|

|

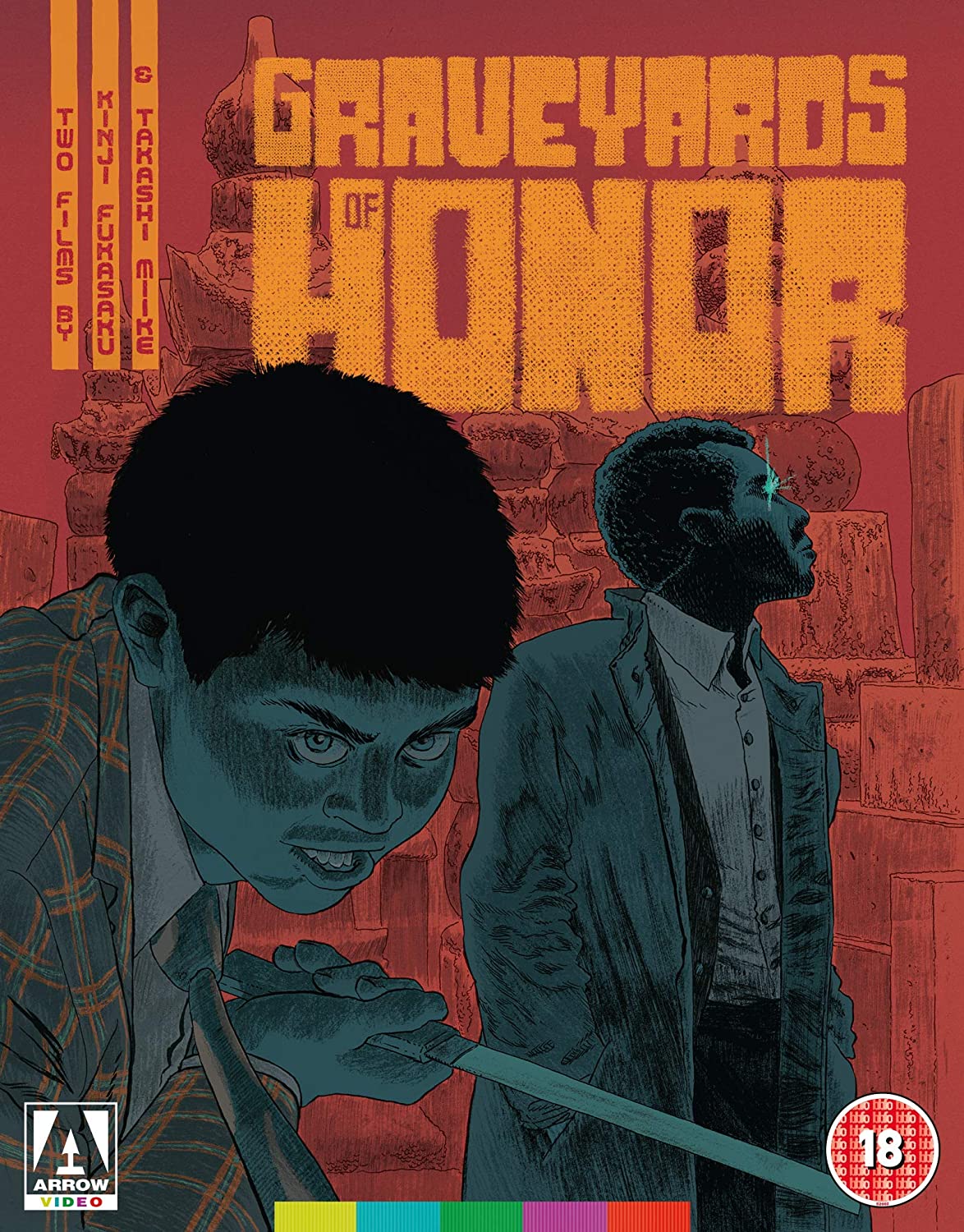

Graveyard of Honor AKA Shin jingi no hakaba (Blu-ray)

[Blu-ray]

Blu-ray B - United Kingdom - Arrow Films Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (19th November 2020). |

|

The Film

Graveyards of Honor  Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku Kinji, 1975) Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku Kinji, 1975)

