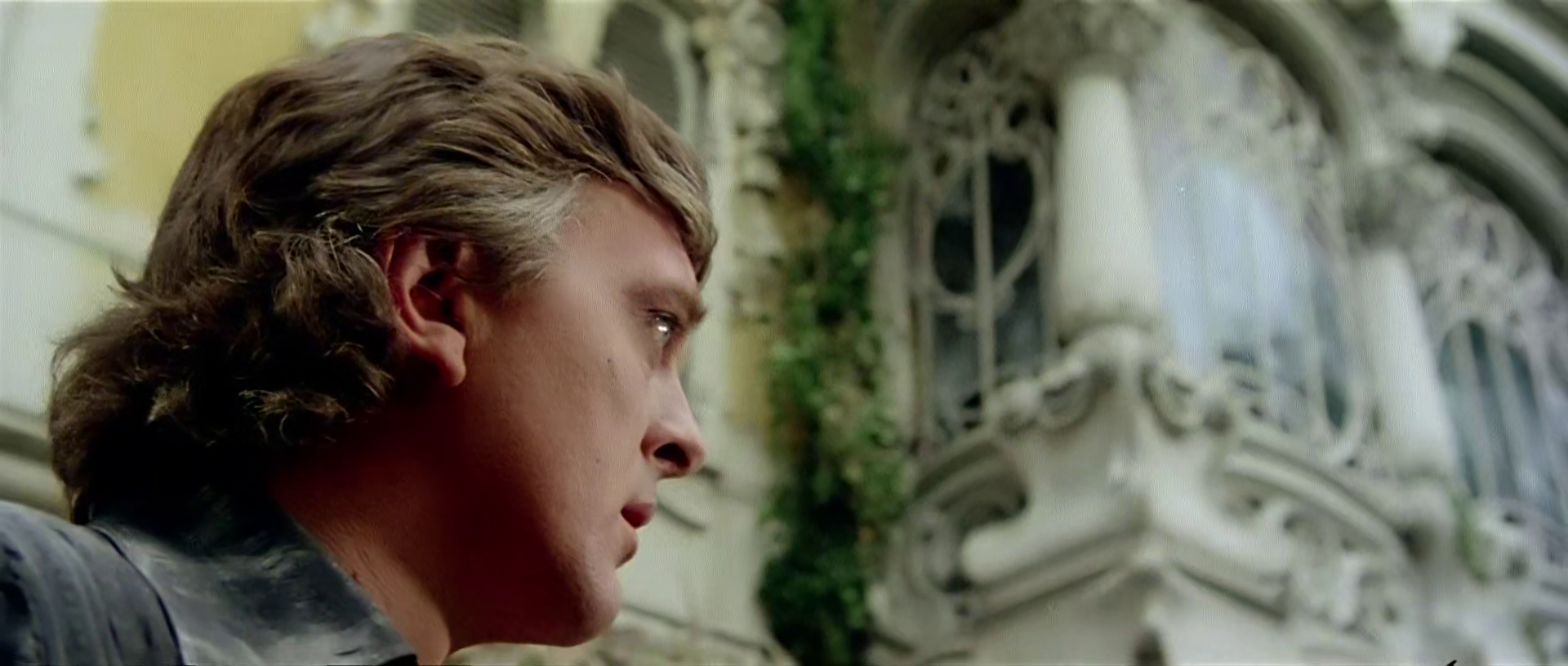

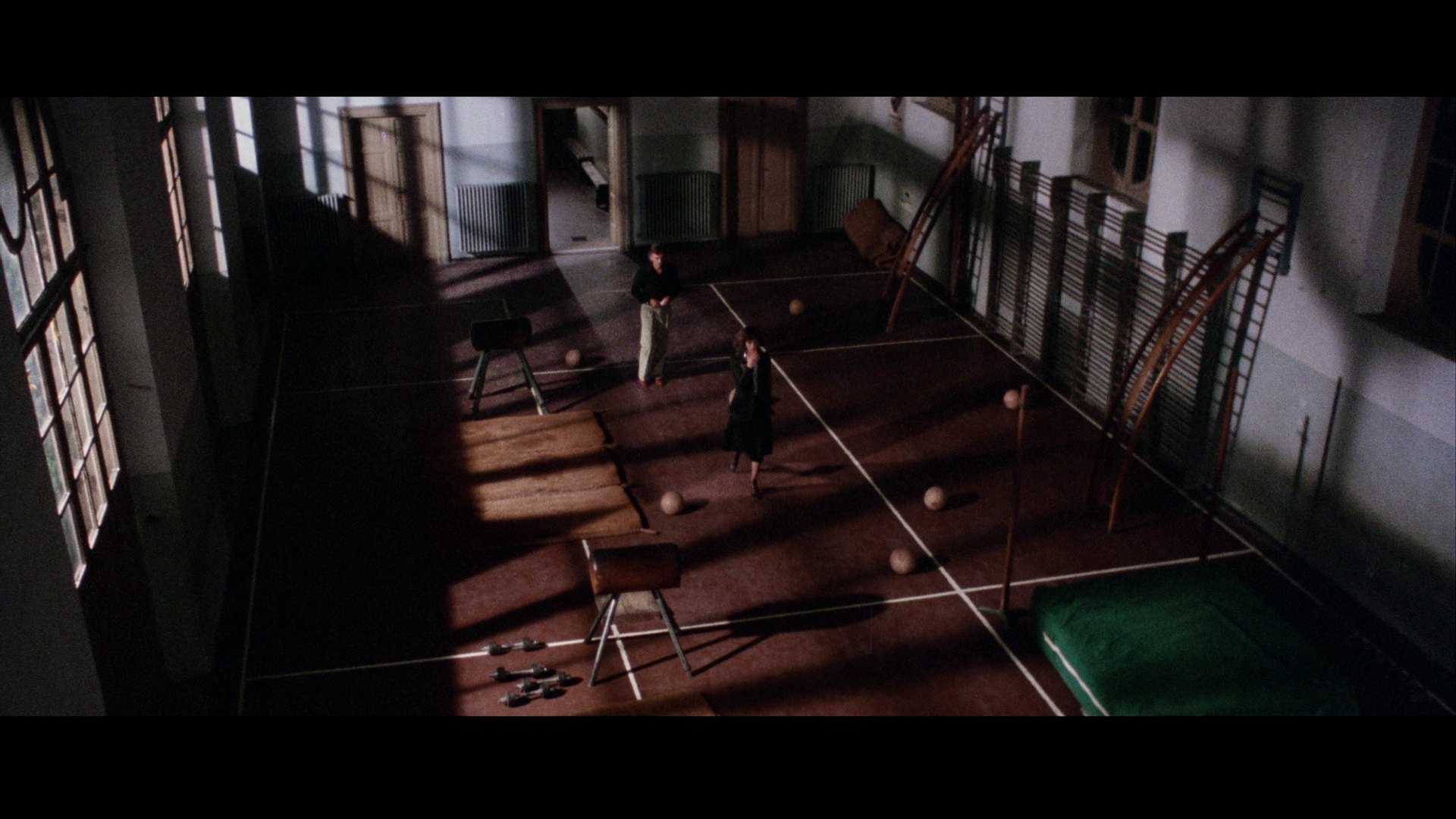

As is the case with a number of Argento�s other films, Deep Red features a protagonist who has a creative background, and who witnesses a crime which he cannot fully comprehend. Like Mark Elliot (Leigh McCloskey) in Inferno, Marc has a background in music, and his profession is repeatedly confused by the film�s antagonist for a more traditionally �masculine� profession. Where the nurse (Veronica Lazar) in Inferno insists on mishearing Mark�s declaration that he is a musicologist (believing him instead to be a toxicologist), in Deep Red no matter how many times Marc tells Marta, Carlo�s mother, that he is a musician, she refers to him as an engineer. The protagonists of Argento�s pictures, Giorgio Bertellini says, are �imperfect and unfocused observer[s]� (Bertellini, 2004: 216). The film juxtaposes Marc�s flawed understanding of events with the point-of-view of the killer, offering us fetishistic close-ups of symbolic objects important to the killer (a doll, glass marbles, a knife) and extreme close-ups of the killer�s eye as they apply makeup to the area surrounding it. Of course, we are also presented with flashbacks to the murder that took place in the past, depicted in the child�s drawings. Bertellini reminds us that at a number of points in the film, scenes �do not reproduce somebody�s actual vision, but memories, or mental images (of a murder), that are imperfectly recollected� (ibid.).  Following the opening depiction of the past murder that haunts the narrative, the film presents us with a scene which features Marc teaching his students. We view Marc from behind a pillar, part of the frame obscured by the pillar�s presence: the view of the scene is partial, as if Marc is being spied on by a voyeur. It�s a filming technique familiar from many contemporaneous Italian thrillers and later American stalk-and-slash pictures: the use of a long shot, often shot with a telephoto lens that flattens perspective, and an object partially obscuring our view in the foreground indicating that we are watching events unfold from the killer�s perspective. However, the mystery narrative hasn�t begun yet, so who precisely is spying on Marc? A similarly oblique point-of-view is presented at the parapsychology conference which immediately follows the scene of Marc teaching his students: we see through the eyes of someone entering the hall where the conference is being held, including a self-referential transition through red curtains, which open like the curtains of a stage to allow the camera (and the character whose perspective we share) to enter the auditorium and take their seat. According to the events that unfold