|

|

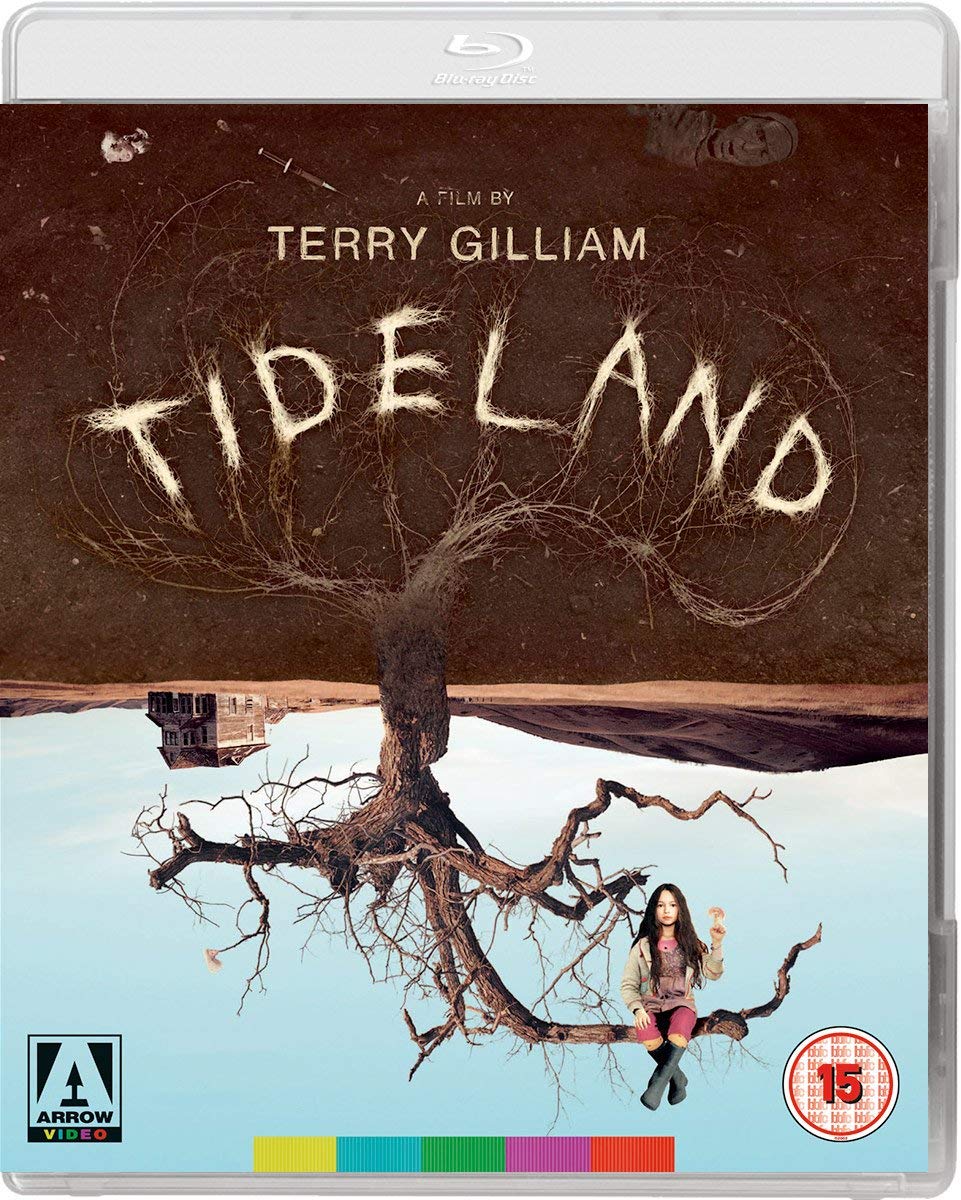

Tideland (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (17th August 2018). |

|

The Film

Tideland (Terry Gilliam, 2005) Tideland (Terry Gilliam, 2005)