Synopsis: Ishikawa Rikio (Watari Tetsuya) is a member of the Kawada family. He soon crosses paths with members of the Shinwa family. Ishikawa is warned that his actions may lead to reprisals against the Kawada family, but Ishikawa shrugs off the warnings of higher-ups within his clan – including the boss of the Kawada family. Ishikawa is enlisted by two members of the Imai family, Imai Kozaburo (Umemiya Tatsuo) – the future boss of the Imai family – and Sugiura Makoto (Go Eiji), in putting the third nationals ‘in their place’. Fleeing from the authorities after this moment of violence, Ishikawa seeks refuge in a brothel, in the room of prostitute Chieko (Takigawa Yumi), where he hides the pistol he is carrying. When the dust settles, Kozaburo suggests that Ishikawa leave the Kawada family, instead joining the Imai Clan in Tokyo. Meanwhile, Ishikawa has become besotted with Chieko and returns to her abode ostensibly to retrieve his gun, and sexually assaults her. Nozu Kisaboru (Ando Noboru), the boss of the Nozu family, is standing for election and hoping to ‘go legit’. The Nozu and Imai families are associated with one another. However, this alliance is threatened when Ishikawa sees Chieko in a nightclub and sexually assaults her again, causing a fight between Ishikawa and a member of the Ikebukuro Shinwa clan. This requires the Imai family to make a peace offering to Nemoto Noboru (Narita Mikio), an elder of the Ikebukuro Shinwa clan, thus preventing further retaliations. However, Ishikawa leads the two families into a street war, leading to the boss of the Imai family asking Nozu for some form of mediation with the Shinwa clan. Ishikawa’s self-destructive behaviour escalates. He resorts to tormenting and then assaulting members of his own gang, and even sets fire to Nozu’s car following a minor disagreement. In response for these acts, Ishikawa is ordered by Kawada to commit yubitsume, removing his finger. However, Ishikawa reacts angrily, stabbing Kawada before fleeing to the police, giving himself up. Ishikawa is given 18 months in Fuchu Prison. After being released from prison, Ishikawa spends a year in Osaka where he is treated for TB and also becomes a heroin addict, ripping off dealers. He teams up with street addict Ozaki (Tanaka Kunie).  With Ozaki, Ishikawa returns to Tokyo. He is warned by Imai to return to his exile in Osaka but refuses, and Ishikawa finds himself hunted by both the Imai and Kawada families. He is arrested again and given 10 years hard labour. Chieko, who is by now severely ill with TB herself, meets Ishikawa on his release. He is unrepentant and still addicted to junk. When Chieko dies, Ishikawa has her body cremated and takes to carrying the urn containing her ashes and bone fragments with him, chewing on the bones of his beloved. Now utterly unhinged, Ishikawa seeks revenge on Nozu and Kawada. With Ozaki, Ishikawa returns to Tokyo. He is warned by Imai to return to his exile in Osaka but refuses, and Ishikawa finds himself hunted by both the Imai and Kawada families. He is arrested again and given 10 years hard labour. Chieko, who is by now severely ill with TB herself, meets Ishikawa on his release. He is unrepentant and still addicted to junk. When Chieko dies, Ishikawa has her body cremated and takes to carrying the urn containing her ashes and bone fragments with him, chewing on the bones of his beloved. Now utterly unhinged, Ishikawa seeks revenge on Nozu and Kawada.

