|

|

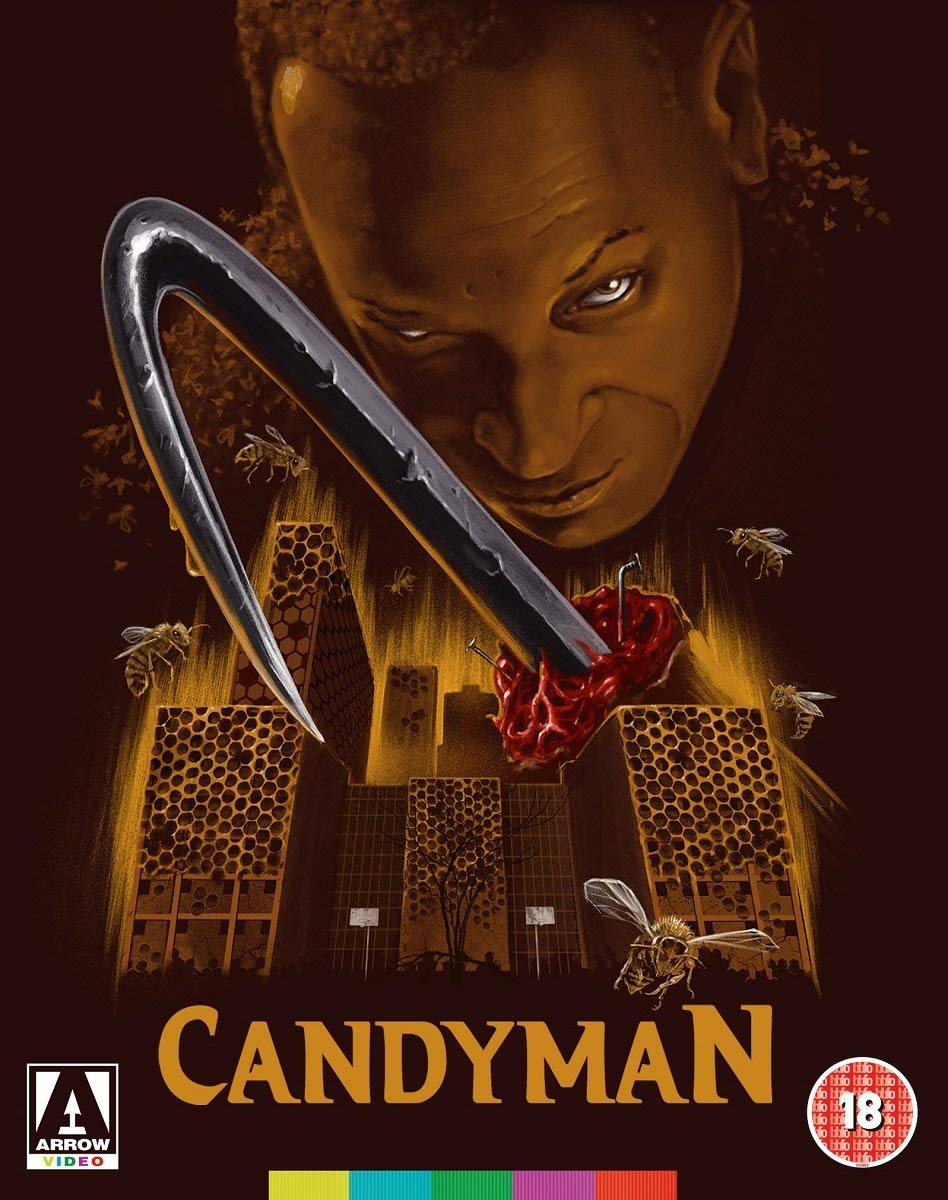

Candyman AKA Clive Barker's Candyman (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (11th November 2018). |

|

The Film

Candyman (Bernard Rose, 1992) Candyman (Bernard Rose, 1992)

