|

|

Culpepper Cattle Co. (The) (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Signal One Entertainment Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (2nd February 2017). |

|

The Film

The Culpepper Cattle Co. (Dick Richards, 1972) The Culpepper Cattle Co. (Dick Richards, 1972)

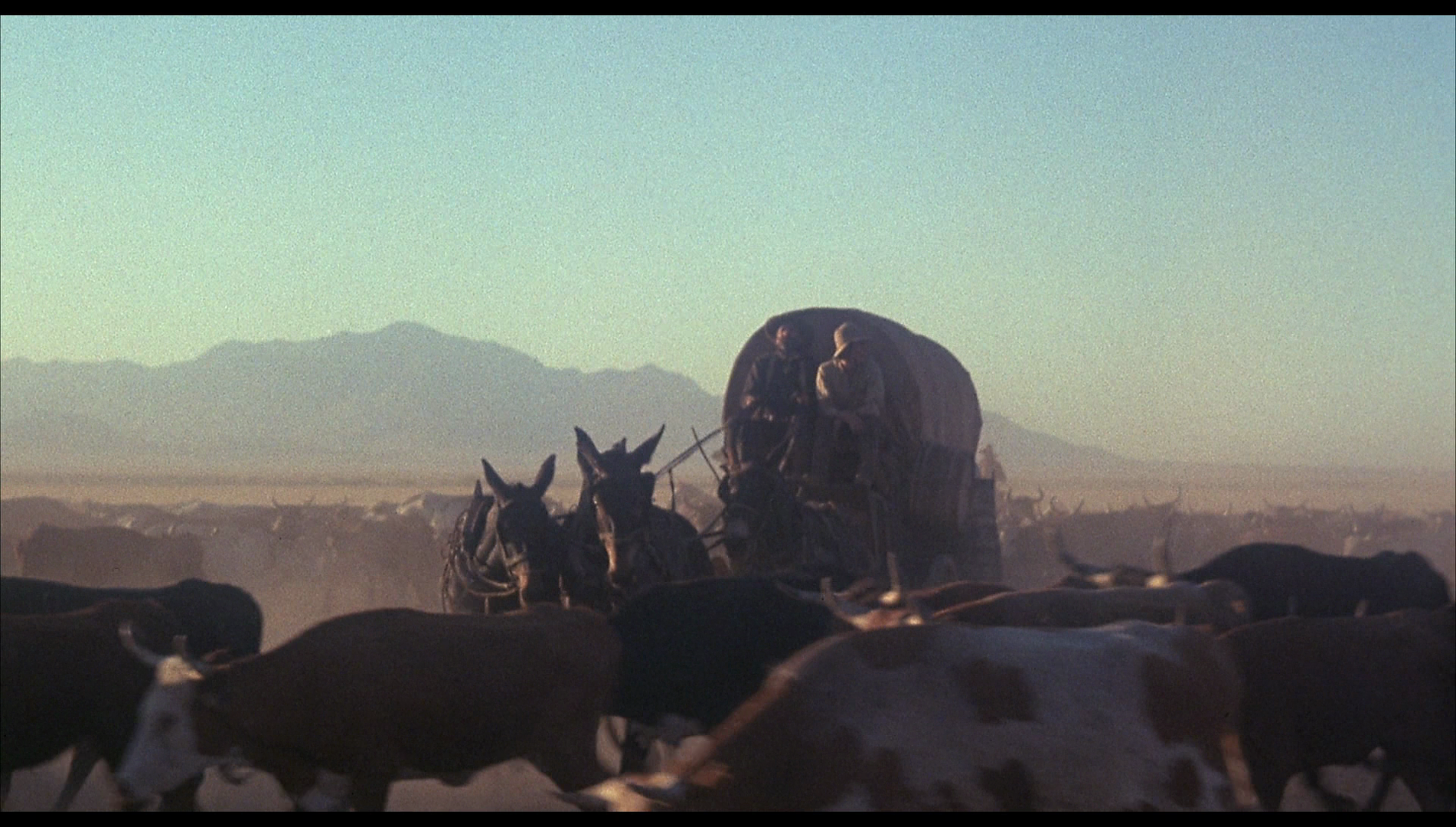

Made during the early 1970s, Dick Richards’ The Culpepper Cattle Co. (1972) is a clear example of a revisionist Western; it is a film that openly questions the mythologising of classic film Westerns via its depiction of the hardships of life in the West. Like a number of other revisionist Westerns of the era – for example, Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) or Frank Perry’s Doc (1971, also recently released on Blu-ray by Signal One Entertainment and reviewed by us here) - The Culpepper Cattle Co. seeks authenticity in its mise-en-scène. The characters’ costumes are dirty, their environments worn and looking ‘lived-in’. The actors aren’t the glamorous stars of previous Hollywood Westerns; their faces look as ‘lived-in’ as their clothes. It’s an open challenge to the sanitised representation of the West that, via a sense of visual and narrative realism (which in the context of these 1970s Westerns was synonymous with an exceptionally bleak worldview), was seen to characterise Hollywood Westerns of previous eras. Writing about The Culpepper Cattle Co. upon its first release in 1972, Judith Crist suggested that the picture ‘looks as if it might have been torn from the pages of an American Heritage history, supplemented by old photos found in a desert ghost-town shack and pieced out with half-memories of incidents reported by aging cowpokes’ (Crist, 1972: 56). The film itself begins with such photographs, the opening titles playing out over sepia-tinted photographs that have the look of authentic period portraits of settler and cowboys. (Interestingly, Dick Richards began his career as a stills photographer.) Similar montages of still photographs were featured in the opening credits sequences of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969) and the later Posse (Mario Van Peebles, 1993).  The film focuses on young Ben Mockridge (Gary Grimes), who makes the decision to join Frank Culpepper’s (Billy Green Bush) cattle drive to Fort Lewis, Colorado. Ben approaches Culpepper asking for a job, and Culpepper assigns Ben the role of the cattle drive’s ‘Little Mary’ – assistant to the cook. When some of the cattle stampede one night, killing a cowboy, Ben witnesses his first death. This is followed shortly afterwards by Ben’s witnessing of his first gunfight, when Culpepper challenges a group of men who are holding two hundred head of the cattle ransom; Culpepper’s challenge results in a gunfight in which the men holding the cattle are killed and a number of Culpepper’s cowboys are also shot dead. The film focuses on young Ben Mockridge (Gary Grimes), who makes the decision to join Frank Culpepper’s (Billy Green Bush) cattle drive to Fort Lewis, Colorado. Ben approaches