Critique: Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor (1975) adapts the novel by Goro Fujita, which itself was based on the real life exploits of post-war gangster Ishikawa Rikio. Graveyard of Honor remains a key film in the development of the jitsuroku – violent, often exploitative yakuza pictures of the 1970s, shot in a semi-documentary style, making use of techniques associated with newsreels and other examples of reportage. In the case of Graveyard of Honor, this includes voiceovers by various characters, reflecting on key aspects of Ishikawa’s life and character, that are presented as audio interviews; onscreen titles; overlapping dialogue; urgent handheld camerawork; abrupt editing; and the use of both black and white and sepia-toned footage (and stills, for that matter). The jitsuroku pictures had grown out of Nikkatsu’s ‘borderless action’ (mukokuseki akushon) films of the 1960s: yakuza pictures set in the present day and featuring heroes – well, actually, anti-heroes – who displayed Westernised characteristics (eg, skulking about in jazz clubs, wearing aviator shades). Prior to the film noir-esque mukokuseki akushon, the yakuza had mostly been featured in jidaigeki (period) films – where the Westernised characters were invariably antagonists. By contrast, the yakuza films of the 1960s and 1970s often featured anti-heroes with Westernised characteristics: in Graveyard of Honor, for example, Ishikawa spends much of the film skulking around in aviator shades that conceal his eyes (and therefore his emotional reactions) from the other characters. The sunglasses Ishikawa wears are a form of armour, a method of defence – even indoors or at dusk. (Using clips from this film, one could easily assemble a music video for Corey Hart’s 1984 hit ‘Sunglasses at Night’.)  With his 1972 film Street Mobster (reviewed by us here), Fukasaku produced a new kind of yakuza picture in which a noir-ish narrative sensibility and documentary style coalesced. Street Mobster was the first of Fukasaku’s films that the director ‘felt really successfully blended that documentary feel with the fictitious drama’, he told Chris Desjardins (Fukasaku, in Desjardins, 2005: 16). With Street Mobster, Fukasaku became ‘more aware of the real past and contemporary underworld, characters and events I could draw on to give the films a more reality-based feeling’ (Fukasaku, in ibid.). He based the narrative of Street Monster on the true story of Ishikawa Rikio, later using this as a more direct foundation for Graveyard of Honor. Fukasaku claimed that he was drawn to the story of Ishikawa because ‘he had come from the same area as me down in Mito […] I decided to incorporate elements of his character in Street Mobster to see how it would work. When it turned out well, I made up my mind to do the story in an even more realistic style in Graveyard of Honor’ (Fukasaku, in ibid.). Street Mobster also introduced the very urgent style of handheld photography that Fukasaku would practice in his later jitsuroku pictures, including Graveyard of Honor: ‘I believe I first came to use [handheld camerawork] on [Street Mobster]’, Fukasaku commented, ‘I myself took the camera in hand and ran into the crowds of actors and extras’ (Fukasaku, quoted in Varese, 2018: 143). With his 1972 film Street Mobster (reviewed by us here), Fukasaku produced a new kind of yakuza picture in which a noir-ish narrative sensibility and documentary style coalesced. Street Mobster was the first of Fukasaku’s films that the director ‘felt really successfully blended that documentary feel with the fictitious drama’, he told Chris Desjardins (Fukasaku, in Desjardins, 2005: 16). With Street Mobster, Fukasaku became ‘more aware of the real past and contemporary underworld, characters and events I could draw on to give the films a more reality-based feeling’ (Fukasaku, in ibid.). He based the narrative of Street Monster on the true story of Ishikawa Rikio, later using this as a more direct foundation for Graveyard of Honor. Fukasaku claimed that he was drawn to the story of Ishikawa because ‘he had come from the same area as me down in Mito […] I decided to incorporate elements of his character in Street Mobster to see how it would work. When it turned out well, I made up my mind to do the story in an even more realistic style in Graveyard of Honor’ (Fukasaku, in ibid.). Street Mobster also introduced the very urgent style of handheld photography that Fukasaku would practice in his later jitsuroku pictures, including Graveyard of Honor: ‘I believe I first came to use [handheld camerawork] on [Street Mobster]’, Fukasaku commented, ‘I myself took the camera in hand and ran into the crowds of actors and extras’ (Fukasaku, quoted in Varese, 2018: 143).

As in Street Mobster, with Graveyard of Honor Fukasaku incorporated another level of realism by casting former yakuza Ando Noboru. In Graveyard, Ando plays Nozu, the gangster who tries to achieve legitimacy by standing for election. In 1964, Ando had reinvented himself as an actor after serving six years in prison for commissioning the murder of a businessman, Yokoi Hideki, who owed a debt to Ando’s group. (Ando’s story was told in a number of films, including Sato Junya’s early jitsuroku trilogy – 1972’s Yakuza and Feuds and The Untold Story of the Ando Gang: The Killer Brother, and 1973’s The True Account of the Ando Gang: Attack – which were based on Ando’s autobiography Yakuza and Feuds and featured Ando himself in the lead role.) Ando worked in an advisory role on Miike Takashi’s Deadly Outlaw: Rekka in 2002 (a film loosely based on Ando’s experiences as a yakuza), the same year that Miike directed his version of Graveyard of Honor.  Graveyard of Honor opens with a title screen which tells us that Ishikawa ‘was born on August 6th, 1924, in the Eastern section of Mikio City, Ibaraki Prefecture’. We are shown a series of black-and-white still photographs of Ishikawa’s early life, accompanied on the audio track by interviews with those who knew him. ‘He was always crying about something’, one of the interviewees suggests in reference to the young Ishikawa, ‘He’d cry for hours on end’. The semi-documentary style that Fukasaku adopts here seems to be shaped by the approach of semi-documentary films noir, but also has parallels with the cine-inchieste (investigative cinema) of Francesco Rosi, such as Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962) – itself a picture about a real life bandit that blurred the boundaries between fact and fiction. (Other techniques Fukasaku employs include using freeze-frames, accompanied with onscreen titles, each time a new character is introduced.) Ishikawa, we are told, ran away from his home in 1941 and joined the Kawada family. ‘What turned this young man into a rabid dog?’, the off-screen interviewer of Ishikawa’s acquaintances asks, ‘Was it the chaos and confusion of the post-war years?’ Graveyard of Honor opens with a title screen which tells us that Ishikawa ‘was born on August 6th, 1924, in the Eastern section of Mikio City, Ibaraki Prefecture’. We are shown a series of black-and-white still photographs of Ishikawa’s early life, accompanied on the audio track by interviews with those who knew him. ‘He was always crying about something’, one of the interviewees suggests in reference to the young Ishikawa, ‘He’d cry for hours on end’. The semi-documentary style that Fukasaku adopts here seems to be shaped by the approach of semi-documentary films noir, but also has parallels with the cine-inchieste (investigative cinema) of Francesco Rosi, such as Rosi’s Salvatore Giuliano (1962) – itself a picture about a real life bandit that blurred the boundaries between fact and fiction. (Other techniques Fukasaku employs include using freeze-frames, accompanied with onscreen titles, each time a new character is introduced.) Ishikawa, we are told, ran away from his home in 1941 and joined the Kawada family. ‘What turned this young man into a rabid dog?’, the off-screen interviewer of Ishikawa’s acquaintances asks, ‘Was it the chaos and confusion of the post-war years?’

Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor is set firmly in the post-war world of Japan, during the American occupation. One might be reminded of Daido Moriyama’s 1971 photograph ‘Stray Dog’, a high contrast black and white photograph of an unkempt street mongrel which Moriyama took in Misawa, where there was a large US Air Force base. The dog looks back at the camera, its mouth agape. Is it panting or snarling? Its eyes are muddy and its expression difficult to decode. The dog looks as if it has equal potential to collapse as it does to attack. This iconic example of Japanese street photography is often said to function as a metonym for post-war Japanese society. Certainly, there are thematic parallels between Moriyama’s photograph and a number of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku films – particularly Graveyard of Honor, with its ‘rabid dog’ protagonist who, in the void of the US occupation of the country, seems destined to either be consumed by the world of the yakuza or to tear it apart with his teeth. Certainly, in Graveyard of Honor the occupying US forces are shown to be complicit with the yakuza. Early in the film, a group of American GIs are depicted as assisting Yamada, the boss of the Kawada family, by selling crates of Johnnie Walker Black Label to the locals. The plot also confronts the fallout from the Second World War by exploring the tensions between the Japanese population and the ‘third nationals’ – Chinese, Korean and Taiwanese immigrants living in Japan. The ‘third nationals’, so named because they were a third group of occupants of Japan following the Japanese themselves and the occupying forces, were distrusted because they were treated favourably by the occupation forces, leading to a number of well-documented street battles between Japanese gangs and their ‘third national’ rivals. Some of this context is explained by the film’s voiceover, which tells the viewer that the ‘third nationals’, having been liberated by the Allied forces, therefore expressed their ‘hatred for Japanese oppression during the war’ through ‘violence against the Japanese’. The occupation and its cultural fallout is a near-constant background to the film’s plot.  Along the way, there are the retrograde attitudes towards women that we see displayed by the yakuza in many examples of the jitsuroku. ‘Send us off with a nice fuck’, Tamaru Takuji says to a prostitute before the gang head into battle, ‘Isn’t that what women are for?’ Ishikawa demonstrates his desire for Chieko by sexually assaulting her; he doesn’t seem to be aware that this is wrong, using sexual violence as a form of foreplay. Nevertheless, in the film’s later sequences Chieko forms a relationship with Ishikawa; despite his deeply unpleasant behaviour, she remains devoted to him, waiting for him always. When Ishikawa is given 18 months in Fuchu Prison, Chieko waits for him; Ishikawa returns to her and subjects her to rough sex – which seems to be his twisted way of expressing love and affection. When Ishikawa becomes a junkie during his year in Osaka, Chieko continues to wait for his return; and after he is given 10 years in prison, she meets him on his day of release. When Chieko, severely ill with TB, dies, Ishikawa has her body cremated; he picks her bones out of her ashes and places them in the urn. He wears his omnipresent sunglasses, but though we cannot see his eyes, a single tear that drips down from round the frames of his sunglasses acts as an index of his grief. This is one of the very few moments in the film during which we see Ishikawa expressing an emotion other than rage. Along the way, there are the retrograde attitudes towards women that we see displayed by the yakuza in many examples of the jitsuroku. ‘Send us off with a nice fuck’, Tamaru Takuji says to a prostitute before the gang head into battle, ‘Isn’t that what women are for?’ Ishikawa demonstrates his desire for Chieko by sexually assaulting her; he doesn’t seem to be aware that this is wrong, using sexual violence as a form of foreplay. Nevertheless, in the film’s later sequences Chieko forms a relationship with Ishikawa; despite his deeply unpleasant behaviour, she remains devoted to him, waiting for him always. When Ishikawa is given 18 months in Fuchu Prison, Chieko waits for him; Ishikawa returns to her and subjects her to rough sex – which seems to be his twisted way of expressing love and affection. When Ishikawa becomes a junkie during his year in Osaka, Chieko continues to wait for his return; and after he is given 10 years in prison, she meets him on his day of release. When Chieko, severely ill with TB, dies, Ishikawa has her body cremated; he picks her bones out of her ashes and places them in the urn. He wears his omnipresent sunglasses, but though we cannot see his eyes, a single tear that drips down from round the frames of his sunglasses acts as an index of his grief. This is one of the very few moments in the film during which we see Ishikawa expressing an emotion other than rage.

