|

|

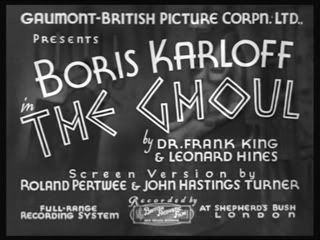

Ghoul (The)

R2 - United Kingdom - Network Review written by and copyright: Paul Lewis (20th February 2009). |

|

The Film

Based on the same Frank King novel as the Sid James and Kenneth Connors-starring horror parody What a Carve Up! (Pat Jackson, 1961), The Ghoul (T. Hayes Hunter, 1933) marked horror icon Boris Karloff’s return to Britain. After his success in Universal’s horror films Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931) and The Mummy (Karl Freund, 1932), Karloff was attached to James Whale’s 1933 adaptation of H. G. Wells’ The Invisible Man. However, according to Scott Allen Nollen’s book Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Stage, Screen, Radio, Television and Recording Work (1991), Karloff became alienated with Hollywood due a combination of behind-the-scenes politics and the financial impact of the Depression on American film studios—which led to Karloff being railroaded into a position where Universal would only allow him to work if he conceded to a significant reduction in pay (83). In response, Karloff returned to the UK and starred in The Ghoul, which was produced for British-Gaumont and directed by an American, T. Hayes Hunter. As the film opens, an Egyptian named Mahmoud (D. A. Clarke-Smith) stalks a man named Dragore (Harold Huth). Dragore enters his lodgings. Ringing Dragore’s doorbell, Mahmoud is met by a middle-aged woman (who comically tells him ‘We don’t want to buy no lino nor nothing'). Discovering that Mahmoud is there to see Dragore, the woman allows him to enter the building.  Mahmoud reveals to Dragore that he has come to claim the Eternal Light, a jewel that has been taken from a tomb. From Dragore, Mahmoud discovers that the Eternal Light has been sold to Professor Henry Morlant (Boris Karloff), who Mahmoud declares to be ‘That robber of the dead’. Morlant is dying and it seems that he has ‘gone native’: he believes that the Eternal Light will guarantee him passage to the afterlife, that it will in Mahmoud’s words ‘open for him the gates of paradise’. With the collaboration of his butler Laing (Ernest Thesiger), Morlant has made plans for a ritual burial, with ‘the figure Anubis [placed] at the west of the chamber’. The butler refers to the figure of Anubis as a ‘heathen image’ but respects his master’s wishes, although he declares ‘I’m afraid for you’. With the aid of a bandage, the Eternal Light will be sealed into the palm of Morlant’s hand. On the full moon, Morlant will rise from the dead and place the Eternal Light in the statue of Anubis, thus allowing him access to the ‘gates of paradise’. However, Morlant warns Laing that if the Eternal Light is removed from his hand Morlant ‘will come back to kill’. After Morlant’s death, his mercenary nephew Ralph (Anthony Bushell) visits Morlant’s solicitor Broughton (Cedric Hardwicke) and is angered to learn that his uncle has spent most of his fortune. Ralph vows to visit Morlant’s home. Meanwhile, Morlant’s niece Betty Harlon (Dorothy Hyson) receives a letter telling her that her uncle has left her ‘a fortune’. She also vows to visit Morlant’s home, but on the way her purse is snatched by a mystery man. Not long after, Ralph arrives. ‘You would go and get yourself into some kind of mix-up’, he tells her; ‘You would arrive when it’s all over’, she berates him.  It is revealed that following a family feud orchestrated by their uncle, the immediate families of Ralph and Betty no longer speak to each other. Betty reveals to Ralph that the letter she received urged her to come to Morlant’s home, whilst Ralph declares that ‘Broughton was doing everything he could to keep me from there’. Shortly after Betty and Ralph arrive at their uncle’s home, Dragore arrives and declares his interest in visiting Morlant’s tomb, clearly intending to retrieve the Eternal Light. Dragore responds badly to the suggestion that Morlant’s beliefs were an example of paganism: ‘The Egyptians were not pagans, sir’. The group are shocked to discover that the talisman has been removed from Morlant’s hand and the dead man does indeed return to life, terrorising his visitors and killing them one-by-one. The Ghoul was an attempt to tap into the success of the Universal horror films; as Kim Newman notes in the commentary on this DVD release, The Ghoul deviates quite drastically from the Frank King novel on which it is based. This is most noticeable in the addition of what Newman refers to as ‘Egyptology business’ revolving around Karloff’s character’s obsession with Anubis, the Egyptian funerary god. These references to Egyptology were presumably added to (in Newman’s words) ‘beef up the role for Karloff’ and capitalise on his role in The Mummy. However, The Ghoul is in many other ways stereotypically British, a mixture of the horror film and the mystery-thriller along the lines of James Whale’s The Old Dark House (1932), which also starred Karloff and Thesiger. The Ghoul employed the talents of a number of German émigrés, including art director Alfred Junge and cameraman Günther Krampf. According to Paul Moody’s entry on the film for the BFI’s ScreenOnline website, Junge and Krampf’s ‘excessive demands’ led to the film coming in £10,000 over budget (at £40,000) but resulted in ‘visual achievements that are the film’s major point of interest today’ (np). In The Unknown 1930s: An Alternative History of the British Cinema, 1929-1939 (2001), Jeffrey Richards asserts that the visual style of the picture—with its use of oblique angles, low-key lighting and symbolic deep shadows—was ‘strongly influenced by the cinema of German Expressionism’ (88). This is evident from the outset, during the sequence in which Mahmoud stalks Dragore; in this sequence, the filmmakers signify threat and danger through an expressionistic use of deep, rich shadows (in which Mahmoud hides) and high angle shots (such as the high angle shot which depicts Dragore ascending the stairs to his lodgings). Thus Richards states that ‘[t]here is a strong case to argue that The Ghoul can be placed within a movement in British cinema of the time which sought to differentiate itself from Hollywood films by emphasising aspects of “European” style’ (88). Consequently, The Ghoul has been seen as an attempt to develop a distinct identity for the British horror film whilst at the same time imitating the success of the American horror films that were popular during the period.  For many years, The Ghoul was considered a ‘lost’ film and acquired what could best be referred to as an inflated reputation, until it resurfaced in 1969 when a highly worn nitrate print was discovered in Czechoslovakia. When this print, complete with Czechoslovakian subtitles (or sometimes shown in a version that was heavily cropped in order to remove the subtitles), was screened in the 1970s ‘many of those who anticipated a rediscovered masterpiece were somewhat disappointed’ (Nollen, 1991: 84). In Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties (1997), Tom Johnson notes that the film’s rediscovery was met with ‘great dismay’ (89). Johnson concedes that the film has ‘historical significance’ but, somewhat melodramatically, states that ‘despite [this] it is practically unwatchable’ (ibid.). Karloff is given relatively little screen time, and as Kim Newman notes in the DVD commentary Karloff is given hardly any lines of dialogue, meaning that throughout the film his distinctive voice is vastly underused. The film is also sometimes criticised for its uneven tone. The opening third of the film (which establishes the quest for the Eternal Light and Morlant’s obsession with Egyptian funerary rites) is effective and well-shot, but the middle portion of the film is bogged down with static scenes depicting the visitors to Morlant’s home. Then, with the rebirth of Morlant, the film acquires a new sense of energy; Scott Allen Nollen suggests that ‘Hunter’s direction is lackluster in the non-Karloff sequences [but] his style improves immeasurably when Karloff is featured’ (op cit.: 85).   The Czech print seems to be no longer in circulation, replaced by much better prints; and as Newman and Jones note in the DVD commentary, these prints have led some people to reassess their feelings towards the film, allowing viewers to better appreciate the film’s visual design. The film is certainly visually impressive, but as noted above it is uneven and somewhat unsatisfying on a dramatic level, with the narrative coming to a halt midway through the picture; the film also underuses Karloff, although his return from the dead (as the titular ghoul) is hugely effective.