Graduate students Helen Lyle (Virginia Madsen) and Bernadette Walsh (Kasi Lemmons) are researching their thesis on urban myths and oral folklore by interviewing freshman students about terrifying stories they believe to be true. During one of these interviews, Helen is told by a freshman about the murders of a young couple, Clara (Marianna Elliott) and Billy (Ted Raimi), which occurred after Clara said the name ‘Candyman’ five times in front of a mirror – an action which, it is said, calls the Candyman (Tony Todd), a supernatural being with a hook for a hand. It is while Helen is transcribing an audio recording of this interview in a classroom at the university that Henrietta (Barbara Alston), one of the university’s cleaners, overhears it. Henrietta and her colleague, Kitty (Sarina C Grant), tell Helen of the murder of a black woman, Ruthie Jean, in the Cabrini-Green housing complex. Ruthie Jean, they say, was killed by the Candyman. Helen investigates this by studying microfiche copies of the city newspaper. Finding confirmation of Ruthie Jean’s murder, Helen railroads Bernadette into accompanying her on a field trip to Cabrini-Green. Visiting Cabrini-Green, Helen and Bernadette discover curious graffiti – apparently depictions of the Candyman, with the phrase ‘Sweets to the Sweet’ recurring. There, Helen and Bernadette meet Anne-Marie (Vanessa Williams), Ruthie Jean’s neighbour and mother to a baby. Meanwhile, Helen suspects her husband Trevor (Xander Berkeley), a lecturer at the university, may be conducting an affair with one of his students. Her research also leads her to the realisation that the high rise in which she and Trevor live was built as a housing project identical to Cabrini-Green but was sold off by the city as expensive condominium apartments. She reveals this to Bernadette, showing Bernie that the bathroom cabinet can be removed, revealing a cavity behind it that allows passage from one apartment to another. Helen speculates that if Cabrini-Green is constructed in the same way, this may be how Ruthie Jean’s murderer/s gained access to her apartment. Replacing the bathroom cabinet in her apartment, Helen cannot resist saying ‘Candyman’ five times in front of the mirror…  Helen and Trevor go to dinner with another lecturer, Philip Purcell (Michael Culkin), who tells Helen that the story of the Candyman has its roots in the lynching of the son of a freed slave in the 1890s. The Candyman was a portrait artist who fell in love with the daughter of a landowner. When she fell pregnant, her father became incensed at his daughter’s relationship with a black man; he hired thugs who sawed off the Candyman’s hand and smeared him in honeycomb taken from a beehive that they had demolished. The Candyman was stung to death, his body burnt and the ashes scattered over the area where Cabrini-Green now stands. Helen and Trevor go to dinner with another lecturer, Philip Purcell (Michael Culkin), who tells Helen that the story of the Candyman has its roots in the lynching of the son of a freed slave in the 1890s. The Candyman was a portrait artist who fell in love with the daughter of a landowner. When she fell pregnant, her father became incensed at his daughter’s relationship with a black man; he hired thugs who sawed off the Candyman’s hand and smeared him in honeycomb taken from a beehive that they had demolished. The Candyman was stung to death, his body burnt and the ashes scattered over the area where Cabrini-Green now stands.

Returning to Cabrini-Green, Helen is led by a young boy, Jake (DeJuan Guy), to a public lavatory building where another boy was murdered. Whilst there, Helen is attacked by a group of young men – one of whom carries a hook in homage to the Candyman. Later, Helen identifies her assailant in a police lineup, and it seems that the Candyman is nothing more than a young punk with a flair for dressing up. It seems that Helen’s thesis may be published, and she is joyful. However, the Candyman (Tony Todd) appears to her, placing her in a trance. When Helen comes to, she is in Anne-Marie’s apartment. Anne-Marie is screaming, her dog butchered and her baby missing; covered in blood, Helen seems the most likely suspect, and she is arrested by the police. The Candyman begins a game of catch and release with Helen, placing her at the centre of a number of violent murders – with the dual aim of reigniting belief in his mythos and drawing Helen, who is seemingly the reincarnation of his lover, into his web.  Based on Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’, published in the Books of Blood, Bernard Rose’s Candyman transposes Barker’s story, set in a run-down council estate in Liverpool, to Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing complex. In Barker’s short story, the protagonist, Helen, is a student who is writing her dissertation on graffiti (‘Graffiti: The Semiotics of Urban Despair’). The estate, the Spector Street Estate, had been built as a symbol of hope but, like many such council estates in England, had become dilapidated and vandalised. Whilst researching her dissertation, Helen becomes fascinated by the urban myth of the ‘Candyman’ and the relationship between this and a number of murders that may or may not have taken place on the estate. The story builds to a ritualistic scene of sacrifice and redemption through fire that is in some ways reminiscent of the climax of Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). Based on Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’, published in the Books of Blood, Bernard Rose’s Candyman transposes Barker’s story, set in a run-down council estate in Liverpool, to Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing complex. In Barker’s short story, the protagonist, Helen, is a student who is writing her dissertation on graffiti (‘Graffiti: The Semiotics of Urban Despair’). The estate, the Spector Street Estate, had been built as a symbol of hope but, like many such council estates in England, had become dilapidated and vandalised. Whilst researching her dissertation, Helen becomes fascinated by the urban myth of the ‘Candyman’ and the relationship between this and a number of murders that may or may not have taken place on the estate. The story builds to a ritualistic scene of sacrifice and redemption through fire that is in some ways reminiscent of the climax of Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973).

