|

|

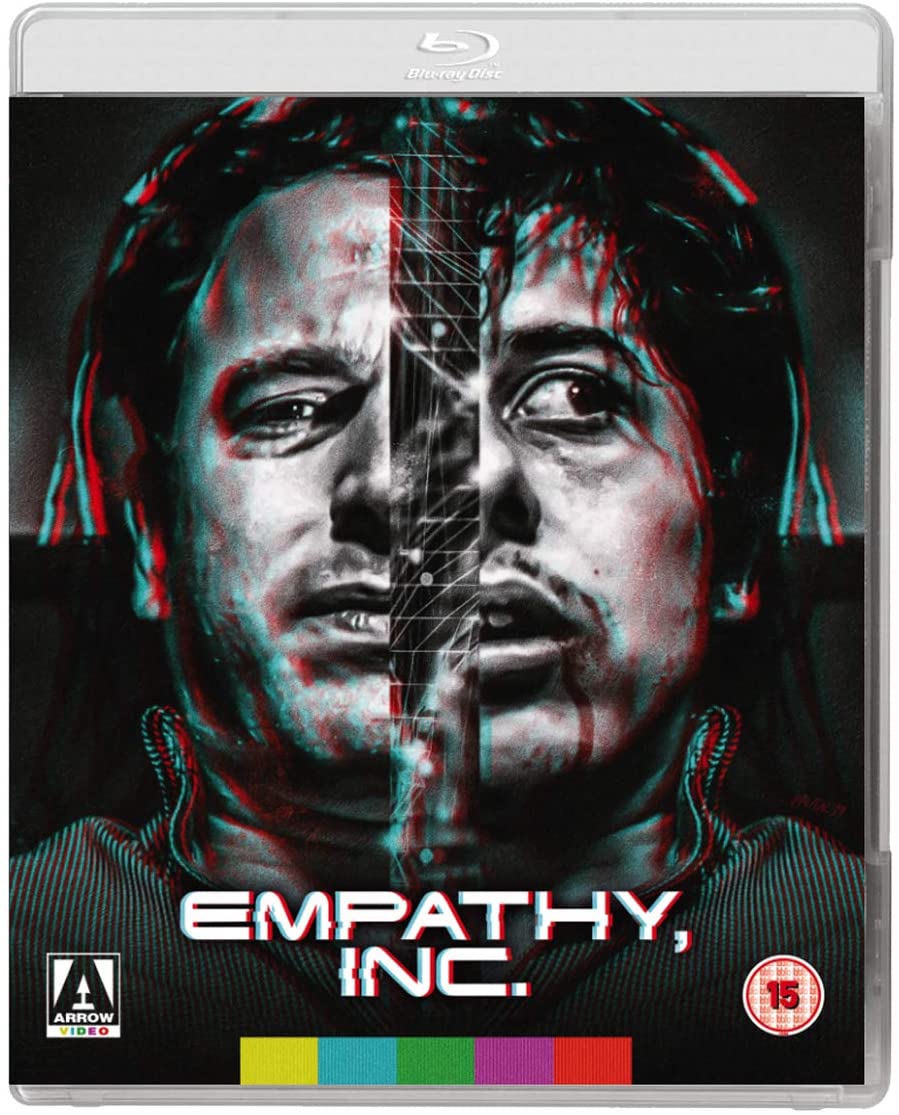

Empathy, Inc (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (30th May 2020). |

