|

|

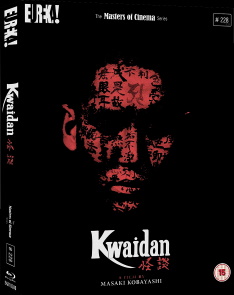

Kwaidan: Limited Edition

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Eureka Review written by and copyright: Eric Cotenas (25th March 2020). |

|

The Film

Oscar (Best Foreign Language Film): Kwaidan (nominated) - Academy Awards, 1966 Jury Special Prize: Masaki Kobayashi (won) and Palme d'Or: Masaki Kobayashi (nominated) - Cannes Film Festival, 1965 From Japan comes a floridly-colored Tohoscope and Fujicolor portmanteau of ghost stories drawn not from Japanese folklore but from Greek/Irish Lafcadio Hearn, an American correspondent living in Japan at the end of the nineteenth century whose published story collections were part of the early twentieth century oriental vogue in America and England. That the film had until the more recent international J-Horror craze following the releases of Ringu and Ju-on: The Grudge been one of the best-known and widely-seen examples of Japanese horror – alongside Onibaba – was due to the approach of the increasingly internationally-concerned director Masaki Kobayashi (The Human Condition) to present an occidental view of Japan in the film. The title of the first story alone "Black Hair" – actually found in the Hearn collection "Shadowings" – plucks one of the most iconic aspects of classical and modern Asian horror while the story itself sets up a running theme through the film: supernatural retribution for the breaking of oaths and vows. In feudal Japan, a samurai (Vengeance is Mine's Rentarô Mikuni) reduced to poverty by the ruin of his lord, walks out on his devoted first wife (Sword of Doom's Michiyo Aratama) when he finds a post in a distance province. He marries the governor's daughter ('s ) and lives in luxury and comfort. As he discovers that his new wife is cold and selfish, he is plagued by guilt for abandoning his first wife and longs for a reconciliation. He returns to find much of their home in largely in ruins, but a light through the window of the main room reveals his first wife seemingly just as he left her… or is she? Based on the Hearn story "The Reconciliation," "Black Hair" introduces ambiguity into the scenario as to whether the protagonist is actually feels remorse or just the desire for a completely devoted spouse. Flashbacks to his dutiful first wife at her spinning wheel and loom awaiting his joyous return meld with his imaginings of the reunion in which there is no sense of reproach. When he returns, his first wife does indeed say as if reading his mind: "Don't reproach yourself. It's wrong to allow yourself to suffer on my account. I always felt that I wasn't worthy of being your wife." Whereas the story lets the husband off with a scare before the final revelation, the film version takes things to frightening lengths before one final sting. Seasick combinations of camera tilts and dolly moves along with a dissonant merger of sound and score by composer Tôru Takemitsu who interjected into John Williams' more lyrical score for Robert Altman's Images treated sounds and voices to suggest something off about the fantasy world of its mentally-ill children's author protagonist. In the second story "The Woman of the Snow" – which actually comes from the Hearn collection titled "Kwaidan" – a village woodsman and his eighteen-year-old apprentice Minokichi ('s ) are caught in a fierce blizzard and seek shelter in the ferryman's hut when they cannot cross the river home. A chilled Minokichi administers to his older mentor before falling asleep, only to wake to the site of a beautiful woman who drains the older man's warmth with her icy breath. She turns to Minokichi but hesitates, telling him that she has taken pity on him but will not hesitate to kill him should he ever tell anyone about what he has seen. After a lengthy convalescence under the care of his mother ('s ), Minokichi goes back to work and crosses paths with an orphaned young woman Yuki ('s ) on her way to Edo to look for work. He offers her the hospitality of his mother's home for the night, but she ends up staying and marrying him, giving him three children. The years pass and his devotion to her never wavers, but he feels guilty for holding back one secret from her, particularly as she sometimes reminds him of the woman of the snow. Dare he tell his wife the one thing he has been keeping from her, and what will be the repercussions? The surprise reveal should be no surprise to the seasoned horror viewer – or those who know that the story was titled "Yuki-onna" with Hearn providing the meaning for the name Yuki in a footnote on the page on which she is introduced – but both story and film have a different, possibly more devastating, punishment in mind for the young protagonist's transgression. The most surrealistic of the episodes, "The Woman of the Snow"'s setting is a woodland of symmetrical tree trunks and fields of tall grass set before a large cyclorama in which the sun and moon take on the increasingly recognizable semblance of peering eyes while theatrical lighting changes from red-orange dusk to warm interiors to icy blue show just how easy it is to transform a visage from beauty to terror. This episode, and/or Hearn's source story, has one of the film's two