|

|

The Film

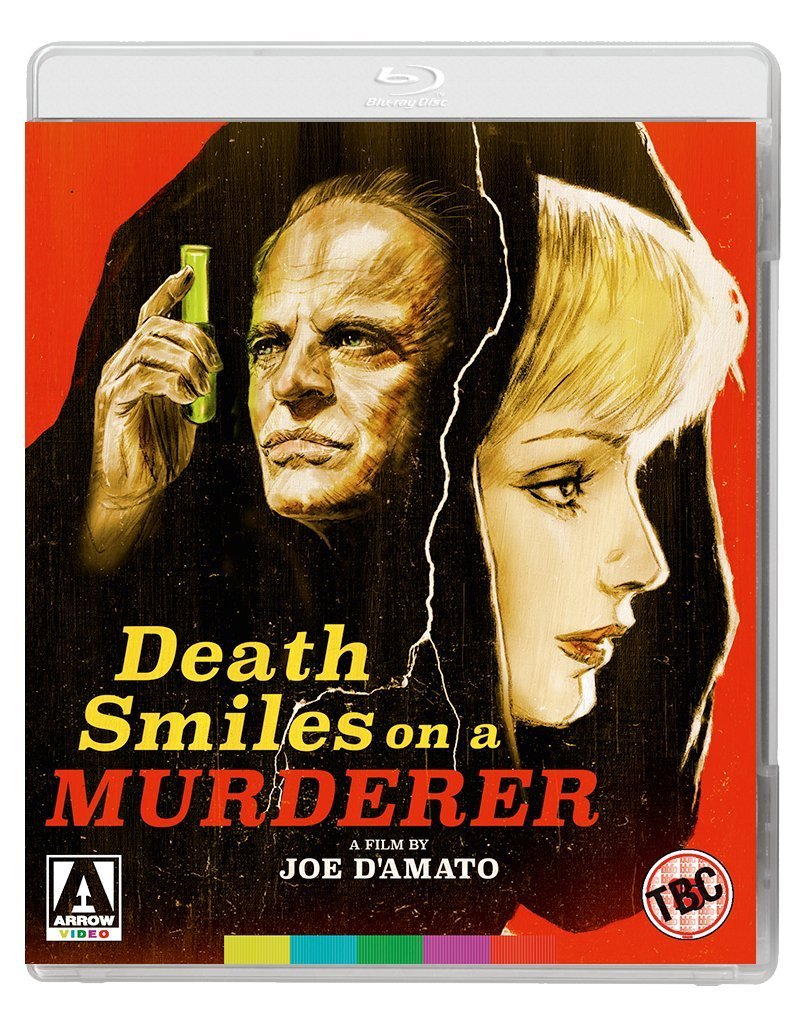

Death Smiles on a Murderer (Aristide Massaccesi, 1973) Death Smiles on a Murderer (Aristide Massaccesi, 1973)