Culpepper asking for a job, and Culpepper assigns Ben the role of the cattle drive’s ‘Little Mary’ – assistant to the cook. When some of the cattle stampede one night, killing a cowboy, Ben witnesses his first death. This is followed shortly afterwards by Ben’s witnessing of his first gunfight, when Culpepper challenges a group of men who are holding two hundred head of the cattle ransom; Culpepper’s challenge results in a gunfight in which the men holding the cattle are killed and a number of Culpepper’s cowboys are also shot dead.

His numbers dwindling, Culpepper orders Ben to ride to a nearby town, Castigo, and there enlist the help of Russ Caldwell (Geoffrey Lewis). On his way to Castigo, Ben stops to take a shit and two fur trappers hold him at gunpoint, taking Ben’s horse and his gun. Ben walks the rest of the way to the town and finds Caldwell, who we soon realises is a hired gun rather than a cowboy. Caldwell vows to work for Culpepper, along with Caldwell’s associates Dixie Brick (Bo Hopkins), Missoula (Wayne Sutherlin) and Luke (Luke Askew). On their way back to Culpepper’s cattle drive, Caldwell and the others find the fur trappers and kill them, returning Ben’s horse and gun back to him. When Ben and the others return to Culpepper, Ben volunteers for night watch. Culpepper is doubtful at first but, finding himself short of men willing to perform this duty, gives the boy a chance to fulfill a role other than that of the cook’s ‘Little Mary’. However, during the night rustlers attack Ben and steal a number of Culpepper’s horses. Culpepper and his men ride into a town where they find the thief in a saloon, thanks to Ben’s help. Ben is forced to kill a man in self-defence, and with the aid of Caldwell’s gang Culpepper manages to best the horse thieves. However, back at the camp Caldwell reveals himself to be something of a bully, threatening one of the cowboys to the point that the cowboy leaves the cattle drive rather than become involved in a duel with the seasoned gunslinger.  Culpepper’s cattle trample over a fence, and Culpepper rides into another town to try to find out whose land the cattle are on, with the intention of making reparations. He discovers that the land is owned by Thornton Pierce (John McLiam). Flanked by his employees, Thornton Pierce threatens Culpepper, angering Caldwell by stripping Culpepper’s men of their guns – including Caldwell’s prized pearl-handled revolver. Thornton Pierce demands Culpepper and his cowboys leave, and Culpepper relents – much to Caldwell’s chagrin. Culpepper’s cattle trample over a fence, and Culpepper rides into another town to try to find out whose land the cattle are on, with the intention of making reparations. He discovers that the land is owned by Thornton Pierce (John McLiam). Flanked by his employees, Thornton Pierce threatens Culpepper, angering Caldwell by stripping Culpepper’s men of their guns – including Caldwell’s prized pearl-handled revolver. Thornton Pierce demands Culpepper and his cowboys leave, and Culpepper relents – much to Caldwell’s chagrin.

