|

|

The Film

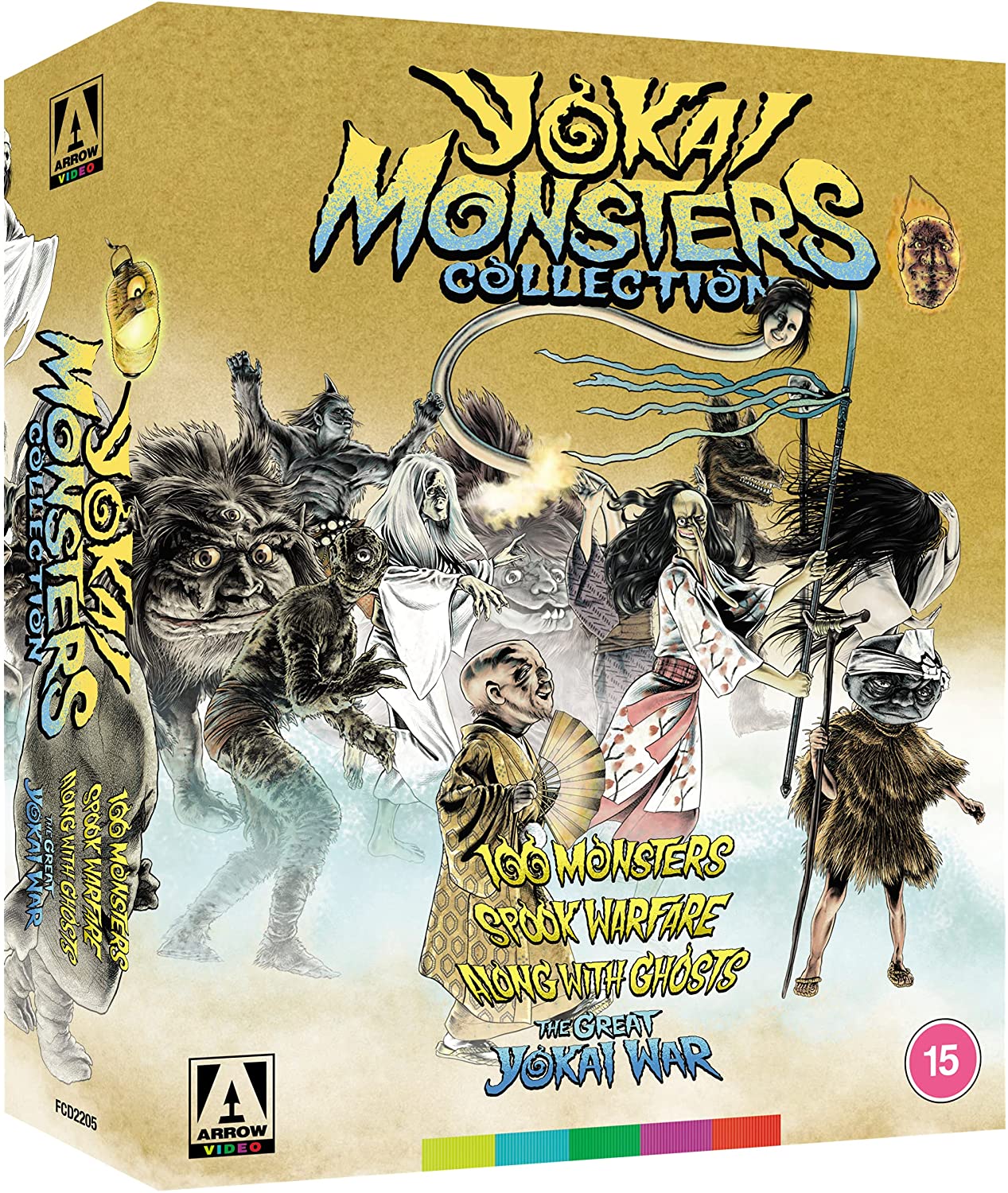

The Yokai Monsters Collection The Yokai Monsters Collection

The three ‘vintage’ films in Arrow’s set represent a semi-official triptych of narratives focusing on yōkai: spirits of Japanese folklore. In truth, Japanese cinema is filled with yōkai; and though in these three films yōkai are billed as ‘monsters’, they are anything but: in folklore, they may be benign or malevolent, though they are mostly playful; they may be corporeal or ethereal; and they may be distinctly humanoid or with animal characteristics. (For example, the second film in this series, Spook Warfare, features a key role for the kappa, a yōkai that is represented in this film as a humanoid being with certain amphibian-like characteristics, such as the ability to leap like a frog or toad.) In fact, in the films contained in this loose trilogy, the yōkai are almost wholly positive in their influence, agents for justice who aid humans in need – who are being railroaded by greedy landowners (100 Monsters), or pursued relentlessly by murderous hoodlums (Along with Ghosts). Arrow’s set also includes a more recent yōkai picture, Miike Takashi’s The Great Yōkai War (2005), which is actually a loose remake of the second yōkai picture from the 60s (Spook Warfare). A sequel to Miike’s film has recently (as of late 2021) been released in Japan, directed by Miike and entitled The Great Yōkai War: Guardians. Synopses  Yōkai Monosters: 100 Monsters (Yasuda Kimiyoshi, 1968) Yōkai Monosters: 100 Monsters (Yasuda Kimiyoshi, 1968)

Tajimaya (Kanda Takashi), in league with Lord Buzen of Hotta (Gomi Ryutaro), plots to exploit a debt owed to him by the village elder Jinbei (Hanabu Tatsuo), in order to tear down a tenement and its accompanying shrine. Tajimaya and Buzen aim to profit from the sale of the land. Tajimaya uses brute force to displace the tenants, his men beating and ultimately causing the death of Gohei (Hamamura Jun), the caretaker. Tajimaya invites Buzen to an evening of the ‘100 Monsters’: tellings of one hundred stories of yōkai, which must be ended with a specific ritual – or else, a curse will be enacted upon then listeners. Sneering at the idea of a curse, the cocky Tajimaya insists that the completion ritual not be conducted. This, of course, invites disaster for Tajimaya, who finds his actions against the tenement, and its occupants, thwarted by both yōkai and a mysterious stranger named Yasutaro (Fujimaki Jun).  