|

|

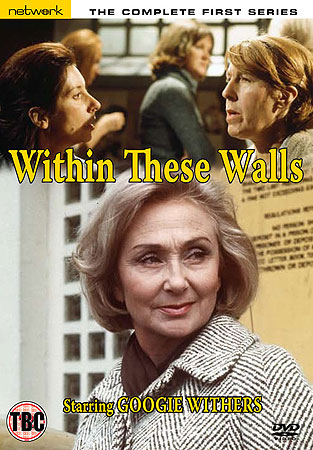

Within These Walls: The Complete First Series (TV)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (14th February 2009). |

|

The Show

Within These Walls (LWT, 1973)

The themes of imprisonment, redemption and punishment offered by prisons have long fascinated authors, dramatists and filmmakers. The genre of prison literature has a long-standing heritage of being engaged with social issues, especially those relating to the relationship between the individual and society. For many people, this aspect of prison narratives is most explicitly embodied in Charles Dickens’ work, especially Great Expectations (1861); but these themes are at the heart of many other examples of prison literature, from Jack London’s The Star Rover (1915) and Elmore Leonard’s Forty Lashes Less One (1972) to Edward Bunker’s The Animal Factory (1977). As a consequence, the genre of prison literature has acquired a reputation as a genre of direct social engagement: in Great Expectations, Dickens ironically alludes to both the penal reform that took place during the 1850s and the riots that occurred at Chatham Convict Prison in 1861 (when prisoners revolted over their diet) when, in chapter 32, the narrator Pip visits Newgate Prison and observes that ‘At that time, jails were much neglected, and the period of exaggerated reaction consequent on all public wrong-doing – and which is always its heaviest and longest punishment – was still far off. So, felons were not lodged and fed better than soldiers (to say nothing of paupers), and seldom set fire to their prisons with the excusable object of improving the flavour of their soup’. In Twentieth Century film and television, prison narratives have often inspired controversy, from The Big House (George W. Hill, 1930), Hollywood’s first prison movie and one of the first ‘big’ talking pictures, and I Am a Fugitive From a Chain Gang (Mervyn LeRoy, 1932) to the HBO series Oz (1997-2003). However, despite the popularity of prison-based films, relatively few television series have been situated within the context of a prison environment, with notable exceptions including Dick Clement and Ian La Frenais’ sitcom Porridge (BBC, 1974-7), Alan Clarke’s highly controversial one-off drama Scum (BBC, 1977), Bad Girls (Shed Productions, 1999-2006), Buried (Channel 4, 2003), the Australian series Prisoner: Cell Block H (Network Ten, 1978-86) and the aforementioned Oz. In the book Law and Justice as Seen on TV (2003), Elayne Rapping notes that the representation of prisons in cinema and television has, during the late Twentieth Century (and early Twenty-First Century), come ‘full circle’: early prison films such as The Big House tended to focus on the brutality of prison life, but during the mid-Twentieth Century prison movies often shifted their focus onto examining the ‘corrective’ elements within the penal system (74). However, contemporary representations of imprisonment and incarceration have once again returned to a focus on brutality and exploitation. Discussing Oz, Rapping suggests that the series ‘turns away from the model of a publicly invisible, benign and “corrective” form of punishment […] to something much more resonant of earlier eras in which punishment […] was not only physical and brutal, but also publicly visible: a ritualistic spectacle that served both as a warning and as a moral education for a public socialized to see crime in terms of evil, of unforgivable and unacceptable social transgressions’ (ibid.).

In these narratives, prison is often offered as a microcosmic representation of society, a distillation of society’s antagonisms and friendships, its uses of power and authority and its exploitation of labour. The prison setting offers a closed world, a controlled environment that is an ideal context for examination of issues of dehumanisation, rebellion, obedience and authority. Where post-war prison films such as The Boys in Brown (Montgomery Tully, 1949) showed prisons as a space in which positive social reform could take place, as noted by Rapping more modern prison narratives tend to adopt a more cynical perspective, focusing instead on the ways in which ‘the system’ brutalises and manipulates both the prisoners and their guards. The 1970s were a transitional period for prison narratives, and during this period the issue of social reform within prisons was placed in tension with more exploitative elements. Both of these can be discerned in Within These Walls. Produced for London Weekend Television in 1973 and lasting for five series (with the last series broadcast in 1978), Within These Walls is set in Stone Park, a women’s prison. The majority of prison narratives revolve around the incarceration of men, although in the 1970s the growth of the WIP (Women-In-Prison) film subgenre redressed that balance; but still, the WIP films were made for a predominantly male audience, and the genre itself was disreputably exploitative. American films such as The Big Doll House (Jack Hill, 1971) and the various European WIP pictures from filmmakers such as Jess Franco (Frauengefängnis/Barbed Wire Dolls, 1975; Frauen für Zellenblock 9/Women in Cell Block 9, 1977) offered a less-than-progressive account of women’s prisons, featuring a litany of exploitative paradigmatic elements that included ritualistic nudity, sadistic punishment, the obligatory ‘hosing down’ of the female prisoners and omnipresent catfights. In contrast to this, British cinema had for several decades attempted to develop a ‘serious’ approach to narratives of women’s prisons. The iconic elements of this type of ‘respectable’ Women-In-Prison picture were defined by J. Lee Thompson’s 1954 film The Weak and the Wicked. Based on an autobiographical account of life in a women’s prison, The Weak and the Wicked established the subgenre’s reliance on a female ensemble cast; by contrast, narratives of male incarceration often (but not always) feature a character who is defined as the protagonist, such as Burt Lancaster’s leading role in Jules Dassin’s Brute Force (1947). The Weak and the Wicked also introduced the women’s prison film’s focus on ‘deviant’ femininity: in other words, the subgenre is often preoccupied with women who are seen as deviant for their adoption of male traits or for their abandonment of traditional female roles. These conventions were formalised in the Diana Dors picture Yield to the Night (J. Lee Thompson, 1956). In the book Images of Incarceration: Representations of Prison in Film and Television Drama (2004), Sean O’Sullivan and David Wilson note that films such as The Weak and the Wicked had an overt ‘social message and an educational purpose’ but ‘[t]heir portrayal of penal institutions was softened, with prison regimes being represented as strict rather than cruel. The critique of the institutions was that they were ineffective and that more progressive interventions were to be recommended’. The films therefore ‘reflect[ed] an ethos of welfare state optimism’ that was typical of the post-war period (40).