during the conference, the character whose point-of-view we share in this scene would seem to be the killer. After Ullman�s outburst causes the end of the conference and the auditorium empties, Ullman tells Giordano that she knows the identity of the killer. However, their conversation is again filmed in the same type of long shot used to document Marc�s criticisms of his students� playing in the opening scene, the view of Giordano and Ullman partially obscured. The association of this point-of-view shot with the framing of the opening scene featuring Marc may suggest subtly to the viewer that the killer is somehow omniscient. This sense of omniscience is reinforced by the extreme close-ups of the killer�s eye/s which punctuate the narrative. Following the opening depiction of the past murder that haunts the narrative, the film presents us with a scene which features Marc teaching his students. We view Marc from behind a pillar, part of the frame obscured by the pillar�s presence: the view of the scene is partial, as if Marc is being spied on by a voyeur. It�s a filming technique familiar from many contemporaneous Italian thrillers and later American stalk-and-slash pictures: the use of a long shot, often shot with a telephoto lens that flattens perspective, and an object partially obscuring our view in the foreground indicating that we are watching events unfold from the killer�s perspective. However, the mystery narrative hasn�t begun yet, so who precisely is spying on Marc? A similarly oblique point-of-view is presented at the parapsychology conference which immediately follows the scene of Marc teaching his students: we see through the eyes of someone entering the hall where the conference is being held, including a self-referential transition through red curtains, which open like the curtains of a stage to allow the camera (and the character whose perspective we share) to enter the auditorium and take their seat. According to the events that unfold during the conference, the character whose point-of-view we share in this scene would seem to be the killer. After Ullman�s outburst causes the end of the conference and the auditorium empties, Ullman tells Giordano that she knows the identity of the killer. However, their conversation is again filmed in the same type of long shot used to document Marc�s criticisms of his students� playing in the opening scene, the view of Giordano and Ullman partially obscured. The association of this point-of-view shot with the framing of the opening scene featuring Marc may suggest subtly to the viewer that the killer is somehow omniscient. This sense of omniscience is reinforced by the extreme close-ups of the killer�s eye/s which punctuate the narrative.