Yōkai Monsters: Spook Warfare (Kuroda Yoshiyuka, 1968) Yōkai Monsters: Spook Warfare (Kuroda Yoshiyuka, 1968)

Two bumbling British archaeologists unleash an ancient demon, Daimon, during their dig in the ruins of Ur, an ancient city of Babylonia. Daimon makes headway towards Japan, where he/it ‘possesses’ (or, more accurately, mimics and replaces) Kappa, a water spirit resembling an amphibian, recognises that something is awry. He informs the other yōkai. They are skeptical at first but, observing the humans, come to recognise Daimon’s influence. Working with Shinhachiro (Aoyama Yoshihiko), the yōkai endeavour to rid Japan of the cruel Daimon.  Yōkai Monsters: Along with Ghosts (Kuroda Yoshiyuka & Yasuda Kimiyoshi, 1969) Yōkai Monsters: Along with Ghosts (Kuroda Yoshiyuka & Yasuda Kimiyoshi, 1969)

The elderly priest Jinbel is attacked by a group of hoodlums, headed by the ruthless Higuruma (Yamaji Yoshindo), after Jinbel interrupts the gang’s murder of a courier who is carrying a document that incriminates Higuruma in various illegal shenanigans. Jinbel warns Higuruma and his compadres that spilling blood on the land will result in a curse; Higuruma responds by assaulting the elderly priest. Jinbel is mortally wounded but manages to escape, however, and return to his shack, where he warns his young granddaughter, Miyo (Burukido Masami), to flee to the town of Yui, and make contact with her father, Tohichi, who left after Miyo’s mother died in childbirth. However, Miyo is pursued by Huguruma and his gang, who intend to kill the child in order to seize control of the document, of which she is in possession. However, Miyo finds an unlikely ally in wandering samurai Hyakusaro (Hongo Kojiro) and various yōkai, determined to carry out the curse of which Jinbel warned Higuruma.  The Great Yōkai War (Miike Takashi, 2005) The Great Yōkai War (Miike Takashi, 2005)