In the early 1900s, following a coach accident which leaves the coach driver graphically impaled on a pole, the female passenger of the coach (Ewa Aulin) is cared for at the nearby home of the von Ravensbruck family, which includes Walter von Ravensbruck (Sergio Doria), his wife Eva (Angela Bo) and their servants Simeon (Marco Mariani) and Gertrude (Carla Mancini). Inspector Dannick (Attilo Dottesio), who is investigating the incident, has suggested that the girl should not be allowed to leave the von Ravensbruck estate. The girl is believed to be suffering from amnesia, but the attending doctor, Sturges (Klaus Kinski), deduces from a pendant around her neck that her name is Greta. Sturges is fascinated with the pendant for another reason, however. He believes it holds the key to eternal life (or perhaps, reanimation of the dead). He conducts strange experiments in his laboratory with his assistant (Pietro Torrisi) and a cellar filled with corpses on ice. Gertrude, who has spied on Sturges as he tested Greta’s resilience to pain by having her undress before poking a sharp needle through her cornea – thus proving to Sturges that Greta is a reanimated corpse – decides to flee from the von Ravensbruck estate but during her escape, an unseen assailant shoots her in the face with a hunting shotgun. Sturges is attacked and garrotted in his laboratory just as his experiments in reviving corpses prove to be successful. Greta and Walter grow close, eventually beginning a passionate sexual relationship. Meanwhile, Eva tries to drown Greta in the bathtub – before seducing her. Greta finds herself involved in a menage a trois with Walter and Eva von Ravensbruck. Driven mad with jealousy, Eva lures Greta to the cellar and bricks her into an alcove. She tells Walter that Greta has left the estate.  The von Ravensbrucks throw a ball. Eva is astonished to find that one of the guests, who has been wearing a mask, reveals herself to be Greta. Eva flees from the ball to the cellar, tearing down the wall she built. However, she finds nothing in the alcove but a cat. Eva flees, seeing Greta – or her ghost. Eva pursues Greta to an upper floor of the house, where Greta confronts Eva, turning into a rotting corpse in front of her eyes. Eva dies, presumably of fear. The von Ravensbrucks throw a ball. Eva is astonished to find that one of the guests, who has been wearing a mask, reveals herself to be Greta. Eva flees from the ball to the cellar, tearing down the wall she built. However, she finds nothing in the alcove but a cat. Eva flees, seeing Greta – or her ghost. Eva pursues Greta to an upper floor of the house, where Greta confronts Eva, turning into a rotting corpse in front of her eyes. Eva dies, presumably of fear.

At Eva’s funeral, Walter’s father (Giacomo Rossi Stuart) pays his respects. Walter’s father left the family home three years earlier, and during a flashback we see that Walter abandoned Greta during childbirth. After the funeral, Greta pursues Walter’s father; he flees and becomes trapped in a crypt. A corpse rises in the crypt, and Walter’s father dies. Walter is left alone, the only surviving von Ravensbruck. Can Inspector Danning solve the case before Walter succumbs to the curse of Greta? A mixture of Gothic horror and thrilling all’italiana (Italian-style thriller) directed by the incredibly prolific Aristide Massaccesi (aka Joe D’Amato), La morte ha sorriso all’assassino is known variously in English as Death Smiles on a Murderer (the title used for this release from Arrow) and Death Smiled at Murder. The film was shot, however, under a different title: 7 strani cadaveri (7 Strange Bodies). Along with the war film Eroi all’inferno (Heroes in Hell, also starring Klaus Kinski), La morte ha sorriso all’assassino was the first feature film on which Massaccesi was credited as director, though he had previously completed a couple of uncredited/pseudonymous directing gigs on films such as the western all’italiana Un bounty killer a Trinita (A Bounty Hunter in Trinity, 1972) and the decamerotico Sollazzevoli storie di mogli gaudenti e mariti penitenti - Decameron nº 69 (More Sexy Canterbury Tales, 1972). Of course, subsequently, Massaccesi would become more commonly known by the pseudonym which he used to sign the majority of his films, ‘Joe D’Amato’.  Like a number of key Italian Gothics, Massaccesi’s film is strangely paced, oscillating between incredibly prolonged scenes and moments of pure delirium. However, the same can be said of many of Massaccesi’s other films: Anthropophagus (The Anthrophagous Beast, 1980), in particular, is a film whose pacing was often criticised by horror fans lured in by the taboo thrills promised by Anthropophagus’ association with the ‘video nasties’ moral panic of the early/mid-1980s. Jim Harper, in Legacy of Blood: A Comprehensive Guide to Slasher Films, notes the two standout gore scenes towards the end of Anthropophagus (one of which, involving Luigi Montefiore’s monster causing a pregnant woman to have a miscarriage before eating the foetus, was infamously presented by the BBC as a clip from a ‘snuff’ movie) and adds that ‘[t]he rest of the film is taken up with lengthy scenes that are either atmospheric or completely dull, depending on your tastes’ (Harper, 2004: 64). Like a number of key Italian Gothics, Massaccesi’s film is strangely paced, oscillating between incredibly prolonged scenes and moments of pure delirium. However, the same can be said of many of Massaccesi’s other films: Anthropophagus (The Anthrophagous Beast, 1980), in particular, is a film whose pacing was often criticised by horror fans lured in by the taboo thrills promised by Anthropophagus’ association with the ‘video nasties’ moral panic of the early/mid-1980s. Jim Harper, in Legacy of Blood: A Comprehensive Guide to Slasher Films, notes the two standout gore scenes towards the end of Anthropophagus (one of which, involving Luigi Montefiore’s monster causing a pregnant woman to have a miscarriage before eating the foetus, was infamously presented by the BBC as a clip from a ‘snuff’ movie) and adds that ‘[t]he rest of the film is taken up with lengthy scenes that are either atmospheric or completely dull, depending on your tastes’ (Harper, 2004: 64).

