|

|

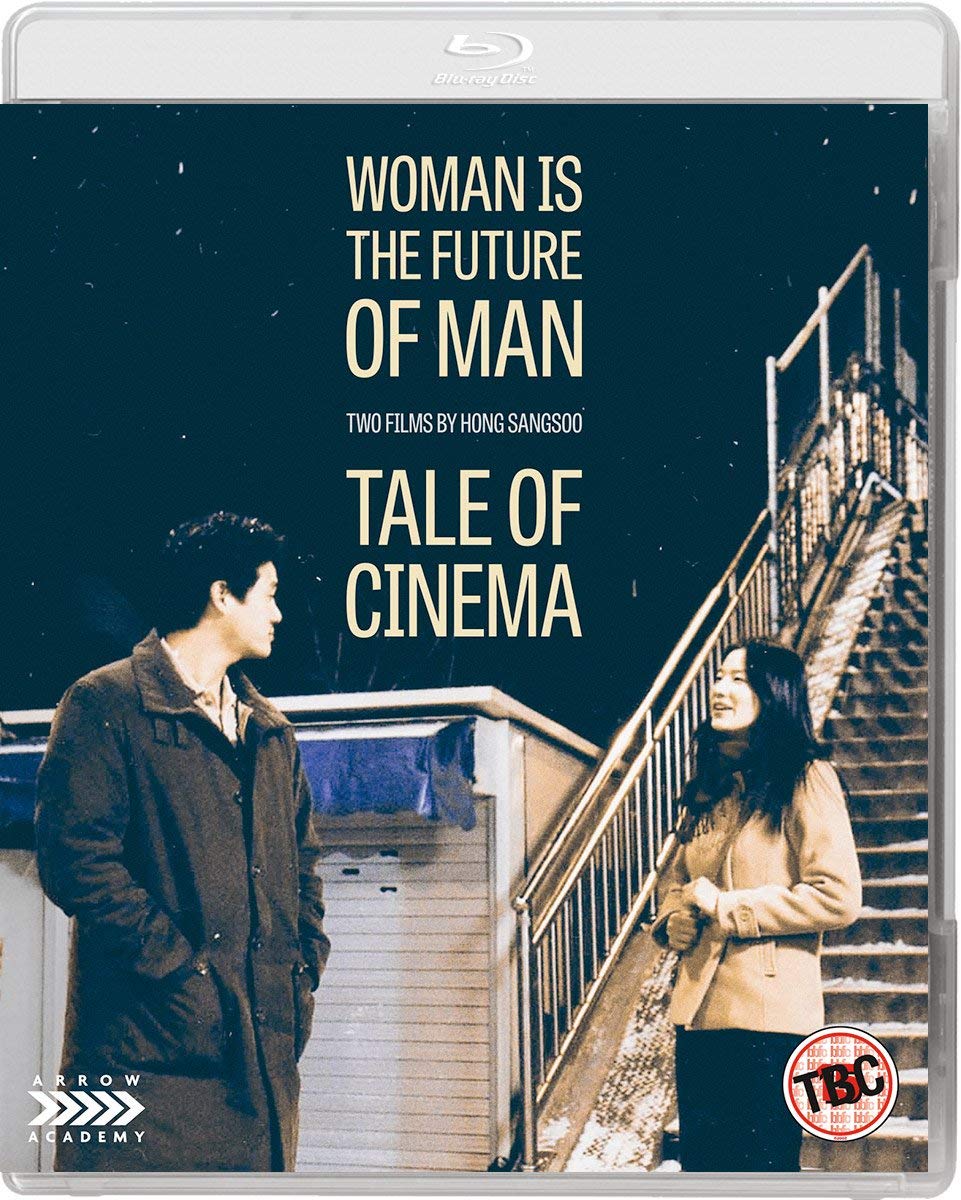

Woman Is the Future of Man AKA Yeojaneun namjaui miraeda (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray ALL - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (29th July 2018). |

|

The Film

Two Films by Sang-soo Hong: Woman is the Future of Man and Tale of Cinema Two Films by Sang-soo Hong contains the fifth and sixth films of South Korean director Sang-soo Hong, Woman is the Future of Man (2004) and Tale of Cinema (2005).  In Woman is the Future of Man, Hyeon-gon Kim (Tae-woo Kim) returns to Korea after studying filmmaking at university in the USA. He is reunited with his old friend, Mun-ho Lee (Ji-tae Yu), who teaches Western art at a local university. Mun-ho lives in an expensive house, presumably mortgaged up to the hilt, and has a wife; but Mun-ho refuses to let Hyeon-gon into his home and does not introduce his old friend to his spouse. Instead, he takes his friend to a cheap restaurant, where they gradually get drunk on soju. After both men are rebuffed by a waitress, they reflect on Hyeon-gon’s old girlfriend Seon-hwa Park (Hyun-Ah Sung), with whom – unbeknownst to Hyeon-gon – Mun-ho also had a fling after Hyeon-gon left Korea to study in America. In Woman is the Future of Man, Hyeon-gon Kim (Tae-woo Kim) returns to Korea after studying filmmaking at university in the USA. He is reunited with his old friend, Mun-ho Lee (Ji-tae Yu), who teaches Western art at a local university. Mun-ho lives in an expensive house, presumably mortgaged up to the hilt, and has a wife; but Mun-ho refuses to let Hyeon-gon into his home and does not introduce his old friend to his spouse. Instead, he takes his friend to a cheap restaurant, where they gradually get drunk on soju. After both men are rebuffed by a waitress, they reflect on Hyeon-gon’s old girlfriend Seon-hwa Park (Hyun-Ah Sung), with whom – unbeknownst to Hyeon-gon – Mun-ho also had a fling after Hyeon-gon left Korea to study in America.

Hyeon-gon and Mun-ho decide to see if they can track down Seon-hwa, who Mun-ho has heard is based in Puchon, having dropped out of university and possibly worked for a while as a prostitute. In Puchon, they find Seon-hwa working in a hotel. The trio go to Seon-hwa’s place, where they drink more soju until a guilt-ridden Hyeon-gon begs Seon-hwa to burn him with a cigarette. She refuses, instead offering him a bed for the night. Mun-ho falls asleep on the sofa. In the middle of the night, Mun-ho awakens and asks Seon-hwa to perform fellatio on him. She does, and the pair retire to another bedroom. In the morning, Seon-hwa vows to take Hyeon-gon and Mun-ho to a hot spring, but on the way Mun-ho encounters some of his students playing football, and he decides to stay with them and talk. At the end of the day, Hyeon-gon and Seon-hwa walk past the football pitch hoping to find Mun-ho, but he has already left. Hyeon-gon storms off and leaves Seon-hwa by herself. That evening, Mun-ho meets with a group of his students. He humiliates a female student by asking her detailed questions about her sex life, before drunkenly berating a male student who attempts to defend her. One of his female students, Kyunghee, follows Mun-ho out of the bar and offers to sleep with him. They go to a hotel, but it’s filthy. Kyunghee begins to perform fellatio on Mun-ho but they are interrupted by a loud banging on the door of their hotel room.  In Tale of Cinema, Sang-won Jeon (Ki-woo Lee) is shown in a disagreement with his older brother, who gives Sang-won 200,000 Won. Sang-won vows to spend all of the money. He passes an optician’s, in which he sees an old schoolfriend, Young-shil Choi (Ji-won Uhm), working. He approaches her and offers to take her out for dinner. She agrees. In Tale of Cinema, Sang-won Jeon (Ki-woo Lee) is shown in a disagreement with his older brother, who gives Sang-won 200,000 Won. Sang-won vows to spend all of the money. He passes an optician’s, in which he sees an old schoolfriend, Young-shil Choi (Ji-won Uhm), working. He approaches her and offers to take her out for dinner. She agrees.

He meets up with Young-shil at the end of her shift, and the pair go drinking. They drink copious amounts of soju, and Young-shil sings karaoke. They end up at a hotel where they make an aborted attempt to have sex, though Sang-won can’t maintain his erection. Young-shil reveals to Sang-won that she left school because one of the teachers was abusing her sexually. They fall asleep, Sang-won dreaming of a strange encounter with a Western girl on the landing of the hotel. When he awakens, he tries once again to have sex with Young-shil but is again unsuccessful. He tells her, ‘I’d like to die. End with a flourish’. She reveals that she too would ‘like to die [….] Let’s die together’. In the morning, they write suicide notes before buying eighty sleeping pills, being careful to purchase them in smaller quantities from different shops. At the hotel, they divide up the sleeping pills. Sang-won begins to take them whilst Young-shil weeps uncontrollably. At night, Young-shil wakes and vomits. She telephones Sang-won’s family, telling them where to find him. She then leaves Sang-won on his own. Sang-won is found by his father, who rushes him to hospital. As Sang-won recuperates, he is admonished by his mother, who mocks his failed suicide attempt and tells him ‘You say it’s my fault you want to die. So go and die’. Sang-won rushes to the roof of the building, in voiceover asserting that ‘Nobody cared’.  In a cinema, a slightly awkward young man, Dong-soo Kim (Sang-kyung Kim), exits a screening room, apparently having watched Sang-won’s story as part of a retrospective of films made by Dong-soo’s university classmate Hyongsu Yi. Out of Dong-soo’s yeargroup, Hyongsu was apparently the only student to progress into a career as a filmmaker. However, Hyongsu is gravely ill, and this is the reason for the retrospective. Hyongsu’s former classmates have arranged a fundraising event for him, and Dong-soo has been invited to this. In a cinema, a slightly awkward young man, Dong-soo Kim (Sang-kyung Kim), exits a screening room, apparently having watched Sang-won’s story as part of a retrospective of films made by Dong-soo’s university classmate Hyongsu Yi. Out of Dong-soo’s yeargroup, Hyongsu was apparently the only student to progress into a career as a filmmaker. However, Hyongsu is gravely ill, and this is the reason for the retrospective. Hyongsu’s former classmates have arranged a fundraising event for him, and Dong-soo has been invited to this.

Dong-soo sees Young-shil, who acted in the film about Sang-won, and follows her to the same opticians in which her character in the film worked. He approaches her; she tells him she is going to the fundraiser too, as the role in Hyongsu’s film was her big break and she has a fondness for the film director. At the fundraiser, Dong-soo is treated coldly by some of his former classmates, who suggest he has a reputation for getting drunk. Afterwards, Dong-soo offers to accompany Young-shil to the hospital, to see Hyongsu. However, before he leaves Dong-soo is told by one of his classmates that Young-shil can’t get work as an actress following her ‘accident’: he claims Young-shil was involved with an artist who, when she tried to leave him, attacked her with a knife, leaving her with scars ‘in intimate places’. After the hospital, Dong-soo and Young-shil go drinking. After many glasses of soju, Dong-soo tells Young-shil that the story of Sang-won was based on his own experiences: Dong-soo tried to take his own life in the same way as Sang-won and told his story to Hyongsu, who used it as the basis for his film. Later, Dong-soo seemingly takes advantage of the desperately drunk Young-shil, taking her to a hotel room and fucking her. He is confused, however, when he discovers that the story about her scars ‘in intimate places’ was a fabrication. Becoming increasingly clingy and desperate, Dong-soo suggests a suicide pact to Young-shil. She declines and leaves him alone. Dong-soo visits the hospital to speak with Hyongsu and, despite being told his condition has improved, finds the filmmaker a wreck. Laid out on a gurney, Hyongsu seems to be in agony and is terrified of dying, begging Dong-soo, ‘It hurts so much. I think I’m going to die [….] I don’t want to die’. In response, Don-soo weeps: ‘It’s my fault’, he says.  Jinhee Choi has suggested that whereas the work of Sang-soo’s two most prominent contemporaries in South Korean cinema, Ki-Duk Kim and Chan-wook Park, may be framed ‘in response to emerging Asia Extreme trends’, Sang-soo’s films ‘can be assessed in light of a different aesthetic trend: Asian Minimalism’ (Choi, 2010: np). Choi compares Sang-soo’s approach to filmmaking with that of Hsiao-hsien Hou’s A City of Sadness (1989), which offers a ‘slowly paced, distanced observation of a personal story’ (ibid.). Sang-soo’s films, Choi offers, ‘are slowly paced via long takes and a static camera’, though Sang-soo’s ‘style does not call attention to itself as much as [Hsiao-hsien] Hou’s or Tsia Ming-liang’s’ (ibid.). Citing David Bordwell, Kyung-tae Kim has also located Sang-soo Hong’s work within the paradigm of ‘Asian minimalism’, alongside Hsiao-hsien Hou, Ming-liang Tsia and the Japanese filmmaker Kore-eda Hirokazu. Like these other filmmakers, Kyung-tae argues, Sang-soo ‘focuses on the everyday, omitting major incidents and background information in favor of an unresolved ambiguity about the characters’ motivations’ (Kyung-tae, 2015: 48). Jinhee Choi has suggested that whereas the work of Sang-soo’s two most prominent contemporaries in South Korean cinema, Ki-Duk Kim and Chan-wook Park, may be framed ‘in response to emerging Asia Extreme trends’, Sang-soo’s films ‘can be assessed in light of a different aesthetic trend: Asian Minimalism’ (Choi, 2010: np). Choi compares Sang-soo’s approach to filmmaking with that of Hsiao-hsien Hou’s A City of Sadness (1989), which offers a ‘slowly paced, distanced observation of a personal story’ (ibid.). Sang-soo’s films, Choi offers, ‘are slowly paced via long takes and a static camera’, though Sang-soo’s ‘style does not call attention to itself as much as [Hsiao-hsien] Hou’s or Tsia Ming-liang’s’ (ibid.). Citing David Bordwell, Kyung-tae Kim has also located Sang-soo Hong’s work within the paradigm of ‘Asian minimalism’, alongside Hsiao-hsien Hou, Ming-liang Tsia and the Japanese filmmaker Kore-eda Hirokazu. Like these other filmmakers, Kyung-tae argues, Sang-soo ‘focuses on the everyday, omitting major incidents and background information in favor of an unresolved ambiguity about the characters’ motivations’ (Kyung-tae, 2015: 48).