Young Tadashi (Kamiki Ryunosuke) lives with his mother and grandmother in a village. His sister and father, who is divorced from Tadashi’s mother, live in Tokyo. At a village festival, Tadashi is picked during a Dragon Dance as the Kirin Rider. Legend tells that the Kirin Rider is the only one who can retrieve the Goblin Sword from the mountain that overlooks the village, and this Goblin Sword will allow the Kirin Rider to vanquish the forces of darkness in the region. Meanwhile, the sinister Lord Kato (Toyokawa Etsushi), aided by a sadistic yōkai named Agi (Kuriyama Chiaki), has a number of yōkai held captive in his huge industrial factory. Kato is transforming these yōkai into robots, with the aim of constructing an army of metal beasts with which he intends to plunge humanity into darkness. Tadashi encounters a cute hamster-like yōkai, Sunekosuri, and decides to venture out to the Goblin Mountain, to see if the legend is true. He teams up with other yōkai, including a kappa and Kawahime, the River Princess (Iwaido Seiko). They venture to Lord Kato’s lair, in order to free the captured yōkai and despatch Kato and Agi.  Critique Critique

Largely unseen outside Japan (prior to this home video release by Arrow, that is), the three ‘vintage’ yōkai films in this set were written by Yoshida Tetsurō for Daiei Film, and intended as child-friendly pictures. Set during the Edo period, Tetsurō’s scripts were based on the folk tales of Momotarō, the hero of Japanese folklore, and apparently inspired by the manga of Mizuki Shigeru. (Shigeru makes a cameo in Miike’s The Great Yōkai War.) Each of the films has a deeply moral dimension. In 100 Monsters, the real ‘monsters’ are the grasping landowners, Tajimaya and Buzen, who plot to tear down the tenement and the shrine next to it, their actions leading to the death of the elderly caretaker, Gohei, after he is assaulted by Tajimaya’s hoodlums. When Yasutaro hears of Tajimaya’s ‘100 Monsters’ soiree, he comments, dryly, ‘The One Hundred Stories? How fitting for a bunch of monsters possessed by greed’. The wealthy, it seems, are able to obscure their misdemeanours (and more serious crimes): after Tajimaya has Jinbei murdered, Daikichi (another tenant in the tenement) observes that ‘He [Tajimaya] can cover up something that takes place in front of our own eyes’. At the end of the film, after defeating this most inhuman of enemies (self-interest and greed), the diverse yōkai celebrate with a dance which, on a scale of cuteness, is on par with the Ewok celebration at the end of Richard Marquand’s Return of the Jedi (1983). (In other words, one will either love it unashamedly, or the more cynical will find it to be deeply, profoundly, irritating.) This establishes a template for the final scenes of the other films in this loose series of pictures.  One of the delights of the first two films in particular, is the comical appearance of a specific tsukumogami: an object animated by a spirit. In this case, the object is a one-legged, hopping umbrella with a ludicrously long tongue, who in 100 Monsters playfully uses this appendage to tickle the cheek of Shinkichi, the half-witted son of Tajimaya. (The umbrella spirit appears frequently in Japanese folklore, and has been named the kasa-obake.) Shinkichi ‘conjures’ the kasa-obake by drawing it on the walls of a room in his family’s house, and the kasa-obake comes to life in, firstly, still-frame animation, and then via puppetry. The kasa-obake also makes a brief appearance in The Great Yōkai War: when Tadashi and the small band of yōkai with which he is allied propose making an assault on Lord Kato’s headquarters, kasa-obake protests meekly that he is ‘just an umbrella’ – before calling on his friend, a walking wall that similarly protests that he is but a wall, and what can he do to combat Kato and his minions? One of the delights of the first two films in particular, is the comical appearance of a specific tsukumogami: an object animated by a spirit. In this case, the object is a one-legged, hopping umbrella with a ludicrously long tongue, who in 100 Monsters playfully uses this appendage to tickle the cheek of Shinkichi, the half-witted son of Tajimaya. (The umbrella spirit appears frequently in Japanese folklore, and has been named the kasa-obake.) Shinkichi ‘conjures’ the kasa-obake by drawing it on the walls of a room in his family’s house, and the kasa-obake comes to life in, firstly, still-frame animation, and then via puppetry. The kasa-obake also makes a brief appearance in The Great Yōkai War: when Tadashi and the small band of yōkai with which he is allied propose making an assault on Lord Kato’s headquarters, kasa-obake protests meekly that he is ‘just an umbrella’ – before calling on his friend, a walking wall that similarly protests that he is but a wall, and what can he do to combat Kato and his minions?