The cowboys drive the cattle to a small community of settlers, a religious order headed by Nathaniel Green (Anthony James). Green preaches equality, telling Culpepper and his men that ‘We are all brothers and sisters here, all children of God’. Ben is fascinated with Green’s doctrine and listens carefully to Green’s assurance that ‘Here man can live without violence and without bloodshed’. However, Thornton Pierce rides out to the community with his men and confronts Culpepper, also challenging Green: the religious community has, it seemed, settled on land belonging to Thornton Pierce. However, Green tells the landowner that the territory is ‘God’s land’ and he refuses to move the settler group from it. Thornton Pierce promises to return, and when he returns to the site he vows that ‘We’re coming in to blast whatever trespassers is left’. Green asks Culpepper for help in fighting Thornton Pierce’s men, as Green’s community has forsworn violence of any kind. Culpepper refuses, but Ben sees this as a chance to ‘do it right’.  As the film begins, Ben expresses his romantic ideas regarding the work of cowboys, which is combined with a fascination with violence. Before approaching Culpepper, he shows his friend Tim (Charles Martin Smith) the gun he has bought. ‘Your ma doesn’t know you got it, huh?’, Tim asks, admiring the weapon, ‘Can you do it?’ In response to this, Ben shows Tim his quickdraw, informing his friend that he plans to ask Frank Culpepper for a job. These two teenaged boys are shown to be fascinated with the world of men, guns and cattle drives; their romantic delusions regarding a cowboy’s life might be those of the film’s audience, and it is these delusions that the film shatters as its narrative progresses. When Ben approaches Culpepper, he tells him ‘I really wanna go’. ‘Why?’, Culpepper asks. ‘’Cause I wanna be a cowboy’, Ben asserts, ‘I want it more than anything, Mr Culpepper’. ‘Well, that’s one hell of an ambition, boy’, Culpepper says in response. As the film begins, Ben expresses his romantic ideas regarding the work of cowboys, which is combined with a fascination with violence. Before approaching Culpepper, he shows his friend Tim (Charles Martin Smith) the gun he has bought. ‘Your ma doesn’t know you got it, huh?’, Tim asks, admiring the weapon, ‘Can you do it?’ In response to this, Ben shows Tim his quickdraw, informing his friend that he plans to ask Frank Culpepper for a job. These two teenaged boys are shown to be fascinated with the world of men, guns and cattle drives; their romantic delusions regarding a cowboy’s life might be those of the film’s audience, and it is these delusions that the film shatters as its narrative progresses. When Ben approaches Culpepper, he tells him ‘I really wanna go’. ‘Why?’, Culpepper asks. ‘’Cause I wanna be a cowboy’, Ben asserts, ‘I want it more than anything, Mr Culpepper’. ‘Well, that’s one hell of an ambition, boy’, Culpepper says in response.