Little Jeliza-Rose (Jodelle Ferland) lives with her parents, former rock star Noah (Jeff Bridges) and her bedridden and emotionally unstable mother, who Noah, obsessed with the mythology of Jutland, refers to as ‘Queen Grunhilda’ (Jennifer Tilly). Noah enlists Jeliza-Rose’s help in cooking his heroin before he shoots up and goes ‘on a little vacation’. One night, Jeliza-Rose’s mother dies. Noah becomes convinced that ‘It was the methadone that killed her. Should’a kept her on the junk’. He plans to give her a Viking funeral, surrounding her with her possessions and setting her alight; he is stopped, however, by Jeliza-Rose. Fearing what will happen when the body is discovered, Noah takes Jeliza-Rose on the lam. They travel via bus to an isolated and derelict farmhouse in a cornfield, which Noah claims belonged to his mother. Noah asks Jeliza-Rose to cook a fix of heroin, which Noah then injects. The heroin kills Noah, but Jeliza-Rose is unaware of this and believes her father is simply on his ‘little vacation’. Free from any form of parental supervision, Jeliza-Rose explores the house and plays in the cornfield, hiding in an overturned and burnt-out school bus as an express train roars past on the nearby tracks. She holds conversations with her toys, four severed heads of dolls, a sinister group led by the egotistical Mustique. Entering a cavity in the wall in search of a squirrel she saw sneak through a gap in the roof of the farmhouse, Jeliza-Rose discovers a room filled with her grandmother’s possessions. She dresses in her grandmother’s clothes and places a blonde wig on the corpse of her father, painting his mouth with lipstick.  One day, in the field she sees a woman in black: Dell (Janet McTeer), who was blinded in one eye after being stung by a bee. A practising taxidermist, Dell lives with her childlike brother Dickens (Brendan Fletcher), an epileptic who suffered apparently disastrous brain surgery. Wandering through the cornfields in a snorkel, Dickens lives in a fantasy world in which the fields are underwater and he has a submarine – in reality a bivouac filled with bric-a-brac. Dickens is also convinced that the trains that travel on the line past the corn field are monsters, and he places various objects – ranging from coins to shotgun shells – on the tracks in order to kill the monster (ie, derail the train). One day, in the field she sees a woman in black: Dell (Janet McTeer), who was blinded in one eye after being stung by a bee. A practising taxidermist, Dell lives with her childlike brother Dickens (Brendan Fletcher), an epileptic who suffered apparently disastrous brain surgery. Wandering through the cornfields in a snorkel, Dickens lives in a fantasy world in which the fields are underwater and he has a submarine – in reality a bivouac filled with bric-a-brac. Dickens is also convinced that the trains that travel on the line past the corn field are monsters, and he places various objects – ranging from coins to shotgun shells – on the tracks in order to kill the monster (ie, derail the train).