The second picture in the series, Spook Warfare, features a more foregrounded role for the yōkai in the narrative. Where 100 Ghosts and Away With Ghosts focus on human characters, the yōkai appearing in the background of each films’ respective narrative to assist humans who find themselves in perilous situations, in Spook Warfare the yōkai – and particularly the aforementioned kappa – are at the heart of the plot. They recognise the threat represented by Daimon, the demon who is released by klutzy British archaeologists digging in the Babylonian city of Ur and who travels to Japan, possessing (or rather, duplicating) Lord Isobe; and it is the yōkai who come up with a plan to dispel Diamon. The British archaeologists in this film’s opening sequence represent the nefarious foreign influences that so many examples of mid-60s Japanese pop cinema either gently mocked or mercilessly criticised. The uncovering of an ancient evil during an archaeological dig, which then journeys oversees to ‘possess’ an individual, in pursuit of a selfish plan, seems to anticipate William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) – though probably looks backwards to Karl Freund’s The Mummy (1932) and its various other iterations. If the British archaeologists represent a bumbling and incompetent foreign influence, Daimon represents a much more malign foreign presence. ‘If we leave the likes of him [Daimon] alone’, one of the yōkai comments in reference to Daimon, ‘shame will be brought on Japanese apparitions’.  However, the use of the word ‘possess’ in this instance is slightly inaccurate. In its dialogue, Spook Warfare is careful to emphasise that Daimon does not ‘possess’ his victims but instead eradicates them and replaces (or mimics) them. Thus someone who has been ‘duplicated’ by Daimon cannot be returned to the mortal realm: they are dead and gone, forever. The intensity of Daimon’s plan is amplified when, part-way through the picture, it becomes apparent that the demon needs to build his strength by drinking the blood of children(!) However, the use of the word ‘possess’ in this instance is slightly inaccurate. In its dialogue, Spook Warfare is careful to emphasise that Daimon does not ‘possess’ his victims but instead eradicates them and replaces (or mimics) them. Thus someone who has been ‘duplicated’ by Daimon cannot be returned to the mortal realm: they are dead and gone, forever. The intensity of Daimon’s plan is amplified when, part-way through the picture, it becomes apparent that the demon needs to build his strength by drinking the blood of children(!)

Spook Warfare features a high quota of yōkai, including the return of the kasa-obake and rokurobuki (long-necked female spirit) from 100 Monsters, alongside the kappa and a key role for the futakuchi-onna (a female spirit, with a second face that is horrific – somewhat resembling the Roman god Janus) and the nuppeppō (a sort of formless blob of clay, with stumpy arms and legs). When a plan to use magic to dispel Daimon backfires, trapping a number of yōkai – including the kappa – in a jar, only the kasa-obake and futakuchi-onna remain free, and they are tasked with seeking assistance from the humans in order to free their comrades. The yōkai form a community of outcasts: initially frightening, or at least disquieting, in their appearance but ultimately benign. With its ad-hoc community of monsters, diverse in appearance and mannerisms, one wonders whether Clive Barker’s conceptualisation of Midian, the home of the Nightbreed, in his novel Cabal and its film adaptation (Nightbreed) was inspired by stories of the yōkai – particularly as they are represented in Spook Warfare, banding together against a common enemy. The parallels between Cabal and the yōkai seem even more apparent when watching Miike’s The Great Yōkai War, which features numerous scenes in which the ragtag bunch of spirits and sprites stage meetings with the intention of devising a plan to confront Lord Kato.  Miike’s The Great Yōkai War seems particularly timely in its juxtaposition of the rural with the urban/industrial, and its emphasis on Lord Kato’s lair as a huge industrial complex spraying pollution into the atmosphere. Kato’s minions are robots, and Kato transforms captured yōkai into these mechanical monstrosities by dropping them into a furnace. Like the yōkai pictures of the 60s, seems clearly intended for a family audience; and in its focus on a child who goes on a marvelous adventure with a band of magical playmates, The Great Yōkai War feels like the kind of family film Hollywood excelled in making during the 1980s but which has in the 21st Century neglected. However, there are some moments which push the boundaries of what is acceptable for a child audience. The shots of yōkai burning in Kato’s huge furnace are challenging, as are the handful of scenes in which Tadashi’s cute ally Sunekosuri is on the receiving end of some quite brutal violence. Miike’s The Great Yōkai War seems particularly timely in its juxtaposition of the rural with the urban/industrial, and its emphasis on Lord Kato’s lair as a huge industrial complex spraying pollution into the atmosphere. Kato’s minions are robots, and Kato transforms captured yōkai into these mechanical monstrosities by dropping them into a furnace. Like the yōkai pictures of the 60s, seems clearly intended for a family audience; and in its focus on a child who goes on a marvelous adventure with a band of magical playmates, The Great Yōkai War feels like the kind of family film Hollywood excelled in making during the 1980s but which has in the 21st Century neglected. However, there are some moments which push the boundaries of what is acceptable for a child audience. The shots of yōkai burning in Kato’s huge furnace are challenging, as are the handful of scenes in which Tadashi’s cute ally Sunekosuri is on the receiving end of some quite brutal violence.