After saying goodbye to his mother, in a poignant and quiet moment in which Ben’s mother’s lack of words underscores her ambivalence about the situation, Ben joins the cattle drive and is given the position of the drive’s ‘Little Mary’ – assistant to the cook. Riding with the cook, Ben tells his new companion ‘I’ve never been up north before’. The cook’s response offers the film’s first challenge to Ben’s romantic ideas about the life of a cowboy: ‘Wait till you get to the desert’, the cook says dryly, ‘Sand scorching your eyeballs. Driving through country that ain’t fit for scavengers. Dry enough to make you drink your own piss’. ‘I guess all I wanna do is punch cows and ride and cowboyin’. There’s nothing better than that’, Ben asserts. ‘Like hell there ain’t’, the cook sneers, ‘Kid, cowboyin’ is something you do when you can’t do nothin’ else’. The cook’s response to Ben’s romanticisation of the life of a cowboy emblematises the film’s depiction of ‘cowboyin’ as a proletarian occupation, a thankless and unromantic lifestyle characterised by wage slavery and unsavoury living and working conditions. As David Lusted says, the film features scenes that focus on ‘workplace harassment and bullying of men and cattle’ (Lusted, 2014: 225). For example, Ben is mocked when his misunderstands one of the cowboy’s command that Ben picket the cowboy’s horse for him: when Ben tries to mount the horse instead of leading it to the picket by its reins, the horse throws Ben, and Ben becomes the subject of much laughter.  As the cattle drive progresses, Ben’s romantic delusions about the life of a cowboy become shattered at an escalating rate: some of the members of Culpepper’s company leave ‘the trail when violence is threatened […] and others die haunting, explicit deaths in random accidents as much as in the final gunplay’ (ibid.: 225). During one sequence, the cattle stampede, overturning the cook’s wagon and killing one of the cowboys in the process: driving cattle is thus shown to be a process fraught with danger. This danger comes not only from the cattle but from other people too: following the stampede, two hundred of the cattle are found in a canyon, where they are held ransom by a group of men who demand Culpepper pay them a reward – ‘say, fifty cents a head’. Culpepper refuses and, in anticipation of violence, the cattle boss shoots first, killing the old man with whom he is negotiating the return of the cattle. A gunfight ensues, witnessed by Ben, in which several of Culpepper’s me are killed and all of the group who are holding the cattle are shot dead. This is the first incident in which Ben witnesses violent death, and the focus in the scene is on the shock and horror on Ben’s face as he watches these two groups of men slaughter one another. The sequence, as with many others in the film, offers a depiction of one of the motifs of many revisionist Westerns of the era: innocents as witness to slaughter, their horror at the violence unfolding in front of their eyes acting as a metaphor for the shock of the films’ audiences at the depiction of violence in more graphic ways than Western films of previous eras owing to the use of blood squibs and the close-ups of injury details. Ben watches, shocked, as Culpepper guns down the old man who acts as spokesman for the cattle thieves, a close-up shot of the old man’s face as the bullet hits him in the gut showing blood spraying out of his mouth. We might recall, for instance, the children that hold one another as men die around them during the opening sequence of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) or Peter Strauss’ young, inexperienced soldier’s wide-eyed and helpless witnessing of the brutality of the massacre of Native Americans at Sand Creek by members of Colonel John Chivington’s militia in Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, 1970). Or perhaps a more immediate comparison is the witnessing by the young boys, hired as cowhands by John Wayne’s character, of the murder of their mentor at the hands of a demented drifter (Bruce Dern) in Mark Rydell’s The Cowboys (1972). As the cattle drive progresses, Ben’s romantic delusions about the life of a cowboy become shattered at an escalating rate: some of the members of Culpepper’s company leave ‘the trail when violence is threatened […] and others die haunting, explicit deaths in random accidents as much as in the final gunplay’ (ibid.: 225). During one sequence, the cattle stampede, overturning the cook’s wagon and killing one of the cowboys in the process: driving cattle is thus shown to be a process fraught with danger. This danger comes not only from the cattle but from other people too: following the stampede, two hundred of the cattle are found in a canyon, where they are held ransom by a group of men who demand Culpepper pay them a reward – ‘say, fifty cents a head’. Culpepper refuses and, in anticipation of violence, the cattle boss shoots first, killing the old man with whom he is negotiating the return of the cattle. A gunfight ensues, witnessed by Ben, in which several of Culpepper’s me are killed and all of the group who are holding the cattle are shot dead. This is the first incident in which Ben witnesses violent death, and the focus in the scene is on the shock and horror on Ben’s face as he watches these two groups of men slaughter one another. The sequence, as with many others in the film, offers a depiction of one of the motifs of many revisionist Westerns of the era: innocents as witness to slaughter, their horror at the violence unfolding in front of their eyes acting as a metaphor for the shock of the films’ audiences at the depiction of violence in more graphic ways than Western films of previous eras owing to the use of blood squibs and the close-ups of injury details. Ben watches, shocked, as Culpepper guns down the old man who acts as spokesman for the cattle thieves, a close-up shot of the old man’s face as the bullet hits him in the gut showing blood spraying out of his mouth. We might recall, for instance, the children that hold one another as men die around them during the opening sequence of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) or Peter Strauss’ young, inexperienced soldier’s wide-eyed and helpless witnessing of the brutality of the massacre of Native Americans at Sand Creek by members of Colonel John Chivington’s militia in Soldier Blue (Ralph Nelson, 1970). Or perhaps a more immediate comparison is the witnessing by the young boys, hired as cowhands by John Wayne’s character, of the murder of their mentor at the hands of a demented drifter (Bruce Dern) in Mark Rydell’s The Cowboys (1972).

When Ben is asked to seek the services of Russ Caldwell at Castigo, he believes that he is hiring another cowboy. However, the exact role of Caldwell and his associates Luke, Missoula and Dixie Brick is revealed when the four men, and Ben, stumble across the two trappers who stole Ben’s horse and gun. Caldwell and his crew approach the trappers, confronting them about their robbery of Ben before shooting them in the back. ‘Get your stuff, kid’, Russ orders Ben after the trappers have been killed. With this scene, Caldwell and his men are identified for the film’s audience (and for Ben) as ruthless, cold-blooded killers – not above shooting a man in the back, an action which in many classical Westerns would be enacted by the film’s villain rather than by an ally of the protagonist. When Ben is asked to seek the services of Russ Caldwell at Castigo, he believes that he is hiring another cowboy. However, the exact role of Caldwell and his associates Luke, Missoula and Dixie Brick is revealed when the four men, and Ben, stumble across the two trappers who stole Ben’s horse and gun. Caldwell and his crew approach the trappers, confronting them about their robbery of Ben before shooting them in the back. ‘Get your stuff, kid’, Russ orders Ben after the trappers have been killed. With this scene, Caldwell and his men are identified for the film’s audience (and for Ben) as ruthless, cold-blooded killers – not above shooting a man in the back, an action which in many classical Westerns would be enacted by the film’s villain rather than by an ally of the protagonist.