After his witnessing of Ullman�s murder, Marc becomes convinced that he has seen something, a clue to the crime which he cannot recall precisely. �It�s just an impression, maybe�, he tells Calcabrini. Later, he talks with Carlo, who suggests to Marc that �Maybe you�ve seen something so important that you don�t realise [�.] You know, sometimes what you really see and what you imagine get mixed up in your memory like a cocktail where you can no longer distinguish one flavour from another [�.] You think you�re telling the truth, but in fact you�re only telling your version of the truth. It happens to me all the time�. The infallible perspective of the killer, the sense that s/he is all-seeing and all-knowing, is thus contrasted with Marc�s deeply flawed sense of vision and failure to comprehend what he has witnessed.  Many of Argento�s films confront issues of gender and sexuality, containing characters who challenge the heterosexual norm. From the openly gay private detective played by Jean-Pierre Marielle in Four Flies on Grey Velvet and the unusual chromosomal makeup of the killer in Cat O�Nine Tails, to the use of transgendered actor Eva Robins in Tenebre (Tenebrae, 1982) and the examination of the fluidity of gendered identity in La sindrome di Stendahl (The Stendahl Syndrome, 1996), Argento�s films focus on gender � and especially, the performative aspects of gender identity � in often explicit ways. Both The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Four Flies on Grey Velvet, for example, feature antagonists who are motivated by their cross-gendered identification: in the case of the former film, the killer is a woman who murders because of her identification with the man who attacked her; and in the case of the latter, the killer is a woman whose parents raised her as a boy. Many of Argento�s films confront issues of gender and sexuality, containing characters who challenge the heterosexual norm. From the openly gay private detective played by Jean-Pierre Marielle in Four Flies on Grey Velvet and the unusual chromosomal makeup of the killer in Cat O�Nine Tails, to the use of transgendered actor Eva Robins in Tenebre (Tenebrae, 1982) and the examination of the fluidity of gendered identity in La sindrome di Stendahl (The Stendahl Syndrome, 1996), Argento�s films focus on gender � and especially, the performative aspects of gender identity � in often explicit ways. Both The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Four Flies on Grey Velvet, for example, feature antagonists who are motivated by their cross-gendered identification: in the case of the former film, the killer is a woman who murders because of her identification with the man who attacked her; and in the case of the latter, the killer is a woman whose parents raised her as a boy.

Like many of Argento�s films, Deep Red foregrounds themes of gender and gendered identity. Marc is challenged by Gianna�s assertive manner and her tendency to adopt stereotypically masculine habits like smoking cigarillos. Gianna�s courage is set against Marc�s cowardice, and when Gianna teases Marc for being nervous about the publication of his photograph in the newspaper and its potential for attracting the attention of Ullman�s killer, he hides behind the stereotypes associated with his career: �It�s in my nature. It�s my artistic temperament�, he says. The couple talk about gender equality, and Marc falls back on gender stereotypes: �Oh, don�t start with all that woman stuff�, he declares, �It is a fundamental fact. Men are different from women. Women are weaker� Well, they�re gentler�. In response to this, Gianna challenges Marc to a bout of arm wrestling. She wins. After Marc discovers that the killer is stalking him in Marc�s own apartment, Marc saves himself by calling Gianna; and it is Gianna who drags Marc out of the burning building towards the climax of the picture. Following his discovery of Righetti�s body, Marc jokingly subverts gender roles in a conversation with Gianna, telling her �Let�s be honest. You women have brute force. You beat me at arm wrestling. But us men have the monopoly on intelligence�. The �sparring�, flirtatious interplay between Marc and Gianna, downplayed in the shorter international cut of the film, seemingly deliberately recalls the tough-talking women of Howard Hawks� films (such as Lauren Bacall�s Slim in To Have and Have Not, 1944); and in particular, the gender role reversal that Deep Red hints at through the interactions between Marc and Gianna is reminiscent of the gender reversal that takes place in Hawks� Bringing Up Baby (1938), in which David Huxley (Cary Grant) assumes a largely passive position whilst Susan (Katherine Hepburn) adopts a more traditionally �masculine� role.  Alongside the accusations of misogyny that dog much of Argento�s work, Deep Red has been questioned for its representation of sexuality: in terms of the film�s depiction of the self-loathing Carlo, Shipka has connected Deep Red with a spate of Italian films of the 1970s that �depicted gays as victims who were made to suffer because of their [sexual] orientation, or as perpetrators of crime because of their �obvious� psychosis� (Shipka, op cit.: 88). Introduced as a drunk who jokes about placing little value on his own life, Marc�s friend Carlo is revealed to be gay when Marc visits Carlo�s home and Carlo�s mother Marta tells Marc that her son is with his friend Ricci. (In this scene, Marc is positioned almost as a child who is visiting his schoolmate�s house to ask if they can come out to play.) Marta gives Marc the address, and Marc visits it; knocking on the door, Marc is mildly surprised when it is answered by Ricci, revealed to be a male transvestite (who, to add to the gender confusion, is actually played by an actress, Geraldine Hooper). The revelation of Carlo�s sexuality doesn�t affect Marc, who views his friend with the same sympathy he held for him prior to discovering that Carlo is gay. However, Carlo is riddled with self-hatred. �Good old Carlo�, he asserts drunkenly when Marc enters the apartment, �He�s not only drunk but a faggot as well�. Alongside the accusations of misogyny that dog much of Argento�s work, Deep Red has been questioned for its representation of sexuality: in terms of the film�s depiction of the self-loathing Carlo, Shipka has connected Deep Red with a spate of Italian films of the 1970s that �depicted gays as victims who were made to suffer because of their [sexual] orientation, or as perpetrators of crime because of their �obvious� psychosis� (Shipka, op cit.: 88). Introduced as a drunk who jokes about placing little value on his own life, Marc�s friend Carlo is revealed to be gay when Marc visits Carlo�s home and Carlo�s mother Marta tells Marc that her son is with his friend Ricci. (In this scene, Marc is positioned almost as a child who is visiting his schoolmate�s house to ask if they can come out to play.) Marta gives Marc the address, and Marc visits it; knocking on the door, Marc is mildly surprised when it is answered by Ricci, revealed to be a male transvestite (who, to add to the gender confusion, is actually played by an actress, Geraldine Hooper). The revelation of Carlo�s sexuality doesn�t affect Marc, who views his friend with the same sympathy he held for him prior to discovering that Carlo is gay. However, Carlo is riddled with self-hatred. �Good old Carlo�, he asserts drunkenly when Marc enters the apartment, �He�s not only drunk but a faggot as well�.