One of the film’s strengths is the period detail within the mise-en-scène, the film evoking through its aesthetic a strong sense of a period in the past. The narrative takes place in the early 1900s, and the locations, costumes and props all convey a richly-textured bygone era, the attention to detail within the mise-en-scène almost comparable with that of Walerian Borowczyk’s films – from the wooden stethoscope that Kinski uses to check the heartbeat of Greta to the paraphernalia in Dr Sturges’ laboratory. For about a third of its running time, the film intercuts the main narrative with footage of Sturges in his lab, filling test tubes and writing on his blackboard; this material is enigmatic, its purpose largely unclear (other than to expand Kinski’s guest starring part into a more substantial role within the film). The footage is largely redundant, in a narrative sense, functioning as ‘excess’ – but it’s all very atmospheric and moody. This, perhaps, is the essence of Gothic cinema.  Presented in a fairly non-linear way which allows the viewer to decode the mystery as the film progresses, the narrative offers a hodgepodge of ideas from Gothic literature. The basic premise, Greta’s intrusion into the lives of the von Ravensbrucks following a carriage accident outside their home, looks back to Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla, with Sturges bearing some similarities to the unorthodox Dr Hesselius. Sturges’ experiments in his lab, reanimating dead corpses, resembles some elements of H P Lovecraft’s serialised story ‘Herbert West—Reanimator’ (1921-2). Into the main narrative, the script weaves some overt references to other Gothic tales: most obviously, Edgar Allan Poe’s short story ‘The Black Cat’, which is alluded to when Eva von Ravensbruck bricks Greta into an alcove in the basement, only for a cat to exit the tomb when Eva breaks the wall down later. Poe’s ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ is also referenced, when Greta arrives, her identity concealed by an ornate mask, at a ball thrown by the von Ravensbrucks; Greta reveals her identity to Eva, who believes Greta to be dead, resulting in Greta fleeing from the ball and finding her death in the upstairs rooms of the residence. Presented in a fairly non-linear way which allows the viewer to decode the mystery as the film progresses, the narrative offers a hodgepodge of ideas from Gothic literature. The basic premise, Greta’s intrusion into the lives of the von Ravensbrucks following a carriage accident outside their home, looks back to Sheridan Le Fanu’s 1872 novella Carmilla, with Sturges bearing some similarities to the unorthodox Dr Hesselius. Sturges’ experiments in his lab, reanimating dead corpses, resembles some elements of H P Lovecraft’s serialised story ‘Herbert West—Reanimator’ (1921-2). Into the main narrative, the script weaves some overt references to other Gothic tales: most obviously, Edgar Allan Poe’s short story ‘The Black Cat’, which is alluded to when Eva von Ravensbruck bricks Greta into an alcove in the basement, only for a cat to exit the tomb when Eva breaks the wall down later. Poe’s ‘The Masque of the Red Death’ is also referenced, when Greta arrives, her identity concealed by an ornate mask, at a ball thrown by the von Ravensbrucks; Greta reveals her identity to Eva, who believes Greta to be dead, resulting in Greta fleeing from the ball and finding her death in the upstairs rooms of the residence.