more traceable Japanese myths; having antecedents in Japanese cinema going back to the silent days, while the Kwaidan segment inspired a 1968 feature adaptation from competing production company Daiei, and more recently a 2016 film (both of which cite the Hearn story as their source) while the "Lover's Vow" segment of Tales from the Darkside: The Movie does not credit Hearn even though Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Stephen King are cited for the other two stories. In the most-celebrated tale, "Hoichi the Earless" (the source of which for Hearn dates back to a 1782 story collection by Isseki Sanjin) is a blind monk at the Amidaji temple who has attained some local notoriety as a biwa player who can recite all one hundred parts of "The Tale of the Heike" about the war between the Genji and Heiki clans, the latter finally being defeated in the Battle of Dan-no-ura that took place on the sea near the temple seven hundred years prior, during which the infant empress and the rest of the female retinue jumped off the boat into the sea rather than be captured. One night, Hoichi (Kagerô-za's Katsuo Nakamura) receives an order from a samurai (You Only Live Twice's Tetsurô Tanba) who is tasked with bringing him to the house of his lord for a private performance. Unbeknownst to Hoichi, his audience is composed of ghosts and their palace is the old cemetery which comes to life at night to hear him recite the Battle of Dan-no-ura. After a few mornings in which Hoichi returns exhausted and unable to tell the head priest (Ikiru's Takashi Shimura) of his whereabouts due to his vow, two temple attendances Yasaku (Sanjuro's Kunie Tanaka) and Matsuzo (The Face of Another's Eiko Muramatsu) follow him and discover him performing in the graveyard to the crumbled monuments. The head priest tells Hoichi that he has been performing for ghosts, and that they will tear him to pieces now should he go with them again. The head priest and his attendant paint the characters of the Heart Sutra over Hoichi's entire body, rendering him invisible to ghosts; however, they neglect to paint his ears… hence the title. The longest and grandest of the stories, what with its tale within a tale performed on a soundstage sea and the contrast of naturalistic environs with the similarly stagey graveyard turned ghostly palace, "Hoichi the Earless" has more than a bit of comic relief and the film's most startling brutality, however, but turns the story's happy ending into something a bit more poignant with the protagonist's resolve "I'll play the biwa as long as I live to console those sorrowful spirits." The final story is also a tale within a tale, or a tale "In a Cup of Tea", in which an author (The Loyal 47 Ronin's Osamu Takizawa) in eighteenth century Kyoto muses on the reasons that a story may be left unfinished, using as an example a story from centuries earlier in which Kannai (The 47 Ronin's Kan'emon Nakamura), an attendant of Lord Nakagawa whose court has stopped in Hakusan for the New Year's celebration, pours himself a cup of tea at a temple and is perplexed to discover the reflection of another man staring back at him from within the cup. As he looks again, dumps the tea, and checks again, the other man's expression becomes more mocking and challenging. Unable to explain the event, he drinks the tea only to receive a visitation that night by the man Shikibu Heinai (Lady Snowblood's Noboru Nakaya) who at first seems amiable but grows increasingly sinister; whereupon Kannai attacks him with his sword only for the man to vanish into the shadows. He rouses the entire house but there is no trace of the stranger, and he becomes a laughing stock of the rest of the retinue. Later that night, however, three men appear to Kannai claiming to be retainers of Heinai who they claim will visit him again on the sixteenth day of the next month to repay the injury dealt to him. The tale ends there, with the author leaving it up to the reader to muse on the possible outcomes; however, when the author himself cannot be found, his housekeeper (Tokyo Story's Haruko Sugimura) and publisher (Floating Weeds' Ganjirô Nakamura) discover one horrifying possibility. While the final story cannot help but seem like the anthology's weak link, but even the author attempting to relate the unfinished tale of another might be seen as a transgression; and perhaps the final image is that is the only way an anthology without a framing story could find an ending. Although the horror anthology was not exactly a new trend – one of the trendsetters being Ealing Studios' Dead of Night – the format had sort of a rebirth with Kwaidan finding contemporaries in Amicus' Dr. Terror's House of Horrors and Torture Garden (and a few more to come in the next decade), Mario Bava's Black Sabbath, as well as the Polish The Saragossa Manuscript with its tales within tales within tales. The international title for the film Kwaidan comes from Hearn's transliteration of the title for his story collection, but the more accepted transliteration as seen on the English titles of several other Japanese horror films is Kaidan, also the title of Hideo Nakata's more recent re-telling of the Meiji-era legend of Kasane Marsh.