Driven by his wants and needs, Ishikawa is unhesitant in his pursuit of his desires. His relentless attempts to ‘seduce’ (read: rape) Chieko lead to a conflict between the Imai family and the Ikebukuro Shinwa clan. Given a dressing down by the boss of the Imai family, Ishikawa is unrepentant, trying to bluff his way out of trouble by stating, unconvincingly, that he started the fight deliberately in order to teach the Ikebukuro Shinwa clan a ‘lesson’. The boss of the Imai family tells Ishikawa, ‘Do you have any idea how much a gang war costs? You can’t even calculate the consequences’. Nevertheless, Ishikawa leads the two families into a street war. When approached to mediate the conflict between the Shinwa and Imai/Kawada families, Nozu suggests they approach the Americans for help, reasoning that ‘Even the Shinwa clan has to obey American orders’. After the Americans disperse the Shinwa clan following a street battle, Ishikawa is told that he has cost the Imai family a million Yen in payoffs and bribes. Yet he is still unrepentant, bragging that ‘You can thank me for kicking them [the Shinwa clan] out of our territory’. Ishikawa’s behaviour escalates with his torching of Nozu’s car and stabbing of Kawada. To escape from retaliation, Ishikawa gives himself up to the police, and is sentenced to 18 months in prison. The narrator tells us that ‘according to the yakuza code, attacking one’s godfather is an unforgivable offence. He [Ishikawa] had pitted himself against the entire yakuza world […] Any yakuza would gain in stature by killing him. Every man in the yakuza world was competing to end his life’.  Graveyard of Honor (Miike Takashi, 2002) Graveyard of Honor (Miike Takashi, 2002)

Synopsis: Lowly dishwasher Ishimatsu Rikuo (Kishitani Goro) is taken under the wing of yakuza elder Boss Sawada (Yamashiro Shinobu) after saving the old man’s life when rival gangsters attempt an assassination in the restaurant in which Ishimatsu works. Ishimatsu is made a member of the clan and promoted to a high ranking position; this results in tensions within the Sawada family. At a karaoke bar, Ishimatsu forces himself on a girl, Chieko (Arimori Narimi); but, as the kids say, he ‘catches the “feels”’ and pursues her relentlessly, demanding she look after his money when, upon killing a rival gangster in a very public setting, it looks certain that he will be sent to prison. Ishimatsu spends five years in prison. There, he makes an ally, Imamura (Miki Ryosuke), a high-ranking yakuza in the Giyu family. Upon his release from prison, Ishimatsu discovers his young associate, Masato (Ohsawa Mikio), has been promoted. The ‘bubble’ economy has tanked, and times are hard for both the mainstream population and the yakuza. Ishimatsu comes into conflict with other members of the Sawada clan, which leads to a confrontation with Boss Sawada himself – during which Ishimatsu shoots his godfather, the man who initiated him into the world of the yakuza. As Ishimatsu goes to ground, his former ally Masato is ordered to hunt him down. Critique: Miike Takashi’s Graveyard of Honor is perhaps best considered a new adaptation of Goro Fujita’s novel, rather than a remake of Fukasaku’s film – rather like the relationship between The Thing from Another World (Christian Nyby, 1951) and John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982).  Miike’s film follows the same basic narrative as Fukasaku’s adaptation of Goro’s book but moves the story forwards in time, to the 1980s and 1990s. Miike opens his film with a scene set at night in which a jailed Ishimatsu persuades a guard to let him out of his cell in order to dry out his sodden blanket. The guard is initially reticent but complies when Ishimatsu promises to cut him in on an outside deal. Suddenly, with no warning, Ishimatsu pushes the guard down a flight of steps and makes his escape. With this scene, Miike deftly establishes a tone of sudden, casual violence – committed with no anticipation and no afterthought. Miike’s film follows the same basic narrative as Fukasaku’s adaptation of Goro’s book but moves the story forwards in time, to the 1980s and 1990s. Miike opens his film with a scene set at night in which a jailed Ishimatsu persuades a guard to let him out of his cell in order to dry out his sodden blanket. The guard is initially reticent but complies when Ishimatsu promises to cut him in on an outside deal. Suddenly, with no warning, Ishimatsu pushes the guard down a flight of steps and makes his escape. With this scene, Miike deftly establishes a tone of sudden, casual violence – committed with no anticipation and no afterthought.

From here, Miike takes us back in time. A younger Ishimatsu, his hair dyed blonde, is working in a restaurant. A group of hoodlums enter and shoot up the place. Their target is Boss Sawada. Demonstrating a predilection for violence and an aptitude for brutality, rather than any sense of resourcefulness or ingenuity, Ishimatsu jumps into the fray and saves Sawada’s life. In response, Sawada takes Ishimatsu under his wing and elevates him to a senior rank within the Sawada family, much to the chagrin of a number of more seasoned members of the clan. Ishimatsu proves himself to be an uncouth beast – spitting, putting his feet on desks, refusing to take off his sunglasses. Kishitani plays the ‘rabid dog’ Ishimatsu with a similar sense of aloof arrogance (signalled through a similar use of sunglasses) as Watari’s performance as Ishikawa in Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor, but in Miike’s film Ishimatsu’s propensity for unprovoked violence is signalled from the outset, and his descent into utter nihilism seems more inevitable than tragic or pathetic. Kishitani and Watari’s performances are both utterly animalistic – certainly among the most feral of performances in narrative cinema. Always the visual stylist, Miike does not miss any opportunities for aesthetically pleasing grue: Ishimatsu is shown blazing away with a gun behind a cloud of feathers thrown up by torn upholstery, and a gruesome slashing/stabbing takes place on a bed of snow, ink-red blood spraying across the pure whiteness. Early in the film, Ishikawa disembowels a rival gangster, Yamane, in a gambling joint; Ishikawa is ruthless and shows now shame in his enactment of this act of brutality, and wanders the streets afterwards, covered in blood. Ishimatsu turns up on the doorstep of Chieko, demanding that she look after his money whilst he is in prison – and, still covered in Yamane’s blood, rapes her. Or is it rape? Chieko visits Ishimatsu in prison and asks him, ‘What am I to you?’ ‘My wife’, he tells her matter-of-factly. Again, as in Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor, we find a curious relationship in which Chieko follows the cruel Ishimatsu doggedly, apparently utterly devoted to him, and the couple’s sexual interactions look for all intents and purposes like scenes of sexual assault. For Ishimatsu, life – and sex – is cruelty. Coitus for Ishimatsu is always violent. For Chieko, it is subjugation. Ishimatsu and Chieko’s fatalistic love affair (if it can be called love) anchors the narrative – an animalistic attraction predicated on devotion. Ishimatsu is tethered to a particular idea of male behaviour. When his lawyer suggests Ishimatsu should plead that he attempted to wound Yamane rather than kill him, Ishimatsu scoffs at the idea. ‘If I say that, I’ll sound like a pussy’, Ishimatsu rants, ‘I’m a yakuza!’  Where Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor is clearly located in post-war Japan, occupied by US forces, Miike’s take on the same story emphasises its relationship with the aftermath of the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the mid-1980s. Whilst Ishimatsu is in prison for the murder of Yamane, Japan’s economy tanks and, on his release, society is dealing with the fallout from this. ‘Eight years went by’, the narrator tells us when Ishimatsu is released from prison in 1989, ‘The “post-bubble” era brought hard times to the straight world and to the yakuza. Like wolves driven out of the pack, some yakuza were forced out of their families’. The use of simile within the narration is apt: in the post-bubble economy, the yakuza find themselves adrift, disanchored from traditional models of propriety and the hierarchy of their families, like predators set amongst a flock of sheep. Where Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor is clearly located in post-war Japan, occupied by US forces, Miike’s take on the same story emphasises its relationship with the aftermath of the bursting of Japan’s economic bubble in the mid-1980s. Whilst Ishimatsu is in prison for the murder of Yamane, Japan’s economy tanks and, on his release, society is dealing with the fallout from this. ‘Eight years went by’, the narrator tells us when Ishimatsu is released from prison in 1989, ‘The “post-bubble” era brought hard times to the straight world and to the yakuza. Like wolves driven out of the pack, some yakuza were forced out of their families’. The use of simile within the narration is apt: in the post-bubble economy, the yakuza find themselves adrift, disanchored from traditional models of propriety and the hierarchy of their families, like predators set amongst a flock of sheep.

Miike returns several times to a yakuza parable, initially delivered by the voiceover narration but later mentioned in passing in the film’s dialogue: ‘The Godfather went to the dentist with a toothache. In the two hours he was gone, a yakuza walked into hell’. This parable underscores the extent to which the behaviour of the yakuza within the film depends on their subservience to authority: when, as the narration suggests, they are disanchored from the strict hierarchy of their families (such as in the aftermath of the collapse of the economic bubble in the mid/late-1980s), they are set loose upon the world. (‘And what rough beast/Its hour come round at last/Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born’, Yeats wrote.) Within this context, the animalistic behaviour of Ishimatsu makes perfect sense: he embodies an id that is kept in check by the superego embodied in the yakuza through its clear sense of hierarchy. In the absence of clear authority, things fall apart. Violence escalates throughout the narrative – a complex game of one-upmanship which only leads the body count to grow exponentially. The hot-headed Ishimatsu mocks members of his own family, leading him into a direct confrontation with Boss Sawada, who Ishimatsu shoots – but not fatally. As the voiceover narrator tells us, ‘He [Ishimatsu] knew he’s put the wrong button in the wrong hole. But undoing a button once it’s done up is something the yakuza world does not permit’. Ishimatsu seeks refuge by calling on his allies, including Imamura and Narimura; but Ishimatsu’s increasingly self-destructive behaviour alienates his closest allies, with the exception of Chieko. ‘As they are born of women, even yakuza are human beings’, the narrator tells us, ‘And as human beings, they exist as part of a social structure whose rules they must follow. All there is for those who break these rules is the demon’s path: a path of impulse, of continuing to breathe, yet always wandering towards a demon’s death’.

Video

Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku, 1975) Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku, 1975)

Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor runs for 93:38 mins. Photographed on 35mm colour film, Graveyard of Honor is here presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, in a presentation that retains the film’s original aspect ratio of 2.35:1. (The film was shot anamorphically, in Toeiscope.) Like many Japanese widescreen pictures of the early/mid 1970s, Graveyard of Honor’s photography contains some aberrations that would seem to be a product of the characteristics of the anamorphic lenses used during the production (eg, a pin sharp central point of focus that tapers off/vignettes towards the edges of the frame). Though the bulk of the film is presented in colour, Graveyard of Honor mixes black and white stills with sepia-tinted footage in the flashbacks – in service of its semi-documentary aesthetic. The presentation is very good and on par with Arrow’s releases of other Japanese films of this vintage. Contrast levels are very pleasing, with some deep blacks and balanced midtones. The colour palette is also naturalistic and even. The encode to disc presents no problems, with the presentation retaining a very filmlike grain structure. In all, this is as pleasing as Arrow’s other HD releases of Fukasaku’s jitsuroku pictures from this period.  Graveyard of Honor (Miike, 2002) Graveyard of Honor (Miike, 2002)

Running for 130:35 mins, Miike’s Graveyard of Honor is also presented using the AVC codec, and in its original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. This HD presentation is a big improvement over the R1 DVD release from Animeigo. The level of detail is very good, and colours are consistent throughout the presentation. Contrast levels are pleasing, which given the chiaroscuro lighting schemes that are used in the film’s photography, is very pleasing – with some good blacks. It’s a presentation that has a sense of depth to it, but it also has a fairly soft, slightly filtered appearance in places that makes me wonder if the presentation is based on an older master. Either way, the presentation is head and shoulders above the benchmark set by the film’s previous R1 DVD release – which is the DVD release by which most English-speaking viewers will have encountered the film. NB. Some full-sized screengrabs are included at the bottom of this review. Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku, 1974)

Graveyard of Honor (Miike, 2002)

Audio

Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor is presented with a DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 track, in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. The track is rich and deep, with a good sense of range. Miike’s film is presented with a DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 stereo track. Naturally, this sounds more modern than the mono track on the Fukasaku picture. Again, it has a pleasing sense of depth and range to it. In the case of both films, the optional English subtitles are easy to read and contain no glaring errors.

Extras

Disc contents are as follows:  DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku, 1975) - Audio commentary by Mark Schilling. Schilling talks about the relationship between Fukasaku’s film and the real-life story that inspired it. He discusses the scripting of the picture and how it evolved into what Schilling describes as a ‘psychological portrait’ of Ishikawa. - ‘Like a Balloon: The Life of a Yakuza’ (13:11). Mike White, of Cashiers du Cinemart, narrates a video essay about Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor. White demonstrates his research into the paradigms of the yakuza picture and discusses how the sub/genre of yakuza films evolved during the 1960s and 1970s. He considers the origins of Graveyard of Honor and its similarities with Fukasaku’s Street Mobster. White also reflects in some detail on Fukasaku’s technique and his approach to constructing a semi-documentary aesthetic. - ‘A Portrait of Rage’ (19:46). Described as ‘an archival appreciation of Fukasaku’, this piece features interviews with Fukasaku’s collaborators, including his son Kenta, and fans of the filmmaker alike. Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘On the Set with Fukasaku’ (5:34). Oguri Kenichi, the assistant director of Graveyard of Honor, speaks about working on the picture with Fukasaku. - Trailer (3:31). - Image Gallery (4:40).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

Graveyard of Honor (Miike, 2002) - Audio commentary by Tom Mes. Mes provides a characteristically thorough commentary for Miike’s version of Graveyard of Honor, which opens with a discussion of Miike’s picture’s relationship with the Fukasaku film and the true story on which both movies are based. He discusses the importance of the updated setting of the Miike film, considering the relationship between the yakuza and the corporate world – and how this is an undercurrent of Miike’s gangster films, with Miike’s protagonists representing a sense of freedom against this stifling corporatisation of culture. - ‘Men of Violence: The Male Driving Forces in Takashi Miike’s Cinema’ (23:46). Kat Ellinger narrates a video essay looking at Miike’s Graveyard of Honor in the context of the period of Miike’s career that followed in the wake of his international ‘breakthrough’ with Audition. Ellinger establishes a dualism between the more outrageous violence of Miike’s films like Ichi the Killer and what she suggests is a more ‘realistic’ approach to violence in Graveyard of Honor, and argues that the film is an outlier in terms of Miike’s body of work. (There’s a debate that could be held about the extent to which Miike’s Graveyard may be considered ‘realistic’ – or simply stylised in a way which feels less outrageously stylised.) In discussion the film’s depiction of a rogue male, Ellinger attempts to connect Miike’s depiction of Ishimatsu with various works by American gangster filmmakers (eg, De Palma’s Scarface, Scorsese’s Goodfellas). She underscores her discussion of Graveyard of Honor through reference to Tom Mes’ book Agitator and his identification of the six traits that, Mes claims, are indices of Miike’s authorial voice. - Interview Special (17:59). In this vintage featurette, Miike, Arimori and Kishitani talk about Miike’s Graveyard of Honor. Particularly interesting are Miike’s comments about his methods in capturing the volatility of the character of Ishimatsu – including careful attention to the hairstyles of the character. Kishitani offers some very thoughtful insight into his approach to the role – redefining his sense of ‘normality’ in order to capture Ishimatsu’s skewed perception of what is acceptable behaviour and what isn’t. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Making of Featurette (8:02). Essentially a montage of behind the scenes footage with interviews, this featurette was produced to promote the film. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Making of Teaser (2:14). This is a promotional piece containing some behind the scenes footage. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Press Conference (4:17). Miike, Kishitani and Arimori speak to an audience about the film, Miike explaining that his film should not be compared with Fukasaku’s picture – they are very different films. The actors talk about their respective roles. Japanese with optional English subtitles. - Premiere Special (4:03). Miike, Kishitani and Arimori speak onstage at the film’s premiere, introducing the film - Trailer (1:39). - Image Gallery (0:50).

Overall

‘What turned this young man into a rabid dog? Was it the chaos and confusion of the post-war years?’, the offscreen interviewer in Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor asks, in reference to Ishikawa. Though quite different films set in very different contexts (post-war Japan versus the post-bubble Japan of the late 1980s/90s), Fukasaku and Miike’s versions of Graveyard of Honor are linked by the manner in which they both focus on a yakuza who finds himself kicking against the pricks – battling against the constrictive behavioural paradigms of the organisation in which he becomes absorbed. ‘What turned this young man into a rabid dog? Was it the chaos and confusion of the post-war years?’, the offscreen interviewer in Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor asks, in reference to Ishikawa. Though quite different films set in very different contexts (post-war Japan versus the post-bubble Japan of the late 1980s/90s), Fukasaku and Miike’s versions of Graveyard of Honor are linked by the manner in which they both focus on a yakuza who finds himself kicking against the pricks – battling against the constrictive behavioural paradigms of the organisation in which he becomes absorbed.

At end of Fukasaku’s film, the narration states that ‘As the prototype of the post-war yakuza, his name lives on in legend today’. Certainly, Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor helped to consolidate its director’s semi-documentary approach, which had been established in some of Fukasaku’s earlier films (including Street Mobster), which is followed through by Miike’s Graveyard of Honor. In both pictures, but particularly in Miike’s film, the violence in particular is both naturalistic and heavily stylised. This writer will make no bones about the fact that since I first encountered it, Miike's Graveyard of Honor has worked its way into my list of 20 favourite films, so I'm ecstatic to see it get a Blu-ray release. Fukasaku's original is also one of its director's most memorable pictures. The hoary old cliche in screenwriting that scripts shouldn't revolve around unpleasant people doing unpleasant things is thoroughly disproved by both Miike and Fukasaku's versions of this story. Ishikawa/Ishimatsu is a thorough shit who is adrift in an unimaginably cruel world. Both films' protagonists' behaviour, especially towards Chieko (and the other women in the films), offers a challenge to prevailing contemporary popular critical discourse which sometimes naively confuses depiction of a character's attributes/worldview with the endorsement of the same. Both Fukasaku’s Graveyard of Honor and Miike’s re-imagining are excellent films whose appearance on the Blu-ray format is very welcome. Arrow’s HD presentations of both films are very good, and both pictures are supported by some excellent contextual material. References: Desjardins, Chris, 2005: Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film. London: I B Tauris Jacoby, Alexander, 2008: A Critical Handbook of Japanese Film Directors: From the Silent Era to the Present Day. California: Stonebridge Press Sharp, Jasper, 2011: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema. Maryland: Scarecrow Press Taylor-Jones, Kate E (2013): Rising Sun, Divided Land: Japanese and South Korean Filmmakers. London: Wallflower Press Varese, Federico, 2018: Mafia Life: Love, Death and Money at the Heart of Organized Crime. Oxford University Press Please click to enlarge. Graveyard of Honor (Fukasaku, 1975)

Graveyard of Honor (Miike, 2002)

|

|||||

|