This aspect of the subgenre is also evident in Within These Walls. The series stars Googie Withers as Faye Boswell, the newly-employed Governor of Stone Prison. In the very first episodes, Boswell is established as an outsider to the penal system, commenting to another member of staff that ‘I’m well aware that many people don’t think that my experience in approved schools is sufficient qualification for this kind of security of prison’. However, being new to the prison system means that Boswell has not yet become desensitised to its injustices and, unlike the other guards, is capable of expressing shock when, for example, a sixteen year old girl is incarcerated in Stone Park in episode five, ‘Prisoner By Marriage’) or when a mentally ill inmate is housed in the general population (in episode seven, ‘One Step Forward, Two Steps Back’). Boswell therefore acts as a figure of identification for the audience, mediating the viewers’ shock at the workings of the prison and the prejudices of both the guards and the prisoners. As the series progresses, both Boswell and the viewer are educated in the running of the prison. At the beginning of the first series, Faye Boswell is clearly a ‘new broom’ who is intent on sweeping an element of compassion (and what we’d now call ‘tough love’) into the prison service. For Boswell, the prison system is about rehabilitation rather than restitution: ‘You come here as punishment, not for punishment’, she tells one of the prisoners. Boswell’s more liberal approach to the treatment of the prisoners in her care is placed in direct conflict with the values of the ‘old guard’, including Boswell’s deputy, Mrs Armitage (Mona Bruce); in the first episode, Boswell is reminded by a colleague that ‘You’ve brought a new, enlightened approach, which I believe is well needed; but if I may say so, older officers like Mrs Armitage are yet to be convinced of its value’. Nevertheless, Boswell’s good intentions are often frustrated, and as in the 1950s cinematic representations of life in women’s prisons the institution of the prison is shown as being ‘strict rather than cruel’, with an emphasis on a critique of ‘ineffective’ methods that are ingrained in the management of the prison. The audience is encouraged to sympathise with Boswell and her ‘more progressive interventions’, although her methods are often tested by both Boswell’s colleagues and the prisoners themselves. (Boswell is also occasionally painted as an idealist; when her student son reminds her that it costs more to feed a prison dog than a prisoner, Boswell raises this fact at work and is met with the simple declaration that ‘students do tend to overlook practical economics’.) In the first episode, Boswell fields accusations of prejudicial and brutal treatment towards an inmate (‘Whatever offence an inmate may be accused of, she is treated strictly according to how she behaves in this prison’, she tells an inquiring solicitor). This event leads to a visit by an MP, Victor Harkin, who reminds her of the importance of public relations which, it is suggested, are in some quarters valued over and above issues of rehabilitation or ‘fairness’ in treatment of the prisoners: reminding Boswell that the case is a ‘potentially very explosive situation’, the MP tells her that ‘It is a case in which justice must not only be done, but be seen to be done’. Later, it is shown that the prisoners understand this fact as much as the guards: the ‘Kyle woman’, as Boswell’s husband refers to her, is revealed to be trying to garner public sympathy before her trial starts and, to do this, has been inflicting injuries upon herself and blaming them on the prison staff.

Many prison narratives draw parallels between the lives of the prisoners and their guards, reinforcing the ways in which prison acts as a distillation of wider social issues, especially the impossibility of autonomous or ‘free’ action in a society that is riddled with bureaucracy. For example, Oz depicts a prison in which both the guards and the prisoners are both the subjects and the objects of prison brutality and degradation. Both guards and prisoners are under constant surveillance and monitoring, and as a consequence neither group is entirely ‘free’: both guards and prisoners transgress the established guidelines for behaviour (out of self-interest and, occasionally, necessity) and face punishment if they are ‘found out’. The roles of guard and prisoner are therefore effectively interchangeable. More closer to home, in Clement and La Frenais’ Porridge Fletcher (Ronnie Barker) often reminds Prison Officers Barrowclough (Brian Wilde) and MacKay (Fulton MacKay) that both the prison staff and the prisoners are effectively equal, as both groups have their behaviour restricted and limited to the walls of Slade Prison and both groups are under surveillance from ‘higher ups’: the prisoners are under surveillance by the guards, and the guards are under surveillance from the well-meaning but bumbling prison governor. In Within These Walls, the staff are similarly constrained by bureaucracy and, from the first episode onwards, seem to be under near-constant surveillance by politicians, lawyers and, especially, the media. The suggestion that the staff are as imprisoned as the prisoners is reinforced visually by the relative lack of scenes showing Boswell and her staff outside the prison environment. (However, the first episode notably ends with Boswell being greeted at the prison gates by her husband, who gives her a broad smile before offering to drive her home.)

As in many prison narratives, the conflicts between the prisoners are mirrored in the conflicts between the guards. Boswell finds her antagonist in Armitage: the two women have oppositional views on how to treat the prisoners. As in many British prison dramas such as The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (Tony Richardson, 1962), which uses its borstal setting as a metaphor for class conflict, the conflict between Boswell and Armitage is essentially class-based. The producers go to great lengths to depict Boswell’s home life as sturdily middle-class, whilst Armitage has a ‘rough edge’ to her character and her working-class roots are stereotypically signified in her fairly strong regional accent. However, as O’Sullivan and Wilson note that The Weak and the Wicked offers ‘a possibility for cross-class sisterhood’, Within These Walls suggests that cross-class co-operation is the best way to achieve one’s goals (op cit: 40). For Sue Harper and Vincent Porter (2007), films such as The Weak and the Wicked suggested that women are bound together by their gender, ‘not their social background’ (80). Thrown together into a tough situation, Boswell and Armitage similarly learn the value of working together, as many of the prisoners also learn the value of overcoming prejudices based on differences such as social class and race. Episode Breakdown: Disc One: 1. ‘A Cause for Concern’ 2. ‘Lesson Number One’ 3. ‘The Walls Came Tumbling Down’ 4. ‘In Her Own Right’ Disc Two: 5. ‘Prisoner by Marriage’ 6. ‘The Group’ 7. ‘One Step Forward, Two Steps Back’ Disc Three: 8. ‘Failing to Report’ 9. ‘Tea on St Pancras Station’ 10. ‘Guessing Game’ Disc Four: 11. ‘When the Bough Breaks’ 12. ‘Labour of Love’ 13. ‘A Sense of Duty’ Extras (on disc four): Text biography of Googie Withers 'Series Background' (text)

Video

As with many British television series of this era, Within These Walls was shot on a mixture of videotape (for in-studio footage) and film (for footage shot on location). Network’s DVDs contain a very clean and satisfying presentation of this first series of Within These Walls. The episodes are presented in their original broadcast screen ratio of 4:3.

Audio

Audio is presented in the form of a two-channel monophonic track. This is clear and problem-free. There are no subtitles.

Extras

Disc four includes a text biography of Googie Withers. Also included on disc four is a series background (text only).

Overall

According to the text series background included on disc four of Network’s release of the first series of Within These Walls, the success of the series in Australia led to the development of the long-running Australian prison-set series Prisoner: Cell Block H. As with many British post-war prison narratives, Within These Walls is issue-led; each episode has an overriding and socially-relevant major theme, from the issue of racial prejudice to the ways in which mentally ill prisoners are cared for. As a consequence, Within These Walls is an engaging and often thought-provoking series, far more so than many of its imitators (such as Prisoner: Cell Block H and Bad Girls) which, despite their cult reputations, tend towards the genre of soap opera due to their character-led nature. In contrast with these other series, Within These Walls is a more socially-minded drama, with its focus largely on the prison staff (rather than the inmates) and their battles with the internal politics of the prison system. Network have plans to release the second series on DVD. Hopefully they will distribute series three to five too, as it will be interesting to see how (and if) Boswell’s attitudes towards the penal system change and develop prior to the departure of the character in series four, in which she was replaced by a new governor named Helen Forrester (Katharine Blake). References/Further reading: Alber, Jan, 2007: Narrating the Prison. University of Michigan Press Brown, Mary Ellen (ed), 1990: Television and Women’s Culture. London: SAGE Publications Chibnall, Steve, 2000: J. Lee Thompson. Manchester University Press Hallam, Julia, 2005: Lynda La Plante. Manchester University Press Harper, Sue & Porter, Vincent, 2007: British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press Mason, Paul, 2006: Captured by the Media: Prison Discourse in Popular Culture. University of Michigan Press Mayne, Judith, 2000: Framed: Lesbians, Feminists, and Media Culture. University of Minnesota Press O’Sullivan, Sean & Wilson, David, 2004: Images of Incarceration: Representations of Prison in Film and Television Drama. Hampshire: Waterside Press Rapping, Elayne, 2003: Law and Justice as Seen on TV. New York University Press The Cinema Show: ‘In the Can: The Prison Movie’ (BBC, 2007) For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|