Dell becomes aware that Jeliza-Rose is Noah’s daughter. Dell visits the farmhouse with Dickens, and together they embalm Noah’s corpse: Dell was in love with Noah before he left the area to become a musician. Jeliza-Rose lives with her father’s mummified corpse, and she is drawn closer to Dickens until, one day, Dickens reveals to her dynamite that he has stolen from the nearby quarry and with which he plans to kill the ‘monster’. Tideland opens in a cornfield in which Jeliza-Rose plays with her dolls; the cornfield sits next to the derelict farmhouse to which she has been brought by her father, Noah. The imagery of this opening sequence and the child’s perspective on the narrative invite comparisons with Philip Ridley’s 1990 film The Reflecting Skin (the Soda Pictures Blu-ray release of The Reflecting Skin has been reviewed by us here): like Seth Dove in that picture, Jeliza-Rose – from whose perspective Tideland is told – is an unreliable filter for the narrative, her misperceptions and flights of imagination leading the film into the realm of magical realism. The combination of this imagery and Jeliza-Rose’s Southern US accent, as she delivers offscreen narration which is based on Alice’s encounter with the rabbit hole in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adentures in Wonderland, might also remind viewers of the introduction of Linda Manz’s narration in the opening moments of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978). Inspired by her love of Lewis Carroll, Jeliza-Rose creates a world for herself which is filled with anthropomorphic animals and other unnatural delights. Kathryn Laity has also highlighted some of the similarities between Tideland and Guillermo del Toro’s roughly contemporaneous Pan’s Labyrinth (2006): in particular, Laity suggests, both films ‘realise […] in [their respective heroines] the Hobbesian potential of the unsupervised child’ and use the image of ‘the gnarled tree that anchors both films’ to ‘embody the decrepitude of age, which seeks to abuse the child – a rotting corpse poised over the innocent body of the child’ (Laity, 2013: 119).  The film’s intimations of the sexual abuse and exploitation of children are subtle and accumulate as the narrative develops. Towards the end of the film, Jeliza-Rose and Dickens kiss on the lips, an action which for Jeliza-Rose mimics the behaviour she has seen of adults. Playfully and delighted, Dickens tells her that they are now ‘silly kissers’, informing Jeliza-Rose that as a child, he used to visit her grandmother when she was alive and they would sometimes kiss for long periods of time, Jeliza-Rose’s grandmother working her tongue into the young Dickens’ mouth. Jeliza-Rose becomes obsessed with the idea that by kissing her, Dickens has given her a baby. As things begin to escalate uncomfortably in Dell and Dickens’ home, Jeliza-Rose and Dickens are interrupted by Dell, who accuses them of having a similar relationship to her (presumably highly lustful) relationship with Noah. Certainly, it’s a challenging film in many ways – not just in its exploration of this particular theme – and in his autobiography, Gilliam noted that ‘we lost the sympathy of half the audience’ in the scene in which Noah asks Jeliza-Rose to prepare his hit of heroin before he injects it (Gilliam, 2015: np). Gilliam notes that ‘We had an ex-junkie who was on methadone to advise us [about such scenes], and we knew we’d got that right when he said, “Oh, fuck! That looks good”’ (ibid.). The film’s intimations of the sexual abuse and exploitation of children are subtle and accumulate as the narrative develops. Towards the end of the film, Jeliza-Rose and Dickens kiss on the lips, an action which for Jeliza-Rose mimics the behaviour she has seen of adults. Playfully and delighted, Dickens tells her that they are now ‘silly kissers’, informing Jeliza-Rose that as a child, he used to visit her grandmother when she was alive and they would sometimes kiss for long periods of time, Jeliza-Rose’s grandmother working her tongue into the young Dickens’ mouth. Jeliza-Rose becomes obsessed with the idea that by kissing her, Dickens has given her a baby. As things begin to escalate uncomfortably in Dell and Dickens’ home, Jeliza-Rose and Dickens are interrupted by Dell, who accuses them of having a similar relationship to her (presumably highly lustful) relationship with Noah. Certainly, it’s a challenging film in many ways – not just in its exploration of this particular theme – and in his autobiography, Gilliam noted that ‘we lost the sympathy of half the audience’ in the scene in which Noah asks Jeliza-Rose to prepare his hit of heroin before he injects it (Gilliam, 2015: np). Gilliam notes that ‘We had an ex-junkie who was on methadone to advise us [about such scenes], and we knew we’d got that right when he said, “Oh, fuck! That looks good”’ (ibid.).

Tideland was quite ill-received upon its initial release in 2005. Gilliam’s introduction to the picture on this disc offers a subtle kick to the film’s staunch critics, Gilliam suggesting that in order to comprehend the picture, one must watch it as if through the eyes of a child. This might seem to be a ‘cop out’, but nevertheless like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, The Reflecting Skin and Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951), the film constructs a world entirely filtered through the perspective of a child/youth, and as Gilliam notes in his introduction, children see and comprehend the world differently to adults. (Gilliam also suggests that when he made the film as a 64 year old man, he realised that he saw the world as a young girl; it’s a comment that might cause subtle consternation amongst those offended by Gilliam’s recent tongue-in-cheek comment that he ‘tell[s] the world now I’m a black lesbian’; Gilliam, quoted in Guardian Film, 2018: np.)  Like most, if not all, of Gilliam’s films, Tideland focuses on an unreliable protagonist through whom the narrative events are focalised – and hence the film shares the fantastical viewpoint of its central character. Like many of Gilliam’s protagonists, Jeliza-Rose retreats into the fantastical in response to how horrific her immediate reality is. The theme of someone trapped in a form of stasis recurs throughout the film: Jeliza-Rose’s grandmother’s house is a form of limbo from which the only way out seems to be via the train that roars past the cornfield (and which Dickens, convinced the train is a monster, continuously tries to derail). This theme is introduced early in the film, prior to the death of Jeliza-Rose’s mother, when Noah wakes Jeliza-Rose in the middle of the night to show her a photograph of Tollund Man, one of the bog people discovered in Jutland, telling her to ‘Look at him. He’s just lying there, waiting to come back to life’. Shortly afterwards, following their arrival at Noah’s mother’s farmhouse, Noah asks Jeliza-Rose to prepare his heroin and then takes a hit that kills him. (Jeliza-Rose isn’t aware of this, however, and the body begins to bloat and swell, emitting gases that Jeliza-Rose believes are simply farts.) When Dell discovers that Noah, her former lover, is dead, she embalms the body; the resultant mummy looks strikingly similar to the bog people such as Tollund Man and Grauballe Man. Like most, if not all, of Gilliam’s films, Tideland focuses on an unreliable protagonist through whom the narrative events are focalised – and hence the film shares the fantastical viewpoint of its central character. Like many of Gilliam’s protagonists, Jeliza-Rose retreats into the fantastical in response to how horrific her immediate reality is. The theme of someone trapped in a form of stasis recurs throughout the film: Jeliza-Rose’s grandmother’s house is a form of limbo from which the only way out seems to be via the train that roars past the cornfield (and which Dickens, convinced the train is a monster, continuously tries to derail). This theme is introduced early in the film, prior to the death of Jeliza-Rose’s mother, when Noah wakes Jeliza-Rose in the middle of the night to show her a photograph of Tollund Man, one of the bog people discovered in Jutland, telling her to ‘Look at him. He’s just lying there, waiting to come back to life’. Shortly afterwards, following their arrival at Noah’s mother’s farmhouse, Noah asks Jeliza-Rose to prepare his heroin and then takes a hit that kills him. (Jeliza-Rose isn’t aware of this, however, and the body begins to bloat and swell, emitting gases that Jeliza-Rose believes are simply farts.) When Dell discovers that Noah, her former lover, is dead, she embalms the body; the resultant mummy looks strikingly similar to the bog people such as Tollund Man and Grauballe Man.

Video

Tideland is presented in the 2.35:1 ratio, the ratio at which the film was shown in cinemas. The film was shot in Super 35, however, and some previous DVD releases of the picture presented the film in a slightly ‘opened up’ 1.75:1 ratio. (Gilliam has gone on record stating that his preferred ratio for the film’s home video presentations is 2.25:1.) The film is uncut, running for 120:26 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec. Tideland is presented in the 2.35:1 ratio, the ratio at which the film was shown in cinemas. The film was shot in Super 35, however, and some previous DVD releases of the picture presented the film in a slightly ‘opened up’ 1.75:1 ratio. (Gilliam has gone on record stating that his preferred ratio for the film’s home video presentations is 2.25:1.) The film is uncut, running for 120:26 mins. The 1080p presentation uses the AVC codec.

The master was provided to Arrow by Universal. A 2k digital intermediate was created for the film’s theatrical release, and it seems reasonable to assume that this presentation is based on that digital source. The film looks quite pleasing on this Blu-ray release, detail being handled very well within the presentation – including fine detail in close-ups and the depth within the shots of the cornfield. External sequences feature some harsh sunlight, and contrast levels within this presentation carry these sequences nicely and offer equally pleasing representation of the interior and low-light scenes: midtones are balanced very well and there’s a subtle gradation into the toe. Colours are consistent though not naturalistic – and this is in keeping with the intentions of the filmmakers, who manipulate the palette throughout the film, creating a strange and hallucinatory visual texture for the film. Some scenes seem to suffer from slight edge enhancement and haloing, and other scenes feature a muted grain structure that suggests some digital noise reduction is interfering very slightly with the picture, but in sum it’s a pleasing HD presentation of Tideland. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Please click to enlarge them.

Audio

Audio is presented via a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track. This is rich and makes very effective use of sound separation to create a disquieting ambience. The track is free from distortion; dialogue is audible; and there’s a sense of depth to the audio that is pleasing. Optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing are included. These are easy to read and accurate, though sometimes abbreviate the spoken dialogue for the purposes of fitting it on the screen.

Extras

The disc includes: The disc includes:

- An optional introduction by Terry Gilliam (1:08) in which, shot in stark monochrome, the director admits that the film is divisive and implores the viewer to watch the film with the eyes of a child. - Audio commentary with Terry Gilliam and Tony Grisoni. The pair – director and screenwriter – are on fine form, joking with each other and offering vivid discussion of their love of Mitch Cullin’s novel. They discuss the themes of the film and Gilliam reflects on his approach to directing the film, juxtaposing the beauty of the cornfield with the decay of the interior of the farmhouse. - ‘Getting Gilliam’ (44:46) is a 2005 documentary about the making of Tideland that is directed by Vincenzo Natale. Natale narrates, and the documentary begins with footage of Gilliam pissing into a stream, which may or may not be intended to be symbolic. The documentary offers something of a retrospective of Gilliam’s career to the point of Tideland’s production, also showcasing Gilliam as he speaks about his influences in art and literature. It’s a fascinating documentary, containing plentiful behind-the-scenes footage from the preproduction phase to the production of the film. - ‘The Making of Tideland’ (5:26) is a more conventional archival ‘puff piece’ which features some interviews with members of the cast, author Mitch Cullin (on whose novel the film is based) and Gilliam himself. It’s interesting enough but it’s something of a comedown after Natale’s documentary. - ‘Filming Green Screen’ (3:13). Gilliam narrates over some of the film’s SFX shots, explaining how they were achieved through the magic of green screen technology.

- Deleted Scenes (5:59). This montage of footage cut form the film, presented here in timecoded form, is narrated by Gilliam, who explains where the footage would have appeared in the picture and explains the function of the scenes and why they were omitted. - Interviews: Terry Gilliam (14:30); Jeremy Thomas (9:33); Jeff Bridges, Jodelle Ferland and Jennifer Tilly (4:59). Gilliam talks about the film’s relationship with fairy tales, and reinforces the notion that fairy tales should be frightening to children. He reflects on some of the film’s themes and talks about the origins of some of the imagery and ideas in the film. Producer Jeremy Thomas discusses his relationship with Gilliam and talks about his role in the making of the film. Interviewed separately, the actors talk about being directed by Gilliam, their characters and some of the symbolism in the film. - B-Roll Footage (20:35). This footage seems more like B-roll footage from Natale’s documentary than the main feature, offering behind-the-scenes glimpses of the production of the picture. - Gallery (2:01). A slideshow of images, some presented in typical 2:3 ratio and others in a wider panoramic ratio (which makes me wonder if they might have been shot on set by Bridges with his beloved Widelux camera) are accompanied by the film’s score. - Trailer (1:54).

Overall

In some respects, Tideland feels like Gilliam revisiting some of the themes of his earlier picture Time Bandits: the child’s perspective on the foibles of the adult world; the magical realism of the world the child-protagonist conjures for herself. As in Gilliam’s other films, Gilliam mixes the subtle with a sledgehammer-like approach (graffiti on the wall of Noah’s mother’s farmhouse reads simply, ‘Fuckin’ Shithole’), and there are some bravura moments of animation – such as when the head of Mustique is shown on the body of a woman, a brain being lowered into the cranial cavity of the doll’s head. As the narrative progresses, the combative themes and apocalyptic rhetoric accumulate. Certainly, it’s a love-it-or-hate-it proposition, but however one feels about the film, it lingers in the mind. In some respects, Tideland feels like Gilliam revisiting some of the themes of his earlier picture Time Bandits: the child’s perspective on the foibles of the adult world; the magical realism of the world the child-protagonist conjures for herself. As in Gilliam’s other films, Gilliam mixes the subtle with a sledgehammer-like approach (graffiti on the wall of Noah’s mother’s farmhouse reads simply, ‘Fuckin’ Shithole’), and there are some bravura moments of animation – such as when the head of Mustique is shown on the body of a woman, a brain being lowered into the cranial cavity of the doll’s head. As the narrative progresses, the combative themes and apocalyptic rhetoric accumulate. Certainly, it’s a love-it-or-hate-it proposition, but however one feels about the film, it lingers in the mind.

Arrow’s Blu-ray presentation of the film is very good. There may be some very slight controversy about the aspect ratio (should it be 2.35:1, as per the film’s theatrical release, or 2.25:1, as per Gilliam’s comments around the time of the film’s initial DVD release/s) and there seems to be some fairly minor evidence of digital filtering in the master provided for this release. Nevertheless, it’s a major improvement over the film’s DVD releases, and the main feature is accompanied by some excellent contextual material – highlights of which are the documentary by Vincenzo Natale and the lively commentary track with Gilliam and Tony Grisoni. References: Gilliam, Terry, 2015: Gilliamesque: A Pre-Posthumous Memoir. Canongate Books Guardian Film, 2018: ‘Terry Gilliam on diversity: “I tell the world now I’m a black lesbian”’. [Online.] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/jul/04/terry-gilliam-on-diversity-bbc-monty-python-black-lesbian Laity, Kathryn A, 2013: ‘“Won’t somebody please think of the children?”: The Case for Terry Gilliam’s Tideland’. In: Birkenstein, Jeff et al (eds), 2013: The Cinema of Terry Gilliam: It’s a Mad World. London: Wallflower Press: 118-29 Please click to enlarge:

|

|||||

|