|

|

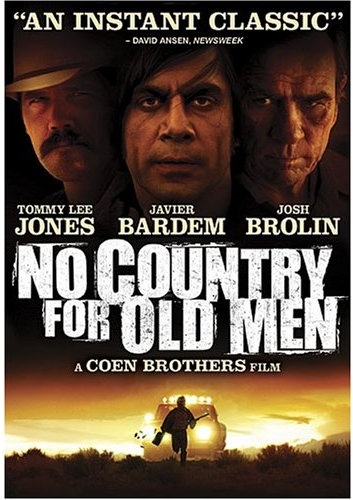

No Country For Old Men

R1 - America - Miramax Pictures Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (8th March 2008). |

|

The Film

Joel and Ethan Coen have had a turbulent relationship with both critics and general audiences; they have fluctuated between commercial and critical neglect, outright disapproval and praise. Their films are sometimes criticised as being filled with too much abstract (or sometimes 'empty') symbolism, and their selfconscious and deconstructionist approach to the Classical Hollywood genres (the film noir, the gangster picture and the Western) that their first few films refer to is refreshing but sometimes seems almost anti-commercial. At times, the Coens seem almost deliberately to challenge their audience’s perception of their work: for example, following the success of their blackly comic crime thriller Fargo, the Coens delivered The Big Lebowski, a film which could best be described as an anti-crime thriller, an out-and-out parody of the genre. As with many of the Coens' other films, at the time of its release The Big Lebowski was a commercial ‘flop’, but during the last decade the film has acquired a strong 'cult' following. Nevertheless, No Country For Old Men has been almost universally praised, and after two films (The Ladykillers and Intolerable Cruelty) which have been seen by the Coens’ fans as ‘too commercial’, No Country… represents an exceptional return to form for the brothers. (That said, it seems likely that due to its critical success, like Fargo before it No Country For Old Men will now reach a wider audience than it was designed for, and as with other films that have encountered a similar situation--for example, Pulp Fiction in 1994--the inevitable 'backlash' against the film will take place.) The Coens’ work evidences an ongoing fascination with Hollywood cinema of 1930s and 1940s, and especially the crime/noir film. The Coens' work often seeks to deconstruct these genres. Their first film, Blood Simple, was a postmodern play on the conventions of noir, infused with elements of the Western; Miller’s Crossing was a pastiche of 1930s gangster films; Barton Fink was a borderline crime film that used the themes of the noir picture in a seemingly metaphoric (and highly astract) way; delivered at the height of the neo-noir movement of the late 1980s and 1990s, Fargo was a reworking of noir themes but shifted its focus away from the noir-esque ‘fall guy’ (William H. Macy, whose character seems almost straight out of a Cornell Woolrich or David Goodis story) onto the policewoman investigating the crime; The Big Lebowski delivered a deconstruction of the Los Angeles-set Raymond Chandler-esque noir narrative; The Man Who Wasn’t There refers explicitly to the 1940s crime picture, but towards its closing sequences begins to introduce a bizarre subplot involving extraterrestrials. On the other hand, Raising Arizona and The Hudsucker Proxy are both overtly indebted to the screwball comedies of the 1930s and 1940s; O Brother, Where Art Thou? uses the 1941 film Sullivan’s Travels as a springboard for a picaresque journey through American culture of the 1930s; and Intolerable Cruelty and The Ladykillers are also films that refer back to the comedy pictures of the 1930s and 1940s. No Country For Old Men is no exception to this trend, marrying the conventions of the crime film onto some of the themes (and the imagery) associated with the 'transitional Western', a subgenre of the Western film which focuses on a society on the cusp of change. The Coens’ films are all in some way about masculinity, and this is evidenced in their ongoing fascination with the genres of film noir and the Western: their films frequently investigate what it means to be a man, and often their films revolve around a man who feels that his masculinity is undermined by his domestic role and who finds his masculinity under question (Blood Simple, Fargo, The Man Who Wasn’t There, Raising Arizona), or they occasionally revolve around a man who has become separated from his domestic role (O Brother, Where Art Thou?); often they focus on characters whose actions parody stereotypically male behaviour. In No Country For Old Men, this theme is explored through the character of Llewellyn Moss (Josh Brolin), a Vietnam veteran who stumbles across the aftermath of a drug-deal-gone-bad. Moss takes a suitcase of money from the scene and finds himself pursued by the assassin Chigurh (Javier Bardem). Moss is a classic Coen character: a man who has been domesticated through marriage but yearns for adventure and excitement, and who seems unable to fully connect with those around him, including his wife Carla Jean (Kelly MacDonald). However, Moss is far more resourceful than either Dan Hedaya’s character in Blood Simple or Billy Bob Thornton’s character in The Man Who Wasn’t There, and in the first hour of the film some of the best scenes revolve around Moss trying to solve the problem that confronts him: how to escape with the money. (Nevertheless, as the film’s tagline tells us, ‘There are no clean getaways’.) However, Moss isn’t the sole protagonist of No Country For Old Men: although much of the film focuses on Moss, the narrative is largely delivered through the perspective of Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones), a sheriff who is nearing retirement. Bell’s narration opens the film, and Bell’s comments also form the core of the film’s closing scene, which has been criticised as ‘anti-climactic’ but which neatly ties together the film’s themes. These themes are established in Bell’s opening narration, which pinpoints his feelings of alienation in a world that is changing so rapidly; Bell’s comments are underscored by the visuals, which depict Chigurh escaping from police custody and murdering a civilian with a high-tech device, a pneumatic cattle gun. Set during the early 1980s, the film constantly pits an older world (and seemingly more innocent world, in which Bell laments that a sheriff could work through his career without carrying a gun) against the cynical modern world, in which Chigurh is hired by big business to protect their ‘investment’ in the drug trade and uses high technology in order to carry out his work (which is essentially that of a hired killer). In this way, No Country For Old Men is essentially a hybrid of the crime film and the classic ‘transitional Western’, which represents a society on the cusp of change. Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is a key transitional Western that depicts the conflict between a new world of business, finance and the killers they hire to do their bidding (Pat Garrett, played by James Coburn), and the older society of outlaws who, for Peckinpah, represent the positive value of community that the modern world lacks. Likewise, No Country For Old Men is set at the beginning of the 1980s, and in the film both Bell and Moss represent an older way of life: Moss is introduced hunting, and lives a fairly simple life in a trailer park; Bell seems constantly set back by the modern world. Both Moss and Bell are left almost powerless in the face of the technology-friendly Chigurh and the financial empire for which he acts as an agent. The major theme of Cormac McCarthy’s novel is a lament for the passage of time, and this is carried through in the Coens’ excellent film adaptation. A key moment in both the novel and the film is Ed Tom Bell’s recollection of a dream in which he is on horseback and sees his father riding ahead, ‘carrying fire in a horn, the way they used to’, and knows that his father is riding ahead, in the darkness, to light a fire so that they will both be kept warm. However, as Bell notes at the end of the monologue, ‘And then I woke up’: there is the realisation that the modern world lacks a cohesive sense of community and is dominated by the cold and manipulative values of business, which in this film is associated with criminality (hired killers and drugs). As Bell’s recollection of his dream indicates, in the modern world nobody will ride ahead of us, in the dark, to light a fire so that we may keep warm. Nevertheless, despite this downbeat theme the film is filled with the kind of rich black humour that characterises the Coens’ work, and some of the scenes involving the character of Chigurh manage to be both chilling and darkly humorous. The film also benefits from some gorgeous cinematography by Roger Deakins, and a low-key but very effective score by the Coens’ frequent collaborator Carter Burwell. All of this adds up to one of the best films of 2007, and an excellent adaptation of McCarthy’s novel. No Country For Old Men is a film that is rich in theme and drama, a challenging and often visually stunning film.