Marc�s discovery that the �haunted� house was Carlo�s childhood home and that the graphic drawing in the school archives is signed by Carlo highlights for Marc the traumatic event in Carlo�s childhood, and points to Carlo as being the killer � connecting metonymically Carlo�s sexuality with his �deviance� and further compounding the suggestions of a �broken� childhood, or the shattering of childhood innocence, that (using Edvard Munch-esque psychological symbolism) have to this point been contained within the film�s mise-en-sc�ne � for example, the iconography of the broken doll). This is compounded by the fact that Carlo still lives with his mother, recalling another famous mother-son pairing � that which exists between Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and his mother in Alfred Hitchcock�s Psycho (1960). However, this is undermined when it is revealed that Carlo isn�t the murderer: that he has simply been used as a �patsy� of sorts, defending the real murderer. In this sense, the film plays to the negative stereotypes that are accumulated around Carlo�s sexuality before subverting them dramatically. Throughout the film, Argento casts suspicion on a number of characters, including both Carlo and Gianni. Danny Shipka has suggested that in the world depicted within Deep Red �mother, lover, brother or child could be a possible murderer� (Shipka, op cit.: 95). By constantly casting suspicion upon the characters in the film, Argento maintains an �emotional distance� between the viewer and these characters (ibid.). It�s a picture in which the characters� various traits correspond to those outlined in �Freud�s dictionary of neurosis�: the characters are predominantly �motivated by self-loathing, �victims of their own self-esteem� (ibid.).  Through the relationship between Marc and Carlo, the film explores the politics of music. As the film begins, Marc is shown teaching his students. He interrupts their performance to tell them sharply that their playing is �too formal� and �too precise�; as if offering a statement of intent for the film itself, Marc reminds the musicians that �It [their performance] should be more trashy. Remember that this sort of jazz came out of the brothels�. Several times, the film directly contrasts Marc and Carlo, two pianists who live very different lifestyles; and the irony is that playing piano for the patrons of the Blue Bar, Carlo lives the �trashy�, proletarian life that Marc praises to his students. Marc shows deep concern for his friend Carlo. When we first see Carlo, he is in the piazza outside Marc�s apartment building, and near the Blue Bar. (The iconography of the Blue Bar deliberately recalls the imagery within Edward Hopper�s famous 1942 painting �Nighthawks�.) Carlo is drunk; Marc warns him, �you go on the way you are, you won�t last very long�. �Who says I want to last?�, Carlo responds before adding to Marc, �The difference between you and me is purely political. You see, we both play good piano, but I�m the proletariat of the keyboard and you�re the bourgeois. You play for art and enjoy it; I play for survival. It�s not the same thing�. Following the death of Ullman, Marc faces prejudice about his profession from Calcabrini (Eros Pagni), the detective who is investigating the murder. �So you�re a foreigner, then?�, Calcabrini asks Marc, �What are you doing in Italy?� Marc tells Calcabrini that he teaches jazz at the conservatory. �So, in that case, you don�t have a job, then?�, Calcabrini asks. �Playing an instrument isn�t a job?�, Marc responds angrily, �What is it, a joke?� Through the relationship between Marc and Carlo, the film explores the politics of music. As the film begins, Marc is shown teaching his students. He interrupts their performance to tell them sharply that their playing is �too formal� and �too precise�; as if offering a statement of intent for the film itself, Marc reminds the musicians that �It [their performance] should be more trashy. Remember that this sort of jazz came out of the brothels�. Several times, the film directly contrasts Marc and Carlo, two pianists who live very different lifestyles; and the irony is that playing piano for the patrons of the Blue Bar, Carlo lives the �trashy�, proletarian life that Marc praises to his students. Marc shows deep concern for his friend Carlo. When we first see Carlo, he is in the piazza outside Marc�s apartment building, and near the Blue Bar. (The iconography of the Blue Bar deliberately recalls the imagery within Edward Hopper�s famous 1942 painting �Nighthawks�.) Carlo is drunk; Marc warns him, �you go on the way you are, you won�t last very long�. �Who says I want to last?�, Carlo responds before adding to Marc, �The difference between you and me is purely political. You see, we both play good piano, but I�m the proletariat of the keyboard and you�re the bourgeois. You play for art and enjoy it; I play for survival. It�s not the same thing�. Following the death of Ullman, Marc faces prejudice about his profession from Calcabrini (Eros Pagni), the detective who is investigating the murder. �So you�re a foreigner, then?�, Calcabrini asks Marc, �What are you doing in Italy?� Marc tells Calcabrini that he teaches jazz at the conservatory. �So, in that case, you don�t have a job, then?�, Calcabrini asks. �Playing an instrument isn�t a job?�, Marc responds angrily, �What is it, a joke?�

Like many of Argento�s films, Deep Red is a deeply divisive picture. John Kenneth Muir has suggested that the film offers �a loosely connected tapestry of incredible horror imagery, punctuated by moments of terrible plotting, atrocious dialogue and confusing scenarios� (Muir, 2002: 390). Consequently, Muir argues, Argento forces the viewer to choose between intellectual and visceral pleasures: �which is more important, believability or the �gut�� (ibid.). The intellectual, Muir suggests, �would surely laugh at Argento�s failed attempts at psychological depth, while, if tuned into his own feelings, the self-same intellectual would acknowledge deep discomfort at the action on screen� (ibid.). The dense web of references Argento builds towards the cinema of the past (of which the tip of the proverbial iceberg is the casting of Hemmings in allusion to his role in Antonioni�s Blow-Up) led to the perception of the director as �a fanatically cinephile and thus disengaged and solipsistic filmmaker� whose work offers �a stylistic exercise, unworthy of in-depth analysis� and �lack[s] cultural [�] and artistic consistency� (Bertellini, 2004: 213). Argento is a filmmaker who, for his strongest critics, is �lost in his own nightmarish obsessions� (ibid.). (Similar criticisms have, of course, since been leveled against Quentin Tarantino, whose films have a similar level of referentiality to Argento�s.) On the other hand, for Bertellini, Argento is �an anti-Establishment philosopher of cinematic vision� for whom �the visual experience is intrinsically tied to violence and pleasure, danger and addiction, not to a dispassionate conduit to the truth� (Bertellini, op cit.: 216). Like many of Argento�s films, Deep Red is a deeply divisive picture. John Kenneth Muir has suggested that the film offers �a loosely connected tapestry of incredible horror imagery, punctuated by moments of terrible plotting, atrocious dialogue and confusing scenarios� (Muir, 2002: 390). Consequently, Muir argues, Argento forces the viewer to choose between intellectual and visceral pleasures: �which is more important, believability or the �gut�� (ibid.). The intellectual, Muir suggests, �would surely laugh at Argento�s failed attempts at psychological depth, while, if tuned into his own feelings, the self-same intellectual would acknowledge deep discomfort at the action on screen� (ibid.). The dense web of references Argento builds towards the cinema of the past (of which the tip of the proverbial iceberg is the casting of Hemmings in allusion to his role in Antonioni�s Blow-Up) led to the perception of the director as �a fanatically cinephile and thus disengaged and solipsistic filmmaker� whose work offers �a stylistic exercise, unworthy of in-depth analysis� and �lack[s] cultural [�] and artistic consistency� (Bertellini, 2004: 213). Argento is a filmmaker who, for his strongest critics, is �lost in his own nightmarish obsessions� (ibid.). (Similar criticisms have, of course, since been leveled against Quentin Tarantino, whose films have a similar level of referentiality to Argento�s.) On the other hand, for Bertellini, Argento is �an anti-Establishment philosopher of cinematic vision� for whom �the visual experience is intrinsically tied to violence and pleasure, danger and addiction, not to a dispassionate conduit to the truth� (Bertellini, op cit.: 216).