Video

The film runs for 77:04 minutes (PAL) and seems to be the longest version in existence, although on the commentary track Newman and Jones reflect on the fact that the film may have existed in several different edits. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 1.33:1. The monochrome image is crisp and clean and shows off the film’s expressionistic low-key lighting.

Audio

Audio is presented via a two-channel monophonic track. This is clear; dialogue is always audible. There are no subtitles.

Extras

Extras include: - An audio commentary by Kim Newman and Stephen Jones. In their lively and informative commentary track, Jones and Newman discuss issues such as the film’s long-held status as a ‘lost’ film and its availability, since the 1970s, via the worn Czechoslovakian print. Jones notes that ‘This new print that we’re watching here certainly led to a reassessment of the film over the past ten years’. Newman and Jones also discuss the film’s relationship with the US horror films of the period, and Newman suggests that The Ghoul was an attempt at ‘reclaiming the horror genre from America’ after British directors and stars had been ‘poached’ by Hollywood. Newman discusses the film’s basis in the novel by Frank King, which Newman describes as ‘an Edgar Wallace “knock-off”’ which ‘starts off’ as a novel about ‘organised crime’ but then becomes a horror story. - A stills gallery is also included.

Overall

The Ghoul is an interesting picture; it certainly has its moments, although it’s very uneven in tone. Visually the film is very engaging, but on a narrative level the film has its problems, with the central portion of the narrative feeling ‘padded out’. The film also lacks an engaging protagonist. As Kim Newman notes in the DVD commentary, ‘[i]t’s one of those plots where everybody’s guilty; there’s nobody good here’. As such, viewers may find it difficult to find a character with whom they empathise. The film also underuses Karloff, who the credits suggest is the star of the picture; this must have been very frustrating for audiences in the 1930s, who may have been lured to the picture with the promise of seeing Karloff in a leading role following his success in the Universal horror pictures.

All in all, The Ghoul is certainly worth a look for fans of classic horror films, although for newcomers to Karloff’s cinema, the British horror film or 1930s horror cinema in general, there are much better places to start. Newman and Jones’ commentary track is interesting and informative; for fans of the film, the commentary alone makes this DVD a worthwhile purchase. References: Johnson, Tom, 1997: Censored Screams: The British Ban on Hollywood Horror in the Thirties. London: McFarland Moody, Paul, 2003: ‘The Ghoul’ (capsule review). ScreenOnline. [Online.] http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/444009/index.html Nollen, Scott Allen, 1991: Boris Karloff: A Critical Account of His Stage, Screen, Radio, Television and Recording Work. London: McFarland Richards, Jeffrey, 2001: The Unknown 1930s: An Alternative History of the British Cinema, 1929-1939. London: I. B. Tauris For more information, please visit the homepage of Network DVD.

|

|||||

|