Video

The Miramax DVD release contains an excellent presentation of the film that showcases Deakin's gorgeous cinematography, which is dominated by browns, reds and oranges. The film places its daylight scenes in juxtaposition with some very atmospheric night scenes, and all of these are well-presented on this DVD. The film is presented in an aspect ratio of 2.35:1, with anamorphic enhancement.

Audio

The DVD contains an English Dolby Digital 5.1 soundtrack, which contains some atmospheric directional effects and really shines during the explosions of violence that take place throughout the film. Often, the film contains moments of silence that are interrupted by loud sounds (such as gunshots), and the audio track on this DVD handles those sequences very well. There are optional subtitles in French, Spanish and English (for the Hard of Hearing).

Extras

The Coens are notoriously reluctant to talk about the themes of their films, preferring to let their films speak for theirselves. Consequently, the contextual material on this DVD contains little direct input from either Joel or Ethan Coen. The DVD contains three documentaries: -'Working With the Coens' (8:07). A series of interviews with the cast of No Country For Old Men, who reflect on their feelings about the Coens and their work. -'The Making of "No Country For Old Men"' (24:28). This short documentary comments on the production of the film; it's the most substantial documentary on the DVD, and the interviewees (including the Coens) show some strong insight into the film and its themes, but the documentary feels much too short and seems ultimately more like a promotional piece rather than a serious discussion of the film. -'Diary of a Country Sheriff' (6:44). Tommy Lee Jones reflects on the character he plays in the film. The disc also contains some bonus trailers, for 'National Treasure 2', 'Gone Baby Gone' and 'Dan in Real Life'.

Packaging

The DVD comes in a standard Amaray keep-case, with a cardboard outer slipcase.

Overall

No Country For Old Men is an exceptional film, a very strong adaptation of an excellent novel. It's one of the best pictures within the Coens' body of work. However, despite its black humour it's a very downbeat film, and it's certainly not an action-oriented picture. The film is highly recommended, and this DVD contains a fine presentation of the film with some adequate contextual material.

|

|||||

|