|

The Film

Empathy, Inc. (Yedidya Gorsetman, 2018) Synopsis: When start-up tech firm GTI (Genesis Technology Integrated) goes bankrupt, investor Joel (Zach Robidas) finds himself a pariah in the business world. Losing his house, he is forced to move in with his wife Jessica’s (Kathy Searle) parents. Ward (Fenton Lawless), Jessica’s father, reveals to Joel that he has a million dollars in savings. Soon afterwards, Joel encounters an old schoolmate, Nicky ‘Sleazy’ Beezy (Eric Berryman), who tells Joel of an investment opportunity focused on a unique ‘virtual experience’ – X-VR, developed by Nicky’s business partner Lester (Jay Klaitz) – which allows clients to place themselves in the shoes of someone less fortunate. Nicky asks Joel if he would like to be involved in the business, using his prior experience to raise investors for X-VR. Joel insists on experience X-VR himself, finding himself as a balding middle-aged man with stomach problems. Exiting the machine, Joel is impressed and commits himself to the project, beginning to concoct a plan to encourage Ward to invest in Nicky’s business. However, Joel is still wary of Nicky, something which is compounded by Nicky’s distrustful attitude and a conversation Joel has with a former colleague at GTI, Sonny (A J Cedeno). One night, Joel sneaks into Nicky and Lester’s dingy offices and jacks into the X-VR machine. He comes to as a young man, who steals something from a shop and gets into a violent altercation with a policeman. Jessica discovers that Joel has persuaded Ward to invest in X-VR and is furious. The money Ward had saved was to be used to purchase a house for Jessica and Joel. Joel also discovers that X-VR isn’t a simulation – it actually enables its users to swap bodies with another human subject. He tries to get Ward’s money back from Nicky, but Nicky informs Joel that the night he broke into the offices to experiment with the X-VR machine, Joel swapped bodies with a criminal who, whilst inhabiting Joel’s body, committed a violent murder. Critique: ‘“To thine own self be true”. At least, that’s what I used to think’, we hear the voice of Joel intone as Empathy, Inc. opens, before he continues by asking ‘Of all the different people we are inside, who are we to be true to?’ Joel is shown to be on a stage, speaking to an audience, low-key lighting picking out the faces of his listeners in the darkness. At the end of the film, after the main thrust of the narrative has concluded, we are brought back to this scene – which, taking place at an indeterminate moment in the future and strangely disanchored from the main story, bookends the picture. ‘Who am I?’, Joel asks in this final coda, ‘Who was I before? And when I leave this stage, who will I be?’ This moment foregrounds the theme of identity that bubbles beneath Empathy, Inc.’s outward focus on low-key sci-fi trappings (of the kind that might invite comparison with Shane Carruth’s Primer). In many ways, the narrative of Empathy, Inc. may be taken as a metaphor for acting – which is, after all, the practice of allowing another character to inhabit one’s body, or through mimetic action to give embodiment to a scripted character. Acting is performative, and Empathy, Inc. suggests quietly that our more general sense of self-hood is equally performative. This is of course a theme that recurs throughout science-fiction, from the monster’s search for identity in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818/36) onwards. Where does ‘identity’ reside, and if our identities are mutable, what is our relationship with others? Where traditionally, debates about identity have focused on either centralism (ie, the notion that the self is located within the brain) or embodiment, in the digital age the concept of virtual identities has become increasingly important. Empathy, Inc. attempts to engage with this development – and its relationship with traditional models of identity – by exploring the notion of a device which, though initially presented to Joel as a Virtual Reality machine (‘X-VR’, wich Nicky tells Joel stands for ‘Extreme Virtual Reality’), enables the self to ‘jump’ from one person to another. In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Atticus Finch explains the concept of empathy to his daughter Scout, the book’s young narrator, by asserting that ‘You never really understand a person until you understand things from his point of view […] until you climb into his skin and walk around in it’. This valuable life lesson echoes throughout Empathy, Inc., whose premise revolves around the retro-styled invention that Lester has invented to allow consciousness to be transferred between human subjects. When Nicky pitches this invention to Joel, he paints the invention as a VR-style device (‘it’s realer than anything anybody has ever seen’), hiding from his potential investor the fact that the machine is predicated on ‘body swapping’ – from his intended privileged clients to less privileged members of society, giving the former an opportunity to experience life on the other side of the tracks. Nicky rationalises that by experiencing apparently vicarious hardship, this will result in his clients experiencing a greater appreciation of their fortunes. ‘We allow high-end clientele to experience what it’s like to be privileged’, Nicky explains, ‘People want to be rich. What they want to feel like is different. Me and Lester remind them of what they have’ by offering ‘perspective [….] Walk a mile in the shoes of the less fortunate, and when you wake up, what problems you do have feel better’. It’s a form of poverty tourism, another way in which the comfortable middle classes can exploit the lives of the disadvantaged. In fact, this premise might remind the viewer strongly of the Pulp song ‘Common People’, and Jarvis Cocker’s bitter refrain of ‘Everybody hates a tourist / Especially one who thinks it’s all such a laugh / And the chip stains and grease / Will come out in the bath’. When Joel asks to try out X-VR for himself, Nicky takes him to a rundown office. The setting certainly doesn’t inspire confidence, and Nicky discovers the machine itself has a decidedly lo-fi appearance – a multitude of wires, some old computer parts, and a headset that is not unlike the headset Max Renn (James Woods) is told to wear in David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). Lester fills a hypodermic needle with a solution that he intends to inject into Joel. ‘What is that for?’, Joel asks. ‘What makes it work’, Lester tells him. Joel, and the audience, may wonder if he is simply being fed a hallucinogen. He is given a number of rules by Lester: ‘Number 1: the code is unstable, so stay in the environment you wake up in. Don’t go opening any doors [….] Number 2: don’t underestimate X-VR. It’ll feel like your real body, but it’s not your real body [….] Number 3: avoid mirrors at all costs. Seeing yourself in somebody else’s body can kind of fry your brain’. As Joel enters the machine, we cut to his point-of-view: the 2.35:1 frame is matted to a narrower screen ratio, with vignetting at the edges of the visible image. The effect, like having tunnel vision, recalls Jonas Akerlund’s video for The Prodigy’s ‘Smack My Bitch Up’ (or Gaspar Noe’s similar use of POV post-Irreversible); Joel finds himself in a barely-furnished flat and discovers he is now a balding middle-aged man with stomach problems. When the trip ends, Joel is astonished. ‘I feel more like myself than I have in a really long time’. Empathy, Inc. is as much about today’s world of shady tech start-ups and the perils of investing in these, as it is about its soft SF premise focusing on body/consciousness swapping. With the collapse of GTI – a company based on Joel’s partner Craig’s patenting of a way ‘to catalyse water. No pollution, just steam. We were going to save the world’ – Joel finds himself used as a scapegoat for the company’s failure, which Joel describes as ‘a $90 million screw-up’. He discovers that Craig lied about the process on which GTI was founded. ‘Word of advice, Joel: don’t believe everything you see’, Craig advises him. When, after moving in with Jessica’s parents, Joel encounters Nick, Nick offers Joel some much more nihilistic business advice: ‘You go up, you go down; but in the long run we’re all dead, so who gives a fuck?’ Along the way, Empathy, Inc. explores some interesting sidebars. As the film builds towards its climax, Joel uses the X-VR device to swap bodies with the overweight, slob-like Lester. As Lester, Nicky must contact Jessica, and he tells her that despite his appearance he is in fact Joel, her husband. He is shocked when Jessica tries to seduce him, protesting, ‘I am not me’. However, he soon realises that Lester has, disguised as Joel, abducted Jessica and swapped bodies with her – and who Joel believes is his wife is in fact Lester. ‘Do you know how good it feels to fuck yourself?’, Jessica/Lester asks a horrified Joel. Previously, Nicky warned Joel about Lester: ‘I’m a greedy motherfucker’, Nicky said, ‘but Lester is the psychopath’. Though only a fragment of a film which focuses on a much broader set of anxieties, this sequence hints at a strange, unsettling narcissism within Lester, whose motivations in designing the X-VR machine are already checkered. The ease with which the users of X-VR inhabit the bodies of those less fortunate speaks of anxieties over unemployment and economic collapse in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. At any time, it seems, we are only a step away from abject poverty. Climbing up the ladder is hard, if not impossible, but falling from its middle rungs to land in a heap at the bottom is all too easy. When Joel uses the X-VR device and finds himself as a balding middle-aged man with stomach problems, we might wonder if this is his reality. ‘You think it’s fake but it’s real’, Joel tells Jessica later in the film, and Nick reminds Joel ‘When you become someone else, they become you’. Ultimately Lester’s response to Joel’s question about why he developed the X-VR machine speaks of a motivation driven by bitterness at the impossibility of social mobility. ‘Why’d you do this?’, Joel asks ‘You know, when I was a kid they told us we could be whoever we wanted to be’, Lester responds, ‘I actually believed it’.