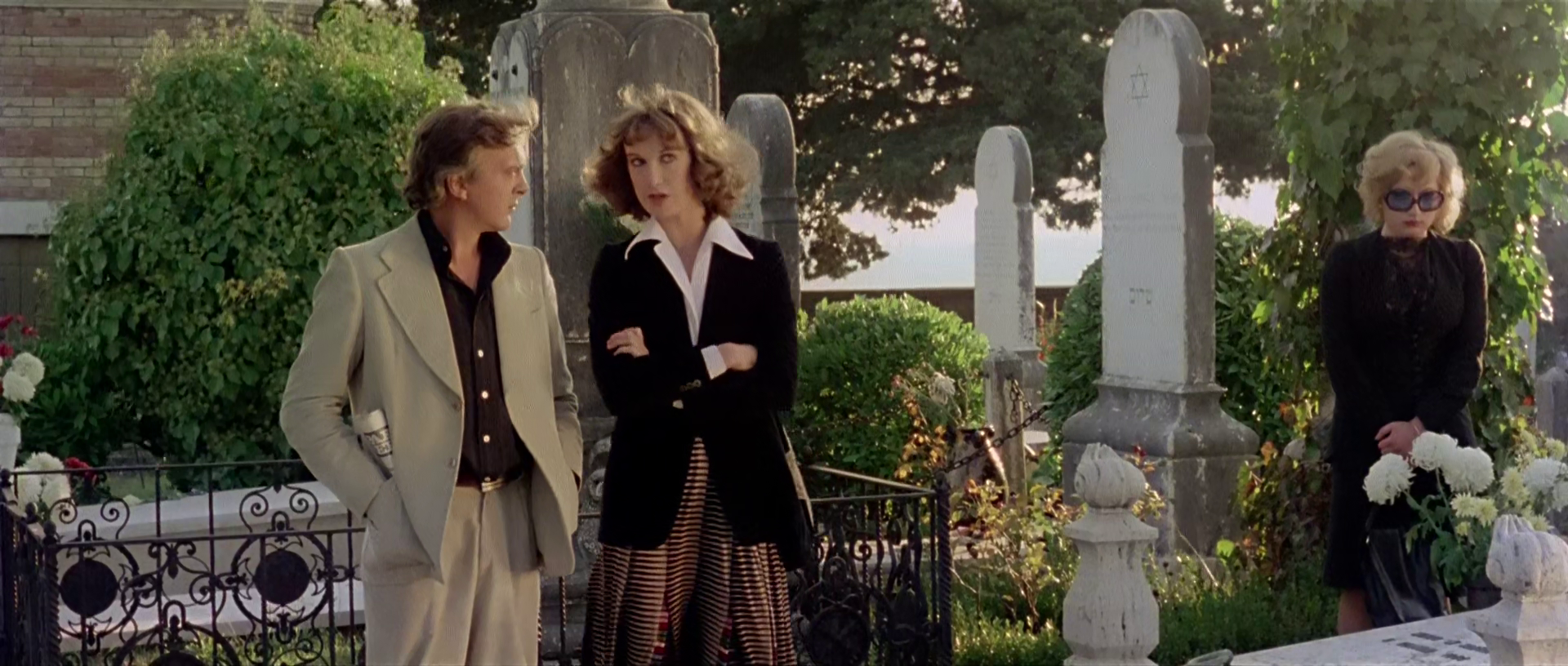

This release contains both the domestic Italian cut of Deep Red, running 127:13 mins, and the shorter English-language export/�international� cut of the film, running 104:53 mins. The export cut shortens some of the violence of the Italian cut and also abbreviates a number of shots without dialogue. It omits some moments of dialogue too, including the following: (1) Marc telling his students about the origins of jazz in music played in bordellos; (2) Some dialogue during the parapsychology conference; (3) Part of Marc�s conversation with Carlo in the piazza, prior to Marc witnessing Ullman�s murder; (4) Some of the conversations involving the police at the scene of Ullman�s murder; (5) The police attempting to usher Gianni away from the scene of Ullman�s murder; (6) Outside the apartment building, the police leave and Marc and Carlo resume their conversation; (7) Marc and Gianni converse in the cemetery during Ullman�s funeral, with Gianni telling Marc that she is single; (8) Marc asks for Carlo at the Blue Bar; (9) Gianni asks Marc if he finds her unattractive; (10) Carlo�s lover Ricci tells Marc about Carlo�s drinking; (11) The bartender at the Blue Bar comments on how good Carlo�s piano playing is; (12) Some of Giordano�s comments to Marc about the killer; (13) After discovering Righetti�s corpse, Marc discusses his options with Gianni; (14) A comic scene at the police station, and part of a telephone conversation between Marc and Gianni; (15) Marc and Gianni regroup after Giordano�s death, and Marc talks of the killer �know[ing] every move� before suggesting fleeing the country. There�s an anomaly in the export cut that�s presented on Arrow�s BD. Arrow painstakingly reassembled the shorter cut of the picture from the 4k restoration on which the presentation of the longer Italian version is based, to ensure that the two cuts of the film are equal in quality. Arrow�s version of the shorter cut contains one or perhaps two frames from a shot of a man on a bicycle carrying the Italian flag; it�s a shot which isn�t meant to appear in the shorter export cut of the film. It�s a very, very brief error and only incredibly observant viewers will notice it.

Video

Arrow�s presentation of the film is based on a new 4k restoration conducted in 2014 by Cineteca Nazionale. This restoration is based on scan of the original negative, with some frames that were missing from the 2-perf negative replaced with frames from a vintage interpositive. The Italian domestic cut and the shorter English-language export cut are housed on separate Blu-ray discs. The longer Italian cut takes up approximately 37Gb of space on its disc, and the shorter export cut fills approximately 22Gb of space on the disc allocated to it. Arrow�s presentation of the film is based on a new 4k restoration conducted in 2014 by Cineteca Nazionale. This restoration is based on scan of the original negative, with some frames that were missing from the 2-perf negative replaced with frames from a vintage interpositive. The Italian domestic cut and the shorter English-language export cut are housed on separate Blu-ray discs. The longer Italian cut takes up approximately 37Gb of space on its disc, and the shorter export cut fills approximately 22Gb of space on the disc allocated to it.

Deep Red was shot in Techniscope, the cost-saving 2-perf format that achieved an aspect ratio of 2.39:1 without the use of anamorphic lenses. Techniscope decreased production costs by effectively halving the amount of film stock needed to shoot a film by halving the amount of space on the negative taken up by each frame, but this resulted in Techniscope pictures having a slightly different �texture� (in still photography terms, comparisons could be made with the carte-de-visite or the popularity of half-frame cameras like the Olympus Pen F during the 1960s). However, it�s been said that this was balanced out by the lab costs, which for Techniscope pictures were said to be more expensive than for a film shot in a conventional 4-perf format. Release prints of films shot in Techniscope would be made by antropomorphisising the image and doubling the size of each frame; this would result in a grain structure that was noticeably more dense than that of a film shot in a 4-perf format. (Anyone who�s used a half-frame 35mm camera will recognise the principle and the effect this has on the structure of an image.) During the 1960s, Techniscope pictures were blown up using the dye transfer processes employed by Technicolor Italia, and with these processes it was possible to skip the dupe negative step and thus �save� a generation; the result was an image with a finer grain structure and deeper blacks (characteristics of films produced using dye transfer processes generally, not just those shot in Techniscope). In the 1970s, for economic reasons dye transfer printing for films shot in Techniscope was replaced with the standard Kodak colour printing process, which necessitated the production of a dupe negative (and an additional �generation� for the material). This resulted in a more coarse grain structure to Techniscope films released in the 1970s and beyond.  Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances. Additionally, owing to the reduction of the size of each frame, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and affected their field of view too: with Techniscope, an 18mm lens would provide a roughly similar field of view to a 35mm lens on a 4-perf production, and shooting at f2.8 on a Techniscope production would achieve the same depth of field as shooting at f5.6 on a picture shot in a 4-perf format. Consequently, Techniscope productions evidence an increased depth of field and sense of depth to the image, something which can be seen in some of the more famous examples of pictures shot in the format (for example, Sergio Leone�s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964). Freed from the need to use anamorphic lenses, cinematographers using the Techniscope process were able to employ technically superior spherical lenses with shorter focal lengths and shorter hyperfocal distances. Additionally, owing to the reduction of the size of each frame, the Techniscope format shortened the hyperfocal distances of prime lenses and affected their field of view too: with Techniscope, an 18mm lens would provide a roughly similar field of view to a 35mm lens on a 4-perf production, and shooting at f2.8 on a Techniscope production would achieve the same depth of field as shooting at f5.6 on a picture shot in a 4-perf format. Consequently, Techniscope productions evidence an increased depth of field and sense of depth to the image, something which can be seen in some of the more famous examples of pictures shot in the format (for example, Sergio Leone�s A Fistful of Dollars, 1964).