The films feature some incredible special effects work: combined with carefully-characterised performances by the actors playing the yōkai, the spirits are articulated onscreen via a mixture of puppetry, costumes, some super prosthetics work, and stop frame animation, together with photographic tricks including multiple exposures. Miike’s 2005 picture supplements these techniques with some showy digital effects work.

Video

All three of the ‘vintage’ yōkai films were shot in 35mm, on Fuji stock and in Daieiscope, an anamorphic process. On this release, they are presented in their intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. All three films are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec. All three of the ‘vintage’ yōkai films were shot in 35mm, on Fuji stock and in Daieiscope, an anamorphic process. On this release, they are presented in their intended aspect ratio of 2.35:1. All three films are presented in 1080p using the AVC codec.

Disc One contains Yōkai Monsters: 100 Monsters. With a running time of 78:47 mins, the film fills 21.4Gb of space on the disc. Disc Two contains Yōkai Monsters: Spook Warfare (78:57 mins / 20.7Gb) and Yōkai Monsters: Along with Ghosts (78:15 mins / 20.6Gb). The presentations of all three films are very similar, so it seems fair to discuss them together. The level of detail is pleasing throughout, with fine detail present in close-ups. Contrast levels are very good, with a pleasing curve to the toe and shadow detail present. Highlights are protected and evenly-balanced throughout the three presentations. Colours are consistent and naturalistic throughout. The encodes to disc present no apparent problems, the presentations retaining a very film-like grain structure, as befitting the source material. The anamorphic lenses used in the productions demonstrate some noticeable aberrations towards the edge of the frame, which are more obvious in some shots and under certain lighting. There is some minor evidence of print damage: some vertical scratches (in 100 Monsters) and white flecks and specks (most noticeable in Along with Ghosts) but always fleeting and nothing too distracting. In sum, all three of these films have excellent, film-like presentations on these discs.  Disc Three contains Miike Takashi’s The Great Yōkai War (124:10 mins / 31.4Gb). This is the full-length cut of the film. (An abbreviated version of the picture, shorn of around 20 minutes, seems also to have been screened.) This film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film was apparently shot in a 35mm spherical process, but the abundance of digital effects in the picture (including digital backgrounds and compositing) gives the film an analogue-digital hybrid aesthetic in terms of colour and light (if not in terms of the structure of the image). The grain structure of 35mm film is present throughout, and detail levels are superb. Contrast levels are also pleasing, with some careful gradation into both the toe and the shoulder of the exposure. In all, it’s a superb presentation of the film. Disc Three contains Miike Takashi’s The Great Yōkai War (124:10 mins / 31.4Gb). This is the full-length cut of the film. (An abbreviated version of the picture, shorn of around 20 minutes, seems also to have been screened.) This film is presented in 1080p, using the AVC codec, and in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The film was apparently shot in a 35mm spherical process, but the abundance of digital effects in the picture (including digital backgrounds and compositing) gives the film an analogue-digital hybrid aesthetic in terms of colour and light (if not in terms of the structure of the image). The grain structure of 35mm film is present throughout, and detail levels are superb. Contrast levels are also pleasing, with some careful gradation into both the toe and the shoulder of the exposure. In all, it’s a superb presentation of the film.

Some full-sized screengrabs from all three films are included at the bottom of this review. Please click these to enlarge them.

Audio

On its disc, 100 Monsters is presented with a LPCM 1.0 mono track, in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. On Disc Two, Spook Warfare and Along with Ghosts are both presented with Japanese language DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 tracks, again with optional English subtitles. The audio tracks for all three films demonstrate pleasing range and depth, with strong Disc Three contains The Great Yōkai War, with a number of audio options. The film is presented with: (i) a Japanese DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 track; (ii) a Japanese LPCM 2.0 track; (iii) an English-DTS HD Master Audio 5.1 track. The English dub is serviceable, but the Japanese tracks are, naturally, more organic in terms of the material. The 5.1 track offers a much broader, more immersive soundscape, thanks to the surround effects, and is arguably the way to go: but both Japanese tracks demonstrate excellent fidelity, with impressive range and depth in terms of the sound effects and music. Optional English subtitles translating the Japanese dialogue are provided, and these are easy to read and grammatically correct.

Extras

The disc contents are as follows:  DISC ONE: DISC ONE:

- Yōkai Monsters: 100 Monsters - ‘Hiding in Plain Sight: A Brief History of Yōkai’ (41:11). This is a documentary looking at depictions of yōkai in cinema. It contains contributions from a diverse group of film critics and fans of these films, including Matt Alt, Zack Davisson, Kim Newman, Linda E Rucker, and Hiroko Yoda. The contributors attempt to define what yōkai are, through references to Eurocentric definitions of monsters, ghosts, and spirits: Kim Newman says that the yōkai challenge boundaries between corporeal monsters and ethereal spirits. The literary and folkloric origins of yōkai are examined, leading to a discussion of the films in this set. The documentary is an excellent ‘primer’ on the concept of yōkai, their origins, and their evolution. - Theatrical Trailer (2:16). - US Re-Release Trailer (1:08). - Image Gallery (21 frames).  DISC TWO: DISC TWO:

- Yōkai Monsters: Spook Warfare - Yōkai Monsters: Along with Ghosts - Theatrical Trailers: Spook Warfare (2:12); Along with Ghosts (2:13). - US Re-Release Trailers: Spook Warfare (1:55); Along with Ghosts (1:19). - Image Galleries: Spook Warfare (16 frames); Along with Ghosts (14 frames).  DISC THREE: DISC THREE:

- The Great Yōkai War - Audio commentary by Tom Mes. Mes, the author of the excellent Agitator: The Cinema of Takashi Miike, discusses The Great Yōkai War. Mes suggests that The Great Yōkai War is seen as the ‘starting point’ of a shift in Miike’s career, away from the cult oddities he had previously helmed and towards more mainstream, often family-friendly films with much larger budgets. Mes argues that this ‘turn’ originated with the previous year’s Zebraman and One Missed Call – the latter being Miike’s first ‘bona fide mainstream hit’. Mes is always an articulate and insightful commentator on Miike’s pictures, and this commentary track is no exception to this. - Cast Interviews: o Miyasako Hiroyuki (Sada) (5:42). o Kondo Masaomi (Shoujou) (5:59). o Abe Sadao (Kawataro) (6:41). o Takahashi Mai (Kawahime) (6:44). o Okamura Takashi (Azuki-arai) (6:14). o Sugawara Bunta (Shuntaro Ino) (4:44). o Kuriyama Chiaki (Agi) (6:28). o Imawano Kiyoshiro (Nurarihyon) (3:20). o Toyokawa Etsushi (Lord Kato) (4:48). These interviews are brief but often witty (eg, with the interviewees responding as if in character). The interviewees speak from the set of the film, mostly in costume and makeup. (A notable exception to this is Kuriyama, who appears here sans the makeup for her character, Agi.) The segment with Kiyoshiro Imawano features footage of the major prosthetic makeup effects being applied to the actor. Comments from the interviewees are interspersed with behind the scenes footage of the production. The cast members talk about their careers and working with Miike, and the rigours of performing in a Miike-directed feature. The interviews, shot on video, are in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Crew Interviews: o Miike Takashi (12:16). o Inoue Junya (creature design) (5:52). o Hyakutake Tomo (creature design and molding) (4:25). o Matsui Yuichi (yōkai makeup) (4:25). o Sasaki Hisashi (art direction) (4:24). o Nirasawa Yasushi & Takeya Takayuki (creature design) (3:30). o Otagaki Kaori (CGI director) (6:27). The crew discuss their respective roles in the production. Miike’s interview is the most interesting. The director talks about the fairly lengthy gestation and development of the project, and how, despite his feelings that he might get tired of the subject, the project maintained his interest throughout. Miike also talks about his respect for the performers in the film, particularly Sugawara and Sadao. The other participants discuss the special effects, including prosthetics and makeup effects. The interviews are in Japanese, with optional English subtitles, and are, like the cast interviews, shot on video. - Short Drama of Yōkai: ‘Whose Hotcakes are These?’ (6:03); ‘Who’s the Most Annoying?’ (7:45). These are short, humorous ‘skits’ about yōkai, shot on video and presumably intended for television broadcast. They feature performers in simple face masks. They are in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Another Story of Kawatoro’: Part One (6:32); Part Two (10:25). These shorts, also filmed on video, feature performers in their makeup for the main feature, and they revolve around Kawatoro, the kappa in the film. They are in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - World Yōkai Conference (13:07). This is a stage event, filmed on video, featuring members of the cast and crew – including Miike – talking about the picture in front of a live audience. Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Promotional Events: Announcement Event (7:40); Press Conference (3:43); Premiere (6:09). Again, these are events promoting the film, with the cast and crew appearing on stage in front of a live audience. Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - ‘Documentary of Ryunosuki Kamiki’ (27:19). This opens with the screening of Miike’s film at the 62nd Venice Film Festival, before taking us back to the production of the picture. The documentary focuses on Kamiki’s role in the production, and his performance as Tadashi, the ‘Kirin Rider’. Shot on video, the documentary is presented in Japanese, with optional English subtitles. - Theatrical Trailer (1:44). - Image Gallery (23 frames).

Overall

This boxed set release from Arrow is excellent fun. The three vintage yōkai films are enormously entertaining, though the interconnection between the three is very loose (other than the overlapping appearance of various yōkai within them). There’s an odd shifting of focus from human characters to the yōkai within them, and viewed as family films – which is their original intention – there are moments that one may shy away from showing to younger children. But the films have a strong moral centre, which is carried on to Miike Takashi’s more recent The Great Yōkai War. As Tom Mes says in the commentary on this release, this film is essentially a ‘boy’s own’ adventure story, which focuses on family ties that are broken and must be repaired or overcome. The Miike picture is lengthy – perhaps a little too long – but has enormous, bounding energy: again, it’s a family film, but there are some quite dark and challenging moments within it. (That’s not to say that family films shouldn’t include dark and challenging moments or ideas, of course.) As Mes says, the film is often seen as representing a paradigmatic shift in Miike’s career, towards more mainstream films with larger budgets. This boxed set release from Arrow is excellent fun. The three vintage yōkai films are enormously entertaining, though the interconnection between the three is very loose (other than the overlapping appearance of various yōkai within them). There’s an odd shifting of focus from human characters to the yōkai within them, and viewed as family films – which is their original intention – there are moments that one may shy away from showing to younger children. But the films have a strong moral centre, which is carried on to Miike Takashi’s more recent The Great Yōkai War. As Tom Mes says in the commentary on this release, this film is essentially a ‘boy’s own’ adventure story, which focuses on family ties that are broken and must be repaired or overcome. The Miike picture is lengthy – perhaps a little too long – but has enormous, bounding energy: again, it’s a family film, but there are some quite dark and challenging moments within it. (That’s not to say that family films shouldn’t include dark and challenging moments or ideas, of course.) As Mes says, the film is often seen as representing a paradigmatic shift in Miike’s career, towards more mainstream films with larger budgets.

The presentations of all three films are excellent, though of course Miike’s film, with its heavy emphasis on CGI effects, has a markedly different aesthetic to the three vintage yōkai pictures on discs one and two. The documentary about the yōkai phenomenon on disc one is illuminating for viewers unfamiliar with this paradigm in Japanese cinema, and Miike’s pictures is accompanied by a huge array of contextual material. (Some of this overlaps and becomes a little repetitive when watched back-to-back, admittedly, but nevertheless it’s always illuminating and represents superb value for money.) Please click to enlarge: 100 Monsters

Spook Warfare

Along with Ghosts

The Great Yōkai War

|

|||||

|