Video

NB. This review is based on a viewing of a streaming link that was provided to us. Therefore we cannot comment in detail on the Blu-ray presentation, audio or extras. Empathy, Inc. has a running time of 97:17. Photographed digitally, in monochrome, Empathy, Inc. makes very film noir-esque use of chiaroscuro, using low-key lighting with heavy shadows to create a sense of threat. The film is presented in its intended screen ratio of 2.40:1. The shifts in screen ratio (from the film’s dominant 2.40:1 screen ratio to a much narrower ratio), to signal the characters’ entry into X-VR, are reminiscent of the shifting aspect ratios in Douglas Trumbull’s Brainstorm (1983), which uses a wider aspect ratio than the main footage to signify the characters’ experiencing of virtual reality.

Audio

Arrow’s disc carries a LPCM 2.0 stereo track with optional English subtitles.

Extras

Extras include: - An audio commentary with director Yedidya Gorsetman and writer Mark Leidner - ‘Behind the Scenes 360 (Degrees)’ - Deleted Scenes - International Trailer - UK Trailer

Overall

Empathy, Inc. feels incredibly timely, in its exploration of tech firms with shady morals. Nicky and Lester’s business practices (developing an app that enables them to blackmail their investors; creating the X-VR system) feels very ‘on point’ in the wake of the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal. The only difference is the sense of scale: Nicky and Lester are really low-bit hoods, whereas their corollaries in the real world are much more powerful and therefore more fearsome. The ‘body swap’ premise could be taken as a metaphor for acting but also underscores the vicarious, voyeuristic pleasures involved in the film-going experience itself. Empathy, Inc. is an interesting film, an effective picture which contains a sci-fi premise but feels much more like a neo-noir movie, something which is amplified by the low-key black and white photography. The film’s minimalistic approach to the X-VR device that enables subjects to swap bodies is not dissimilar to the handling of time travel in Shane Carruth’s Primer, though there seem also to be nods to Videodrome (in terms of the design of the X-VR headset) and Douglas Trumbull’s Brainstorm – and, by extension perhaps, Kathryn Bigelow’s Strange Days (1995). It’s also very well shot, the digital black and white photography creating a strong ambience. Cleverly-plotted, well-shot and with strong performances, Empathy, Inc. is a joy to watch and offers plenty of food for thought.

|

|||||

|