When Ben is attacked by the rustlers whilst on night watch, he is chastised by Culpepper for not shooting the thieves. ‘Why the hell didn’t you shoot them?’, Culpepper asks him demandingly. ‘I wanted to, Mr Culpepper’, Ben says, ‘I sure as hell wanted to’. ‘But you didn’t’, Culpepper responds angrily, ‘Damn stupid kid!’ Culpepper and the others ride into a town where Ben spots one of the thieves in the saloon. Missoula tells Ben to hold his gun on the bartender (‘If he moves, kill ‘im’, he says, in words that echo Pike Bishop’s advice to his crew during the opening heist of The Wild Bunch). Culpepper confronts the thief. Violence follows, with Culpepper’s men executing the thief and his associates in slow-motion (the brutality of the moment underscored by the use of squibs). Ben is faced with his own decision, kill or be killed, when the bartender reaches for a shotgun, and Ben makes the choice to shoot first. With this action, Ben has begun to tread a path of violence from which he can’t return. ‘Is he dead?’, Ben asks, shocked and concerned. ‘Deader’n hell, kid. Deader’n hell’, Dixie Brick answers coolly.  It’s difficult not to compare any Vietnam-era Western with a strong focus on violence with either Soldier Blue, The Wild Bunch, Chato’s Land (Michael Winner, 1972) or Ulzana’s Raid (Robert Aldrich, 1972). Like Soldier Blue and Ulzana’s Raid, in particular, The Culpepper Cattle Co. mirrors the structure of the classic bildungsroman formula, focusing on an innocent young man who begins the film with a strong sense of idealism and romanticism but is forced by the narrative into various situations in which he encounters extreme violence, to the point that the end of the film leaves him shattered by what he has witnessed. Philip French suggests that Ben’s ‘journey’ may perhaps be seen as the journey of America itself during the era of the Vietnam war: as the narrative progresses, Ben ‘is initiated into the squalid pleasures, the self-seeking, the random violence around him. Without ever making it too explicit, Richards seems to be implying that the Culpepper Cattle Company is America – a business ploughing relentlessly on, totally amoral, fighting when it must, compromising when it can, a few deranged or misguided members galloping off from time to time to pursue “idealistic” Vietnam-like missions on the side which neither adversary nor apparent beneficiary justifies’ (French, 2011). It’s difficult not to compare any Vietnam-era Western with a strong focus on violence with either Soldier Blue, The Wild Bunch, Chato’s Land (Michael Winner, 1972) or Ulzana’s Raid (Robert Aldrich, 1972). Like Soldier Blue and Ulzana’s Raid, in particular, The Culpepper Cattle Co. mirrors the structure of the classic bildungsroman formula, focusing on an innocent young man who begins the film with a strong sense of idealism and romanticism but is forced by the narrative into various situations in which he encounters extreme violence, to the point that the end of the film leaves him shattered by what he has witnessed. Philip French suggests that Ben’s ‘journey’ may perhaps be seen as the journey of America itself during the era of the Vietnam war: as the narrative progresses, Ben ‘is initiated into the squalid pleasures, the self-seeking, the random violence around him. Without ever making it too explicit, Richards seems to be implying that the Culpepper Cattle Company is America – a business ploughing relentlessly on, totally amoral, fighting when it must, compromising when it can, a few deranged or misguided members galloping off from time to time to pursue “idealistic” Vietnam-like missions on the side which neither adversary nor apparent beneficiary justifies’ (French, 2011).

In some ways, in its ultimate epiphany, The Culpepper Cattle Co. feels like the polar opposite to Soldier Blue. Both films culminate in an attack on a small settlement. In Soldier Blue, the climax offers a representation of the Sand Creek massacre, in a sequence that drew parallels between the actions of the militia under the command of Colonel John M Chivington at Sand Creek in 1864 and the atrocities committed by the US Army at My Lai in 1968; in The Culpepper Cattle Co., a similar climax is achieved when the group of religious settlers ask the cowboys to defend them from the landowner Thornton Pierce, who threatens the settlers with the promise of violence if they do not move off his land. (It’s impossible to discuss the film’s major themes without talking about the climax and resolution of the film, and I’ll do so here; first time viewers would do well to skip to the ‘Video’ section of this review if they do not want the story of The Culpepper Cattle Co. to be ‘spoiled’.)  As Andrew Patrick Nelson notes, in its depiction of the decision that Ben makes to stay with the religious group and protect them from the landowner Thornton Pierce – a decision that motivates the four gunmen hired by Culpepper to ‘do it right’ (to quote Pike Bishop’s famous line from The Wild Bunch) and abandon the cattle drive to help the settlers – The Culpepper Cattle Co. ‘deliberately plays off a familiar Western scenario, the “ride to the rescue”’ (Nelson, 2015: np). At first encounter, the settlement seems to offer a place free from violence: Green’s sermon to the settlers declares ‘Here men can live without violence – without bloodshed’. As Green speaks, close-ups of Ben and some of the other cowboys suggest they are intrigued and elevated by Green’s idealistic words. However, shortly afterwards Thornton Pierce rides out to the settlers with some of his men in tow, telling Green ‘You’re still on my land’. To this, Culpepper responds dryly: ‘Seems to me you got an awful lot of land. You got a deed to it?’ Thornton Pierce indicates towards his armed men: ‘These are all the deeds I need’, he says, adding to Green ‘Get off my land’. ‘God’s land’, Green corrects him. However, Green’s appeal to a higher power has no effect on Thornton Pierce: ‘We’re coming in to blast whatever trespassers is left’, he warns Green. As Andrew Patrick Nelson notes, in its depiction of the decision that Ben makes to stay with the religious group and protect them from the landowner Thornton Pierce – a decision that motivates the four gunmen hired by Culpepper to ‘do it right’ (to quote Pike Bishop’s famous line from The Wild Bunch) and abandon the cattle drive to help the settlers – The Culpepper Cattle Co. ‘deliberately plays off a familiar Western scenario, the “ride to the rescue”’ (Nelson, 2015: np). At first encounter, the settlement seems to offer a place free from violence: Green’s sermon to the settlers declares ‘Here men can live without violence – without bloodshed’. As Green speaks, close-ups of Ben and some of the other cowboys suggest they are intrigued and elevated by Green’s idealistic words. However, shortly afterwards Thornton Pierce rides out to the settlers with some of his men in tow, telling Green ‘You’re still on my land’. To this, Culpepper responds dryly: ‘Seems to me you got an awful lot of land. You got a deed to it?’ Thornton Pierce indicates towards his armed men: ‘These are all the deeds I need’, he says, adding to Green ‘Get off my land’. ‘God’s land’, Green corrects him. However, Green’s appeal to a higher power has no effect on Thornton Pierce: ‘We’re coming in to blast whatever trespassers is left’, he warns Green.