By being based on a scan of the film�s negative, this presentation of Deep Red bypasses the 4-perf blow-up stage, with the result that like Arrow�s recent HD release of Massimo Dallamano�s What Have You Done to Solange?, Deep Red seems to share more the characteristics of a Techniscope print produced by Technicolor Italia�s dye transfer processes than the release prints of many 1970s Techniscope productions. The presentation has a finer, tighter grain structure than some print/IP-sourced presentations of contemporaneous Techniscope pictures, and evidences some rich, deep blacks. (The rich blacks in this new presentation from Arrow, and the contrast levels generally, are one of the more immediately noticeable improvements that this presentation offers over Deep Red�s previous Blu-ray releases from Blue Underground in the US and Arrow in the UK.) Throughout the film, there�s heavy use of very short focal lengths, with many scenes evidencing the characteristics associated with the use of wide-angle lenses (such as barrel distortion) and incredible depth of field. A recurring visual leitmotif within the film is a shot of characters framed in a doorway, or at the end of the corridor, suggesting that the characters are trapped; this type of composition appears also when Marc is seen through the viewfinder of Gianni�s camera, and in an eerily similar shot in which his torchlight illuminates the dessicated corpse in the hidden room of the house. (As a sidenote, watching the film in widescreen for the first time via its DVD release around 2000 was a revelation in comparison with my previous home video viewings, which had been via the heavily cropped VHS release from Redemption; the compositions in the picture are stunning in their use of the widescreen frame.) This is communicated superbly in this presentation, which displays a highly impressive level of detail and depth in comparison with Deep Red�s previous home video presentations. (Some screen grabs comparing Arrow�s new HD presentation with the Blue Underground Blu-ray release are included at the bottom of this review.) Colours are also noticeably different, with skin tones in Arrow�s new presentation looking more authentic and the film having a slightly cooler palette overall. Finally, an excellent encode carries the new presentation very well, retaining the structure of 35mm film and offering an organic, film-like viewing experience.

Audio

The longer Italian cut presents the viewer with the option of watching a film with three different lossless tracks: (1) the Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track; (2) a newer Italian DTS-HD MA 5.1 remix; (2) an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track sourced form the English-language export cut, with the footage excised from the shorter export version presented in Italian with optional English subtitles. Alongside these partial subtitles for the English/Italian audio track, full optional English subtitles are included for the Italian audio options. All three tracks are in good shape, displaying a strong sense of range � from the bassy notes of the film�s pounding main titles music to the more shrill sounds of a violin that punctuate the score. Given that like many Italian productions of the era, the film was shot with post-synch sound, and picture features an international cast, both the English and Italian versions are technically dubbed. The English track benefits from Hemmings� own voice; and as English language dubs go, it�s a good one, with the secondary characters being dubbed convincingly. The 5.1 remix is the same one which has appeared on the film�s previous digital home video releases, and the sound separation on this track sounds artificial; purists will want to stick with one or the other (or both � as it�s a film worth watching in both English and Italian, just for the sake of comparison) of the mono tracks. The longer Italian cut presents the viewer with the option of watching a film with three different lossless tracks: (1) the Italian DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track; (2) a newer Italian DTS-HD MA 5.1 remix; (2) an English DTS-HD MA 1.0 mono track sourced form the English-language export cut, with the footage excised from the shorter export version presented in Italian with optional English subtitles. Alongside these partial subtitles for the English/Italian audio track, full optional English subtitles are included for the Italian audio options. All three tracks are in good shape, displaying a strong sense of range � from the bassy notes of the film�s pounding main titles music to the more shrill sounds of a violin that punctuate the score. Given that like many Italian productions of the era, the film was shot with post-synch sound, and picture features an international cast, both the English and Italian versions are technically dubbed. The English track benefits from Hemmings� own voice; and as English language dubs go, it�s a good one, with the secondary characters being dubbed convincingly. The 5.1 remix is the same one which has appeared on the film�s previous digital home video releases, and the sound separation on this track sounds artificial; purists will want to stick with one or the other (or both � as it�s a film worth watching in both English and Italian, just for the sake of comparison) of the mono tracks.

The shorter export cut features the same English DTS-HD 1.0 mono track, but obviously minus the inserts from the Italian version of the picture. This shorter cut is also accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:  DISC ONE (Blu-ray): DISC ONE (Blu-ray):

* The film (longer Italian domestic version) (127:13) - an optional introduction by Claudio Simonetti (0:23). - Audio commentary with Thomas Rostock. This commentary has appeared on Arrow�s previous Blu-ray release of the film. Rostock, a filmmaker himself, offers a strong discussion of Argento�s technique. He sometimes falls into the trap of describing what�s taking place on screen, but it�s a predominantly fascinating track in which Rostock makes a strong attempt to contextualises Argento�s work through references to filmmakers such as Fritz Lang and Hitchcock. - �Profondo Giallo� (32:57). This is a new video essay by Argento enthusiast Michael Mackenzie, who situates the picture within the context of Argento�s career and discusses Argento�s impact on the thrilling. Mackenzie is deeply enthusiastic about Deep Red and Argento�s thrilling films more generally. Perhaps because of this, he arguably overstates Argento�s importance in defining the thrilling all�italiana and, flowing from this, the notion of Deep Red as the �giallo to end all gialli�; but he explores the film�s themes in detail and with the help of some snazzily-edited footage from the film and its trailers. There�s detailed discussion of the violence in the film and the picture�s use of music, and an examination of Argento�s representation of gender. It�s a very good piece that new viewers will find informative and illuminating. Alongside this are some vintage video pieces, which had appeared on Arrow�s previous Blu-ray release:  - �Rosso Recollections (12:26). This interview with Argento sees the filmmaker reflecting on Deep Red. Argento is typically quiet and reserved here, sometimes offering very pithy, gnomic responses to questions. He talks about how the film came to be produced and discusses some of its salient features (eg, engaging with the suggestion that has been made by some critics that Hemmings� character may be gay). The interview ends with mention of David Gordon Green�s planned remake of Suspiria � which seven years after the interview was conducted, thank Heaven, hasn�t happened yet. This interview is in Italian with burnt-in English subtitles. - �Rosso Recollections (12:26). This interview with Argento sees the filmmaker reflecting on Deep Red. Argento is typically quiet and reserved here, sometimes offering very pithy, gnomic responses to questions. He talks about how the film came to be produced and discusses some of its salient features (eg, engaging with the suggestion that has been made by some critics that Hemmings� character may be gay). The interview ends with mention of David Gordon Green�s planned remake of Suspiria � which seven years after the interview was conducted, thank Heaven, hasn�t happened yet. This interview is in Italian with burnt-in English subtitles.