As the film opens, Helen is interviewing freshman students about urban legends – though her subjects don’t know the stories they are telling are simply modern myths, believing them to be, in the words of one of the interviewees, ‘totally true’. In the story about the Candyman that piques Helen’s interest, the Candyman slaughters two privileged white teenagers from the suburbs – a far cry, in both setting and victimology, from the murder of Ruthie Jean in Cabrini-Green. This opening sequence, with its visual depiction of the urban legend being told to Helen by a freshman student (in which a young couple – babysitter Claire and her lover Billy – are murdered by the Candyman), references the paradigms of ‘slasher’ movies: as part of Claire’s seduction of Billy, she tells him the story of the Candyman, and as a dare, the pair look into a mirror and recite the Candyman’s name four times. However, they stop before saying his name once more, Claire telling Billy that no-one makes it past the fourth time. Billy goes downstairs to wait for Claire, but before she joins him she looks in the mirror and says ‘Candyman’ again; in the room below, Billy hears her piercing scream and sees a pool of blood form on the ceiling above him.  The dramatic onscreen deaths of this couple, framed as a typical episode from a ‘slasher’ film in which young people are ‘punished’ for contemplating premarital sex, are juxtaposed with the murder of Ruthie Jean, overlooked and neglected by the authorities; Ruthie Jean’s murder, in a housing complex overrun by street gangs and dealers, seems all too recognisable as an incident with corollaries in the real world – in comparison with the ‘slasher’ movie stylings of the deaths of Claire and Billy. Framed in this way, Helen believes the stories about the Candyman are propagated simply to keep people away from Cabrini-Green and to keep its residents in line: the mythos of the Candyman serves to aid the gangs that dominate the housing estate. (‘We’ve got a real shot here, Bernadette’, Helen tells her friend, ‘An entire community starts attributing the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure’.) The film contrasts the white and privileged with the black and impoverished: Helen becomes aware that the apartment complex in which she lives was built at the same time as Cabrini-Green and to the same specifications, but was given an extra spit and polish by the city and sold off as expensive condominium apartments. In the Chicago of Candyman, being black is an index of poverty: aside from the inhabitants of Cabrini-Green and the Candyman himself, two of the three black characters who have lines of dialogue are Henrietta and Kitty, cleaners at the university. (It is Henrietta and Kitty who tell Helen of the death of Ruthie Jean after overhearing Helen transcribing her interview with the freshman student who tells her about Claire and Billy’s death; this trail of information leads to Helen’s decision to investigate Cabrini-Green.) Helen’s black friend Bernadette is the go-between – ethnically similar to the inhabitants of Cabrini-Green but culturally similar to Helen (in their shared status as PhD students). However, Bernadette has a greater sense of the potential dangers of Cabrini-Green and is reluctant to accompany Helen there. (‘Helen, this is sick. This isn’t one of your fairytales’, Bernadette tells Helen, adding that ‘I wouldn’t even drive past there. Heard a kid got shot there the other day’. ‘Every day’, Helen corrects her.) That Helen is a cultural ‘tourist’ who is implicitly exploiting the tragedies of Cabrini-Green for her own gain is foregrounded when Helen and Bernie meet Anne-Marie for the first time, Anne-Marie reminding Helen that ‘whites don’t come here except to give us a problem’; these are words which will resonate when Anne-Marie’s baby is stolen by the Candyman, after Helen ‘calls’ him by saying his name five times in front of her bathroom mirror. ‘What you want to study?’, Anne-Marie asks, ‘That we’re bad? We steal? We gangbang?’ The dramatic onscreen deaths of this couple, framed as a typical episode from a ‘slasher’ film in which young people are ‘punished’ for contemplating premarital sex, are juxtaposed with the murder of Ruthie Jean, overlooked and neglected by the authorities; Ruthie Jean’s murder, in a housing complex overrun by street gangs and dealers, seems all too recognisable as an incident with corollaries in the real world – in comparison with the ‘slasher’ movie stylings of the deaths of Claire and Billy. Framed in this way, Helen believes the stories about the Candyman are propagated simply to keep people away from Cabrini-Green and to keep its residents in line: the mythos of the Candyman serves to aid the gangs that dominate the housing estate. (‘We’ve got a real shot here, Bernadette’, Helen tells her friend, ‘An entire community starts attributing the daily horrors of their lives to a mythical figure’.) The film contrasts the white and privileged with the black and impoverished: Helen becomes aware that the apartment complex in which she lives was built at the same time as Cabrini-Green and to the same specifications, but was given an extra spit and polish by the city and sold off as expensive condominium apartments. In the Chicago of Candyman, being black is an index of poverty: aside from the inhabitants of Cabrini-Green and the Candyman himself, two of the three black characters who have lines of dialogue are Henrietta and Kitty, cleaners at the university. (It is Henrietta and Kitty who tell Helen of the death of Ruthie Jean after overhearing Helen transcribing her interview with the freshman student who tells her about Claire and Billy’s death; this trail of information leads to Helen’s decision to investigate Cabrini-Green.) Helen’s black friend Bernadette is the go-between – ethnically similar to the inhabitants of Cabrini-Green but culturally similar to Helen (in their shared status as PhD students). However, Bernadette has a greater sense of the potential dangers of Cabrini-Green and is reluctant to accompany Helen there. (‘Helen, this is sick. This isn’t one of your fairytales’, Bernadette tells Helen, adding that ‘I wouldn’t even drive past there. Heard a kid got shot there the other day’. ‘Every day’, Helen corrects her.) That Helen is a cultural ‘tourist’ who is implicitly exploiting the tragedies of Cabrini-Green for her own gain is foregrounded when Helen and Bernie meet Anne-Marie for the first time, Anne-Marie reminding Helen that ‘whites don’t come here except to give us a problem’; these are words which will resonate when Anne-Marie’s baby is stolen by the Candyman, after Helen ‘calls’ him by saying his name five times in front of her bathroom mirror. ‘What you want to study?’, Anne-Marie asks, ‘That we’re bad? We steal? We gangbang?’