Green attempts to appeal to Culpepper, asking him to stay and fight Thornton Pierce’s men in order to help the settlers: ‘God sent you here to help us’, Green asserts. ‘All you have to do is leave’, Culpepper reminds Green. ‘We cannot’, Green responds. As Culpepper and his group begin to leave, Ben tells them he’s staying: ‘These people, they need some kind of help’, he pleas. ‘You can’t help them’, Culpepper tells him, reminding Ben of his youth and lack of experience in matters of violence, and the fact that he is massively outnumbered by Thornton Pierce’s group. ‘Some things are more important to a man than cattle, Mr Culpepper’, Ben asserts idealistically. ‘Not to me’, Culpepper responds, a true capitalist to the bitter end. Strapping on his gunbelt, Ben makes the decision to stay with the religious group – no matter how far the odds may seem to be stacked against him. The four hired guns begin to ride off with the cattle drive but turn, reflecting on Ben’s decision to stay and fight an enemy that so obviously outnumbers him (and which is much more experienced in both life and violence). After a moment of hesitation, the four gunslingers turn their horses and ride back to the settlers, the heroism of their decision underscored by the use of what Andrew Patrick Nelson calls ‘triumphant music’ (ibid.). The music and the photography reinforce the extent to which these men have made the ‘moral choice’ – an act of interventionism that seems to openly parallel the decision of the US to become involved in the Vietnam War, for example, the settlers seeming to act as a metonym for the South Vietnamese and the gunfighters symbolising the American military. (Much as in Soldier Blue, the Cheyenne inhabitants of Sand Creek metonymically represent the Vietnamese, and the militia that target them are an all too obvious representation of the American military.)  The gunfight that ensues, with Thornton Pierce’s men riding in to the settlement and killing all of Ben’s friends in brutal slow-motion, and via the heavy use of squibs to show their bodies penetrated by bullets, has some similarities with the climax of The Wild Bunch – in which, despite being greatly outnumbered and outgunned, Pike Bishop’s (William Holden) group decide to make the ‘moral choice’ to rescue their friend Angel (Jaime Sanchez) from Mapache (Emilio Fernandez), a commander in the Mexican army. As at the end of The Wild Bunch, the gunfighters’ decision is informed by a moral decision but seems ultimately nihilistic, their destruction assured simply by the fact that they face a more powerful, more heavily-equipped and more organised enemy; in some ways, their decision to commit to such an action despite the knowledge that they will almost certainly be annihilated may be seen as an act of self-destruction that signals the end of an era. (This is the reading of the climax of The Wild Bunch that tends to dominate the literature that has been written about the film.) The gunfight that ensues, with Thornton Pierce’s men riding in to the settlement and killing all of Ben’s friends in brutal slow-motion, and via the heavy use of squibs to show their bodies penetrated by bullets, has some similarities with the climax of The Wild Bunch – in which, despite being greatly outnumbered and outgunned, Pike Bishop’s (William Holden) group decide to make the ‘moral choice’ to rescue their friend Angel (Jaime Sanchez) from Mapache (Emilio Fernandez), a commander in the Mexican army. As at the end of The Wild Bunch, the gunfighters’ decision is informed by a moral decision but seems ultimately nihilistic, their destruction assured simply by the fact that they face a more powerful, more heavily-equipped and more organised enemy; in some ways, their decision to commit to such an action despite the knowledge that they will almost certainly be annihilated may be seen as an act of self-destruction that signals the end of an era. (This is the reading of the climax of The Wild Bunch that tends to dominate the literature that has been written about the film.)