Video

Released in Japan in a roadshow version running just over three hours, Kwaidan was shortened by roughly twenty minutes for its international release starting with the Cannes Film Festival premiere. When the film was picked up for distribution in the United States by Continental Distributing in 1965, it was further shortened to 125 minutes by omitting the "Woman of the Snow" story which was then distributed as a short subject (the American cut was also distributed in the UK in 1967 by Orb Films). When Janus Films acquired the U.S. rights, they restored the "Woman of the Snow" story, bringing the running time back up to 161 minutes, and this was the cut that Criterion brought to laserdisc in 1990 and letterboxed VHS through Home Vision Cinema – as well as Toho's 1996 laserdisc and Tartan's 1994 UK VHS – followed by the 2000 DVD. The roadshow version popped up on DVD in a slightly overmatted transfer in Japan from Toho followed by the first English-friendly edition on DVD from Eureka in the U.K. in 2006. Criterion debuted a new 2K restoration on Blu-ray in 2015, and it is this master that has also been utilized by Eureka for their 1080p24 MPEG-4 AVC 2.35:1 widescreen Blu-ray. The visually ravishing film has always looked "good" on video and DVD, but the high definition master reveals just how lacking the older transfers actually were, with an enhanced sense of depth as the camera dollies and cranes through the the studio-bound settings, a palpable disorientation as the camera tilts off its axis, and a greater appreciation of the effects of lighting changes and make-up on visages human and supernatural (particularly with regard to the fate of the samurai in the first story and the subtle changes need to turn a bride into a woman of the snow).

Audio

The film's sound design has always impressed on home video as well, but the uncompressed LPCM 1.0 track is particularly startling in its drops into complete silence splintered by sometimes deliberately mismatched or mis-synched sound effects or the low, buzzing mixing of Takemitsu's sound scoring. Optional English subtitles are provided.

Extras

Whereas Criterion's Blu-ray had a new commentary by academic Stephen Prince, an archival interview with Kobayashi, an interview with assistant director Kiyoshi Ogasawara, and a discussion of Hearn's works by academic Christopher Benfey, Eureka's Blu-ray features “Shadowings” (35:45), a video essay by film historians David Cairns & Fiona Watson who discuss Kobayashi taking the project up in the wake of the international success of Harakiri/Seppuku , some background on Hearn and his Japanese wife who helped him collect the tales – paralleled with Kobayashi's partnership with the film's female screenwriter Yôko Mizuki (Floating Clouds) – as well as production anecdote from the need to use an airplane hangar to fit the immense sets, the amount of electricity and lighting required, and going over-budget bankrupting the production company and requiring Kobayashi to sell his home to finish the film, followed by some assessments of the adaptations and their sources, and the important contribution of composer/sound designer Takemitsu. Also new is “Kim Newman on Kwaidan” (24:24) in which he notes how well-known the film is internationally compared to prior Japanese ghost movies, contrasting the noir-ish approach to some of the other films compared to Kobayashi's color stylization, and the film's influence on subsequent Japanese horror films. Carried over from the Criterion discs are a trio of trailers: a B+W Japanese Theatrical Trailer (1:04), a Colour Japanese Theatrical Trailer #1 (1:25), and a Colour Japanese Theatrical Trailer #2 (3:58).

Packaging

Housed in the case is a limited edition 100-page perfect bound illustrated collector’s book featuring reprints of Hearn's four stories, a translation of the Heart Sutra, a reprint of the final interview with Kobayashi by Linda Hoaglund with Peter Grilli, a note on the transliteration of the title by Nick Des Barres, and the essay "A Haunted Nation" by Craig Ian Mann placing the film in the context of other horror anthologies and musing on the critic arguments over the years as to whether Kwaidan is a horror film or art film.

Overall

A Japanese horror portmanteau by a Japanese filmmaker from Japanese tales as related by a non-Japanese author, Kwaidan's attempt to present an "occidental version of Japan" is just one of the reasons the film is a celebrated work of the genre.

|

|||||

|