In Helen’s journey to Cabrini-Green, the film seems initially to reference the ‘yuppie in peril’ movies of the 1980s and 1990s – including films such as Into the Night (John Landis, 1985), After Hours (Martin Scorsese, 1985) and Judgment Night (Stephen Hopkins, 1993) – in which white, middle-class characters find themselves ‘lost’ in an urban environment whose ethnic diversity is equalled by its sense of danger. However, as Candyman progresses and the story of the Candyman is revealed to the audience, the Candyman himself becomes increasingly sympathetic – more than a simple ‘bogeyman’, the Candyman is a rounded character, his violent demise currying audience sympathy despite his abduction of the baby. As his interactions with Helen deepen, the Candyman makes her a passive witness to his brutal crimes. In Helen’s journey to Cabrini-Green, the film seems initially to reference the ‘yuppie in peril’ movies of the 1980s and 1990s – including films such as Into the Night (John Landis, 1985), After Hours (Martin Scorsese, 1985) and Judgment Night (Stephen Hopkins, 1993) – in which white, middle-class characters find themselves ‘lost’ in an urban environment whose ethnic diversity is equalled by its sense of danger. However, as Candyman progresses and the story of the Candyman is revealed to the audience, the Candyman himself becomes increasingly sympathetic – more than a simple ‘bogeyman’, the Candyman is a rounded character, his violent demise currying audience sympathy despite his abduction of the baby. As his interactions with Helen deepen, the Candyman makes her a passive witness to his brutal crimes.

Aside from transposing the story from Liverpool to Chicago and deepening the mythos of the Candyman – replacing the emphasis on class divisions implicit throughout Barker’s narrative with a theme of racial disharmony more relevant to the immediate setting of the picture – Rose’s film is remarkably faithful to Clive Barker’s short story, to the extent that a number of the more memorable lines of dialogue are lifted straight from the page (‘What’s blood for, if not for shedding?’), as is some of the imagery (the huge graffiti depiction of the Candyman in which his mouth functions as a door). Concerning Rose’s decision to build into the narrative the racially-motivated persecution and murder of the Candyman, and the relationships between ethnicity and poverty/deprivation indexed by the Cabrini-Green setting, Linda Badley notes that in Candyman ‘[t]he real horror was not Candyman’s splitting victims from end to end but the specters of racism, black on black violence, the hopelessness and fatalism of the hood, the myth in which black men fatally desire white women and vice versa […] and the perverse power of legend or myth itself’ (Badley, 1996: 142). As a result of this, the Candyman becomes, in the words of Paul Wells, ‘an ideologically charged “monster”, clearly playing out narratives of racial vengeance and redemption in modern America’ (Wells, 2002: 173). As Helen’s husband Trevor asserts during his lecture, urban myths are ‘bedtime stories. These stories are modern oral folklore. They are the unselfconscious reflection of the fears of urban society’. The Candyman’s presence ‘reminds contemporary culture of its collective sins, most particularly in regard to the treatment of non-white communities and civil liberties’ (ibid.). The Candyman lives through the oral folk tales that are told about him. When Helen’s investigation leads to the capture of Ruthie Jean’s killer, it seems that the legend of the Candyman has been disproven; the Candyman resurfaces with a vengeance, in order to validate his existence and reignite belief in him. (‘Believe in me. Be my victim’, the Candyman demands of Helen, ‘Your disbelief in me destroyed the faith of my congregation. Without them, I am nothing. So I was obliged to come, and now I must kill you. Your death will be a tale to frighten children, to make loves cling closer in their rapture’.) As Kirsten Moana Thompson has argued, ‘Candyman suggests that oral storytelling and, by extension, urban legends are valuable forms of historical memory, and that the price of historical amnesia will be apocalyptic (“I came for you”)’ (Thompson, 2012: 59).

Video

Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Candyman contains two presentations of the film, housed on separate disc. Both presentations fill just under 27Gb of space on their respective dual-layered Blu-ray discs. Arrow’s new Blu-ray release of Candyman contains two presentations of the film, housed on separate disc. Both presentations fill just under 27Gb of space on their respective dual-layered Blu-ray discs.

As fans will know, Candyman exists in two different versions. Both edits of the film have the same runtime (99:17 mins). The edit of the film contained on previous DVD releases has been the US ‘R’ rated cut, whereas the version of the picture released to cinemas in the UK (and on LaserDisc and VHS over here too) featured some alternate – more graphic – footage in the scene in which the Candyman butchers the psychiatrist who is assessing Helen. (In the version of this scene that made its way onto UK cinema screens, more blood splatter is seen and the Candyman is shown ripping his hook through the body of his victim.) Disc Two contains the US ‘R’ rated cut of the film, and Disc One of Arrow’s Blu-ray release contains the unrated version of the film, with the more graphic death of the psychiatrist, labelled as the ‘UK theatrical version’. The more violent footage excised from the US ‘R’ rated cut is composited into the main presentation from a lower quality source. (There is a noticeable ‘jump’ in video quality, with the inserted material having a much coarser structure and bolder contrast – suggesting it is from a positive source, perhaps a 35mm print.)  Aside from the footage inserted into the version of the film that is contained on Disc One, Arrow’s presentation of Candyman (shot on colour 35mm stock) is based on a new 2k restoration sourced from a 4k scan of the negative and looks absolutely spectacular. The film is lovingly shot and lit, with some Classical Hollywood-style use of diffused light in the close-ups of Virginia Madsen, including a very ‘retro’ use of an eye light in some scenes. This subtle lighting is complemented in this presentation by very nicely balanced contrast levels, which offer strong midtones and subtle gradation into both the shoulder and the toe. The autumnal palette of the main feature (with plenty of browns and muted greens) is communicated excellently; colours are naturalistic and skintones seem accurate. The level of detail within the main feature is extremely pleasing, plenty of fine detail being present in close-up shots. Finally, the presentation is organic and film-like, the structure of 35mm film being retained through an impressive encode to disc for both presentations of the main feature. Aside from the footage inserted into the version of the film that is contained on Disc One, Arrow’s presentation of Candyman (shot on colour 35mm stock) is based on a new 2k restoration sourced from a 4k scan of the negative and looks absolutely spectacular. The film is lovingly shot and lit, with some Classical Hollywood-style use of diffused light in the close-ups of Virginia Madsen, including a very ‘retro’ use of an eye light in some scenes. This subtle lighting is complemented in this presentation by very nicely balanced contrast levels, which offer strong midtones and subtle gradation into both the shoulder and the toe. The autumnal palette of the main feature (with plenty of browns and muted greens) is communicated excellently; colours are naturalistic and skintones seem accurate. The level of detail within the main feature is extremely pleasing, plenty of fine detail being present in close-up shots. Finally, the presentation is organic and film-like, the structure of 35mm film being retained through an impressive encode to disc for both presentations of the main feature.

For some full-sized screengrabs, including grabs from the material exclusive to the ‘UK theatrical version’, please see the images at the bottom of this review and click to enlarge them.

Audio

On Disc One, the film is presented with a LPCM 2.0 stereo track and optional English subtitles for the Hard of Hearing. The US ‘R’ rated cut on Disc Two contains the same LPCM 2.0 stereo track alongside a more modern DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track and optional English HoH subtitles. The stereo track is fine, with depth and clarity, showcasing Philip Glass’ funereal score. The 5.1 track adds some extra sound separation but the stereo track is perfectly serviceable and will be the purist’s choice. The subtitles are easy to read and accurate in transcribing the film’s dialogue.

Extras

DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

*The Film (UK theatrical version) (99:17) - ‘The Cinema of Clive Barker: The Divine Explicit’ (28:09). In a new interview, Barker talks about his work’s relationship with cinema, discussing his initial apathy towards filmmaking which evolved with the making of Hellraiser in 1987. He reflects on the ongoing popularity of Hellraiser and its sequels, and he discusses the issues surrounding the production (and post-production) of Nightbreed in 1990. He talks about the appeal of monsters and some of the recurring themes in his work (for example, the sado-masochistic subtext of Hellraiser). DISC TWO: *The Film (US ‘R’ rated version) (99:17) - Audio commentary with Bernard Rose and Tony Todd. This is an excellent, insightful commentary, Todd and Rose offering vivid recollections of the making of the picture. They consider some of the contextual factors in the film’s production and discuss some of its themes, talking about how Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’ was adapted to the US setting of the film. - Audio commentary with critics Kim Newman and Stephen Jones. Newman and Jones reflect on the work of Clive Barker and their personal connection with the publication of the Books of Blood. They talk about ‘The Forbidden’ and its publication history. Newman and Jones reflect on the other film adaptations of the stories in the Books of Blood. They discuss Bernard Rose’s approach to adapting ‘The Forbidden’ and talk about the impact of the US setting on the narrative. - ‘Be My Victim’ (9:46). Tony Todd is interviewed about Candyman. He talks about how he was approached to play the role, against the wishes of production company Propaganda, who wanted ‘an Eddie Murphy type’. Todd aimed towards the ‘Gothic elegance’ of Lon Chaney’s performance in The Phantom of the Opera (1925). Todd also gives some excellent insight into his approach to acting, and he reflects on how Rose helped to draw out the relationship between the Candyman and Helen through rehearsals with Todd and Virginia Madsen. He talks about the location shooting, noting that some of the young men in the Cabrini-Green scenes are real gang members, and he discusses the controversies surrounding the film’s depiction of racial divisions.

- ‘It Was Always You, Helen’ (13:10). Virginia Madsen talks about how she came to be cast in the film, after Bernard Rose’s wife – who was originally to play Helen – fell pregnant. Madsen discusses her approach to playing Helen, which involved eating ‘a lot of pizza’ because ‘Bernard wanted me to be a little bit more “round”’. Madsen reflects on the character of Helen and what she found interesting about the part. She also talks about Bernard Rose’s approach to directing. - ‘The Writing on the Wall’ (6:21). The film’s production designer, Jane Ann Stewart, reflects on the film’s production design. She highlights the importance of ensuring that Helen’s apartment was depicted as being built in ‘exactly the same way’ as the apartments in Cabrini-Green. She also talks extensively about the design for the lair of the Candyman. - ‘Forbidden Flesh’ (8:01). The film’s makeup effects artists – Bob Keen, Garry Tunnicliffe and Mark Coulier – are interviewed separately about their work on Candyman, talking about the film’s makeup and other effects (including the Candyman’s hook). - ‘A Story to Tell: Clive Barker’s “The Forbidden”’ (18:38). Author Douglas E Winter talks about Clive Barker’s short story ‘The Forbidden’, contextualising this within the popularity of literate horror fiction during the 1980s and 1990s. Winter talks about his introduction to Clive Barker’s work, via the Books of Blood, to which Winter was introduced by Ramsey Campbell. Winter reflects on the unique nature of Barker’s work and how transgressive Barker’s fiction was (and remains). Fundamentally, Winter argues, ‘The Forbidden’ is ‘a horror story about the allure of horror stories’.

- ‘Urban Legend: Unwrapping Candyman’ (20:40). Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes, writers and enthusiasts of Candyman, talk about their relationship with the film and discuss the film’s depiction of race and racial conflict. It’s an excellent and thought-provoking little piece in which Due and Barnes engage in a lively dialogue about Candyman. - Trailer (2:04). - Gallery (0:39). - Bernard Rose Short Films: o ‘A Bomb With No Name On It’ (1975) (3:40). With shades of Conrad’s The Secret Agent, this short film depicts a man planting a bomb in a busy café. o ‘The Wreckers’ (1976) (5:58). A young man plans a party in his parents’ house, leading to nightmarish scenes of carnage and destruction. ‘Looking at Alice’ (1977) (27:24). This black and white short has a greater sense of narrative than the two other short films included on this disc, and focuses on a young man with a voyeuristic fascination in his female neighbour.

Overall

A visually powerful film supported by a superb score from Philip Glass and anchored by excellent performances from both Todd and Madsen, Bernard Rose’s Candyman offers a fascinating interpretation of Clive Barker’s source story, adapting the text from Liverpool to Chicago and, in the process, substituting a theme of racial conflict for Barker’s story’s emphasis on class difference and social mobility. As Eric Lott says, Candyman ‘has the courage as well as the intelligence to pose indelicate questions about specters of race’ (Lott, 2017). The film has had faced some criticism, acknowledged in the interview with Tony Todd on this disc and in the dialogue between Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes, for its handling of issues of race and racial divisions. Nevertheless, it’s an impactful film, with Todd’s rounded performance as the Candyman giving the picture a sense of depth – and though Todd would continue his role in the film’s two sequels, neither Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (Bill Condon, 1995) nor Candyman: Day of the Dead (Turi Meyer, 1999) could recapture the potency of Rose’s original film. A visually powerful film supported by a superb score from Philip Glass and anchored by excellent performances from both Todd and Madsen, Bernard Rose’s Candyman offers a fascinating interpretation of Clive Barker’s source story, adapting the text from Liverpool to Chicago and, in the process, substituting a theme of racial conflict for Barker’s story’s emphasis on class difference and social mobility. As Eric Lott says, Candyman ‘has the courage as well as the intelligence to pose indelicate questions about specters of race’ (Lott, 2017). The film has had faced some criticism, acknowledged in the interview with Tony Todd on this disc and in the dialogue between Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes, for its handling of issues of race and racial divisions. Nevertheless, it’s an impactful film, with Todd’s rounded performance as the Candyman giving the picture a sense of depth – and though Todd would continue his role in the film’s two sequels, neither Candyman: Farewell to the Flesh (Bill Condon, 1995) nor Candyman: Day of the Dead (Turi Meyer, 1999) could recapture the potency of Rose’s original film.

Arrow’s new Blu-ray presentation contains a superb presentation of the main feature, and thankfully offers viewers the opportunity to watch the ‘unrated’ cut of the film – rather than the ‘R’ rated version that has previously appeared on digital home video formats. The new restoration is excellent and is captured very well on this new Blu-ray release, and the film itself is supported by some excellent contextual material. For fans of horror films, this is an essential purchase. References: Badley, Linda, 1996: Writing Horror and the Body: The Fiction of Stephen King, Clive Barker, and Anne Rice. London: Greenwood Press Lott, Eric, 2017: Black Mirror: The Cultural Contradictions of American Racism. Harvard University Press Thompson, Kirsten Moana, 2012: Apocalyptic Dread: American Film at the Turn of the Millennium. State University of New York Press Wells, Paul, 2002: ‘On the side of the demons: Clive Barker’s pleasures and pains. Interviews with Clive Barker and Doug Bradley’. In: Chibnall, Steve & Petley, Julian (eds), 2002: British Horror Cinema. London: Routledge Please click to enlarge:

(Grabs from the material exclusive to the ‘UK theatrical cut’)

|

|||||

|