The gunfighters, Ben’s friends, are killed defending a group who will not pick up arms to defend themselves; their brutal end is witnessed by Ben, a young man and relative innocent. After the battle has ended, on the soundtrack we are presented with a rendition of ‘Amazing Grace’. But the moment of heroism is undercut when Green coldly tells Ben that his group will now move on: ‘We’re leavin’’, Green says, ‘Can’t stay on this field of death. The entire valley is soaked with blood’. Ben is shocked by the realisation that his friends have sacrificed their lives for nothing. ‘What about them?’, he cries, indicating towards the corpses of his friends, ‘You’re not gonna just leave ‘em there. You gotta bury them first’. Where Soldier Blue’s depiction of a similar scenario, an assault enacted on a small community, was intended to criticise military might and violence via depicting the brutality of the militia that attack the Native American settlers at Sand Creek, The Culpepper Cattle Co. reserves its scorn for the hypocrisy of the settlers that demand the passing cowboys help defend their land and rights before criticising the violence that has been enacted in their name – suggesting that the defence of such communities may appear to be morally ‘right’ but is ultimately thankless. (Ultimately, Culpepper’s attitude, which at first glance appears dismissive of the settlers, is in retrospect the most logical one.) For her part, Judith Crist commented in her contemporaneous review of the film that the final sequences of the film teach Ben, via ‘his own decision to side with the weak that precipitates the film’s tragic climax, that the weak can betray, that the strong can be shattered and that his last-ditch contention that a cowboy has to be dedicated to something higher than cattle is just another bit of dangerous romanticism’ (Crist, op cit.: 56).  Andrew Patrick Nelson suggests that in this sequence, the film stages a moment of ‘heroic action’ familiar from many Westerns – the ‘last stand’ in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969), for example – ‘but then subverts it’ via the depiction of ‘[t]he pious pacifists, unwilling to fight for their land, [who] are also unable to stomach the measures needed to defend it for them’ (Nelson, op cit.). Nelson concludes that the film is intended ‘to be a strong rebuke of the myth of heroic action’ but that its depiction of ‘the craven religious group’, who asks for violence to be enacted in their name but then rejects it hypocritically, has strong precedent in the form of films such as High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), in which Gary Cooper’s marshal Will Kane is forced to stand alone against outlaw Frank Miller’s gang when the townsfolk he is protecting refuse to help him. In High Noon, of course, this culminates in Will Kane throwing his star to the ground, in a gesture which was echoed by Clint Eastwood’s disgusted abandonment of his police badge at the end of Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). The Culpepper Cattle Co. ends on a shot which deliberately alludes to the denouement of High Noon, Ben’s abandonment of his pistol (and what it represents) being framed in a similar manner to the shots in which Will Kane discards his star. Certainly, Ben’s future is uncertain, and there are a lack of possible alternatives for him, all forms of authority within the film depicted as being corrupt (Thornton Pierce’s greed and his bullying tactics; Culpepper’s lack of willingness to help those in need; the hypocrisy of Green and his group). Andrew Patrick Nelson suggests that in this sequence, the film stages a moment of ‘heroic action’ familiar from many Westerns – the ‘last stand’ in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (George Roy Hill, 1969), for example – ‘but then subverts it’ via the depiction of ‘[t]he pious pacifists, unwilling to fight for their land, [who] are also unable to stomach the measures needed to defend it for them’ (Nelson, op cit.). Nelson concludes that the film is intended ‘to be a strong rebuke of the myth of heroic action’ but that its depiction of ‘the craven religious group’, who asks for violence to be enacted in their name but then rejects it hypocritically, has strong precedent in the form of films such as High Noon (Fred Zinnemann, 1952), in which Gary Cooper’s marshal Will Kane is forced to stand alone against outlaw Frank Miller’s gang when the townsfolk he is protecting refuse to help him. In High Noon, of course, this culminates in Will Kane throwing his star to the ground, in a gesture which was echoed by Clint Eastwood’s disgusted abandonment of his police badge at the end of Don Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). The Culpepper Cattle Co. ends on a shot which deliberately alludes to the denouement of High Noon, Ben’s abandonment of his pistol (and what it represents) being framed in a similar manner to the shots in which Will Kane discards his star. Certainly, Ben’s future is uncertain, and there are a lack of possible alternatives for him, all forms of authority within the film depicted as being corrupt (Thornton Pierce’s greed and his bullying tactics; Culpepper’s lack of willingness to help those in need; the hypocrisy of Green and his group).

Video

Taking up just over 19Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, this 1080p presentation of The Culpepper Cattle Co. uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, and is uncut – with a running time of 92:16 mins. As with many revisionist Westerns (for example, Doc), The Culpepper Cattle Co. is dominated by a sombre palette of browns, tans and greens. This is communicated very well in this presentation, the photography having an authentically dirty, grimy look to it. The presentation has a pleasingly authentically filmlike appearance to it: in some scenes, there are some subtle density fluctuations in the emulsions that are noticeable in areas of ‘dead space’ in the frame (eg, shots of the deep blue sky). Taking up just over 19Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc, this 1080p presentation of The Culpepper Cattle Co. uses the AVC codec. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1, and is uncut – with a running time of 92:16 mins. As with many revisionist Westerns (for example, Doc), The Culpepper Cattle Co. is dominated by a sombre palette of browns, tans and greens. This is communicated very well in this presentation, the photography having an authentically dirty, grimy look to it. The presentation has a pleasingly authentically filmlike appearance to it: in some scenes, there are some subtle density fluctuations in the emulsions that are noticeable in areas of ‘dead space’ in the frame (eg, shots of the deep blue sky).

The presentation offers an incredibly rich level of detail and the structure of 35mm film is preserved by a robust encode. The increase in detail allows the viewer to witness, in one scene, the tear running down Ben’s cheek as a doctor tends to his wounds; this is a detail that was never evident in the film’s previous home video releases. Contrast levels are excellent, with strong, defined midtones and deep, rich blacks offset by balanced highlights. It’s a beautifully shot film, and aside from much of the film being shot at what seems to be magic hour, the light giving a warm glow to the photography, the film features a fair bit of contre-jour photography, silhouettes often framed against a sunrise or sunset; these shots are communicated very nicely here. There’s little damage to the material other than the odd fleck or speck here or there and a notoriously difficult-to-remove vertical line present in a handful of shots, and no harmful digital tinkering evident in the presentation.

Audio

Audio is presented via a LPCM 1.0 mono track. This is rich and deep, with lots of range. It is accompanied by optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing; these are accurate and error free.

Extras

The disc includes:  - A brief, optional introduction by the director Dick Richards (1:25) in which Richards discusses the genesis of the film. - A brief, optional introduction by the director Dick Richards (1:25) in which Richards discusses the genesis of the film.

- An audio commentary with actor Bo Hopkins and film historian C Courtney Joyner. The pair discuss the film’s origins, and Hopkins compares the film with his work for Sam Peckinpah. They discuss the film’s aesthetic and the attempts to capture authenticity in both the mise-en-scène and the film’s narrative. They reflect on the similarities between the story of this film and that of the John Wayne Western The Cowboys (Mark Rydell, 1972). The commentary is thorough and enthusiastic, Hopkins and C Courtney Joyner interacting wonderfully throughout. - ‘Black and White in Colour’ (40:46). Here, in a new interview Dick Richards reflects on his career as a commercial photographer and how this evolved. He discusses his work making commercials, which led to his role as the director of The Culpepper Cattle Co. Richards talks about what he hoped to achieve with the film’s aesthetic, shooting a ‘black and white movie in colour’, the casting and the production. He reveals that Peckinpah was one of the film’s fans. (Interestingly, in counterpoint to this, it’s been suggested elsewhere that Sergio Leone was heavily critical of the film.) It’s an excellent, candid and insightful interview. - Location Photography (0:36). These are mostly colour stills (with one monochrome image included) shot during the production of the film. - Promotional Materials (0:20). This gallery includes headshots and group portraits of the actors, along with lobby cards and posters used to promote the picture. - Original Theatrical Trailer (2:56). - Radio Spot (0:30).

Overall

The Culpepper Cattle Co. is a picture that feels very much of its time, strong parallels existing between it and many of the other revisionist Westerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like a number of those films, such as Ulzana’s Raid or Chato’s Land, The Culpepper Cattle Co. is pretty much essential viewing for anyone who has even a passing interest in revisionist Westerns of that era. It’s a beautifully lensed film, with its story offering an interesting counterpoint to Soldier Blue, in particular. The film’s worldview seems similar in many ways to that expressed within Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, in particular, with the climax offering some interesting parallels with Peckinpah’s most famous Western; in light of this, Richards’ revelation in the extras that Peckinpah was a fan of the film is unsurprising. The Culpepper Cattle Co. is a picture that feels very much of its time, strong parallels existing between it and many of the other revisionist Westerns of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Like a number of those films, such as Ulzana’s Raid or Chato’s Land, The Culpepper Cattle Co. is pretty much essential viewing for anyone who has even a passing interest in revisionist Westerns of that era. It’s a beautifully lensed film, with its story offering an interesting counterpoint to Soldier Blue, in particular. The film’s worldview seems similar in many ways to that expressed within Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, in particular, with the climax offering some interesting parallels with Peckinpah’s most famous Western; in light of this, Richards’ revelation in the extras that Peckinpah was a fan of the film is unsurprising.

This Blu-ray disc contains a stellar presentation of the main feature that is a huge improvement over previous home video releases of the film. (The previous benchmark was the R1 DVD release of the picture, and Signal One Entertainment’s new Blu-ray leaves that release in the proverbial dust.) The main feature is also accompanied by some superb contextual material, the new interview with Richards offering insight into his approach to the film and the commentary with Bo Hopkins situating the film firmly within the context of both the era and the ways in which the Western genre was developing during that period. This is a superb release that fans of Westerns will find to be essential. References: Crist, Judith, 1972: ‘The Stench of the West’. New York Magazine (24 April, 1972): 56-7 French, Philip, 2011: Westerns: Aspects of a Movie Genre. Manchester Carcanet Film (Revised Edition) Lusted, David, 2014: The Western. London: Routledge Nelson, Andrew Patrick, 2015: Still in the Saddle: The Hollywood Western, 1969-1980. University of Oklahoma Press

|

|||||

|