From Sang-soo’s debut feature, The Day a Pig Fell into the Well (1996), onwards, Sang-soo has demonstrated a ‘sensitivity to behaviour and gift for language’ that bestows upon his films ‘a vivid (or, perhaps, an enhanced) realism’ (Paquet, 2009: 83). This is countered by a very objective filmmaking style that favours long takes and static compositions: Darcy Paquet has suggested this ‘refusal [by Sang-soo] to emphasise any one aspect of the image or story over another’ leaves viewers ‘labouring to construct meaning out of what they’ see on screen (ibid.).  Another trait of Sang-soo’s cinema, Bert Cardullo argues, is their tendency to ‘overtly or indirectly subvert narrative expectations, in the first place through elliptical editing of dual narratives by placing them, or parts of them, one after the other, such that story A and story B play off each other enigmatically and even abstractly rather than in clearly defined contrasts or carefully arranged juxtapositions’ (Cardullo, 2012: 124). In the case of Woman is the Future of Man, the film juxtaposes the past with the present, but the analepses overlap with the diegetic present to such an extent that it is sometimes difficult to tell where we are, in terms of the temporal setting of specific scenes, other than by decoding objects in the mise-en-scène (in particular, Seon-hwa’s hairstyle). Additionally, there are some fragments of scenes – such as the moment during which Mun-ho watches his students playing football and finds himself the centre of attention of his female students – which seem as if they might be moments of pure fantasy, but which are depicted in a way that neither affirms nor denies their sense of reality (in terms of their relationship with the diegesis of the film itself). (Likewise, Mun-ho tells his friend of his domestic life and his wife, but conspicuously never invites Hyeon-gon into his home, and like Hyeon-gon we never see either the Mun-ho’s wife or the interior of his home – which might lead us to wonder whether Mun-ho is simply presenting a ‘front’ to Hyeon-gon.) In Tale of Cinema, the first half of the film is taken up by the film-within-a-film, the short movie starring Young-shil Choi and revolving around her suicide pact with Sang-won Jeon, before the film segues into the misadventures of Dong-soo Kim, the classmate of the short film’s director upon whose experiences the short movie was based. However, the relationship between these two tiers within the film’s diegesis is rendered ambiguously, with the effect that when Dong-soo reveals that the short film was based on a story he told to his classmate, the viewer might wonder whether or not he is telling the truth – and whether the first half of the film is in fact a document of Young-shil’s experiences; furthermore, Sang-soo’s selfconscious use of the zoom lens throughout both sections of the film lends a sense of unreality to both stories. Another trait of Sang-soo’s cinema, Bert Cardullo argues, is their tendency to ‘overtly or indirectly subvert narrative expectations, in the first place through elliptical editing of dual narratives by placing them, or parts of them, one after the other, such that story A and story B play off each other enigmatically and even abstractly rather than in clearly defined contrasts or carefully arranged juxtapositions’ (Cardullo, 2012: 124). In the case of Woman is the Future of Man, the film juxtaposes the past with the present, but the analepses overlap with the diegetic present to such an extent that it is sometimes difficult to tell where we are, in terms of the temporal setting of specific scenes, other than by decoding objects in the mise-en-scène (in particular, Seon-hwa’s hairstyle). Additionally, there are some fragments of scenes – such as the moment during which Mun-ho watches his students playing football and finds himself the centre of attention of his female students – which seem as if they might be moments of pure fantasy, but which are depicted in a way that neither affirms nor denies their sense of reality (in terms of their relationship with the diegesis of the film itself). (Likewise, Mun-ho tells his friend of his domestic life and his wife, but conspicuously never invites Hyeon-gon into his home, and like Hyeon-gon we never see either the Mun-ho’s wife or the interior of his home – which might lead us to wonder whether Mun-ho is simply presenting a ‘front’ to Hyeon-gon.) In Tale of Cinema, the first half of the film is taken up by the film-within-a-film, the short movie starring Young-shil Choi and revolving around her suicide pact with Sang-won Jeon, before the film segues into the misadventures of Dong-soo Kim, the classmate of the short film’s director upon whose experiences the short movie was based. However, the relationship between these two tiers within the film’s diegesis is rendered ambiguously, with the effect that when Dong-soo reveals that the short film was based on a story he told to his classmate, the viewer might wonder whether or not he is telling the truth – and whether the first half of the film is in fact a document of Young-shil’s experiences; furthermore, Sang-soo’s selfconscious use of the zoom lens throughout both sections of the film lends a sense of unreality to both stories.

Bert Cardullo suggests that the static composition in the scene in which Mun-ho and Hyeon-gon catch up with one another in a restaurant, whilst getting slowly drunk on soju, mirrors the sense of stasis in both characters’ lives (Cardullo, op cit.: 126). Hyeon-gon has returned from the US, where has been studying filmmaking, and has plans to pursue a career as a film director, though there is little evidence that these plans are anything more than a pipe dream (Hyeon-gon doesn’t even have a screenplay to sell) and Mun-ho suggests that seeking a position as a teacher would provide Hyeon-gon with greater stability. Meanwile, Mun-ho lectures in Western art at a university, and he tells Hyeon-gon that his sole dream is to achieve a tenured position; but the manner in which Mun-ho is quick to put down and ridicule his friend suggests that he is deeply unhappy with his own life. Bert Cardullo suggests that the static composition in the scene in which Mun-ho and Hyeon-gon catch up with one another in a restaurant, whilst getting slowly drunk on soju, mirrors the sense of stasis in both characters’ lives (Cardullo, op cit.: 126). Hyeon-gon has returned from the US, where has been studying filmmaking, and has plans to pursue a career as a film director, though there is little evidence that these plans are anything more than a pipe dream (Hyeon-gon doesn’t even have a screenplay to sell) and Mun-ho suggests that seeking a position as a teacher would provide Hyeon-gon with greater stability. Meanwile, Mun-ho lectures in Western art at a university, and he tells Hyeon-gon that his sole dream is to achieve a tenured position; but the manner in which Mun-ho is quick to put down and ridicule his friend suggests that he is deeply unhappy with his own life.

Though both films feature fairly graphic sex scenes, in both Woman is the Future of Man and Tale of Cinema the sex act seems to further alienate the characters rather than bring them together. There are four sex scenes in Woman is the Future of Man. In the first of these, via flashback, Seon-hwa tells Hyeon-gon that she has been raped by an acquaintance who dragged her into a taxi headed to Puchon, where he molested her in a hotel room. Hyeon-gon bathes Seon-hwa, paying particular attention to cleaning her genitals (telling her he will ‘cleanse’ her) before the pair are shown in the act of coitus, Hyeon-gon suggesting almost clinically that he will ‘cleanse’ Seon-hwa through fucking her. Later, in another flashback Mun-ho and Seon-hwa are shown in bed together, after Hyeon-gon has left to study in America, but the sex between them is clumsy and inarticulate, Mun-ho asserting that he didn’t know women shaved their legs and Seon-hwa stopping him mid-flow to ask his permission to moan. The film’s next sex scene takes place after Mun-ho and Hyeon-gon have been reunited with Seon-hwa in the present. Seon-hwa shows Hyeon-gon to one of her bedrooms whilst Mun-ho collapses on the sofa. In the night, Seon-hwa visits Mun-ho and without any foreplay he asks, coldly, if she will ‘suck [him] off’. Seon-hwa obliges, and the pair wander off to another of the bedrooms. Finally, towards the end of the film Mun-ho takes one of his female students to a hotel room; upon arrival, they realise that the room is filthy and infested with critters, to such an extent that Mun-ho says it would be difficult to even sit down – let alone ‘perform’ on the bed. However, Mun-ho, again, asks his student to ‘suck me off’. The student obliges, but they are interrupted by Hyeon-gon, who has followed them to the hotel and bangs on the door of their room.  In Tale of Cinema, Young-shil and Sang-won have sex with one another in the hotel room they have booked, but their attempts at coitus fail miserably: the sex act hurts both of them physically, and Sang-won is, apparently, unable to maintain his erection. Afterwards, they make the decision to commit suicide together. Later, Young-shil is pursued by Dong-soo and eventually agrees to have sex with him. They fuck in a hotel, Young-shil seemingly conceding to this out of boredom rather than because of any attraction to Dong-soo. Afterwards, Young-shil leaves Dong-soo, whose behaviour has become increasingly clingy and bizarre; in an echo of Sang-won’s post-coital outburst in the film-within-a-film, Dong-soo suggests a suicide pact to Young-shil. The sex act has failed to bring them any closer together, and in fact has served simply to reinforce the gulf that exists between them. In Tale of Cinema, Young-shil and Sang-won have sex with one another in the hotel room they have booked, but their attempts at coitus fail miserably: the sex act hurts both of them physically, and Sang-won is, apparently, unable to maintain his erection. Afterwards, they make the decision to commit suicide together. Later, Young-shil is pursued by Dong-soo and eventually agrees to have sex with him. They fuck in a hotel, Young-shil seemingly conceding to this out of boredom rather than because of any attraction to Dong-soo. Afterwards, Young-shil leaves Dong-soo, whose behaviour has become increasingly clingy and bizarre; in an echo of Sang-won’s post-coital outburst in the film-within-a-film, Dong-soo suggests a suicide pact to Young-shil. The sex act has failed to bring them any closer together, and in fact has served simply to reinforce the gulf that exists between them.

In its depiction of Mun-ho and Hyeon-gon’s exploitation (and, ultimately, humiliation) of Seon-hwa in both past and present, Woman is the Future of Man has some strong parallels with the work of American playwright/filmmaker Neil Labute and its focus on sex and power – in particular, Labute’s play In the Company of Men (which Labute himself filmed in 1997), in which two white collar workers devise ways to exploit and humiliate a deaf female colleague. As the narrative of Woman is the Future of Man progresses, it becomes clear that by being in the orbit of Mun-ho and Hyeon-gon, Seon-hwa’s potential for growth has been stunted. It’s clear that when Hyeon-gon left to study in the USA, Mun-ho saw the potential to exploit Seon-hwa’s loneliness for his own sexual gratification. (Even in the present, the married Mun-ho isn’t above asking Seon-hwa or one of his lonely students to fellate him.) Meanwhile, in the present both Hyeon-gon and Mun-ho are rebuffed by a waitress in the restaurant. (They both approach her, separately, in the same way: Hyeon-gon asks if she’d like to act in a film he plans to make; Mun-ho asks if she’d like to pose as a life model, which, he reminds her, would require her to be nude.) This rebuttal seems to cause both to reflect on Seon-hwa, and they make plans to track her down. Seon-hwa, Mun-ho tells Hyeon-gon, seems to be working in Puchon, most likely as a prostitute. On a bender, the pair eventualy find Seon-hwa, and both of them again use her for their own sexual gratification. Near the film’s end, they leave her outside a children’s play area, the framing juxtaposing Seon-hwa with a childish mural of a young girl playing; the connotations, of a young woman’s innocence lost to the sexual exploitation of the men in her life, couldn’t be more obvious. As Seon-hwa asserts at one point in the film, ‘Men are all alike. If you’d simply held me, I could have let myself go [….] You’re all animals’. Both films begin in a fairly unassuming way but subtly escalate, gradually peeling away emotional layers from the characters and revealing beneath them hostility, anxiety and exploitation. Sang-soo shows himself to be a master of nuance, allowing small details to accumulate, and offering subtle repetition of dialogue, gesture and symbol. (For example, in Woman is the Future of Man a red scarf becomes a key element of the mise-en-scène within a number of scenes.) At the centre of both films are sequences in which the characters drink copious amounts of soju, something which – Tony Rayns suggests in the interview on this disc – is depicted as catalysing outbursts that are emotionally raw. Both films explore the expectation of sex from male-female relationships, and Sang-soo seems to depict sex as a form of exploitation and repression.

Video

Both Woman is the Future of Man and Tale of Cinema are included on the same disc. Both films each take up just under 20Gb of space on the disc. Both films were shot on 35mm colour stock and are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. Both films are also presented in the 1.85:1 screen ratio, which would seem to be commensurate with the filmmakers’ intentions. Woman is the Future of Man begins in heavy snow and features some nicely-balanced contrast, the shoulder being protected (the whites of the snow aren’t blown out) and defined midtones giving way to gradation in the toe. Detail is mostly very good, Sang-soo’s tendency to stage scenes in depth being communicated very well on this HD presentation of the film. Colours are stable and consistent, though the palette of the flashbacks is (intentionally) warmer than the palette for the scenes that take place in the diegetic present. The grain structure of 35mm film is present but this varies from scene to scene, sometimes seeming slightly muted. Tale of Cinema features, as noted above, much selfconscious use of zoom lenses. Detail seems lesser than in Woman is the Future of Man and the image is often much more ‘soft’, which may be a result of the zoom lenses used during production, but on the whole the presentation of this film has an appearance which looks slightly more ‘video’ than film-like (in some sequences more than others). Film grain, again, is present but sometimes seems slightly muted, especially in low-light scenes. Woman is the Future of Man

Tale of Cinema

Full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Both films are presented with DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 tracks and DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo tracks. Neither film has a ‘showy’ soundscape, and in the case of both film, both tracks are serviceable, demonstrating good range and depth. In truth, other than some ambient effects, there’s not much between the 5.1 tracks and the stereo tracks. Optional English subtitles are provided for both films. These are easy to read and free from errors.

Extras

The disc includes a set of extras relating to each film (selecting the main feature from the main menu will allow the viewer to watch the extras for that specific picture):  Woman is the Future of Man Woman is the Future of Man

- Introduction by Martin Scorsese (2:32). Scorsese offers a brief, but insightful, introduction to Woman is the Future of Man. - Introduction by Tony Rayns (42:05). Rayns delivers a typically exhaustive overview of the film, beginning by exploring Sang-soo’s career generally before looking in detail at some of the themes and techniques on display in Woman is the Future of Man. Rayns talks about some of the specific cultural references within the film, reflecting on the poor quality of Chinese restaurants in Korea and discussing the significance of soju within Sang-soo’s cinema. - ‘The Making of Woman is the Future of Man’ (38:16). This pieces offers some fascinating behind-the-scenes footage of the production of the film, giving an insight into Sang-soo’s approach as a director. - Interviews with the Actors: Tae-woo Kim (7:47); Hyunah Sun (18:29); Ji-tae Yoo (5:40). The actors’ comments are subtitled in English. These are interesting interviews that focus on Sang-soo’s authorship of the film, the actors reflecting on his approach to filmmaking. - Trailers: Korean Trailer (1:47); Korean Trailer 2 (1:54); French Teaser (056); French Teaser 2 (1:11). - Stills Gallery (1:50).  Tale of Cinema Tale of Cinema

- Introduction by Tony Rayns (20:50). Rayns offers some insightful comments about the film’s themes and Sang-soo’s approach to the material, reflecting on its structure and the relationships between the characters. - Interviews with the Actors: Sang-kyung Kim (14:13); Ji-won Uhm (11:36); Ki-woo Lee (7:05). Again, these interviews are in Korean, with optional English subtitles. As with the interviews accompanying Woman is the Future of Man, the actors focus heavily on Sang-soo’s role as the ‘author’ of this film, discussing his filmmaking techniques and handling of the actors. - Trailers: Korean Trailer (2:30); French Trailer (1:55). - Stills Gallery (11:30).

Overall

Both Woman is the Future of Man and Tale of Cinema are fascinating films. They are slow-burners, each film beginning in a fairly innocuous manner before becoming increasingly caustic. They’re ultimately quite bleak films, leaving the viewer with plenty of food for thought. The structures of both films can be quite ambiguous at times; this is especially true in the case of Tale of Cinema. First-time viewers can expect to be haunted by the questions raised by these films for days after viewing them. Both Woman is the Future of Man and Tale of Cinema are fascinating films. They are slow-burners, each film beginning in a fairly innocuous manner before becoming increasingly caustic. They’re ultimately quite bleak films, leaving the viewer with plenty of food for thought. The structures of both films can be quite ambiguous at times; this is especially true in the case of Tale of Cinema. First-time viewers can expect to be haunted by the questions raised by these films for days after viewing them.

Arrow’s presentations of both films are serviceable enough, certainly an improvement over both films’ previous DVD releases. (The presentations are apparently based on masters that were provided to Arrow by the films’ rightsholders.) The films are accompanied by some excellent contextual material, however, especially the two pieces by Tony Rayns which help to contextualise both pictures. Given the relative scarcity of Sang-soo’s films on home video in the UK, it’s great to see Arrow giving these films such an extras-laden release, hopefully encouraging more viewers to explore the director’s back-catalogue. References: Cardullo, Bert, 2012: World Directors and Their Films: Essays on African, Asian, Latin American, and Middle Eastern Cinema. London: The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Choi, JInhee, 2010: The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Global Perspectives. Wesleyan University Press Kyung-tae, Kim, 2015: K-Movie: The World’s Spotlight on Korean Film. Korean Culture & Information Service Paquet, Darcy, 2009: New Korean Cinema: Breaking the Waves. London: Wallflower Press Please click to enlarge: Woman is the Future of Man

Tale of Cinema

|

|||||

|