Greta functions essentially as a femme fatale, sucking into her destructive orbit the weak-willed and submissive menfolk. However, like many femmes fatale she could be seen as something of an empowered figure, aware of her sexual essence and using it to manipulate both men (Walter) and women (Eva) in pursuit of her goals. In one scene, she speaks with the von Ravensbruck’s talking macaw, Rodolfo, and reflects to Walter that ‘I was looking at all these caged birds, seeing them so joyous, fluttery and chirpy. But are they really? For a moment, I felt a bit like them: imprisoned by someone who’s oppressing me, who’s keeping me chained’. In its depiction of Greta as alternately beautiful/seductive and horrifyingly corpse-like, the film seems self-consciously to foreground the Madonna/Whore dichotomy within the figure of the cinematic femme fatale and its literary, often Gothic, precedents. Certainly, Greta has precedents in Italian Gothic cinema: in Barbara Steele’s dualistic role in Mario Bava’s La maschera del demonio (Mask of Satan/Black Sunday, 1960), for example. The scene in which Greta turns to a hideous ghoul in her lover’s arms is strikingly similar to some of the scenes in Jesus Franco’s contemporaneous witch-hunting film Les demons (1973). The film’s depiction of Greta’s transformation, or the duality that exists within her, predates the events in Room 237 of the Overlook Hotel, captured on film so vividly in Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 film adaptation of The Shining – the room into which Jack Torrance wanders, encountering a beautiful naked woman who, in his embrace, transforms into a desiccated old crone who laughs at Jack’s infidelity.  Greta is motivated by revenge against her lovers. The targets of her revenge are both male and female, the film taking its opportunity to depict Greta’s seduction of both male and female partners/victims in a manner that speaks of the relaxation of film censorship in Italy during the 1960s and throughout the 1970s. The couplings aren’t particularly graphic but feature notable full frontal nudity. The film also emphasises gore, Getrude’s flight from the von Ravensbruck home coming to an end when Gertrude receives a shotgun blast to the face, the camera cutting in to a close-up of the gruesome though not especially ‘realistic’ makeup effects. Elsewhere, an eye is gouged out by a cat, and the coachman is shown with his intestines – presumably the real intestines of an animal – spilling out of his torso. Greta is motivated by revenge against her lovers. The targets of her revenge are both male and female, the film taking its opportunity to depict Greta’s seduction of both male and female partners/victims in a manner that speaks of the relaxation of film censorship in Italy during the 1960s and throughout the 1970s. The couplings aren’t particularly graphic but feature notable full frontal nudity. The film also emphasises gore, Getrude’s flight from the von Ravensbruck home coming to an end when Gertrude receives a shotgun blast to the face, the camera cutting in to a close-up of the gruesome though not especially ‘realistic’ makeup effects. Elsewhere, an eye is gouged out by a cat, and the coachman is shown with his intestines – presumably the real intestines of an animal – spilling out of his torso.

Ultimately, Death Smiles on a Murderer is a moody, atmospheric film, pushing the envelope for the time in terms of gore and nudity, and presenting a narrative that alternates between making complete sense and seemingly completely nonsensical. Then, at the end, everything comes together and the story offers a framework on which all the preceding events may hang – before presenting another, much more confusing, suggestion in its final scene.

Video

The film has been restored in 2k from its original negative and looks absolutely stunning. With a running time of 88:16, Death Smiles on a Murder is presented without cuts. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up 25.2Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended 1.85:1 aspect ratio. The film has been restored in 2k from its original negative and looks absolutely stunning. With a running time of 88:16, Death Smiles on a Murder is presented without cuts. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec and takes up 25.2Gb of space on the Blu-ray disc. The film is presented in its intended 1.85:1 aspect ratio.

The photography makes interesting use of extreme wide-angle lenses to communicate a sense of disorientation – including some mobile wide-angle point-of-view shots. On start-up, the disc presents the viewer the option of watching the film with Italian or English onscreen text and titles. Fine detail is excellent, close-ups offering a rich sense of texture. Contrast levels are equally pleasing, midtones being defined superbly and shadows tapering off to deep black. The presentation offers a beautiful balance of light and dark. Colour is consistent and naturalistic throughout. There is little to no noticeable damage. Finally, a solid encode ensures the presentation retains the structure of 35mm film. Some large screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review, including a visual comparison with the Italian Shock DVD release. Please click them to enlarge.

Audio

The film is presented with the option of the Italian audio track or the English dub. Both audio tracks are presented in LPCM 1.0. The English dub for this picture is actually pretty good. The Italian track is presented with English subtitles translating the Italian dialogue; the English track has accompanying English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing (with are, of course, optional). The audio tracks and subtitles cannot be changed ‘on the fly’: the viewer must return to the disc menus to switch between Italian and English. The film’s score, by Berto Pisano, uses percussion, synthesisers and electric guitars in its main theme to generate a sense of unease. The overall effect is rather like Friedkin’s use of Krzysztof Penderecki’s music in The Exorcist (also 1973). Elsewhere, Pisano builds mournful, romantic themes using more conventional instrumentation (strings, harpsichord and brass). It’s an excellent, Gothic score. Both audio tracks are pleasing in terms of fidelity and clarity. The Italian audio track is a little richer and deeper, but the English track is perfectly acceptable.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An audio commentary with Tim Lucas. This is a typically information dense track from Lucas, who discusses the film’s production and distribution history, discussing its place in the career of Massaccesi. He discusses the film’s narrative, exploring its complexities and areas of confusion. - ‘D’Amato Smiles on Death’ (5:57). In an archival interview from 1999, Massaccesi talks about his association with the film and reflects on why he chose this picture as the first film on which he used his real name. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘All About Ewa’ (42:55). A new interview with Ewa Aulin sees the actress discussing her career, discussing how she became an actress and reflecting on specific films, including this picture and Jorge Grau’s Ceremonia sangrieta. She also talks about her side career singing songs for children’s records, which led to her album Il Valzer Fini. The interview is in Italian, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Smiling on the Taboo’ (21:34). In a new video essay, podcaster Kat Ellinger. There’s some overlap with the Lucas commentary and Ellinger struggles with some of the Italian pronunciation, but Ellinger makes some interesting connections between Massaccesi’s work as a cinematographer and the films he directed. - Trailers: English trailer (2:47); Italian trailer (2:47). - Stills Gallery (7:20).

Overall

Confusing, badly paced and intermittently exploding with moments of gore and sexuality, Death Smiles on a Murderer nevertheless weaves its own strange spell; its ‘flaws’ (its lurching sense of pace, its emphasis on atmosphere over plot, its fascination with sex and terror) are arguably the cornerstones of Gothic fiction, and Massaccesi’s film exploits these mercilessly. Kinski’s role is essentially as a guest star/bit part player, but his screentime is extended ad infinitum by repetitive shots of Dr Sturges working in his lab. It’s a Marmite film that one will either love or hate. This reviewer falls into the former camp, but will happily admit that, like many European Gothics of the 1970s, Massaccesi's film isn't for everyone. Confusing, badly paced and intermittently exploding with moments of gore and sexuality, Death Smiles on a Murderer nevertheless weaves its own strange spell; its ‘flaws’ (its lurching sense of pace, its emphasis on atmosphere over plot, its fascination with sex and terror) are arguably the cornerstones of Gothic fiction, and Massaccesi’s film exploits these mercilessly. Kinski’s role is essentially as a guest star/bit part player, but his screentime is extended ad infinitum by repetitive shots of Dr Sturges working in his lab. It’s a Marmite film that one will either love or hate. This reviewer falls into the former camp, but will happily admit that, like many European Gothics of the 1970s, Massaccesi's film isn't for everyone.

Arrow’s presentation of the film is top-notch. The main feature is presented excellently on this Blu-ray release and is accompanied by some solid contextual material. In particular, the extended interview with Ewa Aulin is a delight, casting this actress’ work in a new light. References: Harper, Jim, 2004: Legacy of Blood: A Comprehensive Guide to Slasher Films. Manchester: Headpress/Critical Vision Please click to enlarge: Italian Shock DVD:

Arrow Video Blu-ray:

Italian Shock DVD:

Arrow Video Blu-ray:

Italian Shock DVD:

Arrow Video Blu-ray:

|

|||||

|