- �The Lady in Red� (18:47). Here, Daria Nicolodi reflects on the film. She praises the picture as �wonderful and mercurial� and reflects on her romantic relationship with Argento. Nicolodi talks about the pictures Argento made prior to Deep Red and explains how she came to be cast in the film. She discusses her performance in the picture and her character�s �masculine gestures�. This interview is also in Italian with burnt-in English subtitles. - �Music to Murder For!� (14:06). Claudio Simonetti discusses the film�s music. (There�s an odd typographical error onscreen at one point which identifies the band Goblin as the �Golblins�.) He talks about the early years of Goblin and the history of the band, and he contrasts the ways in which film scores were written and performed in the 1970s with how they are produced today. This interview is in English. - �Profondo Rosso: From Celluloid to Shop� (14:30). Argento�s friend and collaborator Luigi Cozzi offers the viewer a glimpse into the Profondo Rosso shop in Rome. Cozzi discusses his relationship with Argento before taking the crew on a tour of the �museum� within the premises, showing them some of the artifacts from both Argento�s and Cozzi�s films that are on display there. The interview is in English and Italian with burnt-in English subtitles. - the film�s Italian trailer (1:49). DISC TWO (Blu-ray): * The film (shorter English-language export version) (104:53) - the film�s English trailer (2:43). Retail versions of this release also come with a third disc: a CD containing the film�s soundtrack by Goblin.

Overall

Deep Red is a superb example of the thrilling all�italiana. The film has some very enthusiastic supporters, and it�s often cited as one of the defining pictures of the thrilling form of the 1970s. Identifying the film as such has its problems, as suggested above, and although the strongest voices these days tend to be those of the film�s fans, the picture is also deeply divisive and inspires in some viewers a very strong negative reaction. The longer Italian domestic version and the shorter English-language export cut have very different qualities, with the former offering a very rich and expansive canvas on which Argento paints his picture in the deepest of reds, whilst the latter offers a far more conventionally paced thriller. Both cuts of the film have their fans, with some preferring the longer Italian cut and others preferring the shorter export version; yet others might find themselves oscillating between the two cuts. Regardless, it�s immensely pleasing that Arrow have included both cuts of the film here � and not only that, they have reconstructed the shorter English cut from the 4k restoration of the longer Italian version. (There�s one brief anomaly in Arrow�s reconstruction of the shorter cut, outlined above, but it�s a blink-and-you�ll-miss-it moment.) The presentation of the film on this release is superb, easily eclipsing the previous Blu-ray releases. Whilst the bulk of the contextual material will be familiar to those who bought Arrow�s previous Blu-ray release, the new video essay by Michael Mackenzie is very good, especially for a first-time viewer. In all, this is a superb release that should please those (including myself) who found the film�s previous Blu-ray incarnations disappointing. Deep Red is a superb example of the thrilling all�italiana. The film has some very enthusiastic supporters, and it�s often cited as one of the defining pictures of the thrilling form of the 1970s. Identifying the film as such has its problems, as suggested above, and although the strongest voices these days tend to be those of the film�s fans, the picture is also deeply divisive and inspires in some viewers a very strong negative reaction. The longer Italian domestic version and the shorter English-language export cut have very different qualities, with the former offering a very rich and expansive canvas on which Argento paints his picture in the deepest of reds, whilst the latter offers a far more conventionally paced thriller. Both cuts of the film have their fans, with some preferring the longer Italian cut and others preferring the shorter export version; yet others might find themselves oscillating between the two cuts. Regardless, it�s immensely pleasing that Arrow have included both cuts of the film here � and not only that, they have reconstructed the shorter English cut from the 4k restoration of the longer Italian version. (There�s one brief anomaly in Arrow�s reconstruction of the shorter cut, outlined above, but it�s a blink-and-you�ll-miss-it moment.) The presentation of the film on this release is superb, easily eclipsing the previous Blu-ray releases. Whilst the bulk of the contextual material will be familiar to those who bought Arrow�s previous Blu-ray release, the new video essay by Michael Mackenzie is very good, especially for a first-time viewer. In all, this is a superb release that should please those (including myself) who found the film�s previous Blu-ray incarnations disappointing.

Bibliography: Bertellini, Giorgio, 2004: �Profondo Rosso/Deep Red�. In: Bertellini, Giorgio (ed), 2004: The Cinema of Italy. London: Wallflower Press: 213-24 Bondanella, Peter, 2009: A History of Italian Cinema. London: Continuum International Publishing Dixon, Wheeler Winston, 2010: A History of Horror. Rutgers University Press Koven, Mikel J, 2006: La Dolce Morte: Vernacular Cinema and the Italian Giallo Film. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Marlow-Mann, Alex, 2011: �Black Sabbath�. In: Bayman, Louis, 2011: Directory of World Cinema: Italy. Bristol: Intellect Books Met, Philippe, 2006: ��Knowing Too Much� About Hitchcock: The Genesis of the Italian Giallo�. In: Boyd, David & Palmer, R Barton (eds), 2006: After Hitchcock: Influence, Imitation, and Intertextuality. University of Texas Press: 195-214 Moliterno, Gino, 2009: The A to Z of Italian Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Muir, John Kenneth, 2002: Horror Films of the 1970s. London: McFarland Nerenberg, Ellen, 2012: Murder Made in Italy: Homicide, Media, and Contemporary Italian Culture. Indiana University Press Shipka, Danny, 2011: Perverse Titillation: The Exploitation Cinema of Italy, Spain and France, 1960-1980. London: McFarland Screen grabs: Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration:

Blue Underground�s previous Blu-ray release:

Arrow�s new 4k restoration: