|

|

5 Dolls for an August Moon AKA 5 Bambole per la luna d'agosto

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (9th February 2016). |

|

The Film

Cinque bambole per la luna d’agosto AKA Five Dolls for an August Moon (Mario Bava, 1970) Cinque bambole per la luna d’agosto AKA Five Dolls for an August Moon (Mario Bava, 1970)

Having consolidated (if not defined) the popular conception of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) with the 1964 picture Sei donne per l’assassino (‘Six Women for the Killer’, more commonly known in English-speaking territories as Blood and Black Lace), Mario Bava left the thrilling for a number of years before returning with a vengeance in the year 1970. Blood and Black Lace became an icon of the ‘bodycount’ approach within the thrilling all’italiana: a killer, clad in black, picks off a number of victims (the ‘six women for the killer’ of the Italian title), with the focus being on the murders as setpieces that punctuate the narrative. The fearsome reputation of Blood and Black Lace, and its bravura approach to its material, arguably overshadowed many later Italian thrillers and led to the reductive perception of the thrilling all’italiana as being solely about black-gloved killers and a bodycount approach to narrative structure. (This perception was consolidated by Dario Argento’s Italian thrillers from L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo/The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, 1970, to Profondo rosso/Deep Red, 1975.) However, the thrilling all’italiana is a remarkably diverse subgenre or style of filmmaking: although there are some elements which recur throughout many of the Italian-produced thrillers of the 1960s and 1970s, in terms of narrative content, on close inspection the pictures often defy easy classification or ‘pigeon-holing’.  Cinque bambole per la luna d’agosto (Five Dolls for an August Moon, 1970) was shot and released at around the same time as Mario Bava’s other examples of the thrilling all’italiana, Il rosso segno della follia (Hatchet for the Honeymoon, 1970) and Reazione a catena (A Bay of Blood/Blood Bath, 1971). Those three pictures, all directed by Bava (though Five Dolls for an August Moon was the only one of the three films on which Bava didn’t also act as cinematographer), showcase the diversity of the thrilling all’italiana. In stark contrast with the ‘bodycount’/whodunit approach of Blood and Black Lace, Hatchet for a Honeymoon is a dry, subversive thriller whose narrative is focalised through the point-of-view of the film’s murderer, John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth). Harrington is a respectable businessman who lives a double life as a cold blooded killer; through the presentation of the narrative from his perspective, we come to understand his crimes, in the manner of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Unlike Blood and Black Lace, Hatchet for a Honeymoon is remarkable restrained, with very little in the way of overt violence. By contrast, A Bay of Blood is very graphic in its depiction of violence, and retains the whodunit plotting of Blood and Black Lace, the identity of the murderer/s remaining a mystery until the film’s climax. Sandwiched in between Hatchet for a Honeymoon and Bay of Blood, Five Dolls for an August Moon takes the whodunit structure of Blood and Black Lace and A Bay of Blood, marrying it with the relatively bloodless aesthetic of Hatchet for a Honeymoon. Despite their differences in terms of narrative and violence, these three films within Bava’s body of work share a common theme: a depiction of the powerful – especially powerful men who are motivated by greed – as corrupt, and the notion of greed and self-interest as the key motivators behind acts of violence. Cinque bambole per la luna d’agosto (Five Dolls for an August Moon, 1970) was shot and released at around the same time as Mario Bava’s other examples of the thrilling all’italiana, Il rosso segno della follia (Hatchet for the Honeymoon, 1970) and Reazione a catena (A Bay of Blood/Blood Bath, 1971). Those three pictures, all directed by Bava (though Five Dolls for an August Moon was the only one of the three films on which Bava didn’t also act as cinematographer), showcase the diversity of the thrilling all’italiana. In stark contrast with the ‘bodycount’/whodunit approach of Blood and Black Lace, Hatchet for a Honeymoon is a dry, subversive thriller whose narrative is focalised through the point-of-view of the film’s murderer, John Harrington (Stephen Forsyth). Harrington is a respectable businessman who lives a double life as a cold blooded killer; through the presentation of the narrative from his perspective, we come to understand his crimes, in the manner of Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Unlike Blood and Black Lace, Hatchet for a Honeymoon is remarkable restrained, with very little in the way of overt violence. By contrast, A Bay of Blood is very graphic in its depiction of violence, and retains the whodunit plotting of Blood and Black Lace, the identity of the murderer/s remaining a mystery until the film’s climax. Sandwiched in between Hatchet for a Honeymoon and Bay of Blood, Five Dolls for an August Moon takes the whodunit structure of Blood and Black Lace and A Bay of Blood, marrying it with the relatively bloodless aesthetic of Hatchet for a Honeymoon. Despite their differences in terms of narrative and violence, these three films within Bava’s body of work share a common theme: a depiction of the powerful – especially powerful men who are motivated by greed – as corrupt, and the notion of greed and self-interest as the key motivators behind acts of violence.

The film takes place on an island where the luxurious modernist home of George Stark (Teodora Corrà) and his wife Jill (Edith Meloni) plays host to several couples: Nick (Maurice Poli) and his wife ‘Pook’/Marie (Edwige Fenech); Jack (Howard Ross) and Peggy (Helena Ronee); and Professor Fritz Farrell (William Berger; ‘Gerry Farrell’, in the English dubbed version) and his wife Trudy (Ira von Fürstenberg). Also present are Jacques, the Stark’s houseboy, and Isabel (Ely Galleani), a young woman who is in George and Jill’s care. The film takes place on an island where the luxurious modernist home of George Stark (Teodora Corrà) and his wife Jill (Edith Meloni) plays host to several couples: Nick (Maurice Poli) and his wife ‘Pook’/Marie (Edwige Fenech); Jack (Howard Ross) and Peggy (Helena Ronee); and Professor Fritz Farrell (William Berger; ‘Gerry Farrell’, in the English dubbed version) and his wife Trudy (Ira von Fürstenberg). Also present are Jacques, the Stark’s houseboy, and Isabel (Ely Galleani), a young woman who is in George and Jill’s care.

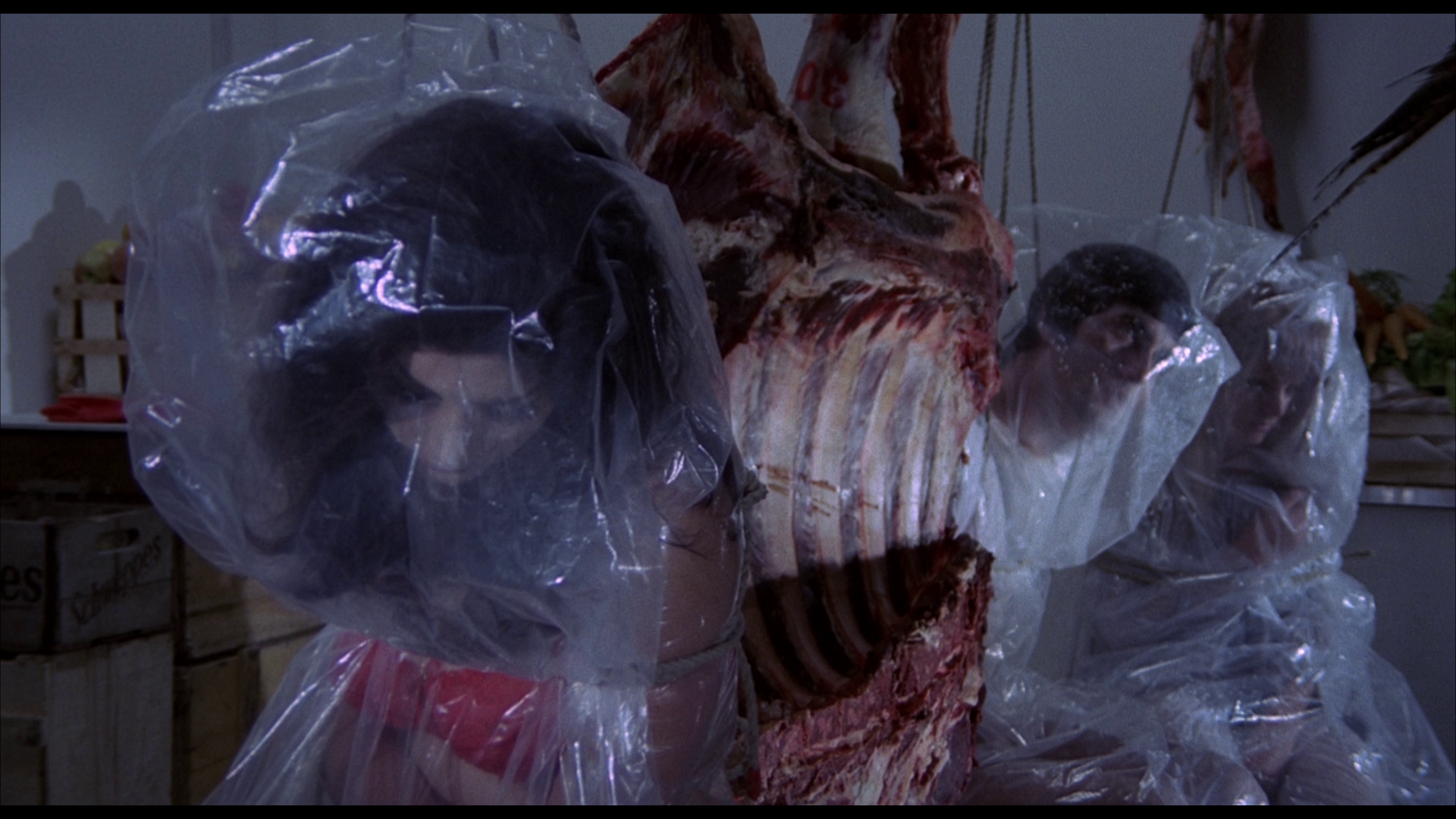

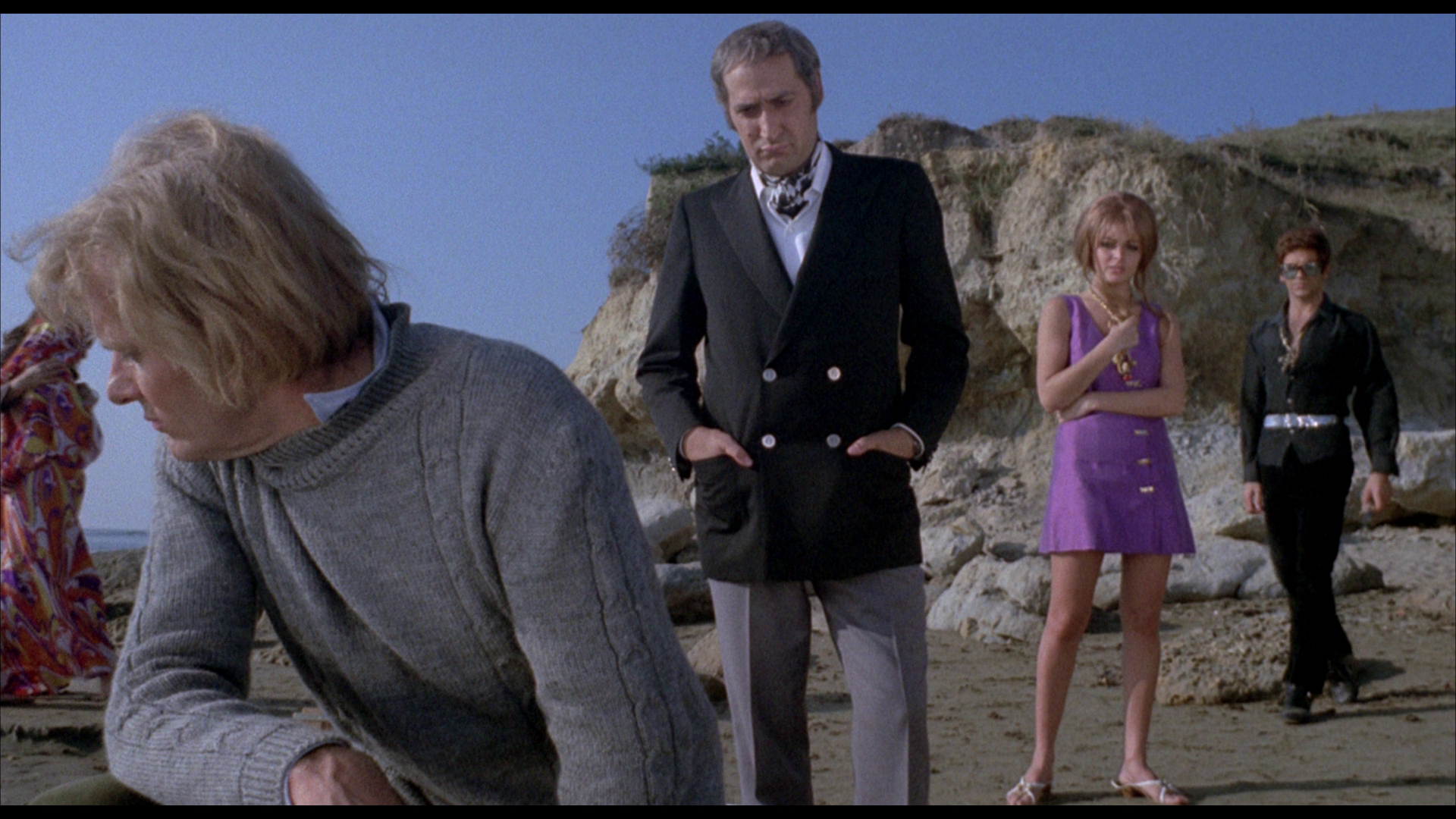

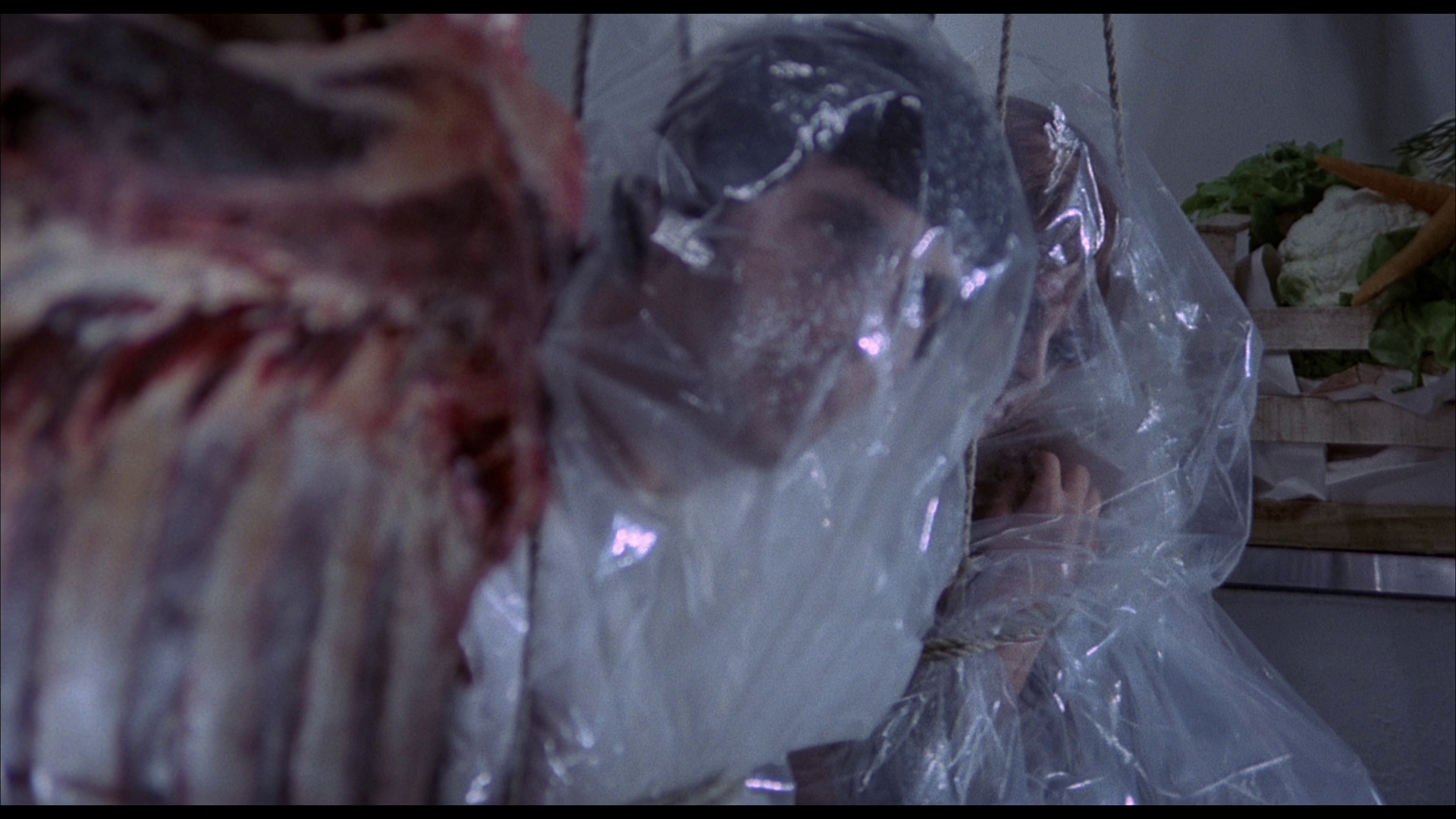

The various couples are present on the island ostensibly for a holiday, but in truth George, Nick and Jack are hoping to press Fritz to sell his formula for a new industrial resin. They offer Fritz a cool three million dollars, but Fritz refuses to sell the formula, saying that he isn’t interested in the money and intends for the formula to be used for a more socially-minded purpose. However, George has sent the yacht that connects the island to the mainland away for the weekend – ostensibly owing to the tides, but in reality, it seems, to trap Fritz on the island and wear down his resolve. However, soon the bodies begin to pile up. The first to die is Jacques, who is stabbed to death aboard his houseboat. George’s guests wrap Jacques’ body in plastic and hang it in the cold store in Jacques’ house. Gradually, the other guests are picked off one-by-one, their corpses also wrapped in plastic and stored in the cold store.  Isabel and Jacques are outsiders who look in on the bourgeois couples’ lifestyles. Isabel is connected to nature visually: she is repeatedly shown wandering on the beach, playing there like a child. These sequences underscore her sense of childlike innocence. She literally looks in on the activities of George and his group: in a number of sequences Isabel is shown outside the house, gazing in through the windows at the events taking place within. Her status as a voyeur and outsider to the group – not to mention one of its few sympathetic characters – invites the film’s viewer to see her as a cipher for the film’s audience itself. Isabel and Jacques are outsiders who look in on the bourgeois couples’ lifestyles. Isabel is connected to nature visually: she is repeatedly shown wandering on the beach, playing there like a child. These sequences underscore her sense of childlike innocence. She literally looks in on the activities of George and his group: in a number of sequences Isabel is shown outside the house, gazing in through the windows at the events taking place within. Her status as a voyeur and outsider to the group – not to mention one of its few sympathetic characters – invites the film’s viewer to see her as a cipher for the film’s audience itself.

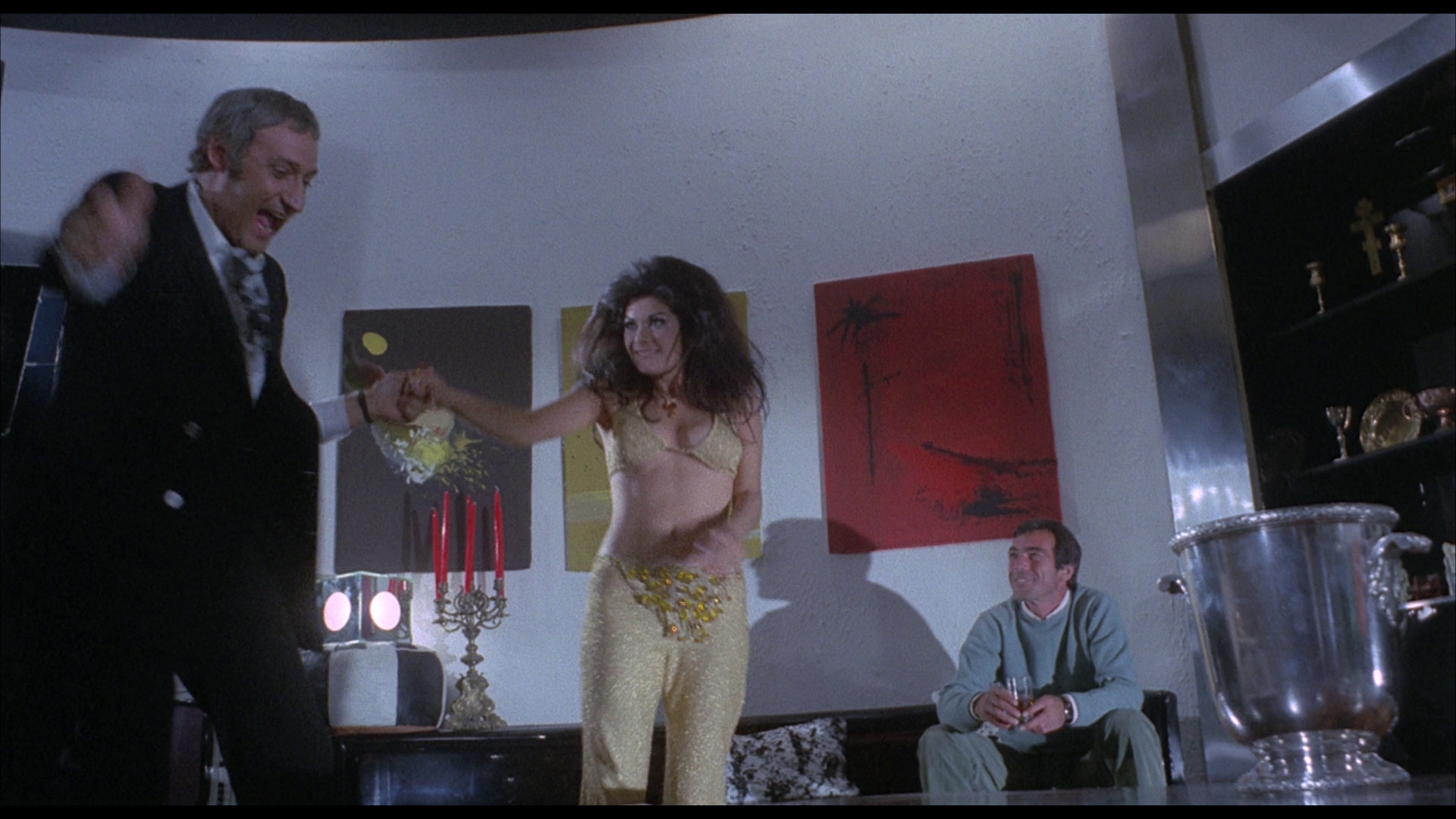

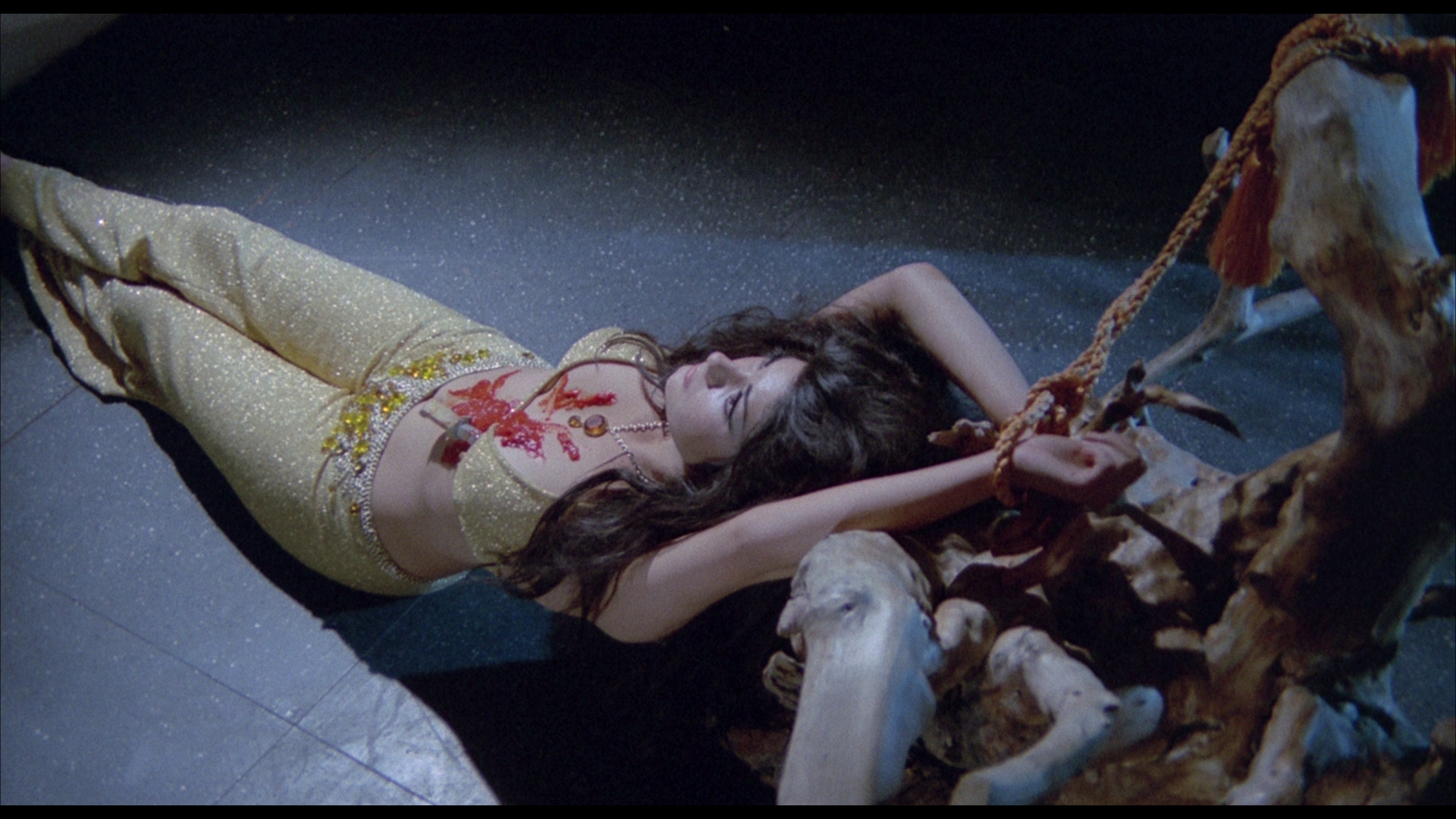

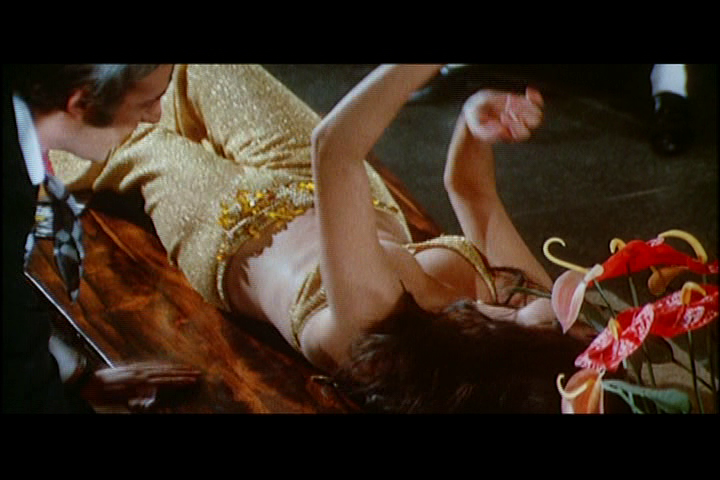

Whilst Isabel’s outsider status is reinforced by those sequences in which she is shown observing the activities of George’s group, Jacques connects with the group through his affair with Pook. He is objectified by her; her marriage to Nick is an ‘open’ one, and Pook’s liaisons with Jacques cause no jealousy within Nick, but instead result in him mocking Pook for stooping so low as to fuck a servant. For his part, Jacques resents the Starks’ bourgeois guests. With the departure of the yacht and the other employees of the Starks, during pillow talk with Pook Jacques complains that he’ll ‘have to serve everyone by myself [….] They’re so demanding. A houseboy is like a second mother for people like them’. When Pook discovers Jacques dead about his houseboat, she returns to Nick and tells him of Jacques death and her affair with him. Nick chastises Pook for her relationship with Jacques, not because Nick is jealous but because Jacques was a servant and therefore ‘beneath’ her. ‘As far as I’m concerned, it’s a matter of taste’, Nick tells Pook, ‘Why Jacques, when there are much better options?’ Nick is humiliated that his wife might use the ‘blessing’ of their open marriage to sleep with a servant. ‘I mean, did you really have to waste yourself on a houseboy?’, Nick asks her angrily. ‘I’m not wasting myself’, Pook says, explaining herself via her sense of ennui, highlighting her sexual dissatisfaction with Nick: ‘I need something to do with my time’.  The film begins with a baroque sequence which deftly sketches the decadent qualities of George and his cronies. Isabel is shown paddling in the tide, Wurlitzer music on the soundtrack. (Most likely accidentally, owing to the connection of Wurlitzer music and the coastal setting, this sequence might cause the viewer to recall Herk Harvey’s 1962 picture Carnival of Souls or Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide of 1961.) Isabel approaches the house, and the audio track is taken over by ritualistic drum music. A close-up of a record player anchors this sound as being sourced from a recording: it’s a simulacrum of a tribal gathering, rather than the real deal, filtered through the bourgeois lens of the Starks and their hangers-on. Isabel gazes through the window into the house’s living room. There, Pook is dancing erotically for the other members of the group. Keeping Pook’s face in the centre of the composition, the camera zooms in and out disorientatingly, giving the film’s viewer the feeling of being a drunken spectator to the erotic display. The men and women in the room watch on: some of the men, such as George, display unconcealed lust; others avert their eyes. The women look on with expressions of excitement, envy and reticence. (The scene is a masterclass in the Kuleshov Effect.) George approaches Pook and proposes tying her up. ‘We’re going to sacrifice a girl from the tribe to appease the god Baag’, he asserts theatrically. ‘Our most beautiful virgin, I imagine’, one of the women says ironically. It’s a performance; a game. A silver platter containing a variety of knives is passed around the guests. George cackles; Pook protests that he’s hurting her. Someone turns out the lights. When they come back on, the guests see that a knife has been plunged into Pook’s chest, a pool of blood around it. Panic ensues. However, it’s quickly revealed to be a gag, a moment of theatrics, as Nick uses soda water to wash the stage blood from Pook’s chest. With this sequence, Bava demonstrates his sense of irony and self-reflexivity, encouraging the audience to reflect on the artifice of the subsequent murders and to recognise them as examples of theatrical staging. (At least one of the murders depicted later in the film will be revealed to be a ‘fake’; and another very real murder will result in Nick asserting dryly, ‘Spraying soda water won’t work this time’.) The film begins with a baroque sequence which deftly sketches the decadent qualities of George and his cronies. Isabel is shown paddling in the tide, Wurlitzer music on the soundtrack. (Most likely accidentally, owing to the connection of Wurlitzer music and the coastal setting, this sequence might cause the viewer to recall Herk Harvey’s 1962 picture Carnival of Souls or Curtis Harrington’s Night Tide of 1961.) Isabel approaches the house, and the audio track is taken over by ritualistic drum music. A close-up of a record player anchors this sound as being sourced from a recording: it’s a simulacrum of a tribal gathering, rather than the real deal, filtered through the bourgeois lens of the Starks and their hangers-on. Isabel gazes through the window into the house’s living room. There, Pook is dancing erotically for the other members of the group. Keeping Pook’s face in the centre of the composition, the camera zooms in and out disorientatingly, giving the film’s viewer the feeling of being a drunken spectator to the erotic display. The men and women in the room watch on: some of the men, such as George, display unconcealed lust; others avert their eyes. The women look on with expressions of excitement, envy and reticence. (The scene is a masterclass in the Kuleshov Effect.) George approaches Pook and proposes tying her up. ‘We’re going to sacrifice a girl from the tribe to appease the god Baag’, he asserts theatrically. ‘Our most beautiful virgin, I imagine’, one of the women says ironically. It’s a performance; a game. A silver platter containing a variety of knives is passed around the guests. George cackles; Pook protests that he’s hurting her. Someone turns out the lights. When they come back on, the guests see that a knife has been plunged into Pook’s chest, a pool of blood around it. Panic ensues. However, it’s quickly revealed to be a gag, a moment of theatrics, as Nick uses soda water to wash the stage blood from Pook’s chest. With this sequence, Bava demonstrates his sense of irony and self-reflexivity, encouraging the audience to reflect on the artifice of the subsequent murders and to recognise them as examples of theatrical staging. (At least one of the murders depicted later in the film will be revealed to be a ‘fake’; and another very real murder will result in Nick asserting dryly, ‘Spraying soda water won’t work this time’.)

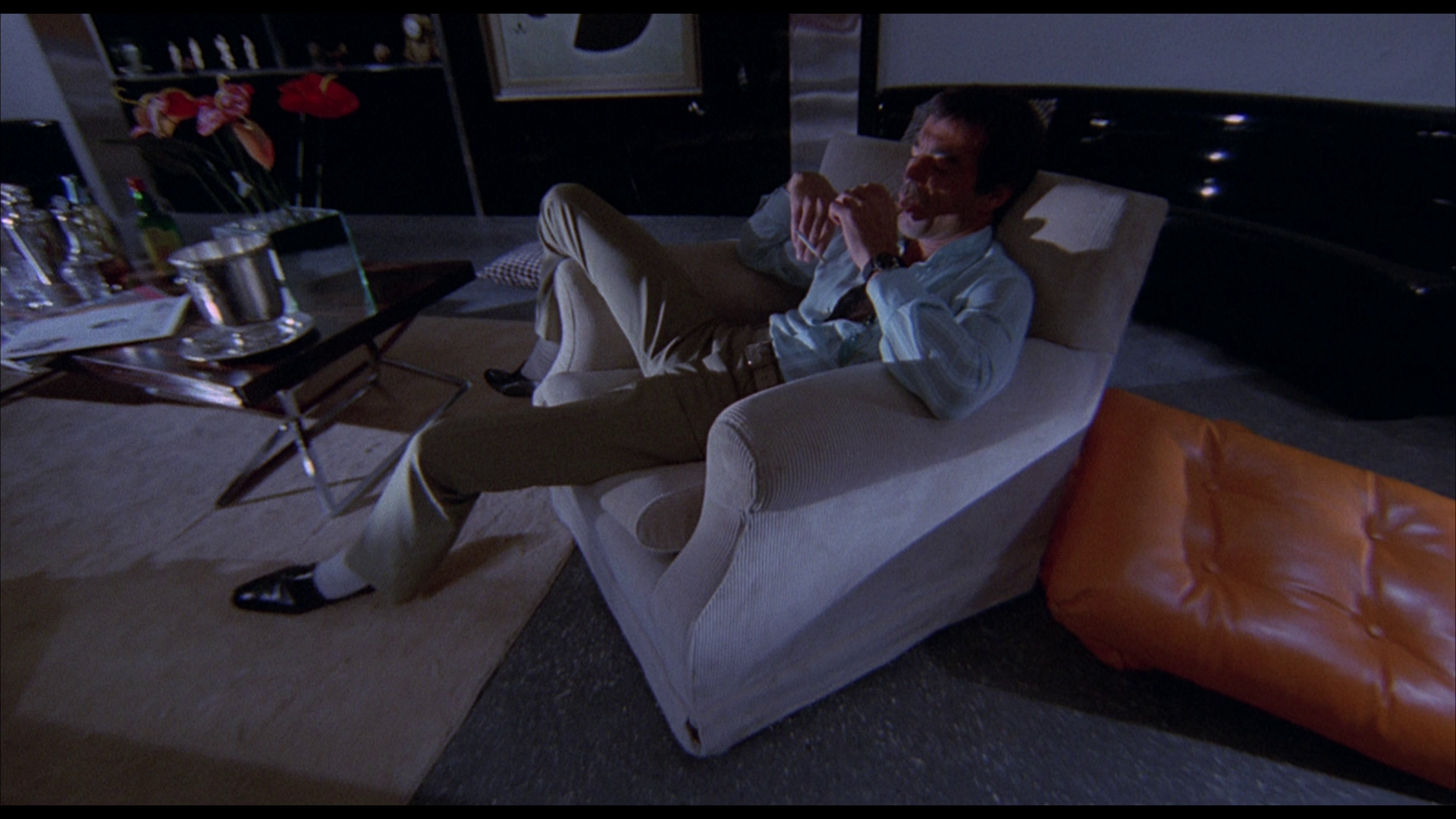

The lack of humanity within George’s guests is suggested through their cold responses to the corpses that begin to pile up; this makes each and every one of them a suspect in the murders. Following the discovery of Jacques corpse and the storing of his body in the cold store, Jack quips that the event marks ‘The first attempt ever to freeze a houseboy’. Sitting in the living room afterwards, the men drink from a bottle of whisky (J&B, naturally). ‘Houseboys come and go, but we’ll always have bottles’, Jack jokes. ‘Death makes me thirsty’, Nick says, ‘Death makes me feel dirty’. Meanwhile, George strikes his wife Jill. Trudy takes Jill to one side and advises here, ‘A woman must never talk. A woman can kill a man but she mustn’t talk about it, all right?’ As the bodies mount in the cold store, paranoia and distrust set in amongst the group (a characteristic of similar whodunit narratives set in confined spaces, admittedly), setting characters against one another and fracturing already strained relationships.  The film’s cynical worldview is reinforced by the extent to which all of the characters reveal themselves to be motivated, to one extent or another, by self-interest, and their relationships founded on fragile alliances guided by this principle. It takes several murders before Nick and George to come to an epiphany about the similarities that exist between them: ‘We’re the same’, Nick tells George towards the end of the picture, ‘We’re cut from the same cloth’. In terms of the women within the group, Trudy and Jill are gradually revealed to have been lovers prior to Jill’s marriage to George. Meanwhile, Trudy’s relationship with Fritz seems to be one of convenience: the couple are rarely seen together, and whilst unlike some of the other couples they don’t quarrel, neither do they demonstrate any warmth towards one other. Trudy seems infatuated with Jill, puzzled as to why her lover would have left her for the charmless, lecherous George. ‘How could you marry a beast like that?’, Trudy asks Jill. ‘All men are beasts’, Jill asserts, ‘But there’s something about him when he writes a cheque’. ‘So you married him for money?’, Trudy asks. ‘Twenty billion lire’, Jill says, ‘I’d have married my grandfather for that’. The film’s cynical worldview is reinforced by the extent to which all of the characters reveal themselves to be motivated, to one extent or another, by self-interest, and their relationships founded on fragile alliances guided by this principle. It takes several murders before Nick and George to come to an epiphany about the similarities that exist between them: ‘We’re the same’, Nick tells George towards the end of the picture, ‘We’re cut from the same cloth’. In terms of the women within the group, Trudy and Jill are gradually revealed to have been lovers prior to Jill’s marriage to George. Meanwhile, Trudy’s relationship with Fritz seems to be one of convenience: the couple are rarely seen together, and whilst unlike some of the other couples they don’t quarrel, neither do they demonstrate any warmth towards one other. Trudy seems infatuated with Jill, puzzled as to why her lover would have left her for the charmless, lecherous George. ‘How could you marry a beast like that?’, Trudy asks Jill. ‘All men are beasts’, Jill asserts, ‘But there’s something about him when he writes a cheque’. ‘So you married him for money?’, Trudy asks. ‘Twenty billion lire’, Jill says, ‘I’d have married my grandfather for that’.

Pressed by George, Nick and Jack to sell his formula, Fritz protests that he doesn’t want the three million dollars that they offer him collectively. ‘I’ve always said I don’t care about the money’, he tells them, ‘I just came here to rest’. He later adds that his ‘best friend was killed because of these experiments’. ‘That has nothing to do with you formula’, George says. ‘What about my conscience?’, Fritz suggests. ‘Your conscience?’, George scoffs, as if the very notion of a conscience is utterly bizarre, ‘Don’t be ridiculous’. ‘Can’t you understand that a scientist might want to work for humanity, not for millions of dollars?’, Fritz asks George in a later sequence. ‘We industrialists work for humanity too’, George informs Fritz, ‘We sell things but don’t get sentimental’. The nature of the formula is kept a secret until slightly later in the narrative, when it is revealed to be not a groundbreaking discovery in the manner that the audience might expect, something which might save lives or be used for a humanitarian purpose – it is nothing more dramatic than a new industrial resin. It’s a product which would seem to have nothing other than an industrial application. In light of this revelation, Fritz’s mooching about the island and his obstinate reluctance to sell the formula seem simply churlish.  Reflecting the trap that’s been set for him by George, Fritz is frequently imprisoned within the compositions, framed between George and Nick when they’re trying to get him to sell the formula; framed within the metal bedpost when he’s telling his wife about what has transpired; trapped visually on the spiral staircase in the centre of the Starks’ living room. ‘You’re so different from the others’, Isabel tells Fritz at one point; but her argument isn’t particularly convincing. ‘Do the maths, Professor. Once you’ve bought a yacht, a couple of Rolls Royces, and a villa with a big garden, your million dollars has gone. What do you do then, Professor?’, Isabel asks. ‘Another formula’, Fritz responds matter-of-factly. Reflecting the trap that’s been set for him by George, Fritz is frequently imprisoned within the compositions, framed between George and Nick when they’re trying to get him to sell the formula; framed within the metal bedpost when he’s telling his wife about what has transpired; trapped visually on the spiral staircase in the centre of the Starks’ living room. ‘You’re so different from the others’, Isabel tells Fritz at one point; but her argument isn’t particularly convincing. ‘Do the maths, Professor. Once you’ve bought a yacht, a couple of Rolls Royces, and a villa with a big garden, your million dollars has gone. What do you do then, Professor?’, Isabel asks. ‘Another formula’, Fritz responds matter-of-factly.

The picture is restrained in its violence, especially in comparison with what was to be Bava’s grisly next thrilling picture, Reazione a catena (A Bay of Blood/Blood Bath, 1971). However, as in A Bay of Blood, the crimes depicted within Five Dolls for an August Moon are motivated by greed. Where A Bay of Blood’s murders are precipitated by conflicts over a piece of valuable land which all of the characters wish to obtain, the killings in Five Dolls for an August Moon revolve around George, Nick and Jack’s attempts to acquire the professor’s valuable formula. Recalling a similar strategy used in the title of Bava’s iconic thrilling film Sei donne per l’assassino (‘Six Women for the Killer’, released more widely in English-speaking territories as Blood and Black Lace, 1964), the title of Five Dolls for an August Moon presumably refers to the five women (‘dolls’) on the island: Pook/Marie, Peggy, Jill, Trudy and Isabel. The association of women with ‘dolls’ and victimhood, and their foregrounding as victims, suggests a critique of patriarchy that is enacted within the film via Bava’s depiction of the male characters as cruel, greedy, heartless, manipulative and deluded. The sense of fatalism within the title, with the presentation within it of a number of victims who are to be dispatched as the narrative progresses, recalls the original title of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (1939) and the nursery rhyme from which it is sourced, Ten Little Niggers. With a narrative clearly modeled on And Then There Were None, Bava’s film adopts a very similar structure to Christie’s novel: a group of individuals are enticed to an house on an island, where they are dispatched one-by-one at the hands of an unknown killer. This very traditional ‘whodunnit’ structure makes Five Dolls for an August Moon feel rather old-fashioned in comparison with some of the broadly contemporaneous examples of the thrilling all’italiana released during the early 1970s – especially when one considers that the film was released in the same year as Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage. (Michele Lupo’s Concerto per pistola solista/The Weekend Murders, also released in 1970, offers a dry, satirical appropriation of the Agatha Christie ‘formula’; Ferdinando Baldi’s slightly later Nove ospiti per un delitto/Nine Guests for a Crime, 1977, also takes its cue from And Then There Were None.)  Like many of Bava’s other pictures, one of the joys of Five Dolls for an August Moon comes from its blacker than black humour. As each victim is dispatched by the killer, their bodies are wrapped in plastic by the survivors and hung from meathooks in the house’s walk-in cold store. This practice continues until one of the victims is discovered by the others already wrapped and hung next to the others. The narrative twists and turns but the true attraction is the photography and visual design. The film was shot over three weeks in 1969, with Tor Caldara providing the locations for the majority of the sequences set outside the house. Interiors were filmed at DEAR Studios in Rome. The Starks’ house is a cold, modernist building; at the centre of the living room is a spiral staircase leading to an upper floor which symbolises the sense of entrapment and stasis that is communicated by the film’s narrative. (The revolving bed, making a reappearance here after its initial use in Bava’s 1968 fumetti adaptation Diabolik, has a similar symbolic weight.) ‘It feels like everybody’s waiting for something that may never happen’, Jill tells Trudy at one point, and in some ways – perhaps owing to the small cast and the use of a small number of highly stylised sets and locations – the film feels very abstract and symbolic, like an unholy marriage of a whodunit plot with the Theatre of the Absurd: Agatha Christie meets Pirandello or Beckett. Like many of Bava’s other pictures, one of the joys of Five Dolls for an August Moon comes from its blacker than black humour. As each victim is dispatched by the killer, their bodies are wrapped in plastic by the survivors and hung from meathooks in the house’s walk-in cold store. This practice continues until one of the victims is discovered by the others already wrapped and hung next to the others. The narrative twists and turns but the true attraction is the photography and visual design. The film was shot over three weeks in 1969, with Tor Caldara providing the locations for the majority of the sequences set outside the house. Interiors were filmed at DEAR Studios in Rome. The Starks’ house is a cold, modernist building; at the centre of the living room is a spiral staircase leading to an upper floor which symbolises the sense of entrapment and stasis that is communicated by the film’s narrative. (The revolving bed, making a reappearance here after its initial use in Bava’s 1968 fumetti adaptation Diabolik, has a similar symbolic weight.) ‘It feels like everybody’s waiting for something that may never happen’, Jill tells Trudy at one point, and in some ways – perhaps owing to the small cast and the use of a small number of highly stylised sets and locations – the film feels very abstract and symbolic, like an unholy marriage of a whodunit plot with the Theatre of the Absurd: Agatha Christie meets Pirandello or Beckett.

Arrow’s presentation of the film is uncut and runs for 80:46 mins.

Video

Five Dolls for an August Moon is often cited as the film with which Bava’s cinema began to show a preoccupation with the use of the zoom lens. The picture also features heavy use of short focal lengths, with Bava using these to make the spaces within the Starks’ home appear to be cavernous whilst simultaneously allowing him to use the shorter hyperfocal distances of these wide-angle lenses to stage scenes in depth: in many scenes within the Stark house, we have characters and objects in both the foreground and background in focus. Five Dolls for an August Moon is often cited as the film with which Bava’s cinema began to show a preoccupation with the use of the zoom lens. The picture also features heavy use of short focal lengths, with Bava using these to make the spaces within the Starks’ home appear to be cavernous whilst simultaneously allowing him to use the shorter hyperfocal distances of these wide-angle lenses to stage scenes in depth: in many scenes within the Stark house, we have characters and objects in both the foreground and background in focus.

The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up a little over 23Gb of space on a dual-layered Blu-ray disc. From the outset, colours are shown to be bold but naturalistic, with the sky adopting a beautiful blue hue in the daylight sequences. Contrast levels are rich and deep, even in the semi-frequent day for night sequences. The impressive contrast levels, a big improvement over the film’s DVD releases, are evident from the opening nighttime sequence depicting Isabel’s wandering on the beach. There’s an impressive level of detail on display, and the presentation communicates very nicely the sense of depth within the original photography. The bravura camerawork, including the expressionistic use of the zoom lens which acts almost like a Brechtian device, communicates the decadence and debauchery of the characters. The lenses of short focal lengths, as noted above, which foreground the barrel distortion associated with wide angles are combined with the use of Dutch angles in many sequences, establishing a sense of unease within the viewer. There is some very minor damage here and there. Most noticeably, at 16:15 there is a bold vertical line which appears in one specific shot but not in the shot which is cut into it (as a cutaway); as the cutaway shot is unaffected by this vertical line, this suggests damage to the reel of the film used to shoot this scene (either as it was running through the camera or during processing) rather than to the specific source for this transfer, and owing to this will most likely be evident in all presentations of the picture. The whole shebang is presented via a robust encode which retains the structure of 35mm film, resulting in a pleasingly film-like experience. It’s on par with the Blu-ray release from Kino in the US. NB. Some larger screen grabs are included at the bottom of this review, including some grabs comparing this Blu-ray release with the film’s (first) DVD release from Image Entertainment.

Audio

The viewer is presented with the option of viewing the film in Italian (LPCM 2.0) or English (also LPCM 2.0). The Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The English track has accompanying English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, which are also optional. The viewer is presented with the option of viewing the film in Italian (LPCM 2.0) or English (also LPCM 2.0). The Italian track is accompanied by optional English subtitles. The English track has accompanying English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing, which are also optional.

Both tracks are clear and audible. The differences in content are negligible: there are some minor differences in terms of the dialogue and some of the characters’ names. Being a picture shot without sync sound, both the Italian and English tracks are technically ‘dubs’ and therefore both are equally legitimate. The Italian track is more naturalistic and convincing, though the English dub is certainly not a bad one. The Italian track seems a little shrill in comparison with the English track, with the music in the Italian track feeling a little clipped a the higher frequencies – but this may simply be a product of the original soundtrack recordings. On the other hand, the English track feels richer and more fully rounded. The inclusion of the Italian track is one major improvement over the Blu-ray released by Kino in the US; that disc only included the English dub.

Extras

The disc includes:  - a music and effects track (in Dolby Digital 2.0). - a music and effects track (in Dolby Digital 2.0).

- an audio commentary by Tim Lucas. Here, the editor of Video Watchdog and the author of a major book about Bava provides one of his characteristically breathless and information-packed commentaries. Lucas discusses Five Dolls for an August Moon’s position within Bava’s filmography as a whole and talks about some of the motifs within the picture. There’s one very slightly confusing statement made by Lucas when he suggests the film’s photography uses long lenses – over a shot that’s clearly filmed with a wide-angle lens (probably a 24 or 28mm lens, judging by the field of view). This aside, it’s an excellent, engaging track. It was recorded for the Kino release in the US and can be heard on that disc too. - the documentary ‘Mario Bava: Maestro of the Macabre’ (60:06). Made in 2000, this truly special documentary looks at Bava’s career and features contributions from members of Bava’s family (including his grandson Roy and his son Lamberto), some of his collaborators, and a number of his high profile fans (including Tim Burton and John Carpenter), alongside comments from critics Tim Lucas and Linda Williams. The documentary is narrated by Mark Kermode. The participants reflect on the trajectory of Bava’s career and the changes in people’s attitudes towards the films themselves, and also encompasses reflections upon specific films from Bava’s body of work. - the film’s trailer (2:55). The release comes with reversible artwork and one of Arrow’s characteristically beautiful booklets, including two new essays – one by Glenn Kenny, and another by Adrian Smith. Kenney’s piece looks at the film’s production, whilst the essay by Smith focuses on the film’s British distributor, Edwin John Fancey.

Overall

Often unfairly given short shrift, Five Dolls for an August Moon is perhaps best considered as one of three pictures that Bava made in relatively quick succession that seem to self-consciously highlight the diversity of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana/Italian-style thriller. Ironically, of course, the thrilling all’italiana is a genre or style (depending on your point of view) that has been the object of so much reductive criticism which uses Bava’s previous film Blood and Black Lace as the benchmark. Perhaps with Five Dolls, Hatchet for a Honeymoon and A Bay of Blood, Bava felt the need to push against the perception of the Italian-style thriller as driven by the paradigms established in Blood and Black Lace and consolidated in the thrilling films that followed, including of course Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, released in the same year as Five Dolls for an August Moon. Like many of Bava’s pictures, Five Dolls for an August Moon is deliciously blackly comic and displays a deeply cynical worldview, underscoring the repressive nature of patriarchy and exposing the greed of its bourgeois protagonists. Often unfairly given short shrift, Five Dolls for an August Moon is perhaps best considered as one of three pictures that Bava made in relatively quick succession that seem to self-consciously highlight the diversity of the thrilling all’italiana or giallo all’italiana/Italian-style thriller. Ironically, of course, the thrilling all’italiana is a genre or style (depending on your point of view) that has been the object of so much reductive criticism which uses Bava’s previous film Blood and Black Lace as the benchmark. Perhaps with Five Dolls, Hatchet for a Honeymoon and A Bay of Blood, Bava felt the need to push against the perception of the Italian-style thriller as driven by the paradigms established in Blood and Black Lace and consolidated in the thrilling films that followed, including of course Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage, released in the same year as Five Dolls for an August Moon. Like many of Bava’s pictures, Five Dolls for an August Moon is deliciously blackly comic and displays a deeply cynical worldview, underscoring the repressive nature of patriarchy and exposing the greed of its bourgeois protagonists.

Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains a very good presentation of the main feature that is distinguished from the American Blu-ray released by Kino owing to Arrow’s inclusion of the film’s Italian dub. Arrow’s disc also includes some very good contextual material including Lucas’ commentary track and the documentary about Bava. It’s an excellent release of an entertaining film. Comparison with the Image Entertainment DVD. Image Entertainment DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

Image Entertainment DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

Image Entertainment DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

Image Entertainment DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

Image Entertainment DVD:

Arrow Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|